Omar Rani is an Orang Asli who lives in the village of Kampung Berengoi in the Malaysian state of Pahang. Omar and his fellow villagers, also members of the indigenous group, are illiterate – or as they put it: “We haven’t gone to school”.

Last year, they were asked to sign letters to receive free houses from private company YP Olio Sdn Bhd. Though unable to read a word, Omar and the villagers signed – they trusted the government officers who accompanied the company’s representatives.

If the villagers were able to read the letter, they would have seen it stated that they “have no objection to development project on YP Olio’s land”, the nature of which was left unspecified.

But earlier this month, the Orang Asli villagers received shocking news. YP Olio might have misconstrued their acceptance of houses as support for its logging and plantation project, something they have been protesting since 2019.

“I didn’t know that taking the houses meant accepting the logging,” says 37-year-old Omar. “Nobody said the letters were about logging.”

A lawyer supporting Malaysia’s indigenous groups has labelled the contract process as “fraudulent”, while another said it was guilty of “exploiting the Orang Asli”.

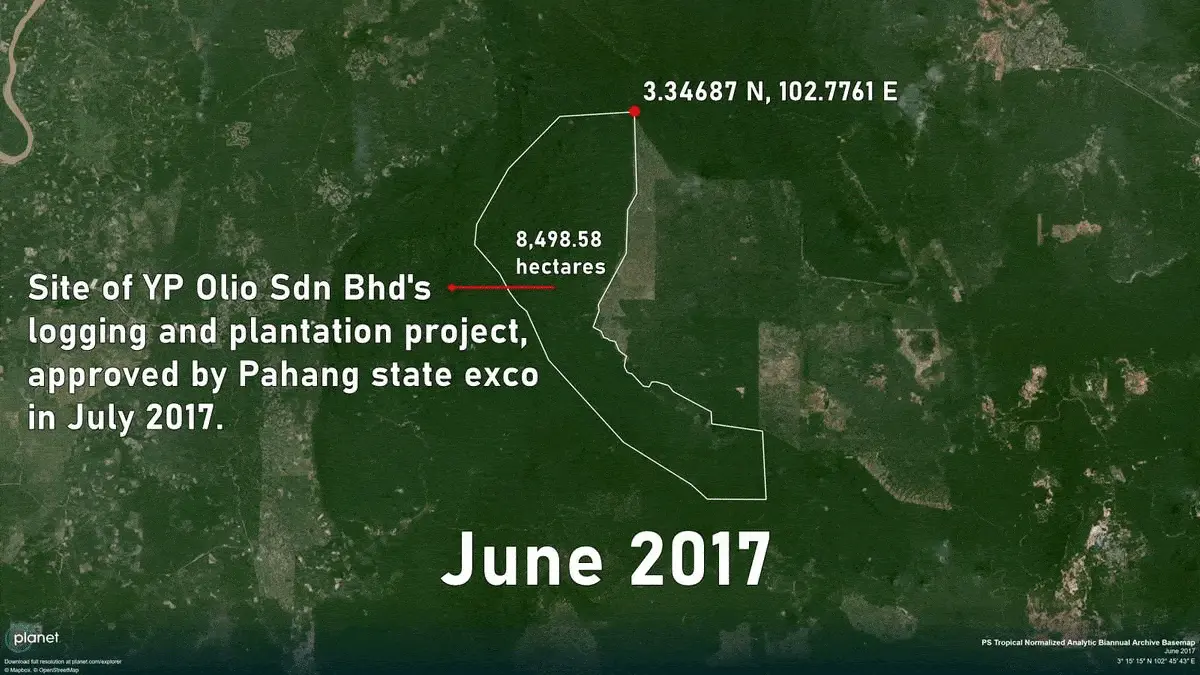

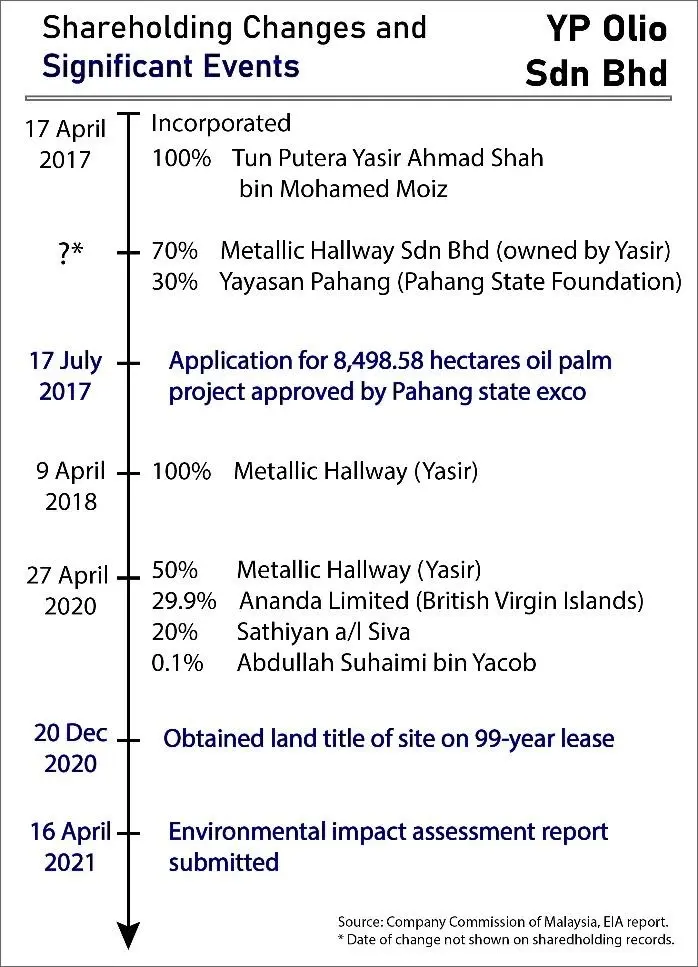

The YP Olio Sdn Bhd project will clear 8,498.58 hectares (about 85 km2) – Pahang’s largest single forest loss for two decades – in what had been a forest reserve until late 2020. The company is set to turn the site into plantations of oil palm and Paulownia, an exotic tree grown for timber, with the project’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) report currently being reviewed by the federal Department of Environment.

