The coronavirus pandemic has affected every section of Indian society – not in the least the children who developed congenital disabilities in the wake of the Bhopal gas tragedy in December 1984.

These children are members of the families who had been exposed to the highly toxic methyl isocyanate gas that leaked into the Bhopal air on the night of December 2. The official toll in the gas leak from the Union Carbide plant is 2,259 (though some estimates put the number as high as 20,000).

But long after that night, the industrial disaster has had an impact on the health of at least three generations of survivors.

The slow poisoning of the neighbourhoods around the plant had begun before the leak. Chemical waste released by Union Carbide had been seeping into the groundwater for years. Several children and grandchildren of the families who consumed this water were born with congenital disabilities, including blindness, Down syndrome, muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning difficulties.

Despite the challenges, these children benefitted from regular therapy and special education. And then came Covid-19, with its lockdowns, quarantine periods, and disruption of medical services.

I had first documented the children of this tragedy for a photography project in 2018. Between October and November, I returned to Bhopal to understand how the children were coping with the curtailment of the much-needed therapy. Every one of the families featured in this photo essay has been exposed to the gas leak of 1984. Here are some of their stories.

‘Alfez’s Behaviour Has Changed’

Alfez has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Whenever Alfez is angry, he lashes out at his siblings and cousins, but they know why he is behaving in this manner and let him be. Among his favourite playmates is his older cousin Falak.

The lockdown interrupted Alfez’s regular sessions of speech and occupational therapy and special education. “Alfez’s behaviour has changed,” his mother Tarannum said. “With regular therapy, he had started to speak a bit. Nowadays, he urinates in his pants and soils himself. When I ask him why, he gets angry and shouts at me to go away.”

Alfez’s father was one-and-a-half years old at the time of the gas leak. Like many other children in Bhopal, Alfez has been receiving therapy from the Chingari Rehabilitation Centre. Run by the Chingari Trust, the centre works with children from economically weak backgrounds. However, the initial months of the Covid-19 lockdown meant that the children could not visit the centre. After unsuccessfully trying to provide therapy online, Chingari’s therapists began visiting the children’s homes whenever they could, which was usually once a week.

Resuming daily home visits are proving to be a challenge for the therapists. A session at the centre that normally lasted 45 minutes has now been reduced to around 30 minutes. The therapists also find it difficult to cart around the specialised equipment they need to treat the children. This tragic situation has sent Alfez and many other similarly affected children in Bhopal into regression.

Alfez likes to eat rice with dal, but these days, he nibbles at his food. He used to eat chocolates, bananas and apples, but not any more.

The family lives in a single-room house. Alfez’s father Sajid has barely had any income since the lockdown. “I take care of him mostly,” Tarannum said. “I understand his language and his needs. May such children be cured by the grace of Allah.”

‘Yashi Needs Continuous Love and Regular Therapy’

“My daughter needs lots of love, just love,” said Jyoti as she hugged and kissed her 12-year-old daughter Ayushi, also known as Yashi. Ayushi too responded to her mother’s affection. In such moments of happiness, Ayushi, who has cerebral palsy and intellectual disability, gets so excited that her hands shake involuntarily.

Before Covid-19 restrictions, regular therapy helped Ayushi maintain a better sitting posture. She had started to use hand signals to communicate her needs to her parents. When she was hungry, she would keep a finger on her lips. When she wanted to use the bathroom, she would hold her tummy.

The pre-teen often bites her hands when she gets overexcited or angry. Ayushi’s self-biting has increased since the lockdown, Jyoti told me. “Yashi needs only two things – continuous love and regular therapy,” Jyoti said. “It helps her to thrive better.”

Jyoti was five years old when she was exposed to the gas leak. Her brother’s child also has medical complications like Ayushi.

Jyoti and her husband Sushil have devoted their lives to Ayushi and her elder brother. They avoid stepping out of the house for long periods. They don’t travel outside Bhopal anymore, since their daughter is growing up and needs enhanced care.

Therapy helped Ayushi thrive, Sushil said: “Earlier, Ayushi used to have frequent bouts of urinary tract infection and rashes. Now it’s better.”

