The press’ rough draft of the history of race in St. Louis, Missouri and Illinois got most things wrong.

In the early 1950s, a group of young civil rights activists – Irv and Maggie Dagen, Charles and Marion Oldham and Norman Seay – led a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) sponsored sit-in of lunch counters in segregated downtown St. Louis.

Richard Dudman, a young reporter for the Post-Dispatch, ran across the protest and hurried back to the office with the big story.

The editors told the future Washington Bureau chief to forget it. They knew about the protests but weren’t writing about them because it might trigger violence. Avoiding a riot was a preoccupation at the paper where big glass windows near the presses were bricked over just in case. There never was a riot, a fact often cited as a reason St. Louis never seriously grappled with race before Ferguson.

Joseph Pulitzer II was the publisher who built the Post-Dispatch into a great American newspaper and a leading progressive voice for change. He and the paper generally supported civil rights, as opposed to its competitor the Globe-Democrat that consorted with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s dirty tricks against the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Pulitzer urged reluctant editors to consider hiring blacks in the 1950s. But Pulitzer didn’t want to go too far.

In 1950 Pulitzer thought a letter to the editor from black postal clerk Henry Winfield Wheeler was “an almost perfect statement of the Negro cause.” At Pulitzer’s suggestion, reporter Donald Grant was assigned to write a story about Wheeler. Wheeler wrote a letter to Grant saying blacks want “the same treatment under our Constitution as every other American citizen” including the right to marry anyone of their choosing.

“The persons, be they Black or White, who object to this right are Fascist in their thinking. I want my daughter to have a right to go to a Public School, not as a Colored girl, but as an American girl enjoying the same opportunity as her White playmate. I want my boy and my girl to be given the same opportunity according to their ability and efficiency as any other individual. I want the right to eat and sleep in any hotel that I can pay the price. I want the right to live anywhere that I choose in any neighborhood so long as I am a law-abiding citizen. I want the right to go into any Theater or Public Place just like all other Folks. I want the right to enjoy peace and prosperity under the stars and stripes, which rights have been bought by all of us by blood and tears and toil. I want Human Dignity.”

This basic statement of human rights was too much. Grant wrote to Pulitzer “that in my opinion an interview with Mr. Wheeler would not be suitable for publication.” Pulitzer agreed, adding, “I fear I made a mistake” suggesting the interview. “I agree the publication of his views would do the Negro cause more harm than good.”

In 1954 the Post-Dispatch supported the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board decision desegregating public schools. Again Pulitzer was cautious.

“I advise going slow in pressing the subject of non-integration in hotels and restaurants, lest we do the cause of non-integration more harm than good.”

Irving Dilliard, the editorial editor, didn’t follow the advice in his editorial the next day: “More Powerful than All the Bombs.” It said the justices of the Supreme Court “will be associated as long as this Republic stands with a great and just act of judicial statesmanship” that affirmed “the pledge in the United States of the worth and dignity of the humblest individual means what it says….Nine men in Washington have given us a victory that no number of divisions, arms or bombs could ever have won.”

One of the big Post-Dispatch projects of the 1950s was “Progress or Decay,” a multi-part series advocating the clearance of slums to be replaced by public housing. The slums, such as the Mill Creek area around the railroad tracks east of Grand Blvd., were cleared, but residents were scattered to the winds and public housing projects soon were their own slums. Laclede Town, which replaced the Mill Creek slum, had to be torn down and Pruitt Igoe was dynamited.

Jefferson Bank

St. Louis never had the riot that Post-Dispatch editors feared. The closest thing was the 1963 Jefferson Bank protest, which began two days after Martin Luther King’s March on Washington.

President John F. Kennedy, who had just introduced the Civil Rights Act that year cautioned civil rights leaders two months before the Washington march that it was “ill-timed.” He added, “We want success in Congress, not just a big show at the Capitol.” King responded to Kennedy, “Frankly, I have never engaged in any direct-action movement which did not seem ill-timed.”

Demonstrators at the Jefferson Bank were told the same thing – that they were setting back their cause.

The pro-civil rights Post-Dispatch editorial page wrote, “The impatience of the civil rights movement here is understandable and justifiable, but does it not now owe the business efforts to end discrimination a chance to prove successful? Demonstrations that stop business can be as self-defeating as they are unfair.”

William L. Clay, then an alderman, was sentenced to 270 days in jail for blocking the bank entrance. He went on to be elected to Congress where he served 32 years. He recalled : “The media was shameful in its biased coverage of the Jefferson Bank protests. The Post-Dispatch, Globe-Democrat, KMOX-TV, radio and the rest of the media became front organizations for the Establishment.”