But concerned groups are criticising the project for destroying habitats of endangered wildlife and displacing indigenous people, with at least eight Orang Asli families, including Omar’s, living in two villages on the site.

The events unfolding at Kampung Berengoi are just the latest in indigenous communities’ long standing struggle for customary land rights across Malaysia, one that appeared to take a turn for the better in 2018 when the Pakatan Harapan coalition was elected into federal government on a reformist agenda that included defending indigenous rights.

But the Pakatan Harapan government collapsed in February last year, and since then, Orang Asli land rights disputes have shown no signs of easing, with the Kampung Berengoi community exemplifying the continued struggle of Malaysia’s indigenous groups.

“Land-grabbing has been an on-going tough situation faced by the Orang Asli for decades,” Jerald Joseph, a commissioner of the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM), told the Globe. “It’s getting worse as a clash between development and the traditional lifestyle of the Orang Asli.”

“Ironically, Orang Asli are not against development, but they want development that is sustainable and [doesn’t] destroy their land and ancestral cultures.”

About 220,000 Orang Asli, a term meaning ‘first’ or ‘native’ people in Malay that encapsulates numerous indigenous groups, live in Peninsular Malaysia. The poorest, most malnourished, and least educated people in the country, land insecurity exemplifies their daily plight.

For decades, Orang Asli have had to wage courtroom battles and erect blockades to assert their rights. An uplifting change came in April 2019 when the newly elected Pakatan Harapan federal government held the first National Orang Asli Convention. Indigenous people delegates outlined their struggles and attendees concluded 136 resolutions, with recognition of land rights topping the list.

