To view the interactive graphics in this report, click here.

A powerful machine has cranked up in North Carolina. Quiet at first, it’s now hard to ignore. On the surface it looks simple. But underneath it’s more complex.

From the rubble of the Great Recession, well-funded investors began amassing single-family homes and renting them out.

These companies are more than just landlords. They are optimized and efficient, equipped to squeeze profit out of houses.

These giant firms have bought up tens of thousands of homes in North Carolina. Their impacts are growing. And they could extend for generations.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

This is how Wall Street built a machine to buy the American Dream.

As houses go, the one at 4053 Laurel Glen Drive in Raleigh isn't especially remarkable.

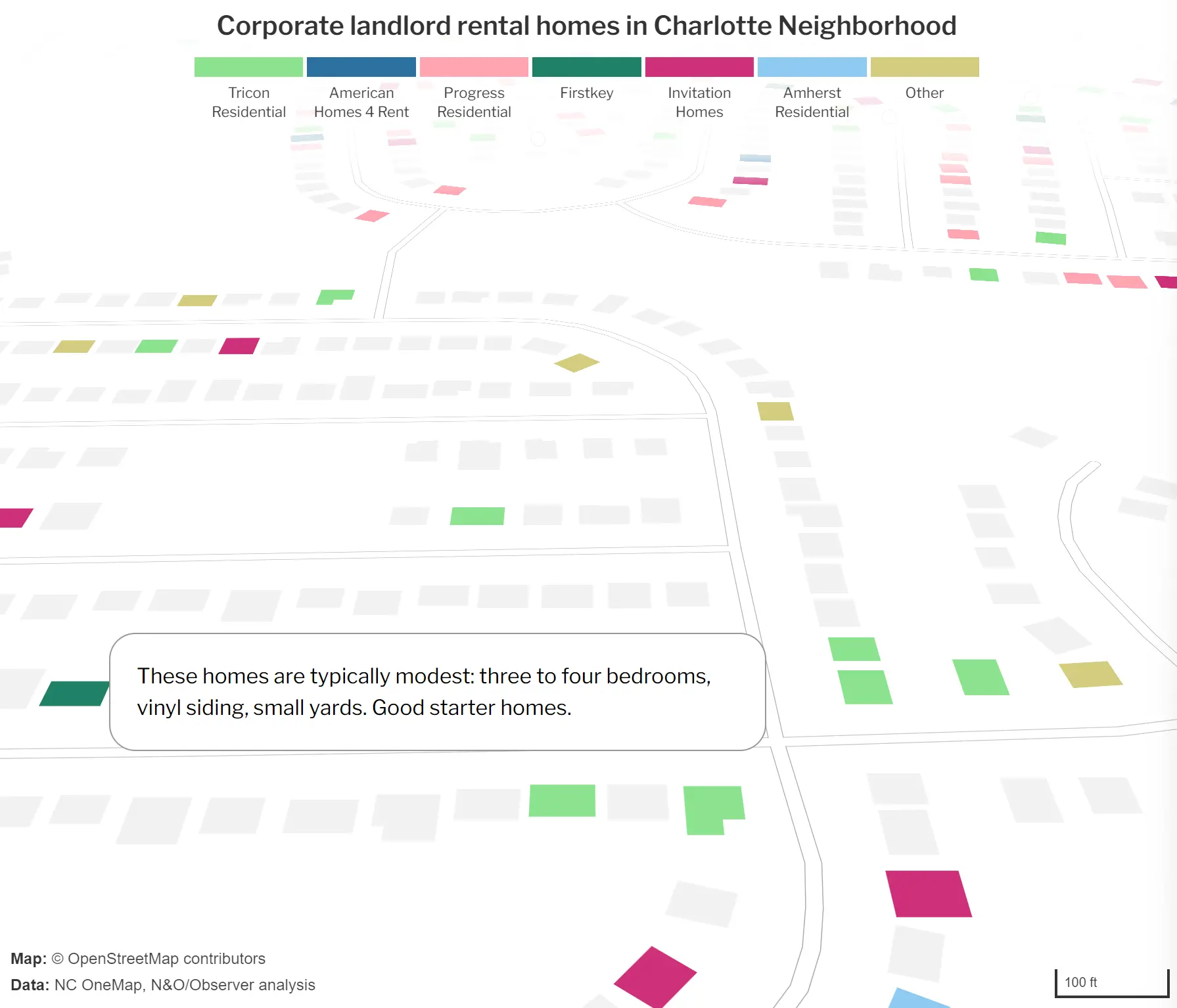

Clad in tan vinyl siding, the three-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bath is typical of single-family homes built in the early-2000s subdivisions along the outskirts of North Carolina cities. But when the property went on the market on a Tuesday night in mid-March, it wasn't long before the offers came rolling in.

It didn't matter that the owners weren’t ready to show it. Or that the only photo on the "coming soon" listing was a single exterior image taken when the house was built about 15 years ago.

Raleigh Realtor Brittany Jones got the first offer by email around dinnertime the next day. The second came less than an hour later. A third arrived that night, about 24 hours after she posted the property for sale.

The buyers had a lot in common. They offered all cash and bids well over the $330,000 list price. They'd take the property as is. And all three had out-of-state addresses with obscure names marked with abbreviations and numerals — like "MCH SFR NC Owner 3 LP" and "IH 6 Property North Carolina LP."

Jones has seen names like these plenty of times in her three years selling Triangle real estate, which like Charlotte is now a hotbed for such buyers.

Agents don't say much about their clients. But they make it clear they have money in the bank.

"When you relay that to a client, that's all they want to know," Jones said.

When they wrapped up negotiations days later, the new owner wasn't a person. It was a corporation called SFR JV-2 PROPERTY LLC, which paid about $18,000 over asking.