Ayushi is uncomfortable in crowded places, but she does like to go out every now and then. Her father takes her for a spin on his motorcycle. Ayushi is also interested in music, and listens to songs on a cell phone. She dances by moving her hands.

“We love our daughter as she is,” Jyoti said. “We love to take care of her.”

‘Umair Loves Ice Cream’

Umair loves ice cream. He also likes to drown his biscuits in tea. Nobody may disturb Umair when he is having his cuppa.

Umair is loved deeply by his family. They indulge his ice cream whims. In return, they get a lick on their cheeks.

Umair’s behaviour has changed of late. “Nowadays, he hits me and pinches me hard,” said his grandfather. Umair, who has Down syndrome, has been missing some of his therapy sessions since the lockdown. The 12-year-old boy, who had a tendency to hit or pinch people, has become more aggressive and stubborn. His attention span has also shrunk.

Umair’s father was four years old when he was exposed to the fumes from the Union Carbide factory. The boy began receiving therapy five years ago. “Earlier, he wouldn’t have anything except milk,” said his mother Kausar. “He would lie down all day looking dull. Ever since he began receiving regular therapy, he had begun eating by himself and playing a lot.”

‘Isha Likes Music Videos’

Isha has spastic cerebral palsy, but that doesn’t prevent her from indulging in one of her favourite pastimes – to listen to music and watch videos on the mobile phone.

Eighteen-year-old Isha has found a way around her lack of mobility – she operates her phone with her toe.

“I like to browse videos and share among my friends and relatives,” Isha said. She played me her favourite song – Ishara Karti Teri Nigahen by Sumit Goswami.

A selfie is a little more complicated, since the always-smiling and even-tempered teenager cannot hold anything with her hands.

Isha’s mother Jainab was exposed to the gas leak in 1984. Therapists from the Chingari Centre have managed to visit Isha once a week. She needs the therapy – her muscles are going into hyperextension more than before. She is walking on her toes once again, instead of on her heels when she was being treated more regularly.

“Regular therapy helps my daughter thrive better,” Jainab said.

‘Amaan Likes New Clothes and Good Food’

Amaan is devoted to his father Javed, who drives a truck. The 12-year-old boy, who has cerebral palsy, accompanies Javed on trips around the city.

Amaan also likes new clothes and good food. “If he has new clothes, he will wear them out,” his mother Fatima told me. Amaan also likes to have his photo taken, and enjoys playing with the neighbour’s children.

Both Amaan and Javed were exposed to the gas leak as children.

Since Amaan has excessive involuntary movements, he has to be fed by his mother. He walks on his knees, which can be painful at times. When his knees bleed in the winter, his mother applies ointment on them.

Amaan had been improving with regular therapy, but the lockdown has worsened his condition. He is not able to squat as he used to. He had started to speak a bit, but he has regressed to using hand signals.

He gets angry if his wishes are not fulfilled. “He broken his piggy bank because he wanted recharge his mobile phone,” Fatima said. “I told him I would recharge it, but he insisted on paying for it himself.”

‘Zoya and Her Grandmother’

Zoya holds her grandmother tight when she sleeps. Whenever she is afraid, it is her grandmother Asha Bi to whom she turns.

Asha Bi is all 15-year-old Zoya has. Zoya’s father died a few years ago. Zoya’s mother is in poor health and lives with her own parents. Zoya’s younger brother is being raised by one of her uncles.

Zoya’s father and grandparents were affected by the gas leak in 1984. Asha Bi’s husband died a few years ago. “Zoya used to be so happy with her grandfather,” Asha Bi said.

Zoya has intellectual disability with a wrist drop. One of her uncles too has neurodevelopmental disorders, Asha Bi said.

The weekly home visits by Chingari’s therapists are not enough for Zoya. She has stopped eating her morning meal – roti soaked in dal. She has lost her ability to squat and has become less active. She now has her first meal of the day at one pm – Asha Bi makes sure of that.

“It is difficult for me to go anywhere,” Asha Bi said, caressing Zoya’s hair. “Even if I go out for a minute, Zoya gets frightened.”