In response, the then-federal government began drawing plans to implement the resolutions. But that government was ousted following Malaysia’s political upheaval in February 2020 that saw Mahathir Mohamad’s coalition collapse in a flurry of infighting.

As the government has undergone an overhaul in the time since, that nascent trend of indigenous rights reform has quickly ended as land disputes with the Orang Asli have continued to pile up. Over the past six months alone, at least three Orang Asli communities have received eviction orders after state governments leased the land to developers.

We love the forest, we cherish the rivers. We cannot accept an intrusion of our land

Just two years ago, Omar could step out of his hut into the adjacent forest and walk westward for more than 15km under the canopy. He would have seen signs of tapirs, sun bears, leopard cats, and elephants. Perhaps even tigers.

But loggers started clearing the forest in late 2019. Within a year, bare soil stretched for 5km west of Omar’s hut, with the logging continuing unabated today.

“We love the forest, we cherish the rivers,” Omar tells the Globe. “We cannot accept an intrusion of our land.”

Rani Jinal, Omar’s father, collects fruits, rattan, gum, and medicinal plants from the forest.

“My livelihood cannot continue [without the forest],” he said. “My food in the forest will be gone. How can I support [the logging project]?”

YP Olio has possession of the project site on a 99-year lease from the Pahang state government, with the lease starting on December 20, 2019.

The site encompasses 4,047 hectares of customary territory claimed in 2017 by Orang Asli villagers, something the state government hasn’t recognised to date.

“In Pahang, they have a very bad track record in recognising and protecting Orang Asli land rights,” Dr Colin Nicholas, who holds his PhD in Orang Asli issues and founded the Center for Orang Asli Concerns in 1989, told the Globe.

Nicholas cites government data that shows only 7,156 hectares of Orang Asli customary land as being gazetted – formally recognised through legal government notices – as aboriginal areas or reserves in Pahang. About 45,000 hectares more have been pending for years.

“It’s a very clear case that the government is not protecting,” said Nicholas. “And because these lands are not secured in the Orang Asli’s name, anybody can take it.”

Between September 2019 and December 2020, loggers cleared at least 1,684 hectares of forest on YP OIio’s land around Omar’s village, according to figures in the EIA report. The resident Orang Asli denounced the logging, and in November 2019, Omar submitted a letter, with the help of a literate relative, to multiple government agencies protesting YP Olio’s project in their customary territory.

He was not a lone voice. The EIA report shows that 85% of Orang Asli villagers surveyed in and near the site objected to the project. In Omar’s village of Kampung Berengoi, all respondents objected.

“[If the project continues] our farms and all the trees will be cut. They have already damaged our ancestral graves,” Omar said. “We don’t have a place to move to. How to move? This has been our place inherited through generations.”

Four of the signees – Omar, Rani, Sani Kotiz, and Maarof bin Abdullah – told the Globe they signed the letters without knowing they were related to logging.

Kai Ping Hon, a lawyer and member of the Malaysian Bar Council’s Committee on Orang Asli Rights, labelled the consent letters as “fraudulent”. If the Orang Asli did not know that accepting the houses implies consent for the logging and plantation, they “must write to revoke their signatures”, Hon told the Globe.

“On top of that, they should actually sue the various authorities, especially if the project gets the go-ahead.”

SUHAKAM’s Joseph says the consent letters “definitely don’t meet the standard for meaningful prior, free and informed consent”.

Joseph says that such discussions with the Orang Asli must be done in the presence of representatives “who have [the Orang Asli’s] interest at heart”, such as civil society organisations or lawyers from the Malaysian Bar Council, to “avoid gaps or misinterpretation”.

In this case, the consent letters are “exploiting the Orang Asli’s understanding by not giving full disclosure of the project to the affected and original peoples of the village,” he said.

