Emma Chen loves visiting Macau. As a student of Portuguese at Guangzhou University in China, traveling to the region is the only way she can get real-life experience speaking the language, since flying to other Portuguese-speaking countries is out of her budget. It wouldn’t be surprising, however, if Chen went back to Macau in 10 years only to discover she can no longer find conversation partners there.

The numbers of Portuguese-speaking residents of Macau are decreasing, and so is the influence of the European country in the region’s culture, traditions and cuisine. For a place that was once colonized by Portugal, the data is alarming.

The consul general of Portugal in Macau and Hong Kong, Vitor Sereno, said the Macanese and Portuguese communities combined add to around 15,000 residents in the region. These two ethnic groups represented 2.5 percent of the total population of Macau in 1991, compared to 1.6 percent in 2001 and 1.3 percent in 2011.

“Since I picked up Portuguese, I’ve been to Macau seven times in two years,” Chen said. “Each time I come it’s harder to find people to speak the language to.”

Sereno is concerned with the numbers as well. The consul general has seen a lack of Portuguese-speaking residents when hiring for his own office.

“At the consulate here in Macau we have around 160,000 Portuguese passports registered, but only 10 to 15 percent of those people can actually speak the language,” he said. “It’s clearly a problem when the consulate itself cannot find bilingual people to hire."

In order to incentivize the learning of Portuguese, the consulate has been working with Instituto Portugues do Oriente (IPOR). Its director, Joao Neves, said the institute is willing to “offer any resources necessary to make sure there is a growth in interest.” Currently, more than 2,000 students are enrolled in weekly Portuguese classes, but the number is still too small in Sereno’s and Neves’ eyes.

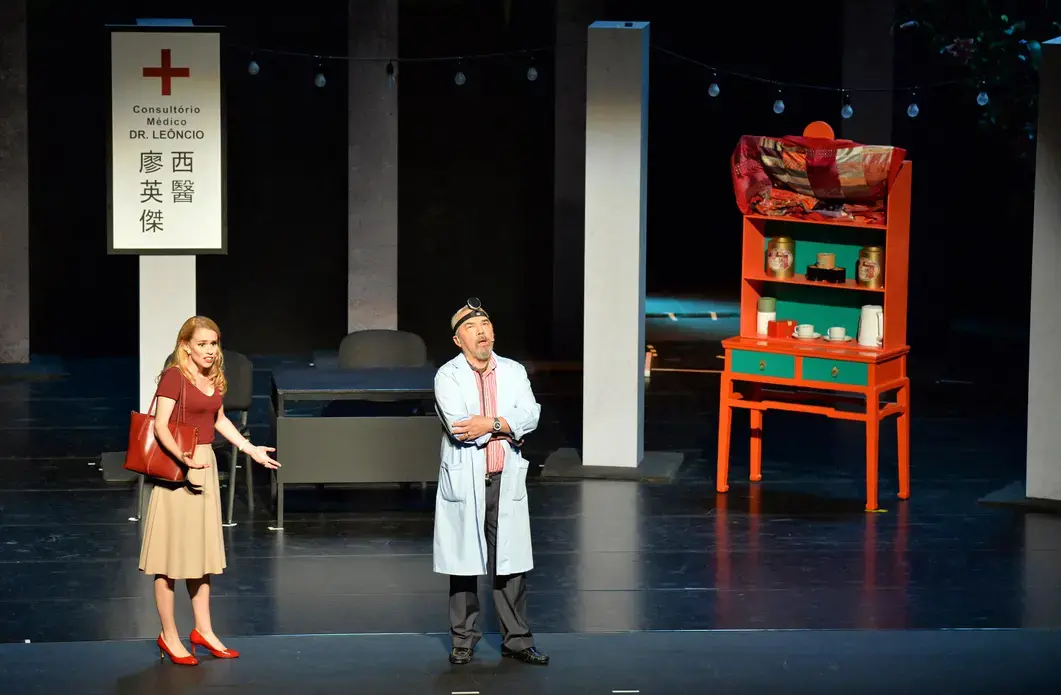

The key is that knowing a language is the first step in embracing its culture. When residents of Macau speak Portuguese, they can understand the music, theater and film and TV content produced in Portugal. Chen, who calls herself a “Portuguese-fanatic,” said that was one of the main reasons that she picked up the language at first.