‘We Want Manisha to Be Well’

Manju is laughing one moment and crying the next when talking about her daughter. That’s how it often is with parents of children with congenital disabilities.

Manisha’s parents had been drinking the poisoned groundwater pumped out of the Union Carbide plant. Thirteen-year-old Manisha has cerebral palsy and intellectual disability. Her parents have spent close to Rs 3 lakh from their life savings on her treatment. Manisha’s father is a wage labourer, with an average monthly income of Rs 8,000 that barely covers the household’s running costs. The rent alone is Rs 3,000.

“Money doesn’t mean anything for us, but we want our daughter to be well,” Manju said.

Before the lockdown, Manisha was able to eat food and wear clothes by herself. Now that her rigorous therapy has been curtailed, she is completely dependent on her parents and siblings.

During the lockdown, she was literally locked inside a room as the landlady didn’t allow her parents to take her out for a walk. Manisha would shriek in anger, further annoying the landlady and her family.

Manisha is loved by everyone in her family, including her two siblings. She laughs a lot, and is especially close to her father.

‘Nida Loves Chennai Express’

Nida has a scratch on her knees. She loves to show it off. “Now she will show it to everybody,” her aunt said with a laugh, and Nida grinned too.

Nida’s mother was seven at the time of the gas leak. Nida’s maternal grandmother and paternal grandparents were also exposed to the toxic fumes.

Nida is close to her aunt. She plays with her and fights with her. The 12-year-old girl has Down syndrome with alopecia. She misses her hair. When her aunt and seven-year-old sister Shehrish comb their hair, she grabs their tresses and put it on her own head. Your hair will grow some day, her mother Shabana Bi consoles her.

Nida spends most of the time with her cousin Zaid, who is on the plump side. “She plays with my tummy and watches web series with me,” Zaid said. Nida’s favourite movie is Rohit Shetty’s Chennai Express.

Nida loves to dress up. She prefers shorts and T-shirts and sporty clothing, but gets irritated in salwar kurtas. She picks her own clothes and carefully folds the other clothes and puts them back in the cupboard.

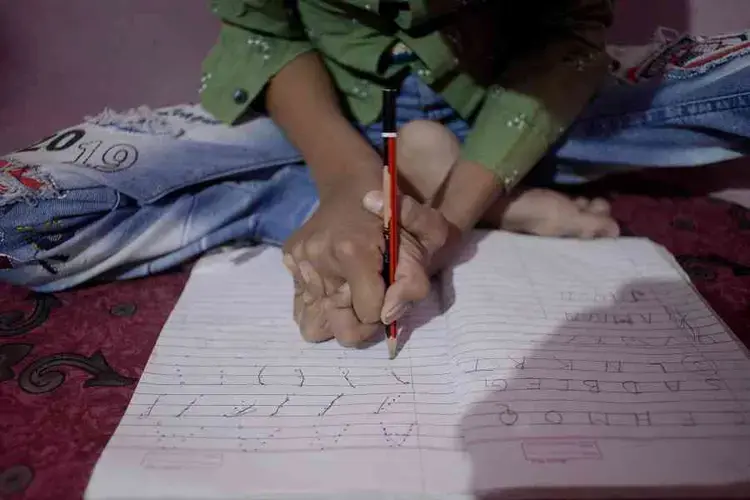

Since the lockdown, Nida has been struggling with her speech and her writing. She has also became lazy, Shabana Bi said. Nida’s father died four months ago, from heart failure. Nida still doesn’t know that her father, who adored her, isn’t around anymore. Sometimes, she looks at the window and says, “Father is there.”

‘Azaan Complains About Us to His Aunt’

Azaan was asleep in his mother’s lap when he had a seizure. This is not new for the three-year-old boy, who has cerebral palsy.

The frequency of Azaan’s seizures has increased in the last six months, possibly because he has been missing his regular therapy sessions. “Regular therapy is very helpful for him,” said Azaan’s mother Nagma. Therapists from Chingari did weekly home visits and hosted video calling sessions with families during the lockdown.

Azaan’s father Abdul often gets emotional when he sees children of Azaan’s age starting to walk and talk. Azaan’s grandmother offers words of comfort— Azaan will be okay; see how much he has grown.

