- Rio de Janeiro holds a special place in Brazil’s history, but many of its residents are unaware of the city’s Indigenous heritage — from the names of iconic places like Ipanema and Maracanã, to the Indigenous slave labor that built some of its most recognizable structures.

- Nearly 7,000 Indigenous people live in Rio, the fourth-biggest population among Brazilian cities; a unique interactive map by Mongabay shows how they’re spread across the city, as well as their living conditions and ethnic groups.

- Despite their presence, and Rio’s famed diversity and laidback culture, Indigenous people in the city continue to face prejudice and a “silencing” of their traditions and culture that they attribute to centuries of efforts to erase them and make them invisible.

- But Indigenous people are pushing back, agitating to get their rights on the political agenda, and working through academia to unearth the Indigenous history of the city that has long been hidden.

RIO DE JANEIRO — Maracanã, Ipanema, the Lapa Arches, the Church of Our Lady of Glory of Outeiro ... Millions of the visitors who flock to Brazil’s most famous city every year will be familiar with these places and with local expressions like carioca, the word for a native of Rio de Janeiro. But what most visitors, and even cariocas, don’t know is that all these places (and the word carioca) have an Indigenous root — whether through the slave labor that built them or from the Indigenous lands that they displaced.

“Many people pass by Arcos da Lapa [the Lapa Arches] but they don’t imagine that that monument that is now a heritage, a symbol of the city of Rio de Janeiro, was built by Indigenous slave labor,” says historian Ana Paula da Silva, who has a Ph.D. in social memory and is a researcher at the Program of Studies of Indigenous Peoples (Pro Índio) at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ).

The arches, in the bohemian Lapa neighborhood of old Rio, were built in the 17th and 18th centuries to support the Carioca aqueduct bringing water to the city center from the Carioca River. Today, Lapa is the beating heart of the city’s nightlife, and instead of water the aqueduct ferries a popular cable car to the uphill neighborhood of Santa Teresa — leaving those who toiled and died to build it largely forgotten, da Silva says.

“Today we don’t have that memory, [or that] history in books, in the media, nobody tells this story,” she says. “There isn’t [even] any sign saying that [in the monument].”

Another “hidden” aspect of the city’s history, according to da Silva, lies beneath the Church of Our Lady of Glory of Outeiro. Perched atop Glória Hill, a 10 minute-drive from the Lapa Arches and visible from many parts of the city, it’s popularly known as Igreja da Glória or Outeiro da Glória. It was built on Tupinambá Indigenous territory disputed by French and Portuguese colonizers and Indigenous peoples during the reconquest battles of the 16th century. According to reports from the French expedition, at the foot of the current church sat a Tupinambá village called Kariók or Karióg, the name that most likely gave rise to the word carioca. Da Silva says the construction of the church was also a symbol of the Catholic Church’s triumph after the battle, literally imposing Catholicism on the native people. The church became one of the most beloved places frequented by the Portuguese royal family after they moved the seat of their empire to Rio de Janeiro in the early 19th century.

Countless names and expressions that are part of Rio’s daily life derive from the Tupinambá language (also called old Tupi or simply Tupi), but most people are unaware of that, da Silva says. Ipanema, the beach neighborhood that gained international prominence through the 1960s jazz hit “The Girl from Ipanema” by Brazilian singer and composer Antônio Carlos “Tom” Jobim, means “bad water” in the Tupinambá language. The Maracanã neighborhood, home to the iconic stadium, takes its name from a type of macaw, whose meaning is similar to a rattle, after the sound it makes; there’s a Maracanã River. Carioca itself refers to the name of a river (it passes under the Lapa Arches) and a village, which, according to some historians, refers to the dwelling of the Indigenous Carijó people; others interpreted it as a white man’s house or a house with running water or a stream coming out of the forest. Da Silva says the meanings of these names may have varied over time; there are an estimated 40,000 Indigenous entries in the Brazilian dictionary.

Many Rio visitors and residents alike are also unaware of the many Indigenous habits that today form part of the Brazilian lifestyle, da Silva says, including taking a shower every day — the Portuguese colonizers weren’t used to that when they arrived in Brazil, she says — or sleeping in hammocks, or having a diverse diet, including cassava.

“All this because of our education, because of our history that deconstructed, that silenced and removed the Indigenous [people], placed the Indigenous in an underprivileged place actually, didn’t include the Indigenous as part of our history, of our society, so this is very complicated,” she says. “People have become naturalized not to see Indigenous peoples.”

Da Silva spoke to Mongabay outside the Paço Imperial (Imperial Palace) in downtown Rio — another iconic structure built with Indigenous slave labor.

“The renovations of the Paço Imperial behind us, the renovations of the Passeio Público [park] also used Indigenous enslaved workforce,” da Silva says, adding “there was even a dispute between the Navy, the Rio de Janeiro City Council [and] the police for this manpower,” pointing to an extensive documentation in the city’s archives with all these records.

At nearly 7,000, Rio’s Indigenous population is the fourth-biggest of any Brazilian city in absolute numbers, according to the country’s 2010 census, the latest available. (The next census is due in 2022.) But this Indigenous presence is “diluted” among a total population of 7 million (less than 0.1% of the total), says João Pacheco de Oliveira, a professor and curator of the ethnographic collections at the National Museum and member of the Science and Culture Forum of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

“The presence of Indigenous peoples in cities is something very important. It just needs to be understood because it’s something of a different nature,” Oliveira says. “In the city of Rio de Janeiro, it is diluted. The same thing happens in several other [state] capitals … Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Brasília have Indigenous from all over Brazil.”