Officially established in North Carolina just last June, the company has been busy. It now owns more than 100 homes in the Triangle as of early April. In the Charlotte area, it owns another 350.

But SFR JV-2 isn't really a company. Not in the traditional sense. It's a subsidiary of a massive, publicly traded firm called Tricon Residential.

Tricon is one of the investment corporations, shored up by mountains of Wall Street cash, that have amassed hundreds of thousands of properties across the country, transforming these new rental properties into profit generators.

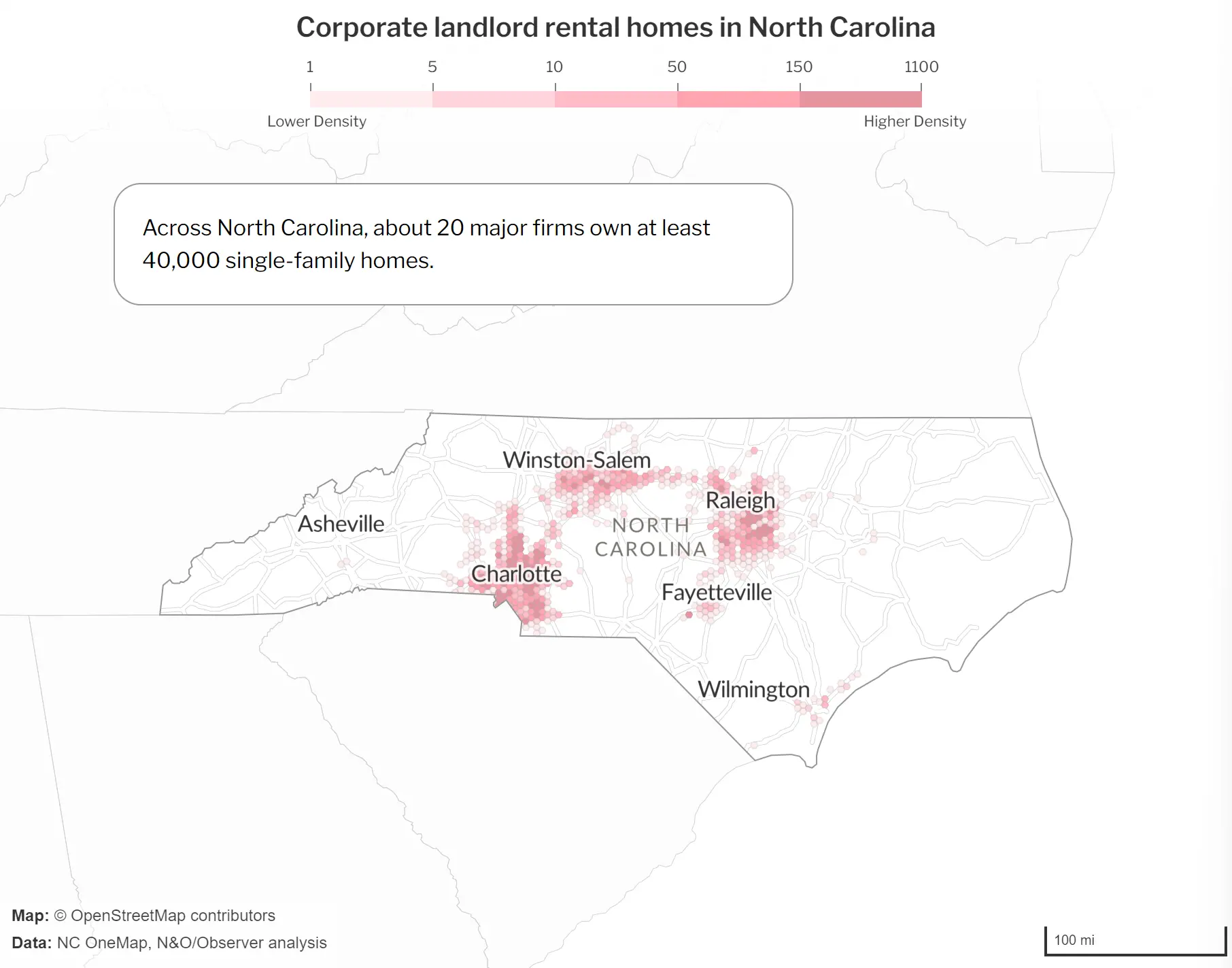

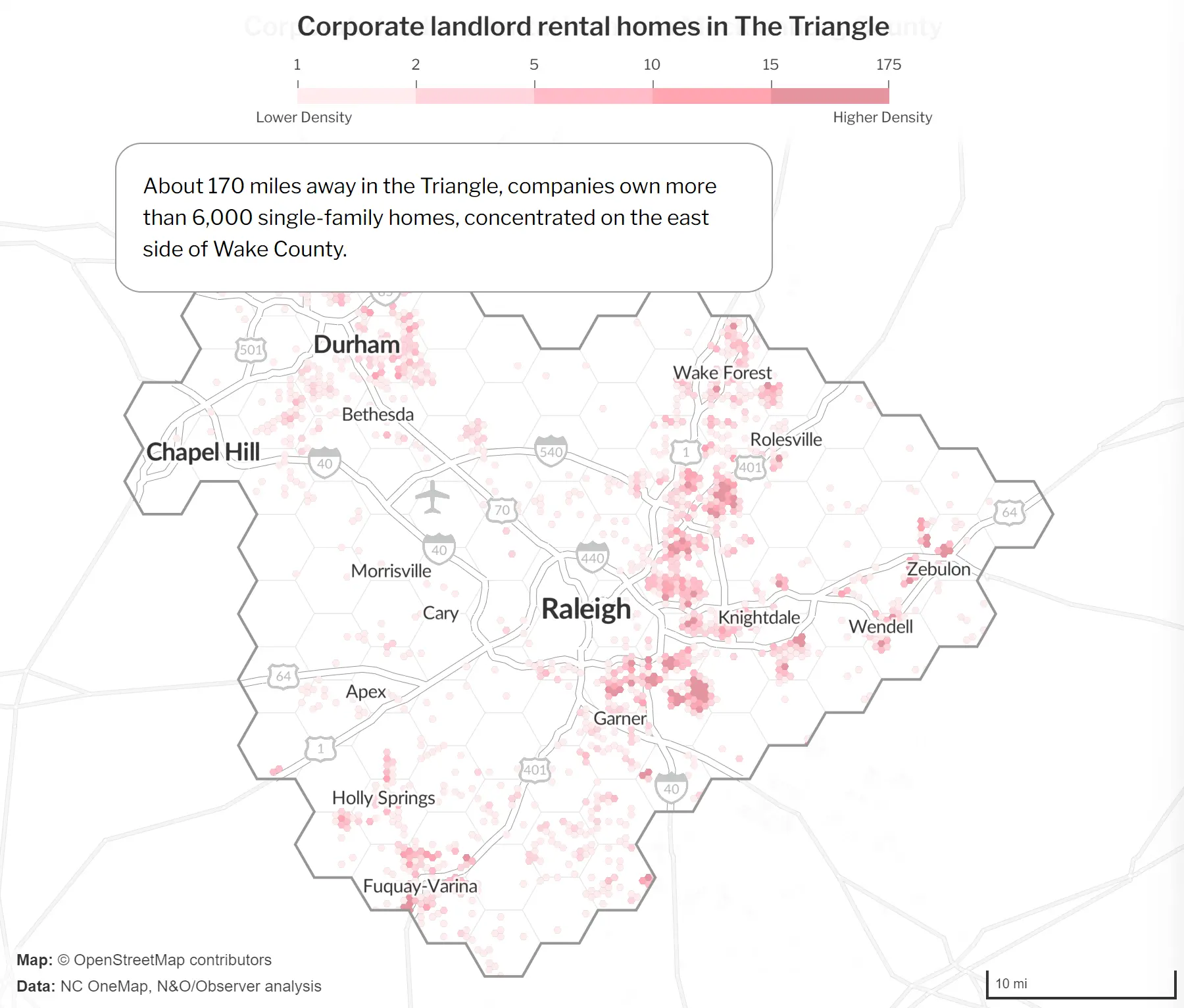

A monthslong investigation by The News & Observer and The Charlotte Observer has revealed, for the first time, the scale and scope of these purchases across North Carolina. At least 40,000 single-family properties are now held by about 20 companies.