The Department of Environment told the Globe that they are investigating allegations of deception in getting the Orang Asli to sign the consent letters. The Chief Minister of Pahang did not reply to the Globe’s request for comment.

The directors of YP Olio, through their appointed lawyer, refute allegations of fraud and misrepresentation in dealing with the Orang Asli.

YP Olio has four directors. The founding director is Tun Putera Yasir Ahmad Shah bin Mohamed Moiz, who also owns 50% of the company through Metallic Hallway Sdn Bhd. Yasir is nephew to the Sultan of Pahang, who is also Malaysia’s current ruler as king.

In a statement to the Globe, the directors say YP Olio “adheres to proper protocols and management” and that it “works closely” with the relevant government agencies and is “in strict adherence with the law”.

The Globe asked the directors if they believed that the villagers had consented to the company’s logging and plantation project, a question which they did not answer. The directors say that the company has always engaged the Orang Asli in the presence of the Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA), the government agency mandated under the Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954 to oversee Orang Asli affairs.

Omar and Rani confirmed that JAKOA officers had accompanied YP Olio’s representatives during visits and signing of the letters. But the officers did not say the letters were linked to logging, say Omar and Rani.

Nicholas, the coordinator of the Center for Orang Asli Concerns, contends that JAKOA has “failed their responsibility to inform the Orang Asli of what is in store for them in signing this agreement”.

“According to the law, JAKOA are supposed to protect the interests of the Orang Asli, for their well-being and progress,” said Nicholas. “JAKOA have failed in their fiduciary duty for the Orang Asli in this case.”

The Globe’s enquiries to JAKOA, the Forestry Department of Pahang, and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia were not answered.

On its part, YP Olio has promised to prioritise the Orang Asli for job opportunities in the new project. The EIA report concludes that the project can develop the economy and mitigate environmental impact, outlining mitigation measures like drainage systems to reduce erosion, electric fences to deter elephants, and new protected areas for wildlife.

But surveys in the EIA report show that almost all local Orang Asli respondents disagreed that YP Olio’s project would give them jobs or improve their income. Rather, they rejected the project due to concerns of water pollution, loss of forest products, and damage caused by logging roads.

But while developers would benefit from selling logs and palm oil, the potential losers from the project’s environmental fallout span indigenous groups, local residents, as well as the state and federal governments.

