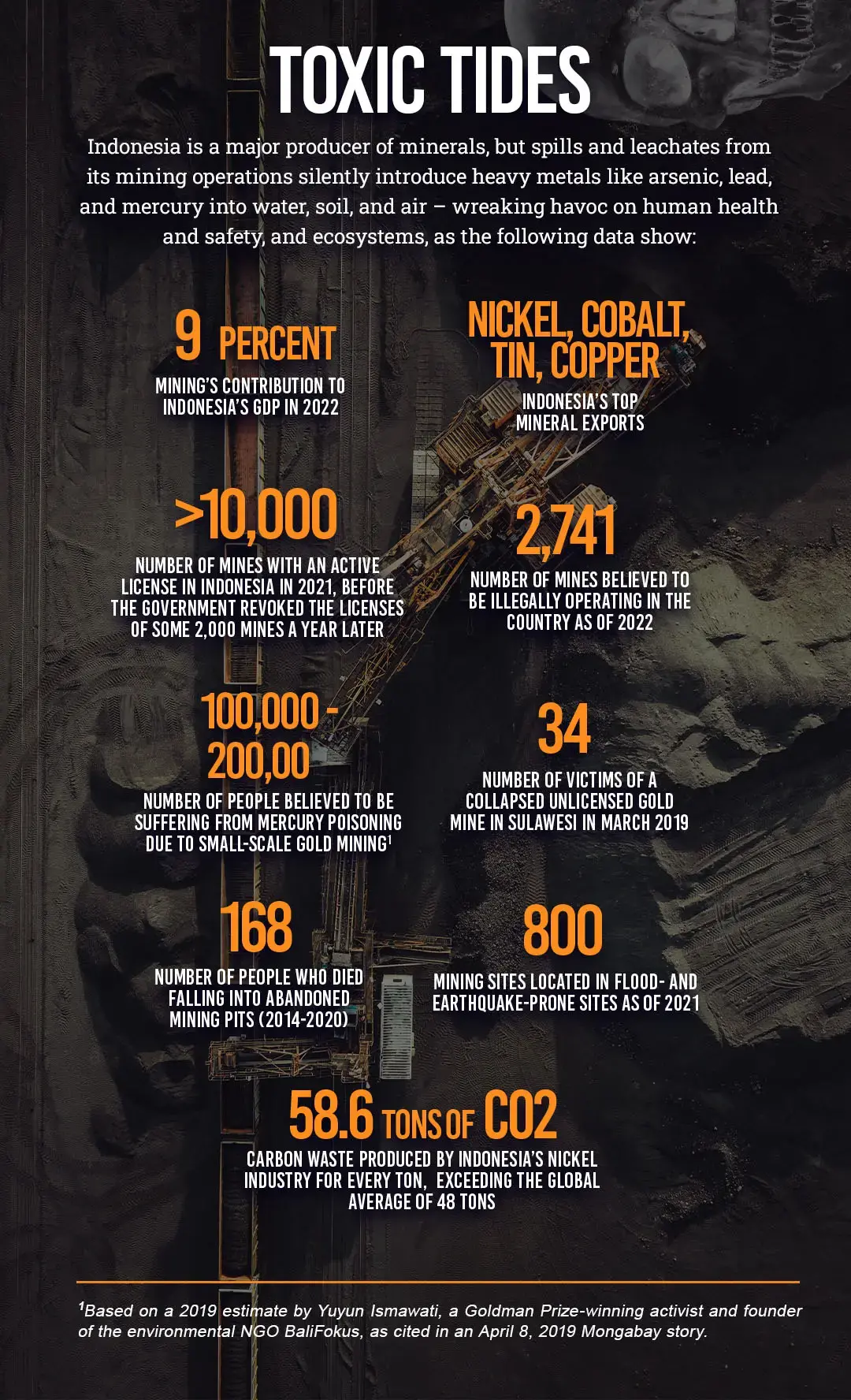

Land grabbing, loss of traditional livelihoods, as well as rising health and environmental concerns are controversies hounding Indonesia’s grand global ambitions for its nickel industry.

Indonesia’s Central Statistics Agency (BPS) is set to do another of its Happiness Level Measurement Survey this year, and chances are North Maluku will again top the Happiness Index among the country’s 38 provinces. After all, with its breathtaking scenery and an annual economic growth that has been consistently in the double digits, it may be hard to find anyone with a litany of complaints in the remote province of some 350 islands.