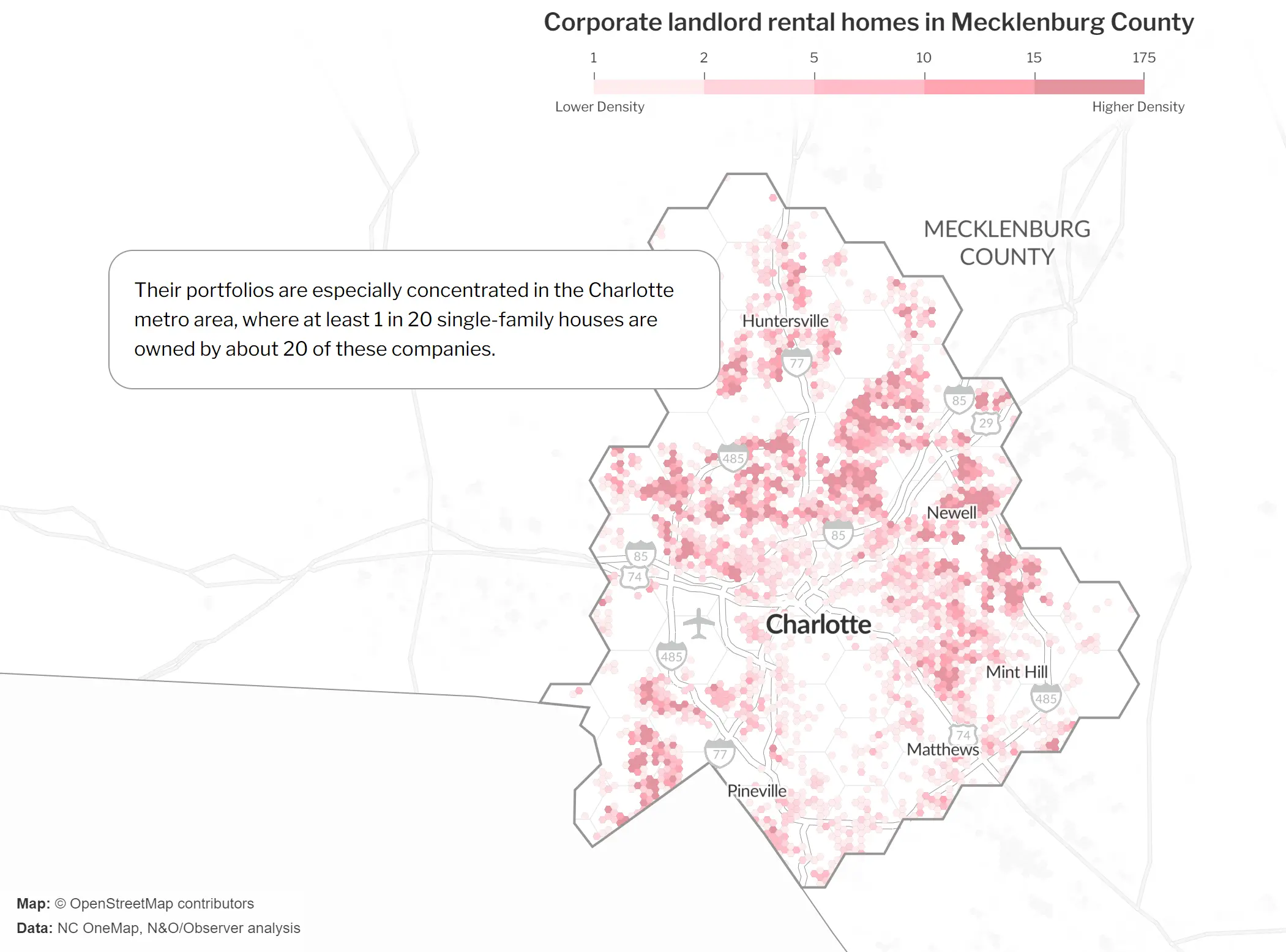

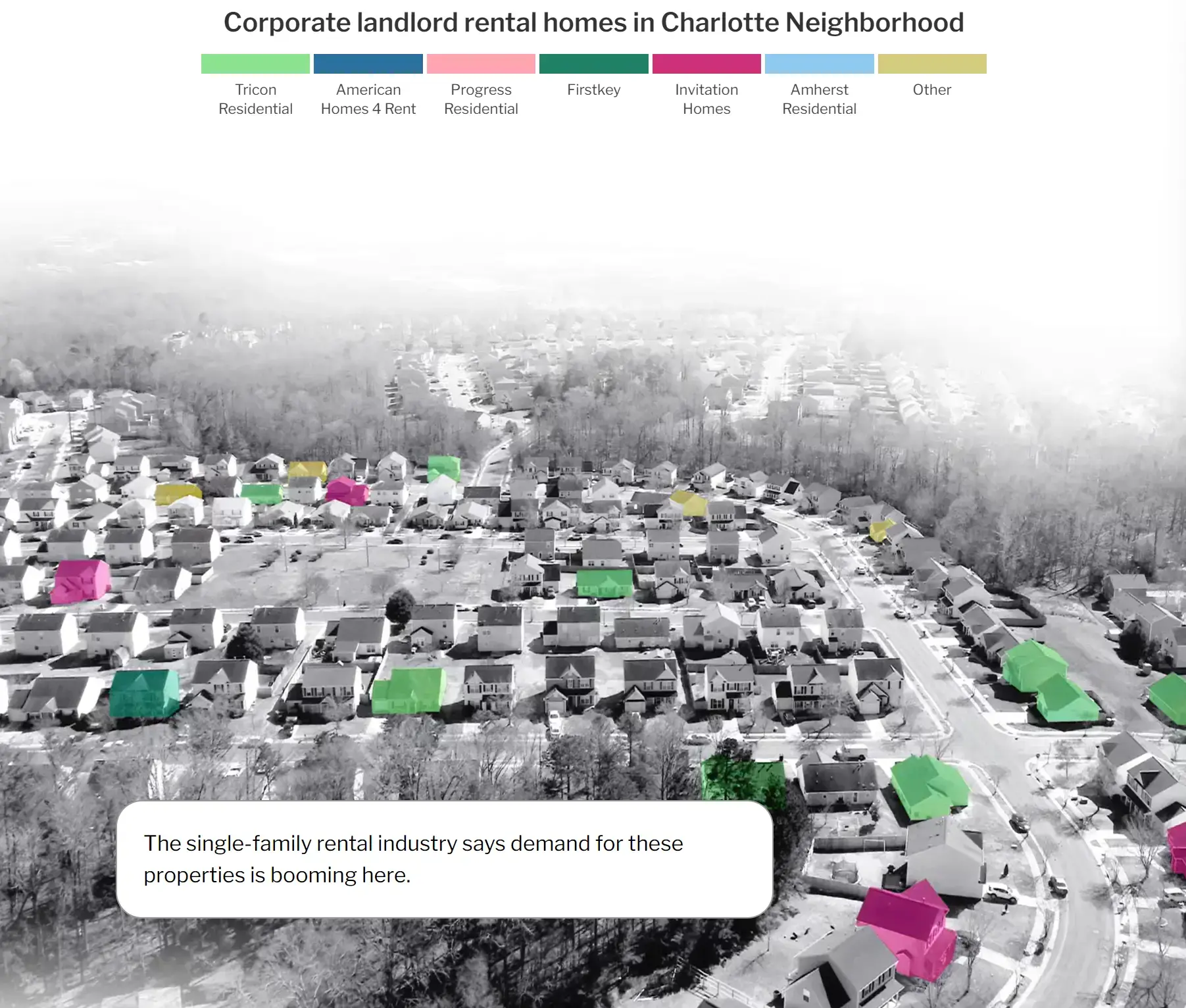

Nowhere is that consolidation more evident than in Charlotte — these firms now own one-quarter of all the rental houses in Mecklenburg County.

This is a business primed for continued growth, one dependent on gobbling up and building even more single-family homes, traditionally the cornerstone of financial security for most American families.

The industry is simply meeting a market demand, said David Howard, executive director of the National Rental Home Council, the trade association that represents some of the largest corporate single-family rental firms across the country.

"Historically, let's face it: when it comes to housing, there have been two options. You can buy a single-family home or you can rent an apartment," Howard said. "What our member companies are doing are coming in and saying, 'Look, you have a third option.'"

But many think it’s a move for the worse.

Would-be homebuyers say it is increasingly tough to compete with the industry’s nimble and well-funded purchasing machinery.

Some tenants complain about slow and shoddy maintenance, steadily rising rents and fees that wring profit from them. Communities are beginning to turn to government leaders to curb these companies' growth.

But 10 years after investor landlords began their rise here, local officials are only starting to understand their scale and impact. So far at least, they haven’t intervened.