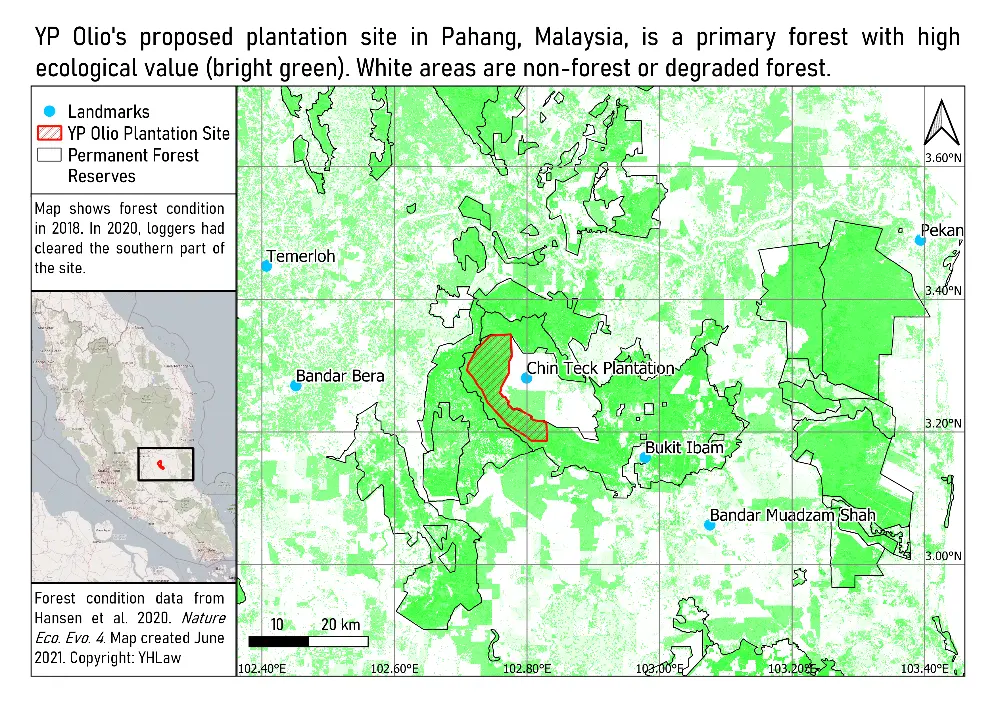

Besides displacing Orang Asli, the project will destroy thousands of hectares of forests and prime wildlife habitats. Google Earth images dating back to 1984 show that the site was last logged sustainably in 1989-1994. In Malaysia, forest reserves are selectively logged every 25-30 years for reduced impact, and by 2018 the forest had regenerated into an ecologically rich area with trees taller than 30 metres. But now, the forest is set to be cleared without the prospect of regeneration.