He says Indigenous people usually come to big cities like Rio for the economic and job opportunities, but few groups are really able to forge a community, as they’re distributed throughout several areas. It’s different from the cities in Brazil’s north and northeast regions, where entire Indigenous neighborhoods have been established.

A unique interactive map built by Mongabay shows how Indigenous people are spread all over Rio. It also shows their living conditions and their ethnic groups.

The Rio de Janeiro neighborhood with the highest number of Indigenous people is Campo Grande, in the western suburbs, 55 kilometers (34 miles) from the city center. In 2010 it was home to 373 Indigenous people, accounting for 0.11% of the population. Copacabana, the city’s most famous neighborhood, was home to 222 Indigenous people — the fourth-largest population among all the Rio neighborhoods but representing just 0.15% of the total — mostly from the Tupiniquim, Guarani and Terena groups, along with other ethnicities. There were also 123 Indigenous residents in the historical Santa Teresa neighborhood, and 42 in Ipanema and 30 in Leblon, both hugely popular areas with tourists for their beaches.

‘More power to say who you are than you’

The Indigenous ethnic diversity in Rio de Janeiro is very rich. The 2010 census lists 127 Indigenous ethnic groups in Rio who speak 26 languages. The Guarani people top the list with 261 of the total, followed by the Tupiniquim (171), Guarani Kaiowá (144) and Tupinambá (136) ethnic groups (see infographic below). The presence of Indigenous people from other countries is also significant (152), highlighting the appeal to foreigners and Indigenous people from all over the country of the “marvelous city.”

The 2010 census was the first in Brazil’s history to record this diversity, because it was the first to identify the Indigenous presence in reserves, rural areas and urban areas across the whole of Brazil. The census even recorded the presence of people from the Puri ethnic group, which had previously been considered extinct; 50 of them lived in Rio in 2010, the census showed. The true number of ethnic groups in the city is likely to be higher, as 4,247 Indigenous respondents (63% of the total) said they didn’t know the ethnic group they belong to, while the ethnicity of 351 Indigenous respondents was classified as poorly defined, and that of 386 others was undetermined or undeclared, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

But a decade later, self-declaring as Indigenous is still “painful,” interviewees told Mongabay, citing ingrained prejudice among the non-native cariocas and in Brazilian society as a whole.

Born in Rio, school history teacher Marize Vieira de Oliveira Guarani, 62, only recognized herself as Indigenous 16 years ago, despite having a Guarani grandmother. “I always knew about my [Indigenous] grandmother. But I didn’t declare myself Indigenous, I didn’t self-declare anything. Why? [Because] it didn’t even exist [in the census] the Indigenous categories for cities,” she says. The option to self-declare as Indigenous appeared in the 1991 and 2000 censuses, but was restricted to a small sample of the population; only in the 2010 census was it made available to all Brazilian citizens.

Marize Guarani says she realized the Indigenous culture “persists within the family,” regardless of the fact that she lived in the city, when she served as director of gender, anti-racism and sexual orientation at Rio’s teachers’ union. At the time, she says, the Black movement was urging Indigenous people to claim the right to self-declaration as Indigenous instead of pardo (brown). “I began to realize that my grandmothers could not be silenced.”

Because Marize Guarani also had a Black great-grandmother, she self-declared as Afro-Indigenous in 2005, during the first National Conference on the Promotion of Racial Equality in Rio. As the only self-declared Indigenous woman in the conference, she says she was “scoffed at” and even called “supposed Indigenous.” In the schools where she worked, Marize Guarani recalls, she was called “Indigenous made in Paraguay” — “do Paraguai” being a common expression in Brazil for a knock-off item.

Even when she was pursuing her master’s degree in education, Marize Guarani says, a fellow teacher asked if she was “a real Indigenous.” As this teacher declared herself Black despite having honey-colored eyes and brunette skin, Marize Guarani says she answered: “But you were not born in Africa. You are also a descendant. So I want to know why you have the right to declare yourself Black and to me you give me the right to be nothing. Because for me, pardo is [the color of] paper.” She says her colleague was embarrassed and apologized, telling her she “had never looked at it that way.”

“[That’s] epistemic racism, institutional racism … it gives people more rights, more power to say who you are than you,” Marize Guarani says. “They can’t realize that this was so denied to us, until you feel a sense of belonging, it’s something very, very painful. Even more painful when you declare yourself.”

Marize Guarani was the first Indigenous person to enroll for a doctorate degree in education at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in neighboring Niterói city, through the quota system for Indigenous people. Before self-declaring as Indigenous, she says, she was involved with Indigenous movements in Rio, where she would refer to herself as a descendant of the Guarani people. But that changed, she recalls, when a Pataxó leader told her: “You said you’re a descendant. Whoever ‘descends’ is on the fence. There is no fight. You’re a warrior. So you can’t say you descend. You are.”

After self-declaring as Indigenous, she adopted the Indigenous name Pará Rete, which means “that which comes from the sacred.” Marize Guarani interprets it as “a warrior who fights and protects her people.” She was baptized by a Guarani shaman under the blessings of Nhanderu, the god of the Guarani people. “It’s a name that honors me. It honors my spirit, strengthens my spirit.” However, she says she didn’t add it to her official documents, given the onerous bureaucracy involved in legally changing her name.

Marize Guarani says she was always told she looked like “people from the north,” but didn’t understand why until she traveled to the Amazon region and encountered the region’s Indigenous residents. She also says that when she was a child, people would ask her mother whether she had painted her child’s hair black, because people didn’t believe it was naturally that black. She says the color of her hair recalls Iracema, the protagonist and title of a famous romance by the writer José de Alencar, whose hair was “blacker than the raven wing.”