They called demonstrators a “disruptive attempt by a small group of radicals seeking to harm the solid advancement in the city’s race relations.”

He pointed out the newspapers had no black reporters, ad reps or pressmen.

“The most the Post could point to was a black receptionist,” he said. “There were no blacks as newsmen or women in radio or television. … These facts that the media refused to publicize were as clear as a goat’s behind going uphill on a clear day.

“The Post, over and over, referred to the guilty and irresponsible (CORE) leadership and misguided defendants,” Clay added. And the Globe-Democrat tried to link CORE to communists. A Globe editorial called the protests “an extortion tactic in the guise of racial equality.”

Martin Duggan was a news editor at the Globe-Democrat at the time of the Jefferson Bank demonstrations. Recalled Duggan: “I considered Jefferson Bank not a villain. Why did they go after Jefferson Bank? It was never a big player. Maybe it was easier to intimidate. … The whole thing was unfortunate. It put an unfavorable light on the city and banks…Bill Clay was always antagonistic to the Globe. The Globe never approved of his tactics.”

Hoover and the Globe-Democrat

J. Edgar Hoover, the treacherous head of the FBI (amazingly the FBI headquarters still is named after him) orchestrated a campaign of dirty tricks against Rev. King to get him to kill himself. FBI Agent William Sullivan was placed in charge of the COINTELPRO – Counter Intelligence Program – targeting anti-war and civil rights leaders, including King.

Hoover and Sullivan had a different reaction than most Americans to the “I have a Dream Speech” during the 1963 March on Washington. Sullivan wrote: “In the light of King’s powerful demagogic speech. … We must mark him now if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security.”

One of Sullivan’s tactics was to send a hateful anonymous letter to King telling him to kill himself because of his “countless acts of adulterous and immoral conduct lower than that of a beast.”

The old St. Louis Globe-Democrat was an accomplice in the effort to discredit King, according to congressional reports. The Post-Dispatch used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain documents showing the Globe-Democrat’s complicity with the FBI’s COINTELPRO. The documents became part of the investigation of the House Assassinations Committee in 1980.

One 1968 FBI document read:

“The feeding of well chosen information to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a local newspaper, whose editor and associate editor are extremely friendly to the Bureau and the St. Louis Office, has also been utilized in the past and it is contemplated that this technique might be used to good advantage in connection with this program.”

And another:

“The St. Louis Globe-Democrat has been especially cooperative with the Bureau in the past. Its publisher [name deleted] is on the Special Correspondents List.”

On March 28, 1968, violence broke out at the Memphis sanitation march, the last protest Rev. King led. The FBI used it to send the message that King could not control a large march, such as the Poor People’s March planned for upcoming summer.

The FBI circulated a memo to “cooperative news media sources.” The House Assassinations Committee concluded the FBI ghost editorial resulted in a Globe-Democrat editorial two days later, right down to the misspelling of capital.

“Memphis may only be the prelude to civil strife in our Nation’s Capitol [sic].–FBI memorandum, March 28, 1968

Memphis could be only the prelude to a massive bloodbath in the Nation’s Capitol [sic] …–Globe-Democrat editorial, March 30, 1968

The House Assassinations Committee concluded that James Earl Ray didn’t read the editorial. He was in Birmingham that day buying the rifle he used to kill King.

The committee believed, however, that Ray’s brother, John, had read the editorial because he referred to it later after the assassination. On June 13, 1972, John Ray wrote to author George McMillan the following description of Dr. King:

“… A piece in the editorial sections of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat said that King led marches until he got, them stir [sic] up, then used a excuse to leave, while the dumb Blacks got their head beat in by police.”

The final conclusion of the House Assassinations Committee was that a St. Louis conspiracy most likely led to Ray’s assassination of King. It found evidence that a segregationist Monsanto patent lawyer, John H. Sutherland, and a former stock broker, John H. Kauffmann, had offered $50,000 to a career criminal to kill King. Sutherland, whose home office was decorated with Confederate memorabilia, was a John Birch Society member who founded the segregationist Citizens Council in Missouri and worked in the American Independent Party campaign for segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace. AIP leaders frequented John Ray’s Grapevine Tavern in South St. Louis. The committee could not close the link however and the Rays denied receiving any offer. Nor could the committee find evidence of a payment to Ray.