Or wouldn’t it?

Indonesia supplies nearly half of the world’s nickel needs but it wants to grow that some more. North Maluku is among the country’s four main sites for nickel mining and downstreaming. As of 2022, North Maluku has already attracted more than US$9.8 billion (IDR150 trillion) of investment, according to the Investment Board Agency.

Thanks to its flourishing nickel smelting and downstreaming activities, the northeastern province recorded a whopping increase in regional gross domestic product in 2022, posting a total of more than IDR21 trillion ($1.3 billion) from 2020’s IDR3 trillion ($192 million). BPS also reported that North Maluku experienced 23.89-percent economic growth in the second quarter of 2023 alone, or five times the average national economic growth.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Yet, poverty remains a problem in North Maluku. In the first quarter of 2023, poverty reached 6.46 percent or more than 83,000 people, according to BPS. Interestingly, Central Halmahera — home to the sprawling Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) that includes Weda Bay Nickel (WBN) — has one of the highest poverty rates among the province’s regencies: 12 percent, far above that of the province.

Bhima Yudhistira, researcher at the Center of Economic and Law Studies in Jakarta, is not surprised. He says that investment in the mining sector is not inclusive, meaning only a group of people with certain qualifications may benefit from the booming nickel industry. “This is one of the aspects as to why there is an income gap and inequality,” says Yudhistira. “The local communities may not benefit from the nickel industry because of a lack of skills.”

Yudhistira says that the nickel downstreaming in Indonesia has even disrupted local economies that once relied on farming and fishing. As more farms and forests are cleared and the sea is polluted, local communities may lose their source of income and be trapped in poverty, he says. “This is what it means that the nickel industry is threatening the living space of local communities,” he adds. “Fisherfolk have to fish further, for example.”

Abdullah Ambar, a 63-year-old fisher, is a frontline witness to this. A resident of Lelilef Waibulan, a small coastal village off the Weda Bay in Central Halmahera Regency, he recalls. “Back in the day we used to fish close to Lelilef around Weda Bay and Tanjung Ulie, and the catch was very good and enough to support the families. But now it’s impossible…. I have to go further if I want to get a good catch, but the operational cost, of course, keeps increasing.”

“It all started when the company [WBN] came,” says Ambar. “(Since then) our lives have not been the same.”

The father of seven says that the dense mangrove formations around Weda Bay used to be the perfect fishing and breeding ground for marine life. But after nickel deposits were discovered in the area in the 1990s, forests and farms gradually turned into mining concessions, mangroves were destroyed to make way for an industrial complex, and the fish population in the coastal waters began to decrease.

Big players in a small village

Since becoming fully operational in Central Helmahera in 2005, WBN has acquired more than 76,200 hectares of land. More than 35,000 hectares of these are inside forest areas while thousands more tracts were once owned by locals such as Ambar.

“I sold my land to WBN long ago because I had no choice,” says Ambar. “My farm was surrounded by mining concessions so it’s difficult to access the land. Then I bought a few hectares of land outside of the village that are now farmed by my kids.”

A multinational company with the French mining firm Eramet as the largest shareholder, WBN has been accused of land grabbing and deforestation of protected forest areas in Central Helmahera due to overlapping permits and regulations. It is also said to have acquired land without proper compensation of at least 154 families of ethnic Sawai who live around the concessions, according to the National Indigenous Community Alliance (AMAN).

But the company has managed to weather such allegations. In 2018, as part of a national strategic project to boost domestic nickel ore processing, the central government established the IWIP, a multi-billion-dollar nickel-processing industrial complex led by Chinese companies — Tsingshan Holding Group, Huayou Cobalt Group, and Zhenshi Holding Group, in Lelilef, along with WBN and other international companies.

Built on 5,000 hectares of land, IWIP has smelting and battery production facilities, as well as captive coal power plants to power the whole complex.

Lelilef is now an economic hub, attracting newcomers from across the country to work on the mining concessions or to open up businesses. Once a secluded coastal village surrounded by mangroves and dense forest with just a few hundreds of residents, Lelilef has become one of North Maluku’s most populous villages, with more than 5,000 inhabitants.

Polluted waters, unhealthy fish

One wonders, though, how many of the original locals took part in the BPS’s happiness survey, which was based on three factors: satisfaction on life, feelings, and meaning of life.

