LA OROYA, Peru – In Pope Francis' teaching doctrine on climate change and environmental sustainability, released in June to worldwide attention, he intertwines two threads that often dangle separately: nature and the world's poor.

"A true ecological approach always becomes a social approach," Francis writes in his papal encyclical. "It must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor."

There are few places on Earth where the cry of both is louder than in this city of 33,000 more than 2 miles high in the central Andes. La Oroya, Peru, is recognized as one of the world's most polluted places. A smoke-belching smelting plant for copper, zinc and lead, operating from 1922 to 2009, made it so. Chernobyl makes those same lists.

Every child in town has excessive levels of lead in his or her blood, according to health officials. The soil is contaminated with sulfur dioxide. Portions of the Montaro River, which flows past the smelting plant, has been dead for years. Seven decades of acid rain chemically transformed the mountains surrounding the plant so that they look like molten wax, not solid rock.

The Earth is surely crying in La Oroya. And so are the poor. Just not in ways Pope Francis envisioned.

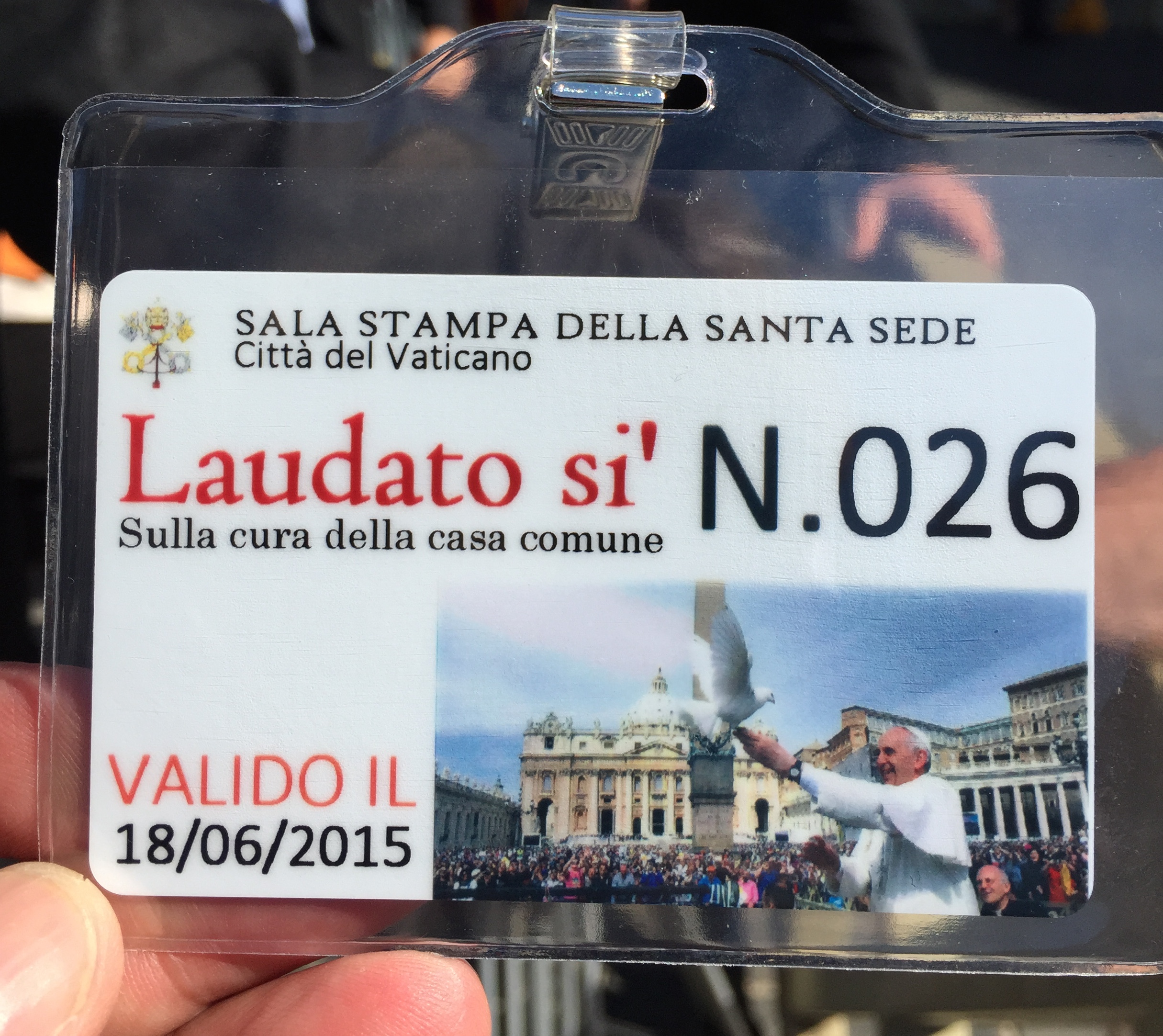

That revelation from South America comes as the pope, the global leader of 1.2 billion Catholics, prepares to visit the United States for the first time. He will speak to both a joint session of Congress and the United Nations. His encyclical – a relatively rare teaching tool of high moral authority – is called Laudato Si, On Care for our Common Home.

He will likely urge Congress and U.N. delegates to take seriously his conclusions that the Earth is in peril because of rampant consumerism, unmitigated plundering and processing of natural resources, and far too much burning of fossil fuels. And he wants global leaders to act, mostly on behalf of the world's exploited poor.

But in La Oroya, it appears the poor want to be exploited. They are screaming, protesting, even dying for the 77-year-old plant to be sold to a new owner and reopened – at environmental standards far lower than Peruvian law now allows. The plant, called Doe Run after the last U.S-based owner, closed in 2009 after environmental standards were increased.

It's not just the 1,600 direct jobs at stake; La Oroya's entire economy – shops, restaurants, suppliers, hotels – hinges on the smelting plant. Like Winston-Salem in the 1980s, where signs proclaimed "Pride in Tobacco," residents here are proud of their plant despite the ravaging impact on their health and their community. The plant is prominently displayed on the city seal.

Emel Salazar Yuriulca, 43, president of the Federation of Unemployed in La Oroya, agrees with the social elements to which Pope Francis speaks regarding the environment. She is a devout Catholic. She reveres the first Latin American pope.

But, she says, speaking at a park just across the river from the shuttered plant: "The life of that plant is more important than anything the pope says. Yes, we are poor. But that's because the plant closed. That's when the problems of poverty started."