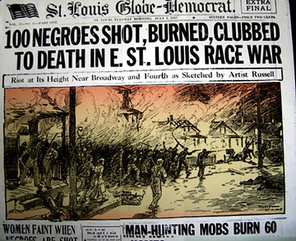

COINTELPRO in Cairo

Hoover and his COINTELPRO were active too in Cairo, Il. the sad town at the convergence of Ohio and Mississippi River with a history of lynching blacks in carnival atmospheres and printing postcards to commemorate the occasions. The lynching of Will James in 1909 was classic.

As the 1950s rolled around, Nathel Burtley and his friends wanted to swim in the Cairo pool. But a sign on it said, “Private: Whites only.” Burtley and his friends jumped in anyway and got arrested. The story featured prominently in an obituary last month when Burtley, who had gone on to be the first black superintendent in Flint, Mi., died of Covid-19.

By 1964 the white city government in Cairo was taking no chances. It closed the municipal swimming pool rather than open it to blacks.

Three years later, on July 16, 1967, Pfc. Robert L. Hunt Jr. was found hanged in the Cairo jail on July 16, 1967, setting off weeks of protests and violence.

Hunt was riding in an automobile with five others on the night of July 15 when Cairo police stopped the vehicle, allegedly for having a defective tail light. Hunt responded to the policeman’s verbal barrage with a barrage of his own, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found. He was charged with disorderly conduct and taken to jail. Police reported they locked Hunt into a cell at 12:30 a.m., and found him “approximately 30 to 40 minutes later…hanged by his t-shirt.”

The police story, based on a cellmate, was that Hunt was AWOL from the military and hung himself. The police report went missing and as did the cellmate and his name. Dr. Fred Crockett, physician and Illinois State President of the NAACP, contacted the FBI and called for an investigation. Among the suspicious elements of the death were:

Witnesses who viewed Hunt’s body saw bruises indicating he had been beaten; the police claim that Hunt was picked up because he was AWOL is contradicted by military documents praising his service; relatives say that Hunt was in good spirits and in no way suicidal before his visit to Cairo; the wire mesh at the top of his cell could not have supported Hunt’s weight.

But violence already had begun in Cairo in response to the hanging and top FBI officials decided not to investigate.

In an “urgent” July 19 memo to the Hoover, obtained by the SIU School of Journalism, the Springfield FBI wrote: “In view of the current turmoil where the National Guard, the state and local police are trying to contain a potentially violent situation, where vandalism and destruction of property have already occurred, it is recommended that no action be taken on Dr. Crockett’s complaint at this time.”

There was no action then nor in the 53 years since.

Washington was more interested in stemming the violence in Cairo and harrassing civil rights leaders. FBI documents show COINTELPRO sought to undermine the Rev. Charles Koen, who headed the Black Liberators, a Black Panther-style group in Cairo. FBI documents from 1969 show Hoover approved an operation proposed by the St. Louis office to send falsified “anonymous letters…(to) his wife regarding extramarital relations.” The hope was to “cause Koen to spend more of his time at home” in St. Louis. The letters were sent and the rumors also were printed in an “underground newspaper” called the Blackboard, which was printed in Springfield, Ill. and distributed in St. Louis.

The local paper, the Cairo Evening Citizen didn’t probe Hunt’s death. In a 1971 first-hand account from Cairo, J. Anthony Lukas of the New York Times described the paper’s bias against civil rights. Here’s a passage:

I’d agree to meet Leonard Boscarine, a young reporter for The Cairo Evening Citizen. I’d heard that the police had taken Boscarine’s camera away… and wanted to check that out.

“Yeah,” he told me. “…I started to take a picture and this cop shouted: ‘Hey, you can’t take our picture,’ shaking his club at me. Then Charlie Jestus, the assistant police chief, came over and said: ‘Give me that damn camera.’ Jestus knew me and I showed him my credentials just to make sure. But he took the camera and put it in his car. We got it back later, but the film had been ripped out.

“I was really mad, and I got even madder when I found out the paper wasn’t even going to report anything about it. The merchants told our advertising man we’d better be careful what we said about the Saturday events or they wouldn’t buy any more ads. …When I told Jim Flannery, the city editor [whose brother is a police sergeant] how disgusted that made me, he just looked up and said: ‘A man’s got to eat.’