When Brazil hosted the 2014 World Cup, Marize Guarani says, a waitress spoke Spanish with her and she didn’t understand why. When she told her she was Brazilian and “the most Brazilian because I’m Indigenous,” the waitress was very surprised, she recalls, saying she thought she was Colombian. “Do you understand what invisibility is? People identify us as other people” — not as Brazilian or Indigenous.

“The same diaspora that the African people suffered, when they came by force to Brazil and America, we suffer the same diaspora but within the [Brazilian] territory,” Marize Guarani says.

World Cup battle

It’s naturally more challenging to establish an Indigenous community in the big city than it is in a village, but Indigenous people always seek to be grouped together as “a protection mechanism for those who arrive first and bring their relatives behind,” says José Carlos Matos Pereira, a researcher at the Social Movements Memory Program and sociologist at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Matos, who has a postdoctoral degree in social anthropology, notes that the Indigenous presence in Rio de Janeiro is mostly in the city’s outskirts. Census data show that the highest concentration of Indigenous people is in Rio’s western region. The top three neighborhoods with the biggest Indigenous populations are Campo Grande, Santa Cruz and Bangu. The Indigenous presence in Rio’s urban areas is also significant in the so-called subnormal clusters, a term used by IBGE to classify irregular occupation of land owned by others — public or private — for housing purposes in urban areas lacking essential public services, like sewage. To most Brazilians and the world, subnormal clusters are better known as favelas.

According to the 2010 census, at least 850 Indigenous people (about 13% of the total) lived in Rio’s favelas. Rocinha, Brazil’s largest favela, located in southern Rio, was home to 60 Indigenous people — the highest number among the 183 favelas where IBGE recorded Indigenous residents. (The city has 763 favelas.) Vidigal, another famous favela in the south, between the tourist hotspots of Leblon and São Conrado, was home to 11 Indigenous people. But the real number of Indigenous people in favelas is higher, given that IBGE didn’t disclose the numbers in some favelas to preserve their identity, according to demographic criteria. That was the case with the Copacabana favelas of Morro do Cantagalo and Pavão-Pavãozinho, for example.

A spotlight of the Indigenous resistance in Rio is the so-called Aldeia Maracanã (Maracanã Village), a building just a few meters from the world-famous stadium in the city’s north. The building previously housed Rio’s Museu do Índio (Indigenous Museum) until the end of 1970s, when the entire ethnographic and Indigenous language collection was distributed between the new Indigenous Museum in the Botafogo neighborhood, the National Museum, and Brasília. Indigenous people say some of the archives were even burned and the building abandoned for many years.

In 2006, it was occupied by a group of Indigenous settlers who wanted to create a cultural center in the area. The occupation made international headlines in 2013 when the Rio de Janeiro state government sought to evict the group to build a parking lot for the World Cup the following year, triggering a land ownership legal battle that continues today.

The Aldeia Maracanã episode is a clear mirror of the struggle Indigenous people face in Rio, Matos says. “When they tried to remove the Indigenous people from there, Rio de Janeiro’s [state] environment secretary said: ‘Indigenous people belong in the Indigenous village.’ So what does that imply? It implies the denial of the presence of Indigenous people in the cities,” Matos says. “This denial shows, through our urban policies, the lack of policies targeting the Indigenous population. The majority of the city’s master plans, which are the municipal policies that will guide the urban policies, make very few mentions of Indigenous people.”

The difficulty in obtaining information about specific public policies for Indigenous people in urban areas was evident when Mongabay tried to find out if there were any in Rio. In a statement, City Hall said the state government is responsible for setting public policies for the Indigenous population, adding that “Indigenous communities are located in other municipalities in the state.”

In a statement, the Rio de Janeiro state government said Indigenous people are covered by a state law on quotas for places at state universities, which Rio state “was a pioneer in adopting.” UERJ set up a quota system for Indigenous people in 2003, following a previous model set up in 2001 for Black and pardo citizens, through self-declaration. At the time though, to enter the university through the quota system as Indigenous depends on validation by Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs, or community leaders to which the applicants belong, according to the UERJ website.

In a statement, the government’s social development and human rights office said it acts in response to Indigenous people’s demands in the state based on deliberations by the State Council for Indigenous Rights (CEDIND), created in 2018 to guarantee the rights of Indigenous people living in villages and in an urban context.

Last year, the council, which has Indigenous leaders, carried out five actions in response to the demands of the state’s Indigenous population. The government highlighted five actions for Indigenous populations carried out last year through the state; in the capital there was just one: food aid to Aldeia Maracanã and to Aldeia Vertical, an Indigenous housing project.

On Aldeia Maracanã, the state secretariat for culture and creative economy said it has maintained a dialogue with the Indigenous groups in the building “to seek a joint solution for the recovery of the property and the future development of activities that include history, culture and others contributions of Indigenous peoples,” without providing any detail regarding the legal battle over the site.

Over the years, there have been several cycles of occupation and eviction — and even imprisonment of Indigenous leaders — at Aldeia Maracanã, where today five families from seven ethnic groups live.