All of this leaves some real estate experts, prospective homeowners, public officials — even renters themselves — dreading what may happen if corporations keep buying up the block.

But Charlotte's not alone.

On a sunny afternoon in January, about 170 miles away from the house on Laurel Glen, Jonathan Osman brought his Jeep Grand Cherokee to a stop on the 6300 block of Downfield Wood Drive in the Highland Creek neighborhood of northeast Charlotte. When he pulled out his iPad, the screen lit up with a map of real estate listings.

To his left sat a two-story, 2,000-square-foot home built in 1995. Osman, who's been selling homes in Charlotte for nearly two decades, could see from his tablet that a married couple bought it about a week before Christmas for $370,000.

As he swiped his fingers across the screen, he pulled up a listing for a home just down the block. This one was also built in 1995. It also had 2,000 square feet across two stories, like so many others on the street.

But when it sold just six years ago for $172,000, the new owner was a subsidiary of Invitation Homes, now the nation's largest single-family rental company.

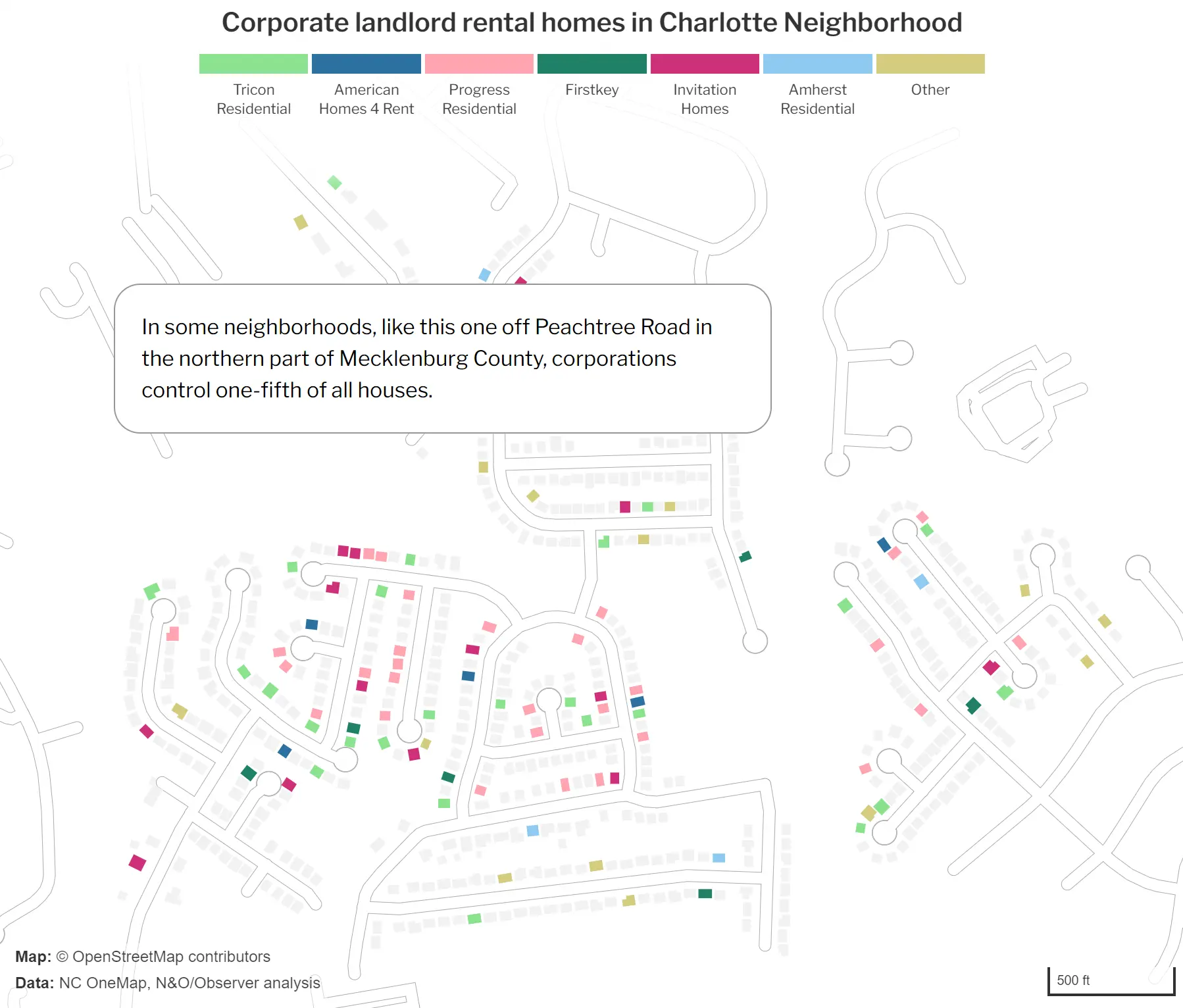

The corporation owns three other homes on the block in Highland Creek, according to the N&O and Observer's analysis. In all, Invitation and three other single-family rental companies — American Homes 4 Rent, FirstKey and Amherst Residential — own eight homes among the dozens on Downfield Wood Drive.

For years, Osman has watched these companies buy homes across Charlotte.

After the housing crisis that began in 2008, he said the purchases came as welcome news. No one was buying homes back then. Plus, Osman and others figured the firms would sell off the properties after five to seven years.

That never happened.

Now, on a street like Downfield Wood Drive, Osman can paint a picture of the buying spree in Charlotte, where millions of dollars in equity that could be in local residents’ hands now sits with corporations.

“The number-one way we transfer wealth and accumulate wealth is through real estate ownership,” Osman said. “There’s equity that is going to corporations that could have been going to people.”

Zoom out from the one block in Highland Creek and you’ll find clusters of investor-owned homes across the region. In Charlotte and its outlying communities, investors own more than 25,000 homes across Mecklenburg, Union, Cabarrus, Iredell and Gaston counties.