Azaan loves his paternal aunt, and waits for her visits. He rests his little head on her chest and murmurs something into her ear. “He’s complaining about us to his bua,” his grandmother said.

‘What Happens to Naveeda After We’re Gone?’

Naveeda has been called paagal, 'mad,' by her relatives. They won’t even touch the plate in which she has had food. That’s why Naveeda’s mother Arshi has stopped visiting her extended family.

The eight-year-old girl, who has autism, sometimes doesn’t even recognise her parents and siblings. “She looks lost,” Arshi said.

However, Naveeda likes to lie down near her siblings when they study or watch TV. Every night, she sleeps holding her elder sister Gulbasha.

The child likes to wander outside the house, so Arshi keeps the gate locked. She is her father’s pet. He takes her out for a spin on his bike and gets cross with his wife if Naveeda isn’t fed on time.

Arshi and her family were exposed to the gas leak. Her family had been using the contaminated water around the plant for years.

Regular therapy sessions increased Naveeda’s skills. She would ask for food by going into the kitchen and shaking her legs. When she wanted to relieve herself, she would sit outside the toilet and wait for her mother.

The interruption of timely therapy has made Naveeda hyperactive. She wobbles, looks lost and has become less active. She has also been having frequent seizures recently. She has stopped using the only two words she knows, Ammi (mother) and Abbu (father).

“What is the future of my daughter?” Arshi said. “Until we are alive, we can take care of her but what after that?”

‘We Prioritise Zunaid’s Diet’

Zunaid hates to be dependent. The 14-year-old boy, who has Duchenne muscular dystrophy, doesn’t like to ask for help to eat or use the bathroom.

Zunaid’s elder brother Tauhid had the same muscle disorder. He died at the age of 14 in 2016 (life expectancy with DMD is low).

Zunaid’s parents lived in the vicinity of the Union Carbide plant as children. They breathed in the malevolent air in December 1984. Zunaid’s mother Nargis remembers a “burning sensation” in her eyes that night.

Zunaid and Tauhid used to practise art and craft until their muscles began to weaken. Tauhid’s death deeply affected Nargis. Her own mother died from throat cancer in 2003. Her husband was recently operated on for cancer.

The family lives in a 100-square-foot single room. Zunaid’s father, who is a fruit vendor, has found it difficult to work since his surgery. The lockdown has affected Nargis’s roti-making business too – orders have been drastically reduced.

Yet, the family is determined to ensure that Zunaid gets his daily intake of protein. “We always priorities Zunaid’s diet irrespective of our financial situation,” Nargis said.

‘Tahmina does drama’

Tahmina loves to dance to her favourite music. She longs to go out. She often stands by her window and peeps outside. Regular therapy had helped 15-year-old Tahmina cope with her autism and ADHD and reduced her fear of heights and loud sounds.

Tahmina’s father, his mother and his sisters were all exposed to the gas leak. Tahmina’s grandmother still complains of breathing problems.

“We used to live near a cinema hall,” Bhoori Bi recalled. “Around midnight, we heard noises from the cinema hall. People were running indiscriminately, they were coughing. I too began coughing. My eyes had a burning sensation, and I fainted after a while. I couldn’t see for around two weeks after the tragedy.”

Tahmina is most attached to her mother, Tasleem. “If her mother goes outside even for a short while, she will keep asking for her ammi,” Bhoori Bi said.

Tahmina “does drama,” Tasleem added with a laugh.

Tahimna likes to eat samosas. A couple of years ago, she accidentally drank floor cleaner, thinking it was the Rasna cold drink. “She almost died,” Tasleem said. “This is her second life.”

Therapy vastly helped Tahmina. “She needs occupational therapy along with speech, special education and physio,” her therapist Huma from the Chingari Rehabilitation Centre said. Tahmina is now walking on her toes again. She has become less active, and her communication has been affected.

“She doesn’t get along with strangers,” Tasleem said. “When someone visits us at home, she goes inside.”

Rohit Jain is an independent photographer based in Delhi. This photo project was made possible by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.