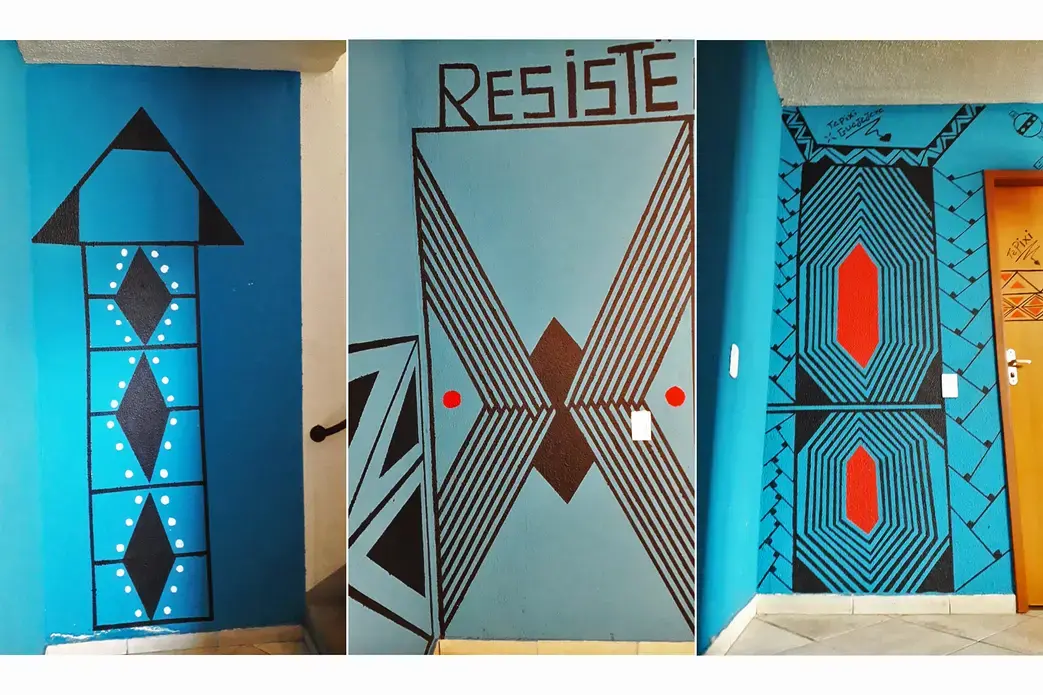

“They fluctuate a lot, because it’s not easy to survive here, without light, without water, without a sewage system. We only built this structure after the 2016 Olympic [Games],” Indigenous chief José Urutau Guajajara tells Mongabay at Aldeia Maracanã, in a big living room of the old ruined palace, with Indigenous paintings on the walls and the din of nearby traffic coming from outside.

José Guajajara was born in the village of Lagoa Comprida in northeastern Maranhão state. He has a master’s in linguistics from UFRJ and is doing a doctorate in linguistics at UERJ. He says he lives between Aldeia Maracanã and Complexo do Alemão, a group of favelas.

He says the Aldeia Maracanã struggle dates back to the late 1990s and early 2000s, when Indigenous people demanded space to accommodate the large number of Indigenous people living in urban centers, and to debate public policies pertinent to their context.

At Aldeia Maracanã, he teaches Indigenous languages of several trunks, mainly the languages from the Tupi trunk and from the Tupi-Guarani families. “With Aldeia Maracanã, our intention is to create a nano-territory, a university inside this territory, which is Indigenous land because this is a heritage that belongs to the federal government, to the Brazilian people,” José Guajajara says. “The Maracanã Village Indigenous University is this junction of Indigenous peoples, this union of languages and their native speakers.”

The old Museu do Índio was a milestone for Indigenous history in Rio de Janeiro. Founded in 1953 under the institutional guidance of anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro, it hosted important events, including discussions for the establishment of the Xingu Indigenous Park, Brazil’s first Indigenous reserve, created as a national park in 1961 in midwestern Mato Grosso state. It also sheltered Indigenous groups from other parts of Brazil during several events, including the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, held 20 years after the landmark Rio Earth Summit.

The legal battle over Aldeia Maracanã is complex, involving the sale of a 14,300-square-meter (154,000-square-foot) property (of which the old Museu do Índio accounts for 1,500 m2, or 16,000 ft2) from the federal government to the state of Rio de Janeiro in 2012. There followed negotiations for the concession of the area for the renovation of the Maracanã stadium for the 2013 Confederation Cup and 2014 World Cup. The bid to develop the concession was won by a consortium led by Odebrecht, the Brazilian engineering behemoth at the center of the Lava Jato corruption scandal that led the company to declare bankruptcy, saw its CEO jailed, and even landed former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in jail. The Maracanã concession is currently managed by Rio soccer teams Flamengo and Fluminense.

The dispute over the property has even caused a split among Indigenous groups. After a negotiation with the Rio state government in 2013, the settlers left the area and the building was listed by the Rio city and state governments in 2013, under the promise that the space would be renovated and transformed into a cultural center, according to Indigenous people who previously occupied the area and are now grouped under the Maracanã Village Indigenous Association.

Dissatisfied with the agreement, a group led by José Guajajara, named Aldeia Resiste (Village Resists), occupied the building again in 2016, calling the other group “traitors” and filing a lawsuit demanding the entire area of 14,300 m2 be demarcated as an Indigenous reserve for the creation of an Indigenous university. They have since faced constant threats of eviction, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, José Guajajara says.

“We are a university,” he says. “We [told the government we] don’t want the cultural center, because the cultural center doesn’t fit a university. And within a university, which is within a micro territory, there are several cultural centers, several cultural points, several projects, but a cultural center does not fit a university … and the resistance will remain here.”

Part of the group who accepted the government proposal to vacate Aldeia Maracanã were moved to a building with 20 apartments dedicated to Indigenous families in the Estácio neighborhood in central Rio. The building was part of the Lula government’s accessible-housing program launched in 2009, called Minha Casa Minha Vida (My Home, My Life); this particular building is now known as Aldeia Vertical (Vertical Village).