Ambar, for one, doesn’t sound too happy. He says that as the fish population keeps decreasing around Weda Bay, many fishers have given up and looked for other means of livelihood. The few who still fish do so mainly for their own family’s consumption since they usually catch too little to sell.

Ambar himself realized a few years ago that he would have to have bigger boats that would be able to travel longer distances if he wanted to make a decent living. He is now Lelilef’s only fisher who can go much farther from the coast. He sails as far as Raja Ampat in Papua, catching tunas, halfbeaks, and giant trevallies.

Ambar says he can catch 10 tons of fish in a good month, or what he used to get just by staying close to shore. But operating big fishing boats is costly, he says; some 40 percent of his gross earnings now go to operating expenses.

Yet fishing closer to home is no longer a viable option — and that’s not only because of the dwindling fish numbers. Research conducted by the media outlet Kompas and Khairun University, Ternate in September 2023 showed that waters off Lelilef in Weda Bay are heavily polluted with heavy metals. The research team took water samples from a depth of 15 meters and found that chrome hexavalent, nickel, and copper were above or just below the quality threshold stipulated by government regulations. Nickel in particular was found to be 0.09 mg/liter, above the quality threshold of 0.05mg/liter as regulated by the government.

Fish taken as samples and then sent to the Marine Health Laboratory at the Bogor Agriculture Institute also showed damages to liver, kidneys, and flesh allegedly due to heavy metal pollution.

“We found the fish to be unhealthy,” researcher Muhammad Aris was quoted by Kompas as saying. “Cells and tissues show damages, which make them unable to reproduce normally, which means the fish population in the waters are decreasing and endangered.”

For residents of Lelilef, rivers used to be their source of livelihood. But as nickel-related activities intensified in their village, they say the rivers began turning dark brown, allegedly due to heavy sedimentation from the deforestation at the upstream area.

A main Lelilef water tributary, the Sake River, has also been rerouted to serve as IWIP’s water source. The river’s rerouting has brought considerable impacts on the local environment, such as erosion, frequent flooding, decreased water quality, and changes to river morphology, according to IWIP’s own environmental impact analysis.

“We used to rely on rivers and creeks for our daily needs,” says Ambar. “We can’t do that anymore. We have to drill deep wells and buy drinking water by the gallon.”

More muddy waters

In Sagea, a village about 28 km east of Lelilef, residents have also reported an increase in the pollution of their main river since April 2023.

Sagea River is part of an intricate underground rivers and karst cave system in Central Halmahera. The upstream area flows through Bokimaruru Cave, a popular tourist destination. For generations the Sagea River has played a vital role in the livelihoods of the Sagea people.

But during the dry season last year, Sagea resident and youth activist Adlun Fikri says that the river turned dark brown, which was unusual as it usually only turned light brown during the wet season.

“We noticed these changes in April, but it was not until July (2023) that we finally documented them,” says Fikri. “The Sagea River was very muddy throughout August (2023).”

Residents also analyzed satellite imagery between March and July last year, and found deforested areas as a result of mining-road construction within WBN’s concession site.

In August, residents filed a complaint with the environmental agency, demanding that WBN and other companies operating in the upstream area halt mining activities until further investigation. The residents presented photos and videos as evidence of the damage allegedly wrought by WBN. But an investigation conducted by the environmental agency concluded that the mining activities were not the cause of the pollution.

In a November 2023 Kompas article, PT IWIP was quoted as saying that it had installed a water quality monitoring system. It claimed to “have protected the area” for the benefit of fisherfolk and to ensure that its operations such as “building sedimentation pond and silt curtain on the tributaries within IWIP” would not have significant impact on the sea.

The Ministry of Environment for its part stated that together with the regional government, it has implemented regulations to prevent companies from polluting the environment. Still, the same article had Sigit Reliantoro, an official with the ministry, remarking that some companies were still violating the regulations, including IWIP.

In the meantime, the central government is confident that Indonesia is on track to dominate the global nickel market even more. Maritime and Investment Coordinating Minister Luhut Pandjaitan has even reported that the country’s nickel exports increased 745 percent from 2017 to 2022, with the production amounting to three million metric tons and valued at IDR 504 trillion (US$36 million) .

“People talk about economic benefits,” says Ambar. “But what’s the benefit when we talk about social and cultural aspects? There’s no guarantee by the company that our children’s life would be better. I wonder about their future.”