The investors have even found their way into Osman’s own neighborhood, in a subdivision across town.

The seller he represented there eventually sold in November to Invitation Homes, which offered $330,000 — nearly 12% above asking.

"The number-one way we transfer wealth and accumulate wealth is through real estate ownership. There’s equity that is going to corporations that could have been going to people."

-JONATHAN OSMAN, CHARLOTTE REALTOR

Osman found listings on websites like Zillow and Realtor.com that listed the rent at $2,350 a month.

That rent could pay for a $450,000 mortgage, way above what the company paid, he said.

That’s frustrating to Osman. For years he’s worked to make people aware of the negative impact single-family rental companies could have on the Charlotte area housing market. That includes higher rents and inflated home prices, a direct outcome of the number of would-be buyers exceeding the number of homes for sale.

But, for people selling a home, it can be hard to walk away from a high bid.

The extra $30,000 or $40,000 that comes with an investor offer could be money sellers need to battle it out in this red-hot market to get another home.

“They see it as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Osman said.

Despite deep concerns by Osman and others, corporate landlords are well positioned to keep snapping up homes in North Carolina.

One big reason: a money machine carefully engineered in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis.

Banks and others have long sold "asset-backed securities" that promise buyers slices of profits down the road. The exact asset in that asset-backed security can vary.

In the late 1990s, rock icon David Bowie securitized his music catalog, selling his songs' subsequent royalties. So-called "Bowie bonds" earned the artist $55 million, according to the BBC.

Mortgage-backed securities take the same approach to home loans, bundling them up with the promise of future house payments. But those securities doomed the housing market ahead of the Great Recession when millions of borrowers defaulted on their loans.

Facing the sheer magnitude of so many foreclosed homes, the Federal Housing Finance Agency in 2012 allowed investors to scoop up pools of those properties in some of the hardest-hit U.S. cities and rent them out.

In 2013, financiers used those same properties to invent a wholly new security — this time backed by rental payments.

"If these are decent properties and they're well maintained, they can continue generating income for the foreseeable future," said N.C. State finance professor Richard Warr. "So that's a much simpler product than a mortgage product."

Making a Rental-Backed Security

Step 1: Amherst Residential acquires a large number of single-family homes and starts renting them out.

Step 2: Amherst forms a subsidiary called Alto Asset Company 4 LLC, where it will hold the deeds to about 1,700 of its rental houses across 14 states, including North Carolina.

Step 3: Amherst goes to Goldman Sachs for a loan that’s backed by the houses held by Alto Asset Company 4 LLC.

Step 4: Goldman issues a $364 million loan. This deal creates a trust, called AMSR 2021-SFR 3, which will issue bonds used to repay the loan.

Step 5: The trust then divides this security into smaller pieces, or tranches, to sell to investors. Higher-rated tranches are paid first, but have a lower rate of return. Lower-rated tranches are paid last, but because they’re cheaper, they have a higher potential return rate.

Step 6: Large-scale investors, including the North Carolina state employees’ pension fund, buy the bonds.

Step 7: The collective rent payments of the 1,700 homes go to pay bond holders and bank fees.

Step 8: Amherst can use the $364 million loan to buy thousands of additional single-family homes to rent, which it can then use to create more rental-backed securities.

Selling securities gives corporate investors large sums immediately, which they can plow into buying more homes.

Howard said the use of these bonds isn’t unique to the single-family rental industry and “reflects commonly accepted practice” in real estate.

But Elora Raymond, assistant professor of city and regional planning at Georgia Tech, says it's this infusion of funding that not only fueled the rise of the single-family rental industry, but made building rental empires attractive to investors in the first place.

"The securitization — they never would have done it without that," said Raymond, who studied the impacts of corporate landlords as a researcher for the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. "It's the ability to access cheap capital and keep replicating this business that makes it worth their while."

Not all players in the single-family rental industry use rental-backed securities to raise funds.

But in the 10 years since they got their start, Invitation and other companies — Amherst Residential, American Homes 4 Rent and Progress Residential included — have sold more than 100 of these securities for billions of dollars through banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

To view the interactive graphics in this report, click here.

They're safe enough investments to attract massive pension funds for state and local government workers across the country, including the North Carolina Retirement System, which manages investments for nearly 1 million current and retired public employees.

As of the end of 2021, the latest data available, the state owned $20.1 million worth of assets in seven different rental backed-securities, just a fraction of a percentage of the fund’s $115.2 billion in holdings.

But the nature of those investments isn't always obvious — even to the state treasury's senior leadership.

Every penny tied up in rental-backed securities is beyond the state's control, part of a much larger portfolio managed independently by an outside firm. Once the pension invests with managed funds like these, State Treasurer Dale Folwell said, "we're just a passenger."

"I try to be fluent in all types of sayings and acronyms. I've never heard the term 'rental-backed security' until just now," Folwell said, in an interview with the N&O and Observer in April.

The retirement fund has another $58 million invested in single-family rental companies like Tricon and American Homes 4 Rent. Only one investment — $2 million worth of assets sunk into Invitation Homes — was a direct decision by the treasurer’s staff.

Rental-backed securities, in particular, have been good for the state pension, earning the retirement fund a 3 to 4% return annually.

But what's less clear is whether they're good for the North Carolina tenants fueling those profits with every rent check.

Tenants like 23-year-old Madison Swope.