History and philosophy teacher Sandra Benites Guarani Nhandeva is from Porto Lindo village in the town of Japorã, in midwestern Mato Grosso do Sul state. She has lived at Aldeia Vertical since 2016, paying regular mortgage and building fees. She has a master’s degree in social anthropology from UFRJ’s National Museum and is now pursuing her doctorate in social anthropology there. She is also assistant curator of Brazilian art at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP).

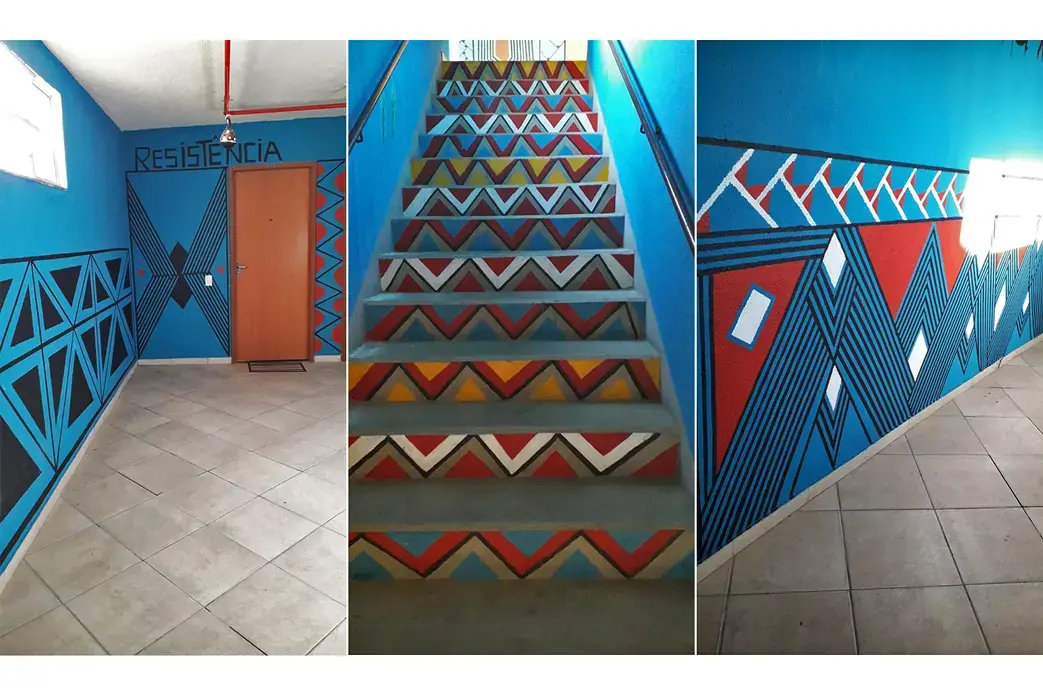

She says the Indigenous residents are always “fighting” to make the place look like home and feel unique within the other buildings in the cluster, with Indigenous graphics on the walls and stairs, a mini library at the entrance, and a community vegetable garden “gradually changing the building.”

But they face limitations in how they can practice their traditional rituals, she says. “We have our dance, or songs. But this is impossible [to practice here] because it’s a condominium, there are other people around, and we have to respect the norms of that condominium, that building. We have to submit to another society that has another rule,” Sandra Guarani Nhandeva says.

The Indigenous residents often face prejudice from their neighbors, she adds. “All the time we feel an embarrassment, because the people who live in the surroundings are making fun of us, mocking us,” she says. “[They] often yell ‘uh-uh-uh’ to us and then start to imitate us, mock us … It’s a daily embarrassment.”

She recalls a case of an Indigenous resident who ordered a car through a ride-hailing app but was rejected by the driver after he saw that she had painted her body all over for a presentation. “So we go through all this. We Indigenous people are very discriminated against in Brazil as if we were strange, as if we were bothering the Brazilians. The Indigenous people who live in the city are completely invisible,” Sandra Guarani Nhandeva says.

Arrested for ‘thinking of robbing’

Rio de Janeiro has always occupied a special place in Brazilian history. It was the capital during different periods: of the Portuguese colony of the State of Brazil (1763-1815), then of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves (1815-1822), of the Empire of Brazil (1822-1889), and of the Republic of the United States of Brazil (1889-1968) until 1960, when the country’s political power base shifted to the newly built Brasília. That year, Rio de Janeiro was transformed into a city state with the name of Guanabara; in 1975 it became the capital of the state of Rio de Janeiro after its merger with Guanabara. Its royal heritage is reflected in the imposing Portuguese-style buildings in the city center and other neighborhoods, built for the Portuguese royal family, who moved their seat of empire here from Lisbon in the early 1800s.