“When I was in high school, I listened to a catchy Brazilian song and then became fascinated by Portuguese music,” she said. “The problem was not being able to understand anything they were saying.”

Chen said that, at first, she didn’t feel as inclined to expand her consumption of Portuguese culture to movies and literature because, unlike music, it was hard to enjoy it without speaking the language. It was then that she enrolled in a Portuguese class at her university.

The efforts to help the region maintain its roots and cultural origins extend to more than just the language, of course. Now known for its massive casinos and tall skyscrapers, Macau has another distinguishing characteristic: Its historic center is considered, since 2005, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, due to the well-preserved, Portuguese-influenced buildings.

For 450 years, Macau was a colony of Portugal. By the 1800s, pasteis de nata and bolinhos de bacalhau were already the go-to foods in Macanese establishments. In 1976, however, things began to change. The Portuguese government decided to relinquish all of Portugal’s overseas territories. By 1999, Macau had been handed over to China and became one of the country’s special administrative regions (SAR).

The handover marked the end of European colonialism in Asia. Portuguese remained an official language of the region, but today only 0.6 percent of households have Portuguese as their mainly-spoken language.

“The switch in power clearly affected the community, making it harder for Portuguese traditions to be spread,” Rosina Choi, from the communications department of Cultural Affairs Bureau of Macau, said.

Choi works at the Instituto Cultural de Macau, a cultural institute run by the Macau government that plans, organizes, and runs events designed to celebrate and promote local and international culture in the region. One of the main goals of the institute, in recent years, she said, is to promote Portuguese traditions.

“We have noticed that even though there is a reduction in the presence of Portuguese content in the media and popular culture, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the locals are not interested in it,” she said.

Take the Lusofonia Festival as an example. The event, which celebrates Portugal and its former colonies, has been held for 19 years and the number of participants has consistently increased. The 3-day carnival attracts an average of 20,000 visitors, and is a favorite between residents and tourists.

“I come to Macau every year for the Lusofonia Festival,” Chen said. “This is a unique opportunity for me to learn more about their culture; it’s a lot cheaper than going to Portugal.”

And that is exactly what the Instituto Cultural de Macau is trying to capitalize on. Being one of the few places in Asia, and the most recent, to have been colonized by Portugal, Macau is in a privileged situation to position itself as the center of Portuguese culture in the continent. The problem is that, although the local community might enjoy the Lusofonia Festival, this does not translate into an interest in other aspects of the country’s traditions.

“I talk to people who attend the festival with hopes of finding someone as enthusiastic as me, but it rarely ever happens,” Chen said. “What I can do is go back to Guangzhou and tell my friends about what I learned. Then maybe they will become into it as well.”

It’s because of people like Chen that IPOR, the Portuguese consulate and the Instituto Cultural, are all investing in events, classes, and programs that give the local community exposure to the European country’s traditions. As Choi said, it’s not that the people are not interested, but that they might not even know that they enjoy listening to fado or reading Luis de Camoes.

Macau is one of the last remainders in Asia of hundreds of years of a strong, rich, dominant Portugal. It’s the reason UNESCO made the historic center of the city a World Heritage Site—and why Portuguese is still an official language of Macau even though Portugal no longer controls the region.

If the numbers continue to decrease, this might not only represent the definitive end of Portugal as a world power, but also the start of the disappearance of its culture around the globe. And for that reason, Emma Chen and the world better hope people like Choi, Neves and Sereno succeed in their missions.