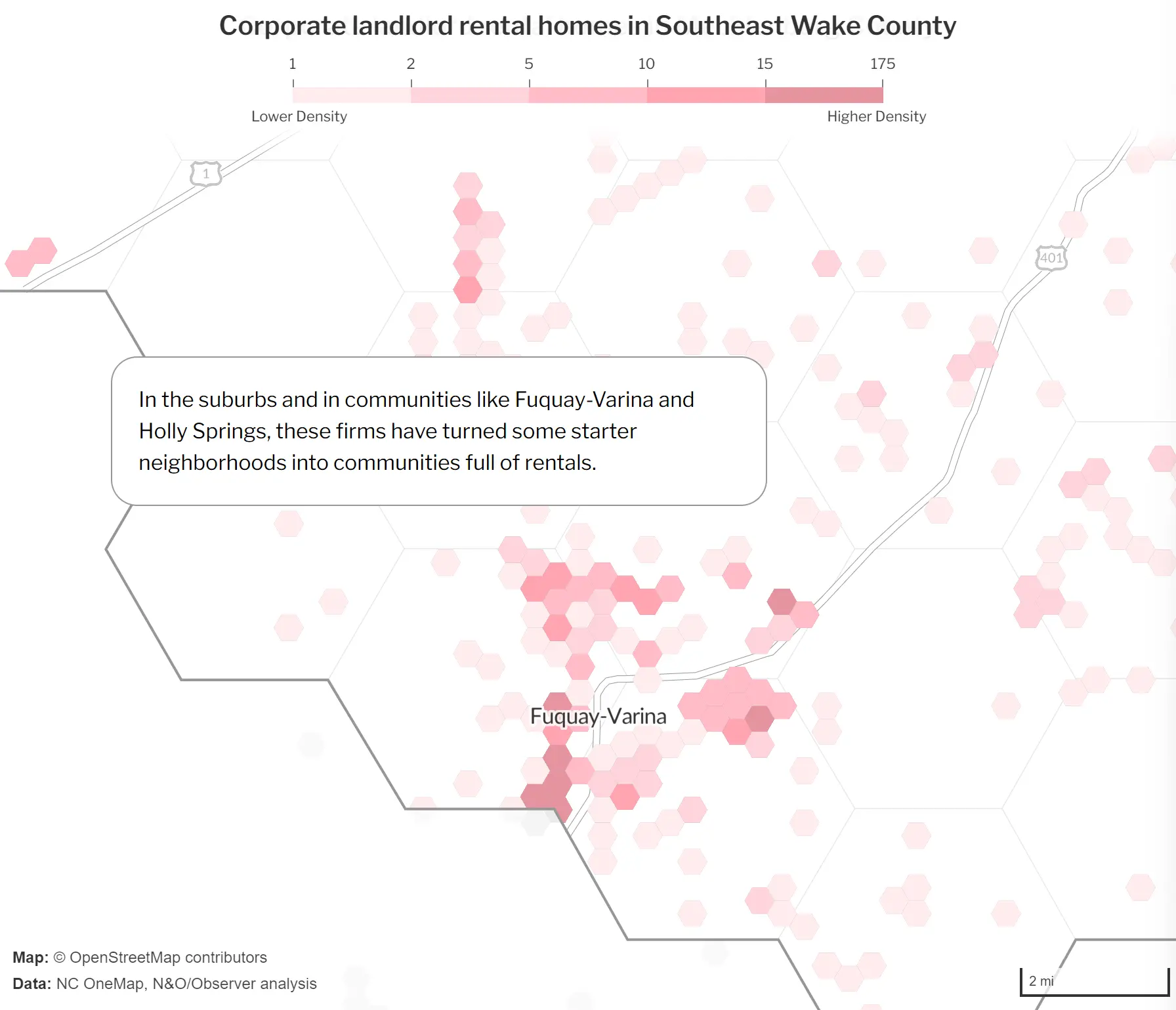

The house on Scofield Drive in Raleigh where Swope and her fiance live with their roommate is owned by Amherst Residential, a private equity firm actively buying across the state.

Deed records show the address was securitized with dozens of other properties in Wake and Mecklenburg counties — and another 2,700 across the country. In exchange for paying others that future rental income, Amherst earned about $500 million in the summer of 2020, according to the credit rating agency Moody’s.

Swope, who works in sales, moved to this three-bedroom, two-bath home from a Garner apartment last June, renting from Amherst's management entity, Main Street Renewal.

A modest 1,300 square feet with laminate hardwood flooring and enough room for the household's two dogs, she loved the house the moment she saw it. She still loves it, in fact.

The rent is slated to go up this year — $1,530 compared to $1,395 when they first moved in. But she said the cost would be higher if they weren't existing tenants.

Like thousands of others who have migrated to the Triangle and Charlotte in recent years, they want to be in a house near a city.

That demand is one of the reasons why occupancy rates at corporate-owned, single-family rentals in Charlotte and Raleigh are the highest in the country at about 98%, according to Howard.

"Why should it be the case that the only people who can live in those neighborhoods are the people who can afford to buy, who have the wealth and the circumstances to come up with a 20% down payment and to purchase a home in those neighborhoods?" Howard said.

For many renters, Howard said, homeownership isn't the best option. And Americans in general are becoming more comfortable with renting.

"Nobody thinks twice about the fact that you have a leased car in your driveway. I have a daughter in college, she rents dresses to go to parties," Howard said. "Renting and leasing is becoming a part of the culture."

But owning a home is different, said Georgia Tech's Raymond. It's still a fundamental building block to both financial security and generational wealth for the American middle class.

"Homeownership has increasingly become the cornerstone of the American dream as wages have eroded. You can make money off of housing wealth. You can retire on that, right? When you retire, you sell your home, you downsize, that's a big part of your nest egg," Raymond said.

"You used to have a pension for that. This replaces the pension. This replaces the high income job that you used to have. And now that's going away," Raymond added.

Home equity accounts for about one-third of the household wealth for the typical American, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And losing it, Raymond said, could cause ripple effects that last for generations.

Swope has been mostly happy with her rental experience, even though it carries some uncertainty.

