On ground cool with concrete tiles, a woman carefully smoothed a turquoise and burnt orange printed sheet in front of her. She tenderly unfolded three white baby onesies and laid them on the fabric. Kneeling before her simple shrine she clutched her stomach, raised her eyes to heaven and started her kinesthetic prayer. Thousands of fellow congregants danced and shook around her. A woman sprawled on the ground crying; a man walked in place with his eyes closed, mouth racing with determination.

From his lectern at the front of this cavernous auditorium, Pastor Enoch Adejare Adeboye, a tall smiling man with plum cheeks, said, "You can pray sitting, you can pray lying down, you can pray standing, any way you want. Begin to talk to the Almighty God." He'd titled the conversational sermon "God will make you laugh." The promises and prophecies conveyed to the gathered faithful were mostly of miraculous fertility.

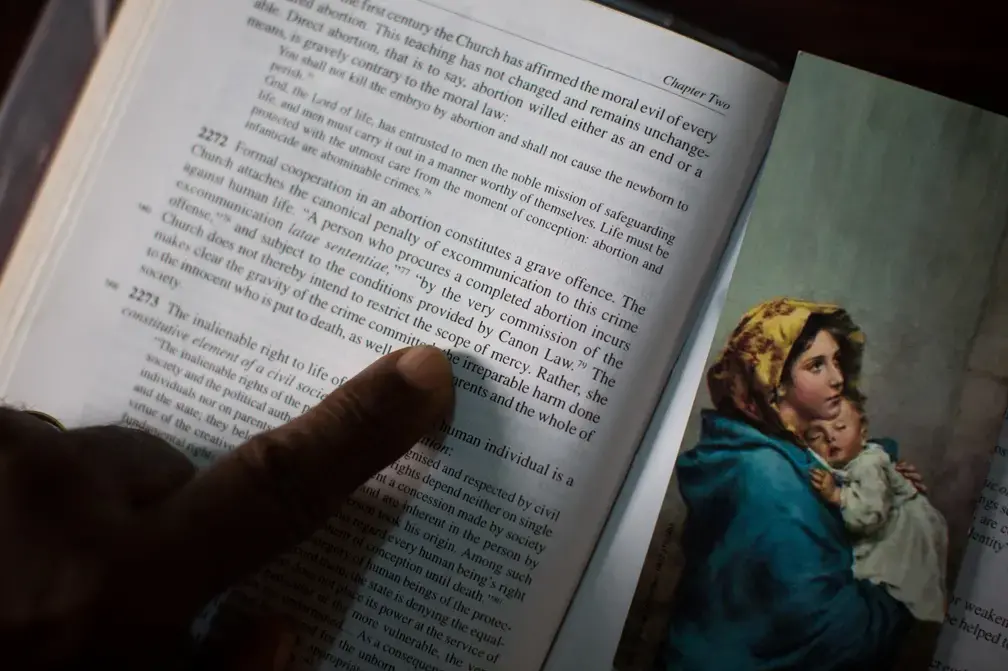

Religion is big in Lagos. Not just in size, not just in sound, nor in the omnipresence of reminders on billboards, bookmarks, pins and bumper stickers. It is big in the consciences of Nigerians, in the public understanding of morality, and in political debates. Abortion is legal here only to save the life of a mother, and in all cases, taboo. Religious groups consistently lobby the government to keep the restrictions in place.

But despite the restrictions, at least 760,000 abortions happen every year, with complications killing between 3,000 and 34,000 women annually, according to estimates by the Guttmacher institute and the government. Women go to pharmacists, herbalists or expensive qualified doctors for a wide range of clandestine procedures. Often the cheapest abortions are the most dangerous.

"Here, people love babies. They want to make children," Ngozi Iwere, an elegant and soft-spoken women's rights activist in Lagos, said. "You can't tell people it's a fetus. You are pregnant and you will have a baby. The debate here is 'is it morally right for a woman to have an abortion?'" Iwere was one of four founders of the Campaign Against Unwanted Pregnancy, in the early 1990s. The initial goal of the group was to convince people to publicly utter the word abortion without having media and political backlash "erupt."