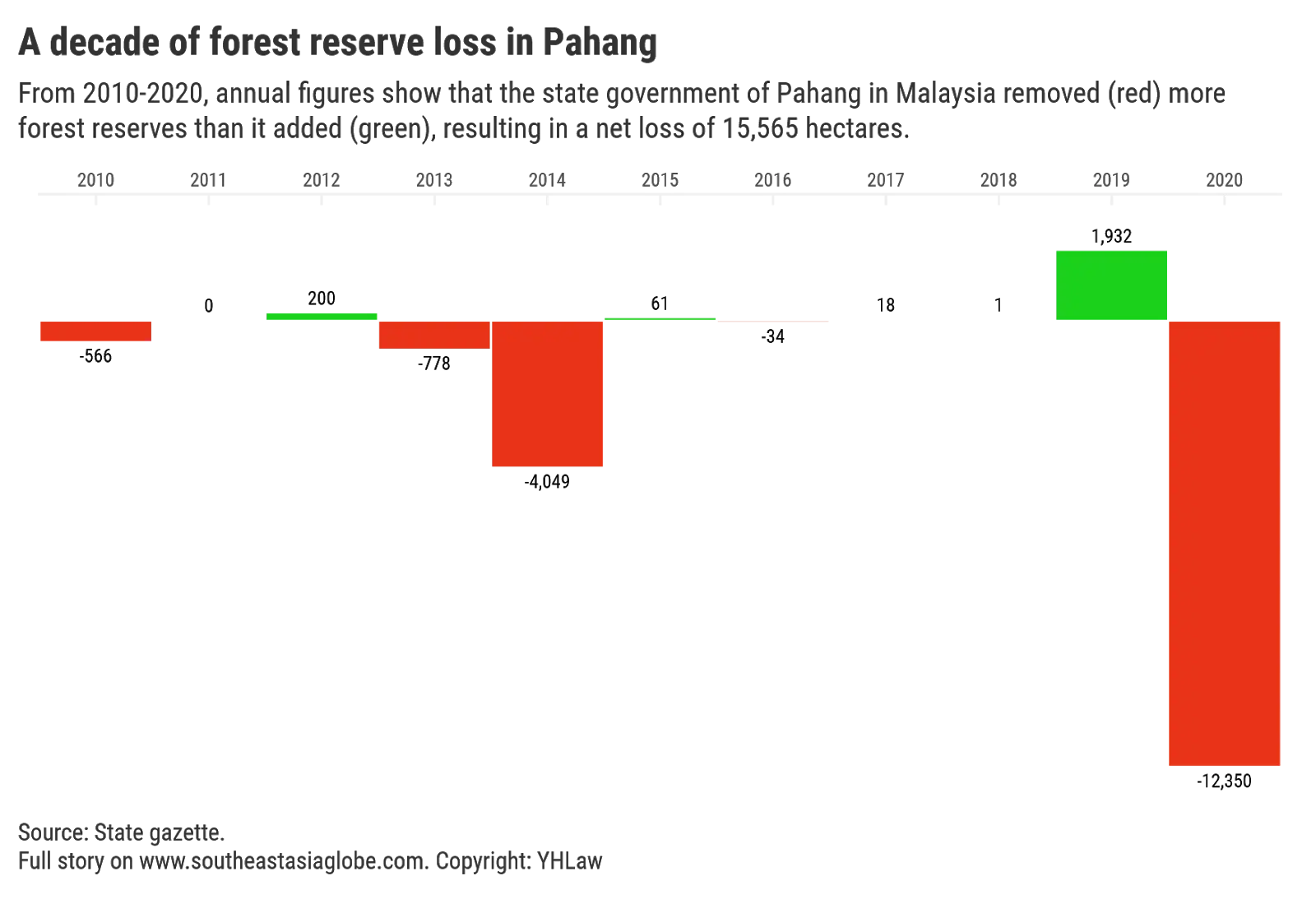

Pahang today is the most forested state in Peninsular Malaysia, but over the last decade, it has lost forest reserves of 15,565 ha. This project site, at nearly 8,500 hectares, is the largest forest reserve loss in Pahang in the last two decades.

Continued loss of forest reserves in Pahang is not sustainable, says Balu Perumal, head of conservation at the Malaysian Nature Society (MNS). Although the state government approved YP Olio’s project with the condition that the forest lost will be replaced, Perumal “doesn’t see this happening at this stage”.

The EIA report also estimates that over the next 30 years, YP Olio’s project would incur a net loss in environmental services of $9.5 million. This loss means that sales of timber and palm oil is insufficient to offset the cost of losing forest functions like carbon sequestration.

“The state government should not have degazetted and given the forest for conversion in the first place,” said Perumal. MNS was invited by the Department of Environment to review the project.

The area sits between coastal peat swamp forest and interior wetland forest.

“Losing this area to plantation and other unsustainable activities” will ruin the integrity of the forest landscape, says Perumal. He warns that cutting off space for large mammals to move and locking them into isolated forest patches would escalate conflict between wildlife and humans.

Recent surveys by environmental consultants found sun bears, gibbons, leopard cats, and the endangered tapirs in the forest. The site is believed to house endangered helmeted hornbills, while Omar says elephants live there too.

There are suggestions that tigers use or live in the project site too, with a recorded incident involving the animal occurring in the area in 2017, according to data cited in the EIA report. Ironically, one of YP Olio’s directors, Felix Danai Link, is associated with tiger conservation in Thailand.

Link is also a director of Thailand-listed energy conglomerate B. Grimm Power PCL, and son to B. Grimm Power’s president, Harald Link – both of which have been supporting WWF Thailand’s tiger conservation for seven years. Neither Felix nor Harald Link responded to the Globe’s inquiry.

We make our livelihood in the forest. Come lightning, storm, elephant or tiger, it doesn’t matter

But fundamentally, “the party that has betrayed the Orang Asli’s trust is the state government”, says Nicholas, the expert on Orang Asli matters.

“Ultimately, we have to go to court … It will involve a lot of work, but legally, in terms of rights under the common law, they have a very good case,” said Nicholas, citing various precedents where the Malaysian courts have recognised the Orang Asli’s customary rights.

“We make our livelihood in the forest. Come lightning, storm, elephant or tiger, it doesn’t matter,” said Rani.

A dozen villagers gather around him and his son Omar raises one fist in the air.

“Now, what do the government and the big officers want? Have they no compassion or thought for us, the people in the forest?” said Rani.

“We do not agree!” the villagers respond. “We protest the logging!”