In the late 19th century, Canada began its residential schools program—a violent system that aimed to decimate the cultures of indigenous people.

The system mimicked what the U.S. had done just several decades earlier, when it built schools outside of Native American reservations to forcibly assimilate indigenous people.

Children were kidnapped and brought to live at schools across Canada, which were often operated by churches. They were punished for speaking their native language, separated from siblings and forced to do unpaid labor for the facilities. Some students were physically and sexually abused and their health ailments were often neglected. A government medical inspector noted in 1907 that "24 percent of previously healthy Aboriginal children across Canada were dying in residential schools," and this number did not account for children who died after returning home, according to the University of British Columbia.

The last residential school in Canada did not close until 1996.

Nine years later, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a formal apology to survivors of the schools, saying that "we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country." In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which the Canadian government established to investigate this history, called the residential schools an attempt at "cultural genocide" within Canada.

"These measures were part of a coherent policy to eliminate Aboriginal people as distinct peoples and to assimilate them into the Canadian mainstream against their will," the report stated.

Photographer Daniella Zalcman has photographed this legacy in a series of portraits and interviews with survivors for a project supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. For many of them, this marked the first time they had spoken about their experience in the schools. She spoke with the PBS NewsHour Weekend about the project, which was recently released as a book.

Have you done any research on indigenous Canadians before?

What brought me to Canada to begin with was I had been at the international AIDS conference in [Melbourne] in 2014 for a completely different project that I worked on for several years on the rise of homophobia and anti-gay legislation in Uganda. And while I was there, I read a U.N. report about how one of the demographics with the fastest growing rates of HIV in the world was First Nations Canadians.

And that made absolutely no sense to me from a public health perspective. Canada has an incredible health care system; they pioneered harm reduction strategies like free needle exchanges and safe injection sites and all these things that are meant to reduce health crises, and yet there is this massive epidemic and this group of people being completely left behind. So I spent a month in 2014 driving through British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Ontario. And almost every single HIV-positive First Nations person, almost all of them, referenced residential schools. And I'd never heard of residential school; it's not something that's really part of mainstream U.S. history curriculum. It's only barely becoming part of mainstream Canadian curriculum as we speak. So to me, it became obvious that the public health crises and all these other systemic issues that First Nations Canadians deal with are part of this much bigger legacy of coercive assimilation.

How did the project begin from there?

I spent that month largely focused on documenting the HIV aspect of the story. I came home with a lot of images of people dealing with drug addiction and injection drug use, the primary means through which HIV is spread in First Nations communities in Canada. And I got home and realized that I'd kind of failed. I was starting to realize this was part of a bigger story, but I'd photographed it in this very two-dimensional way. And even though I was accurately representing what is reality for many indigenous communities in Canada, they were still images that were really going to do much more to stigmatize the population than they were to shine a light, than they were going to shine a light on this much bigger, largely undiscussed issue, touching on settler colonialism and intergenerational trauma. So I decided that I actually needed to go back. All of my work on this project has been funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in D.C.