“Hell, at journalism school (at SIU) they taught me a reporter ought to get both sides of a story. But down here people didn’t like that. In September, the Mayor and Police Commissioner came in and asked that I be fired….The next day, Boscarine was fired. So I went down to see David Cain, the young Texan who is editor publisher of The Citizen. Cain said he had fired Boscarine because he had become too “emotionally involved” in the racial story. “He was inclined to use his mouth too much and his ears too little,” he said. “Our readers just came to doubt the veracity of his reports.”

… Cain…conceded that The Citizen did not intend to publish anything about the camera incident. “In a big city you might feel you had to write about it because you couldn’t let the police get away with something like that,” he said, “but things are done differently in a small Illinois town.”

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found the events in Cairo so disturbing that it held hearings in 1972 and Frankie M. Freeman, the St. Louis lawyer and member of the commission, issued the report the next year: “Cairo, Ill.: A Symbol of Racial Polarization. It said: “Black residents have been faced with serious harassment and physical brutality by law enforcement officials (who) have aligned themselves with groups whose purpose is to oppose the enforcement of equal opportunity for all citizens regardless of race.”

The Civil Rights Stories Never Published

James C. Millstone was the Post-Dispatch’s Supreme Court reporter in the 1960s. Millstone covered the civil rights protests in the South. After months on the road, he returned to the home office on his way back to the Washington Bureau.

That’s when he got his first look at how the paper had handled his dispatches from the front lines of the civil rights marches. The paper had not run the stories as stand alone eyewitness accounts to history, but instead folded a few paragraphs here and there into wire service reports. Haynes Johnson, with whom Millstone had reported the stories while traveling in the South, got a Pulitzer Prize. Millstone’s stories didn’t make it to the readers.

The Post-Dispatch’s account of Rev. King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech suffered a similar fate. Reading the long story, one would never know that Dr. King’s words were making history. His famous words were buried far down in a story about the forgettable speeches of politicians and other civil rights leaders.

I became a reporter at the Post-Dispatch in the fall of 1971. Much of my reporting involved race. Municipalities had passed anti-blockbusting laws that banned for-sale signs and imposed occupancy regulations limiting how many members of a family could live together.

One St. Louisan who greeted me was Franklin V. Chesnutt, a member of the Ku Klux Klan who didn’t appreciate my stories. He telephoned me repeatedly and threatened to burn a cross on my front lawn. He even sent me his card, which listed his KKK membership.

One day in 1972 Charlie Prendergast, a beloved executive city editor, sent me out on an assignment about police brutality. As a last caution, he opened the bottom left drawer of his desk and pointed at a stack of stories.

He told me it was a big project on racism that never had made it into publication. Make sure you don’t make the same mistakes, he cautioned.

It wasn’t the only time a big racism project at the Post-Dispatch failed to make it into print. A months-long project in 1999 also never saw the light of day.

I was involved in one civil rights series that same year – an old-fashioned, editorial crusade to persuade St. Louisans to tax themselves to pay for continuation of the city-county school desegregation plan. With the help of civic leaders, such as Chancellor Emeritus William Danforth, the tax passed.

About a decade later, the online St. Louis Beacon decided to try a major project on race. Beacon representatives travelled around town to line up media partners. Many said it was a good idea but all had reasons they could not participate. One media executive said it was too soon to write about race in St. Louis.

The Beacon ended up publishing the project with the Missouri Historical Society as a partner. It was called:

Race Frankly.

Ferguson – the Citizen Activist Becomes the Citizen Journalist

Ferguson was a journalistic revolution that marked the triumph of the citizen/activist journalist over the traditional mainstream media. Gone forever was the day when an editor at the Post-Dispatch or KMOX could decide a black kid shot to death by a police officer on a Ferguson street wasn’t big news.

The first tweet reporting Michael Brown’s death was two minutes after he crashed to the pavement on Canfield Drive.

There were five million tweets in the week after Brown’s death and 35 million in the months that followed. Protesters with cell phones seized the national agenda, told the story from their points of view, knit together a new national civil rights movement and scratched the scabs off the nation’s racial scars.

Social media’s prevailing view of Ferguson – that Brown had been executed, with his hands up and shot in the back – came to dominate many media accounts.

It turned out the narrative was a myth, but one with great power and truth. No, Brown didn’t have his hands up or say ‘Don’t Shoot,” the Justice Department concluded. But, yes, Officer Darren Wilson’s escalation of his confrontation with Brown had led to the shooting. Yes, the Ferguson police were involved in grossly unconstitutional policing that victimized blacks. Yes, white police officers shoot and kill African Americans without sufficient justification all the time.

And yes, this land of Dred Scott has never directly confronted its racial demons.