Freddy Rojas Chacha, 40, the elected president of the Community of Old La Oroya near the plant, adds: "We must respect the view of the pope. But if he says the plant should not reopen because of pollution, what solution does he offer? Where will we work? We must support our families."

Teofilo Rojas Zavallos, 54, another devout Catholic who worked at Doe Run for 28 years, says simply, "We are well aware of the pollution. But the pope is not going to hire me."

Pope Francis is astute enough to recognize the conundrum in which the poor of La Oroya find themselves. He is not asking them to choose health over work. He believes they are entitled to both, and that business and government leaders are responsible for the fix.

"We are faced with not two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both," he writes. "Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature."

Still, given the vast and vexing scope of the problem worldwide, it's possible Francis has overestimated his ability to affect global climate-change policy and thinking – even among the world's poor, to whom he has dedicated his papacy. He is eager to influence the U.N. climate summit negotiations in Paris in December, but even that might be beyond his reach.

The importance of Peru

This realization of Pope Francis' potentially limited moral authority became clear after three weeks of reporting in his home continent, in a country that is 75 percent Catholic, that is crucial to battling global warming because of its vast carbon-capturing tropical forests, and where his approval rating tops 80 percent.

The pope is beloved from the Pacific Coast capital of Lima, home to nearly 30 percent of Peru's 30.3 million people, to the mining region of the central Andes, to the farm region in the desert south.

And while there is great support for the encyclical among environmentalists, progressives and many church leaders, Peru's business elite, for example, easily separate their admiration for Pope Francis from their disdain for his views on capitalism, free market economies and his call to transform both in order to sustain life on Earth.

"When I read the encyclical, it just makes me angry," says Elena Conterno, president of the National Society of Fisheries (Peru is the world's No. 1 fishery). "I see a pessimistic view toward entrepreneurs, investors and economic leaders. He undertook this complicated issue, and I believe he doesn't have the knowledge to know how to tackle it. If I were his adviser, I'd say, 'Get out of it.' "

Pope Francis, possibly anticipating reaction, writes, referring to business leaders like Conterno: "Their behavior shows that for them, maximizing profits is enough. Yet by itself the market cannot guarantee integral human development and social inclusion."

The pope adds that economists and financiers believe in the "lie that there is an infinite supply of the Earth's goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry beyond every limit."

Roque Benavides, CEO of BuenaVentura, Peru's largest precious metals mining company, scoffs at the very notion. A non-practicing Catholic interviewed in Lima in his 21st-floor conference room, he has read the encyclical and found it wanting.