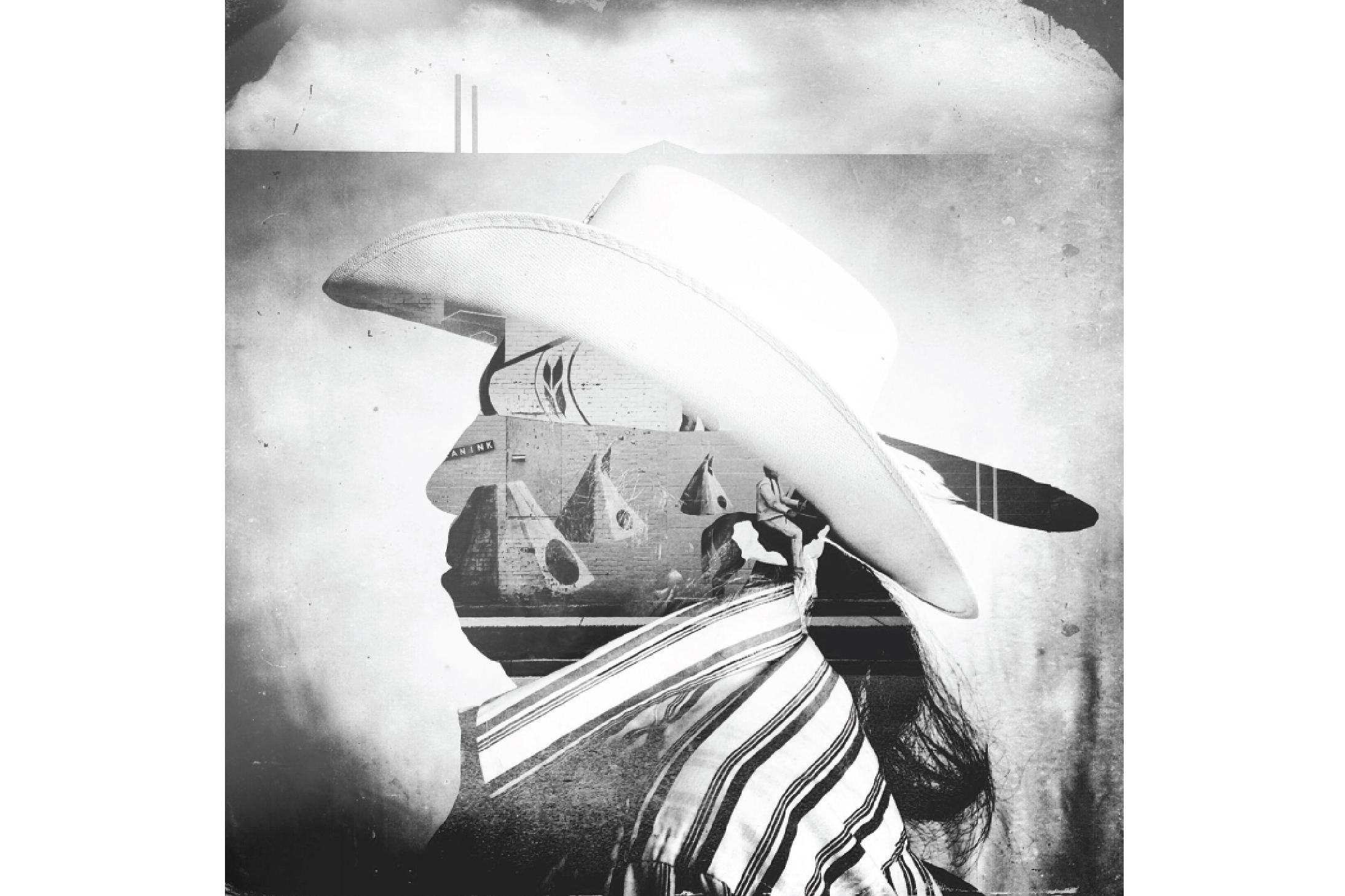

So a year later I went back and I focused on Saskatchewan, which is the province that is home to the last residential school to close in Canada in 1996, and to some of the most infamous schools in the country. I spent two weeks focused just on interviewing residential school survivors and making those multiple exposure portraits, which to me was the most truthful way to tell this story.

I can't photograph in the schools anymore because the last one closed in the '90s. I tried to photograph the visual legacy, and that, to me, had been very reductive and unsuccessful. So it became about figuring out how do you photograph memory? How do you photograph the things that we pass from parent to child? Each multiple-exposure portrait is a photo of a survivor combined with an image that is directly related to their memory of residential school.

How did you meet the subjects of these photos?

When I returned to Saskatchewan, I'd been there the year before. Most of the work I did was in Regina. And there's a neighborhood in Regina, North Central, that's kind of [known] in Canada to be the worst for crime, injection drug use, for alcoholism. And so I spent quite a bit of time there staying with and photographing one particular family. And the daughter was actually my main point of entry. She was HIV-positive, had Hepatitis C, was an injection drug user and sex worker. She herself hadn't gone to residential school, but both her parents, all four of her grandparents, and all of her aunts and uncles had gone.

You think about history and trauma and how they affect populations, but we forget that we pass those things on as well. The first person I interviewed was her aunt. I knew her, and she remembered me, and then from there, every single person I talked to would then say, "Oh, well you should talk to my neighbor, my cousin, my friend." One survivor would introduce me to the next.

Was it difficult for survivors to describe their memories?

I expected to be rebuffed by half of the people I approached. And I was surprised that almost everyone I spoke to was very willing to talk to me, to be interviewed on the record. I think part of that is because Canada had recently gone through this Truth and Reconciliation Commission. When I was there in 2015 [it] was at the very end of it.

I think people had to give testimony in order to be part of the TRC, so this was something, even though that had been the first time for many people in their lives that they had discussed what had happened to them in residential school, it was something that was starting to come out into the open. So I think that helped facilitate a lot of my conversations. But even then. I still had a lot of people disclose to me for the first time ever a lot of assault and trauma and abuse.

It continues to be shocking to me that this institution that lasted for 120 years in Canada remains so under-discussed. And I think for a lot of people, the idea that someone actually was interested and wanted to listen was enough that it made them really want to share.

How did you structure your sessions with the survivors?

We would speak first, and I told people, we can speak for as little or as much as you would like. On average, I would say the interviews were about an hour to two hours. And then after that I would photograph every single person against a white backdrop, and then on my own would go in search of a second image. Sometimes they were the actual sites of where the school was, the actual building where they had lived, and then sometimes they were a little more figurative, depending on memory, and most of these buildings have been torn down now in Canada, so there isn't always physical evidence of each school. But it was something that was still evocative of our conversation.

How did you produce these images?

I shot the entire project both on medium format film and on my iPhone. I actually use my phone a lot in my work, and because while I was interviewing I was on the road for two weeks, I really didn't want to wait to get home to develop my film and start thinking about how to make multiple exposures. So all the work you've seen is actually shot and edited on an iPhone. There's just a very simple app I use call Image Blender that just allows you to create multiple exposures.

Why did you decide to stylize the photos in this way, with overlaid images? How did that contribute to what you were exploring in this project?

We're already institutionally not very aware of or willing to speak to the legacy of colonialism in North America. We don't frame it in that way. Generally speaking, we have excluded much of that narrative from our history books, from mainstream media. Trying to get people to think about how the repercussions of those events remain with Native communities today, are still deeply impacting their lives, I think is usually important. And so that's what I'm attempting to do with these images.