12:03 p.m. “Just saw someone die OMFG.”

The first tweet about the death of Michael Brown was a minute or two after he collapsed on Canfield Dr., just past noon Aug. 9, 2014. Local rapper Emanuel Freeman (@ TheePharaoh) tweeted from inside his home a photo of Brown’s body face down in the street, an officer standing over him.

12:03 p.m. “Just saw someone die OMFG.”

12:03 p.m. “I’m about to hyperventilate.”

12:04 p.m. “the police just shot someone dead in front of my crib yo.”

Forty minutes later, at 12:48 p.m., a previously unknown young woman, La’Toya Cash, joined the conversation. She posted this tweet as @AyoMissDarkSkin: “Ferguson police just executed an unarmed 17-year-old boy that was walking to the store. Shot him 10 times smh.”

The account of the “boy” “executed” walking on the street and shot 10 times established Mike Brown’s victimhood. smh – Twitter speak for“shaking my head,” – drove home the point, as did a photo showing dozens of police cars in the street.

The tweet was retweeted 3,500 times in the next few hours as word of the shooting passed through the community like an electrical charge. @AyoMissDarkSkin’s report received much more attention than the Post-Dispatch’s report hours later.

Never before in America had a story exploded so fast from the people who normally feel disenfranchised.

Even though the Twitter story had big mistakes, it told the essential truth about white police officers killing black suspects. And it connected people into groups that led to reforms, says Nicole Hudson, now a vice chancellor at Washington University who led the Forward Through Ferguson reform effort.

“As much as people pooh-pooh social media as a horrible loud place,” she said, “there are moments and times when real community is created and change can happen….There is this myth that Twitter is horrible because there is a bunch of untrue stuff on it but like any medium you have a responsibility to use your brain.”

Hudson said she was disappointed with traditional media’s coverage. “The thing I found frustrating in the traditional media is I wanted to see a story about the nuances to the protest movement. I wanted to see a story that recognized what was happening on the ground between the young kids and the elders and that some of the elders were having some aha moments about how the kids were saying you’re not my elder and I don’t need to listen to you.”

An Awakening

Traditional media played an important part, though, in memorializing the Ferguson protest through the photos of the Post-Dispatch photo staff. And Tony Messenger, the deputy editorial editor turned columnist, has crusaded ever since for municipal court, bail, board-bill and police accountability reforms.

For Messenger and some other journalists, Ferguson was an awakening. Richard Weiss, whose Covid and Clayton stories appear in this issue, was another journalist for whom Ferguson was a turning point.

St. Louis Public Radio devoted the entire staff to Ferguson reporting, curating a live blog to keep up with the rapid news developments and launching the “We Live Here” podcast on race and class. “We Live Here” brought alive historical events such as the landmark restrictive covenant case of Shelley v. Kraemer by interviewing descendants of J.D. and Ethel Shelley’s family about housing discrimination.

Messenger remembers that at the start of the Ferguson protests he was shocked by what he saw on the streets, turned on his tape recorder and said, “This is not St. Louis.”

After Ferguson and after Charlottesville, Messenger realized he was wrong. After watching Nazis march through the streets of Charlottesville with torches he tweeted, “This cannot be the new normal in America.”

Jason Purnell, the Brown School professor at Washington University, who had pulled together the ground-breaking For Sake of All report, tweeted back. “America isn’t better than this. America is this. America CAN be better than this if we can finally face that fact.”

Messenger realized he was wrong. He wrote:

“When the president of the United States, Donald Trump, can’t even bring himself to condemn such God-awful displays of racism and outright treason on American soil, this is not something that can be written off to ‘extremists’ or a broken political system. This is America. It’s an America that allowed Republicans to gut voting rights protections so that black voters would have a more difficult time voting on election day. It’s an America in which a black lawyer in Jefferson City is not allowed to testify against a bill that makes it easier to discriminate in Missouri against people of color because a white Republican doesn’t want to be bothered by talk of the long-past ‘Jim Crow’ era. It is an America in which white elected officials in both parties, and their donors and alumni, brought the University of Missouri to heel after black students and faculty stood up for their rights, and demanded change.

“Charlottesville is America. For far too many Americans, we are not better than this, and we never have been. The arc of American history has much more bending to do before justice even enters the frame.”

William H. Freivogel is the publisher of Gateway Journalism Review. This story will be published in the spring 2020 print issue of the magazine.

GJR’s special issue on the history of slavery, segregation, and racism in our region was produced with the help and financial support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.