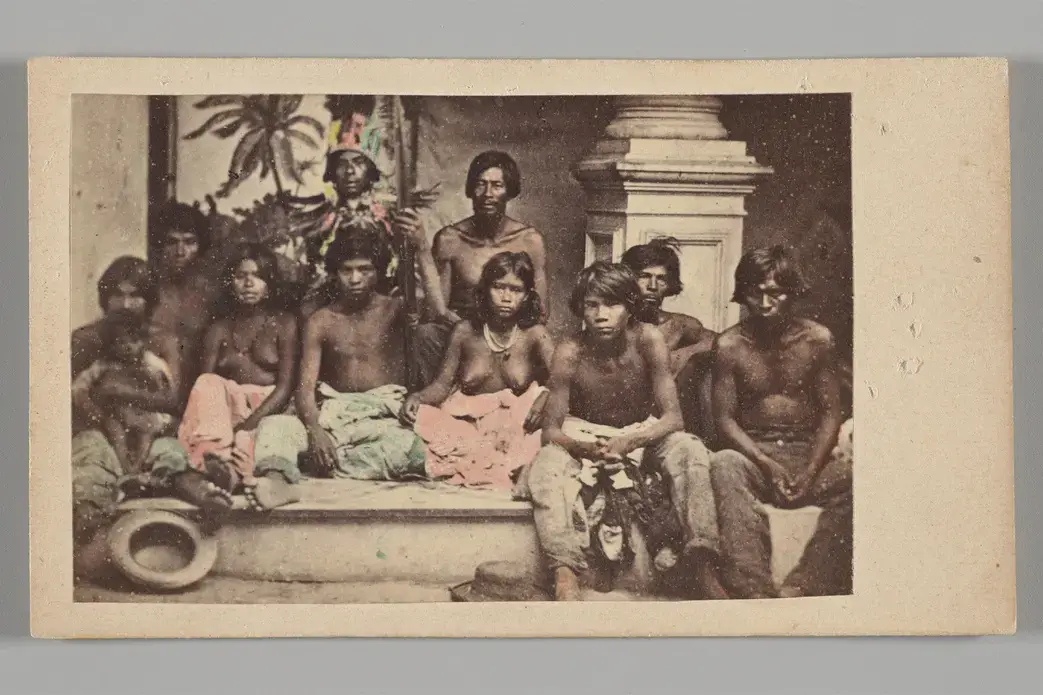

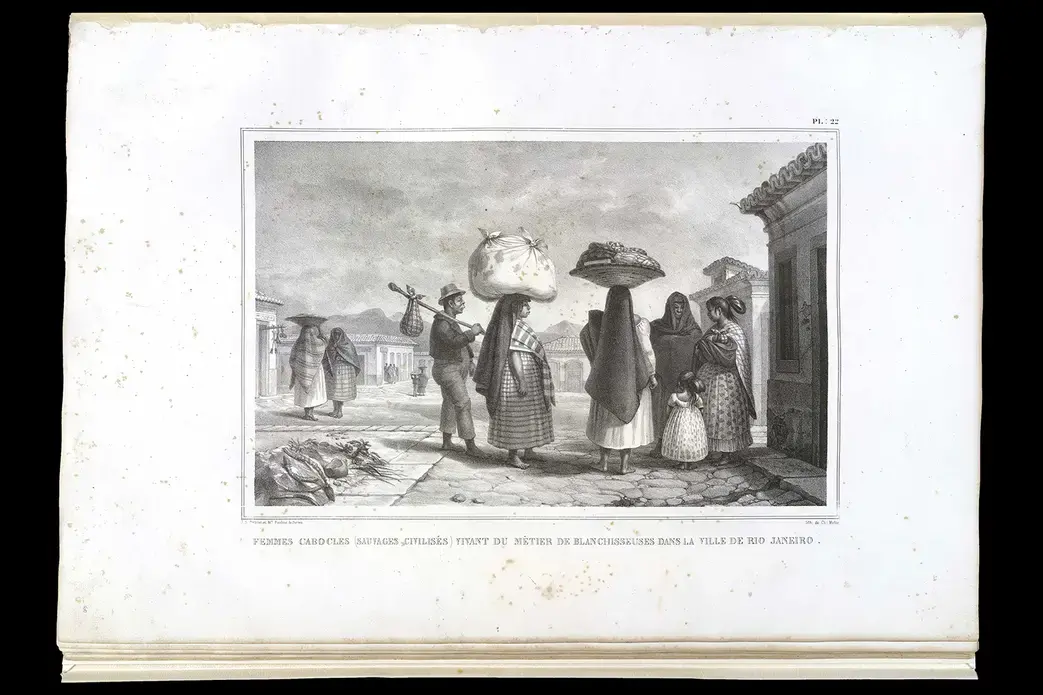

Indigenous people from all over Brazil came to Rio over the centuries. The National Library’s archives document the Indigenous presence in Rio from neighboring cities like Niterói, who crossed the bridge over Guanabara Bay to sell their art downtown, says Ana Paula da Silva, the historian. There was also a large contingent of Indigenous people from other states, called provinces at the time, who worked in private homes, as rowers, and as “forced recruits” for the army and the navy, da Silva says.

“What we can map through this documentation is that their reality was very difficult. They lived in the barracks in conditions that were … very unhealthy, earning low wages, and with that they deserted,” she says. “It is common for us to find in the navy documentation many Indigenous people who deserted due to these working and living conditions and forcible recruitment."

“They imagined a reality and [when they] arrived here they had another reality,” she adds. “So many deserted, went whale fishing … many Indigenous children [worked] in private homes taking care of other children … So the relationship between the Indigenous people and the city of Rio de Janeiro was a very close relationship, not only culturally, not only linguistically, but also building these heritages.”

But all this is buried in the city’s archives, leading to the “erasure” of Indigenous people from Brazil’s history, says José Ribamar Bessa Freire, a professor coordinating a program of study of Indigenous peoples at UERJ. He led a group of 12 researchers who searched 25 large archives in the city of Rio de Janeiro over the course of three years.

The initiative is part of a major project, led by anthropologist Manuela Carneiro da Cunha and historian João Monteiro, focused on unearthing documentation about Indigenous people in the archives of all Brazilian capitals to answer the question: “Why do Indigenous people not appear in the history of Brazil?” For Bessa, the answer is, “Because there is no documentation about it.” So the task force was formed to find these records, he says.