Pastor Adeboye's service, and the fervent prayers of his congregants, demonstrates the beliefs and social pressures that define abortion as a social anathema. He recounted anecdote after anecdote of relief from barrenness and the glory of God through children.

"The Lord says there is a lady here who will find a sudden movement in your belly, and he said the demon affecting the seed of your husband has been dealt with," he said, as a roar built from the crowd and echoed through the rafters.

The church, claimed to be the world's largest, is the home of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, a Nigerian Pentecostal denomination that has grown exponentially under the watch of Pastor Adeboye, nicknamed Daddy G.O. for General Overseer. The auditorium at Redemption Camp, outside of Lagos, can house one million worshippers. That night it was half full, but the church is currently constructing a new one that will be three kilometers square.

One of the primary fears women have around abortion is of long-term impacts on fertility. The fears are grounded. Bunmi Aiyenuro, a 23-year-old hairdresser, had seven abortions at the insistence of her boyfriend, but when he decided he was ready to have a family she miscarried twice and he left her. She now attends church services and begs God to forgive her for her sins.

Aiyenuro lives in Badia, a bustling slum crowding the railroad tracks. Her fellow denizen, Tope, had three abortions five years ago. She asked to be identified by her first name out of fear of stigma. She calls her abortions "the sin I committed against God."

Now she dons a regal white gown to spend hours in church every Sunday, dancing and praying. She regrets her abortions and says she wouldn't do the same now. "Now I want to live as a married woman, have the baby," she said. "I pray to God, I am waiting for my time, for my man."

¤

One Wednesday morning at the National Headquarters of the Celestial Church of Christ in the Makoko neighborhood in Lagos, dozens of women lay on the concrete floor in meditation. A handful of men reclined across the aisle; the church separates the congregation by gender.

This is the Seeker Service, a weekly occasion for Celestiants, as adherents are called, to "gather to seek God's face for mercy and special favors," explained Afis Kiki, the Shepherd in Charge, or head pastor at the parish.

The women were dressed head to toe in white, as is traditional in this six decade-old church, founded in Benin. "People's major focus is pregnancy," said Afis. Fertility is "not the priority of the service, it's just one of those things," he said. But given the number of symbolic candles, coconuts, bananas and water bottles splayed next to the women, it was clearly a very important thing.

For Celestiants, along with many other denominations, women play an essential role as the bearers of the next generation. "Family planning is according to divine order," Afis said, "Go forth and multiply, that is our family planning." As for abortion? "No no no, it is not allowed, it is an abomination."

Religious beliefs influence women and providers to be discrete about abortion. Few people will admit to procuring or providing the procedure out of internal guilt and public shame. But religion also influences the policies around abortion.

"A big barrier is that historically the government has never wanted to stand up to religious groups," said Richard Boustred, country director at Marie Stopes International, a women's health organization. "The view is that a child is God's gift and you don't get to decide when God gives you a gift."

The vast majority of Nigeria's Christians and Muslims believe abortion is wrong, according to the Pew Research Center. So political leaders have little motivation to loosen the legal restrictions around abortion, even as they recognize the public health costs of keeping abortion underground.

"We all know that septic abortion precisely has a lot of impacts on maternal mortality in Nigeria," said Dr. Bose Adeniron, head of the reproductive health division at the Federal Ministry of Health. But she said there is no plan to change the policy now.

"It's the cultural setting […] We all know there is a lot of stigma attached to it. A woman gets pregnant, has an abortion. That means that she is engaging promiscuous activities [...] if a woman continues to do that, eventually when she gets married legally, she may not be able to have children," Adeniron explained, "people don't really want to encourage people to have abortion."

But as the numbers show, the stigma and the legal restrictions are not keeping women from finding a way to terminate unwanted pregnancies. They are only pushing the procedures out of the formal sphere and into a dangerous and shadowy market.

"If you don't recognize it, everyone's going to do it anyway, but it's going to be completely unregulated," Boustred of MSI said, and "because it's unregulated some really nasty things happen."