He never worries that his scores of mines in Peru extracting billions annually in gold, silver, copper and zinc will run dry any time soon. The company's first mine, dug 62 years ago, is still producing gold, he says proudly.

"The fact is, we all have to worry about environmental issues; regulations here have gotten stiffer," Benavides says. "But in a country like Peru, you can't stop economic development because of environmental issues."

There is a ring of truth to that. Largely because of the recently soaring value of precious metals – prices remain high, though now in decline – Peru has ranked among the world's fastest-growing economies in recent years. Annual growth peaked at 6.2 percent in 2012 and remains over 5 percent. While mining makes up 15 percent of Peru's GDP, it accounts for 60 percent of exports and fills government coffers with taxes.

And while there is disagreement over cause-and-effect, the steady growth of Peru's mining industry since 2001 has come concurrently with a huge drop in the poverty rate – from 50 percent 15 years ago to 26 percent today.

"We are a mining country and have been one for centuries," says Pedro Solano, executive director of the Peruvian Society for Environmental Law, a group in full support of the papal encyclical. "It is hard for any government here to not be economy-driven by the mining industry."

Long-term potential

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal is Peru's minister of the environment, President Ollante Humala's longest-serving Cabinet member. He was the relentless host of the U.N. climate summit in Lima last December. Long after deadlines had passed, he allowed delegates to neither leave, nor even sleep, until a broad agreement to voluntarily-set carbon emissions limits was drafted.

Another nonpracticing Catholic, Pulgar-Vidal has not only read the encyclical, he has studied it. He ordered his staff to read it. He believes its long-term potential is vast, and that its eventual impact, driven by an equally relentless pope, will play into negotiations in Paris, where the minister will enjoy a leading role.

"It's very difficult for some people to accept because it was written by the leader of a religion," Pulgar-Vidal says. "But I can tell you, it doesn't read like a religious text. It is written with the language of a poet, with the precision of an engineer, and by a leader with the moral authority to have influence."

By late July, word of the encyclical was just reaching Cocachacra, a small farming town near the Pacific Ocean and just above the border with Chile in southern Peru. The response to it here stands in stark contrast to the reaction in poisoned and polluted La Oroya.

In 2009, the government approved the first-ever mine in the southern region, a copper mine next to the Tambo River. Plans call for a 1,300-foot-deep open-pit mine called Tia Maria, excavated for 18 years.

Southern Copper Co. of Mexico, one of the world's largest copper mining companies, has pledged to follow the highest environmental standards. But it has a public record of environmental abuses to water, air and workers dating back 30 years in Peru and Mexico.

The valley, which supports 15,000 farming families who grow sugar cane, potatoes, onions, rice and garlic, is something of a miracle. The desert valley gets virtually no annual rainfall; life there depends on the groundwater and glacier melt that forms the Tambo River. Farmers believe firmly that Tia Maria will destroy groundwater and kill the river; they also believe that toxic dust from mining – just 500 yards from the farm valley – will kill their crops before the water sources die.

Some 3,000 farmers, led by farmer-activist Jesus Cornejo, have so far battled Southern Copper to a stalemate. But not without cost. Four anti-mine protesters were shot dead in 2011 by the Peruvian military; three more died last April. Cornejo has been jailed and held without cause. Martial law was imposed for months.

After reviewing a Vatican-produced summary of the papal encyclical, the farm activist brightens: "It is important because we are confronting very big powers. We all believe the church should have a more active role here. And not all of them are on our side, or the side of the environment. This is now out of step with what Pope Francis is calling for."

Cornejo vows to distribute copies of the encyclical to fellow protesters. The timing is good, he says. Southern Copper CEO Oscar Gonzales told Reuters in late June that he intends to settle all disputes with the opposition and start construction of Tia Maria in December.

Cornejo just shakes his head. Neither the company nor the government has yet listened to their concerns. This is not La Oroya. The poor Peruvians here in the south are used to clean air and clean water. The pope and his encyclical appear to be hardening the protesters' resolve.

Pope Francis writes: "The export of raw materials to satisfy markets in the industrialized north has caused harm locally, as for example … sulfur dioxide pollution in copper mining."

"As long as the people oppose (Tia Maria) in the numbers we have on our side, the mine will not go forward," Cornejo says. "Until the government starts to listen, we will fight. We hope the encyclical will raise awareness of our need to be heard."

--

A version of this story also appeared in the Miami Herald, the Kansas City Star, and the Sacramento Bee.