“All documentation about Indigenous people throughout Brazil is here [in Rio],” Bessa says, noting that as Rio was Brazil’s capital, it’s archives are national in scope, including the National Archive itself, which wasn’t moved to Brasília.

It wasn’t an easy task, Bessa says, as some archives even denied the existence of any Indigenous-related documents, which called for manual searches among piles and piles of documents.

That was the case with the Public Archive of the State of Rio de Janeiro, he says. “I said, ‘It’s not possible. We’re coming from the National Archive, [where] there are a lot of letters from the Ministry of Agriculture to the president of the province asking for demographic data of more than 16 indigenous villages in the 19th century.’

“Then [the archive manager] said, ‘There isn’t anything, professor, look at the catalog.’ Then I looked at the catalog and there was absolutely nothing about Indigenous people. The students almost killed me together because I said, ‘Let’s search pack by pack, document by document,’” Bessa recalls.

As they were about to give up, he says, “we found in the bundle a correspondence of the baron de Araruama, who was a general director of Indigenous [affairs] in 1945.” Through this correspondence, the researchers gleaned demographic data on the Indigenous presence in Rio de Janeiro, both the city and the state, Bessa says.

Bessa is also a professor in the postgraduate program in social memory at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Unirio) and co-author of the book Os aldeamentos Indígenas no Rio de Janeiro (Indigenous Villages in Rio de Janeiro), which documents the presence of Indigenous people in the whole Rio de Janeiro state. “For you to see the concealment process, it starts in the files themselves,” he says.

The researchers’ thorough search of all archives in Rio de Janeiro state highlighted the “terrible” conservation of records related to Indigenous affairs, Bessa says. In some cases, he says, documents were in basements with “rats and cockroaches,” ready to be burned; in one archive, the records were in a parking lot with “bicycles on top of the packs.” “That’s to answer your question about the historical erasure,” Bessa tells Mongabay.

In some situations, he says, researchers also had to cross-check information from notary, parish and municipal archives to resolve inconsistencies in the Indigenous records. Parish archives are “relatively well organized,” Bessa says, and yielded many records of Indigenous people being baptized, with their Indigenous names listed alongside their Christian names. Those same individuals never turned up in death certificates held in notary archives between 1889 until the end of the dictatorship in the 1980s, Bessa says. After going back to the parish files, he found that the notaries had “killed them civilly” by listing them under their baptismal names on their death certificates, and omitting any mention that they were Indigenous.

Bessa also highlights findings from the records of the Rio de Janeiro Police Court in the National Archive, with almost 400 handwritten books of arrests made in the city. He says the researchers were “scared” by the sheer number of Indigenous people arrested during the urbanization of the city. The court police, he explains, was created in 1808 by John VI, king of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves from 1816 to 1825.

One case in particular caught Bessa’s attention: that of an Indigenous man ordered to work in construction after being arrested for “thinking of robbing,” as reported by the police chief at the time. Intrigued, Bessa reached out to an associate judge who explained that the penal code at the time prescribed community work as a penalty. That led Bessa to the conclusion that the city of Rio needed ways to find free or cheap labor, as the African slaves were all at the coffee plantations in the Paraíba Valley, outside the city.

“And then the Indigenous [people] were arrested as a form of recruitment. It didn’t matter if they committed a crime or not. [The method was] to arrest [an Indigenous individual] and invent a crime like he was thinking of robbing, and setting [a penalty] of eight months of [compulsory] work to renovate the Passeio Público, for example,” Bessa says.

An irrecoverable part of the Indigenous history in Brazil was destroyed by a fire in September 2018 that destroyed unique archives and objects from the National Museum, which experts say told the “other history of Brazil.”

“If you think of the National Museum as being the construction of a generation of researchers, apart from many governments, you’ll see that what was built [in research] took decades and decades and decades to be built,” says José Carlos Matos Pereira, the sociologist. “And that by losing this material, there is no way to recompose it because they were unique materials, donations, collections. And materials collected over a lifetime. People will not have access [to it anymore]. Some of the memory and history was lost. And in relation to the Indigenous people, we can think of them as the silenced in writing and in history. Because the Brazilian state does not recognize the conflict, the extermination, the murder [of Indigenous people].”

Matos was pursuing his postdoctorate at the National Museum shortly before the disaster, and recalls being extremely worried about the prospect of a fire when he saw all the exposed electrical wiring. “It wasn’t for lack of warning. It wasn’t for lack of requests for repair, money, financing. Now there’s no way to rebuild what was lost. The museum that becomes the museum of today will never be the same as the museum of the past.”

José Guajajara, who studied linguistics at the National Museum, agrees. “There was an entire collection, a large collection of national Indianism, which concerns ethnographic and mainly languages, matrices of Indigenous languages and Indigenous land as well. That’s why it was criminally burned on September 2, 2018.”

Reviving history: ‘We exist’

Rio de Janeiro, a metropolis blessed with beaches, waterfalls, forests and mountains, among other natural resources, and gilded by a legendary party life, attracts people from other parts of Brazil and abroad, including Indigenous people.

Among them is Tereza Correa da Silva Arapium, 56, who was born in the village of Andirá, in the Lower Tapajós River region in the Amazonian state of Pará. She left her village at the age of 12, moving to the city of Santarém to study because there was no school in her village. She later moved to Rio to pursue her dream of working in tourism, and has now lived here for half her life.

Tereza Arapium says she initially shed her Indigenous culture and started living a “non-Indigenous life,” going to bars, parties, carnivals, samba, and more. This lasted until 2013, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer and returned to her village for traditional treatment. She says she stayed there for two years, completely disconnected from the non-Indigenous life and totally immersed in her culture and ancestral roots. She says the shaman told her she would be healed, and she was, she says.