"They could not offer to renew, right? There's no reason they wouldn't for us, but what if they did? Or what if they decided to sell?" Swope said. "It does make you kind of insecure. Like, well, I guess we'll rent forever and pay double what we would on a mortgage."

She doesn't want to rent forever.

She's getting married in October, and they'd buy their current house if Amherst would be willing to sell it.

But she also knows the neighborhood — and how ubiquitous single-family rental companies are on the block. Amherst owns a house across the street, and another two doors down. Her neighbor's property is owned by Progress Residential, another major player in the market.

"I like this area enough to buy a house here, but I probably can't," Swope said. "Because they own it."

All told, the N&O and Observer analysis shows, large corporate landlords own at least 40,000 properties purchased largely over the last decade across the state, with no sign of their buying slowing down.

The vast majority of those homes are in the hands of hundreds of subsidiaries that the newspapers’ reporting traced to about 20 major firms through mailing addresses and corporation paperwork.

Some of that corporate control is murky — seemingly unconnected firms sometimes share mailing addresses with major home rental companies, and several businesses have merged or spun off over the years.

Given the complexities of these companies’ ownership structures, this best count to date is likely a conservative estimate, said David Szakonyi, an assistant professor of political science at Georgetown University who reviewed the N&O and Observer’s findings.

"American real estate, historically, has been owned by individuals and families. We're seeing hints that the whole state of play is changing,” said Szakonyi. He co-founded the Anti-Corruption Data Collective, a research and advocacy group. It began examining how money flows through the private investment and real estate market in 2021.

“Having a number about how active these investors are helps us to understand in what direction that trend is going and how big of an issue this potentially is," he said.

The current and potential scale of corporate ownership concerns some experts who have watched the rise of the industry over the past 10 years.

“It definitely raises questions about monopolization and the ways they’re able to alter the logic of the market,” said Desiree Fields, assistant professor of geography and global metropolitan studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Howard calls such assessments "absurd." He's seen no data to show that the presence of single-family rental homes have had detrimental impacts on the market or that they're pricing out regular homebuyers in a "pervasive, systemic" way, he said.

"I like this area enough to buy a house here, but I probably can't. Because they own it."

— MADISON SWOPE, AMHERST RESIDENTIAL TENANT

And these companies are increasing housing stock by constructing new homes in "build-to-rent" communities: American Homes 4 Rent, which has the biggest rental footprint in the state with more than 8,000 properties, says it’s the nation’s 45th largest homebuilder.

"Housing markets are not monolithic. And they're not controlled by a monopoly, an oligarchy, of companies or individuals," Howard said. "There's too much happening in those markets."

And although the industry is still poised for more growth, he said it would take a lot more than the 15,000 homes they own in Mecklenburg County — which counts about 275,000 total — to start causing problems.

"I mean, look, if it got to the point where anybody had any level of concentration, whereby they were purchasing 100% of the housing stock, then yeah, that could be an issue," Howard said. "We are nowhere near that point."

He also bristled at the notion that these companies extract wealth from neighborhoods. Companies often pour thousands into renovations before renting out newly purchased homes to tenants for the first time, he said.

These companies, Georgia Tech's Raymond said, are doing what they're built to do: make money. But in an environment with very few protections for tenants, renting from them can be a bad deal.

"Housing is a basic need," she said. "And we've completely commodified it."

As for the property on Laurel Glen in Raleigh — the one that sparked three offers, sight unseen — Tricon Residential posted a rental listing for the property within days of closing.

The sellers weren't out yet. They were still packing for the move — one of the perks of the deal was that they could stay another two weeks for free while they wrapped up the details on their next home.

The rental posting had no photos. Just the basics about bedrooms, bathrooms and square footage.

A typical renter in this neighborhood in eastern Wake County pays about $1,300 a month for a three-bedroom home, according to 2020 census data. Monthly housing costs — mortgage payments, utilities, insurance and the like — are about the same amount for the typical homeowner here.

But on May 19, one month after the departure of the only owners the home on Laurel Glen has ever had, there's likely to be a new tenant in place.

Their rent, not including utilities: $1,849 a month.

Read more Security for Sale day-one stories, on how to detect corporate landlords when rental shopping, how real estate investing is changing a Concord NC neighborhood once again and what all that real estate investment jargon really means.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Security for Sale was reported and written by investigative reporters Payton Guion of The Charlotte Observer and Tyler Dukes of The News & Observer, with significant contributions from Observer growth reporter Gordon Rago. Additional reporting by News & Observer real estate reporter Mary Helen Moore. | Art direction and animation by Sohail Al-Jamea | Illustrations by Rachel Handley | Design, development & interactive maps by David Newcomb | Photos, drone footage and videos by McClatchy visual journalists Jeff Siner, Khadejeh Nikouye, Melissa Rodriguez, Travis Long, Julia Wall, Alex Slitz, Loumay Alesali, The' Pham and Scott Sharpe. | Edited by Cathy Clabby, McClatchy Southeast investigations editor, and Adam Bell, Observer business and arts editor. | A special thanks to the Pulitzer Center, which supported this project with a data journalism grant.

METHODOLOGY

To count properties owned or managed by major single-family real estate companies, reporters used property data in Wake and Mecklenburg counties and state corporation records to create a database of their most common subsidiaries, linked by naming convention, mailing address and company officials. The Anti-Corruption Data Collective supplied additional property transaction data through a research agreement with the real estate tech firm Zillow.

The list of investor subsidiaries was then matched using statistical software with property owner names recorded by the North Carolina OneMap, a state project through the N.C. Geographic Information Coordinating Council to collect and publish property parcel information from all 100 counties.

The N&O and The Observer are making both the investor subsidiary list and the database of corporate investor-owned properties available publicly for all uses.