“From that moment I made a decision that I was going to leave ‘city life’ [and] defend nature, because it cured me. I would defend nature and my people, I would defend [the Indigenous and] would dedicate myself to this mission. And from that moment I became an activist,” she tells Mongabay from her hammock in her apartment in Catete, a neighborhood that in 2010 was home to 90 Indigenous people, according to the census. She deliberately chose not to have a bed. “I don’t give up sleeping in the hammock,” she says.

Like many other places in Rio, Catete comes from the Tupi language. It means “immense forest” or “closed forest”; it also refers to a branch of Carioca River that skirted the Glória hill and flowed into the sea. The neighborhood sits on land that was once the Indigenous village of Uruçumirim. From 1840 onward, the area was a favorite for the colonial nobles to build their mansions and settle down. Among the most prominent was the baron of Nova Friburgo, who commissioned the construction of the Palácio do Catete (Catete Palace), which later served as Brazil’s presidential residence for more than 60 years. Eighteen presidents took up residence here, the most famous of them Getúlio Vargas, who committed suicide in the palace in 1954.

Tereza Arapium says she came back to Rio to “have a voice, bringing the forest voice.” She started participating in local social movements and ran as a city councillor in the 2020 election — the only Indigenous woman candidate in Rio’s election — to fight for Indigenous rights. Though she didn’t win, she wanted the issue on the agenda in Rio, to press the urgency of declaring that “we exist.”

“In Rio de Janeiro, native peoples have no visibility, their rights are totally denied because they are not recognized in Rio de Janeiro as Indigenous,” she says. “That’s the greatest invisibility of native people in [the whole of] Brazil. There will only be a solution to the Indigenous peoples’ issues when we get there — when we get to the legislative and executive powers, when we sign projects and public policies.”

Despite her loss in the election, Tereza Arapium says she felt victorious because she gained many supporters and shed light on Rio’s Indigenous population. She says her campaign was “revolutionary” as it used tree leaves instead of paper pamphlets and stickers, as an example that it was possible to do a sustainable campaign.

However, she describes many examples of prejudice she faced in Rio, especially when she used traditional Indigenous clothing and body paint during her campaign, and for being both a woman and Indigenous.

“Being Indigenous in Rio de Janeiro is like being a strong fighter to fight against prejudice and racism, which affected us a lot, and invisibility. As if the Indigenous were not part of this city … As if we were not part of the people of Rio de Janeiro. When we put our paintings, our graphics, people look at it in such a way, admired, as if that was something they’ve never seen in their lives. It was like you became an attraction,” Tereza Arapium says, noting that when she goes unadorned with body paint, she is “not so discriminated against.”

She also complains about the lack of specific health and education services for Indigenous people in Rio, but which exist in Indigenous reserves; and about the lack of a cultural space in the city where Indigenous people can exhibit their arts and craftsmanship, sing and practice their traditional rituals.

“I only know that I have a mission in Rio de Janeiro and I have a mission in my village. I’m the chief of my village so being the chief is a mission, right, it’s not a position,” Tereza Arapium says.

“My dream? It is to see the environment preserved, without such great destruction, and my dream is that one day we can see nature in peace.”

Despite being from the village, Tereza Arapium has only recently started learning Nheengatu Tapajoara, the ancestral language of her people. “My people were totally catechized, whitened by the Portuguese [colonizers],” she says. “Our language was practically extinct because of the ban. When they arrived they banned our language and imposed Portuguese, so our ancestors were threatened, just like us, our culture was totally banned.”

She says she also saw the culture of her people being attacked with the arrival of Christian missionaries in her village, preaching Catholicism and labeling the shamans “evil.” Another example of the “whitening” of her people, she says, is being registered in official records as having been born in the city of Santarém instead of in the village. This happened to her and all the members of her family, she says.

The online Nheengatu Tapajoara course, Tereza Arapium says, is a “great discovery.” She found she already speaks Nheengatu without being aware of it, because most of the names of fruits and fish come from the Tupi language.

Now, she says she’s fighting for the “revival” of Indigenous history in Rio, which is progressing slowly through academic works.

“One of our [campaign] proposals was to do tourism based on the history of the native peoples who lived in Rio de Janeiro before the arrival of the invader,” she says, noting that this is still one of her goals.

“There’s an arduous mission in Rio de Janeiro, it’s not easy, which is this revival of [the real] history because of the invisibility of our people in Rio de Janeiro,” Tereza Arapium says, highlighting the Indigenous people’s fight to tell their own history. “The history that is told in schools, in books, is the history of the colonizer. It’s the story that is interesting for the colonizer, not for the Indigenous … It’s unfair that the history of native peoples in Rio de Janeiro is totally erased.”

Sandra Guarani Nhandeva, the schoolteacher, echoes Tereza Arapium, urging Indigenous people to get organized and united in the city to fight for their rights and overcome all the challenges. “Otherwise,” she says, “we will continue to be invisible.”

To see interactive maps, visit Mongbay.

To read this story in Portuguese, click here.

This story is part of the series Indigenous people in Brazilian cities, which received funding support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting’s data journalism and property rights grant.

Maps: Ambiental Media / Juliana Mori.

Infographics: Ambiental Media/Laura Kurtzberg

Data research and analysis: Yuli Santana, Rafael Dupim and Ambiental Media

Banner image: “Civilized Gouaranis employed in Rio Janeiro as artillerymen,” by Charles Étienne Pierre Motte. Image courtesy of Fundação Biblioteca Nacional.