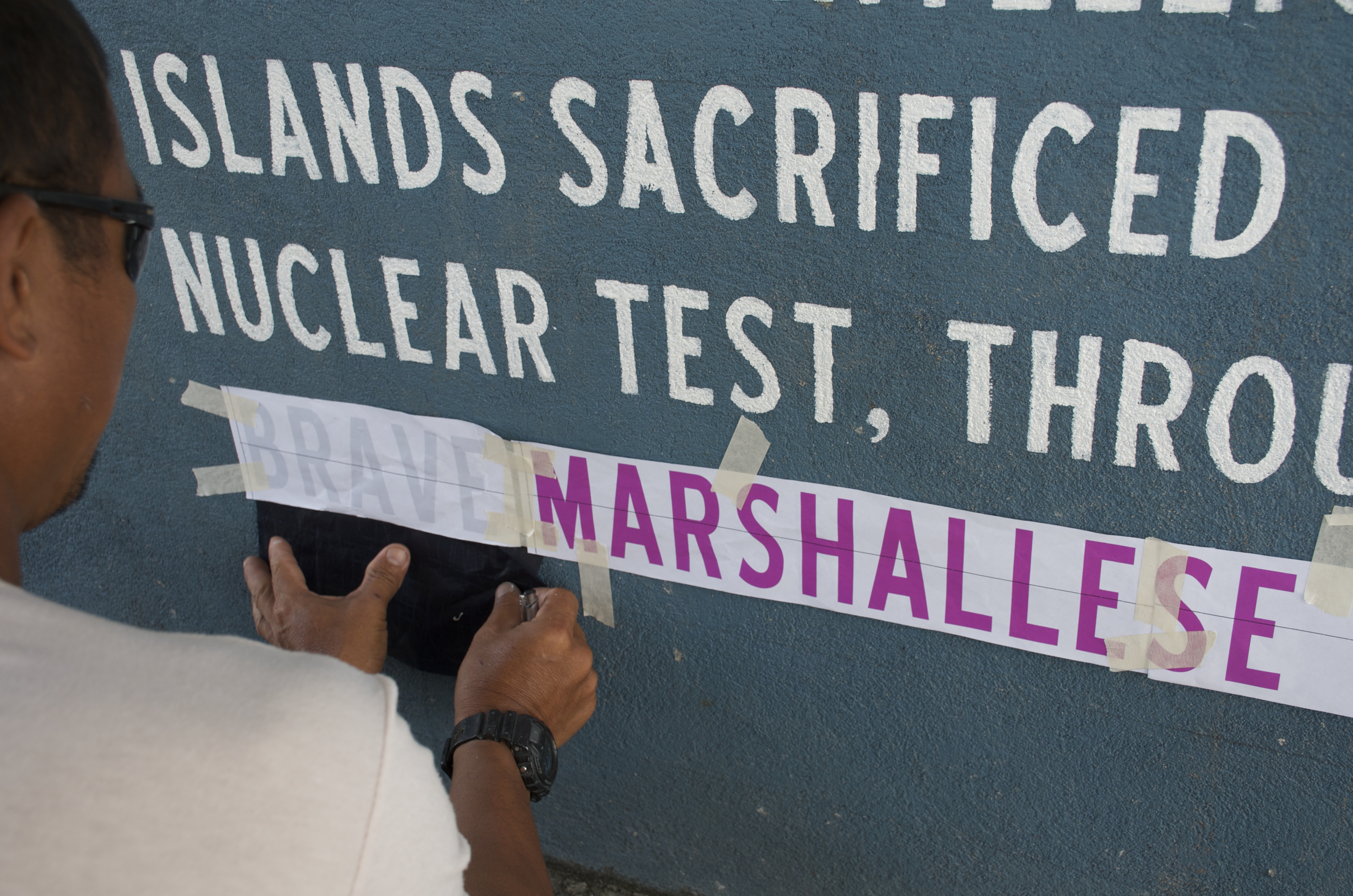

The Marshall Islands isn't afraid to invoke its moral standing, at this week's Paris climate summit and elsewhere. After enduring nuclear-weapons tests in the 20th century and the rise of sea levels today, the people of this low-lying Pacific nation are experts in existentialism. But morals don't pay the bills, and both Americans and the Marshallese still dream of turning this former ground zero into a tourist paradise.

In the mid-20th century, the Marshallese atolls of Bikini and Enewetak were the tests sites for detonations equal to millions of tons of TNT. Rongelap and Utirik atolls, to the east, bore the brunt of radioactive fallout that damaged generations of Marshallese. The combined force of the tests was equivalent to detonating 1.6 Hiroshima-caliber bombs every day for 12 years.

But today much of the Marshall Islands is absurdly beautiful. Majuro Atoll and the northern island of Ebeye are plagued with problems — they now host nearly three quarters of the in-country population of 53,000 — but they are just two pieces of a scattered puzzle in Micronesia.

I went to the islands in February and March. The capital of Majuro is just two flights from Washington, D.C., via Honolulu, across the International Date Line. Many of the 29 atolls are remote, but Majuro offers a study in extreme contrasts.

The private island of Enemanit is 20 minutes from the capital, if you travel by Jerry Kramer's boat for one of his Sunday barbecues, and it's like another world. Kramer, 73, is sometimes referred to as the Donald Trump of the Marshall Islands — in a business sense, that is — though on a Sunday afternoon in March he seems dressed for a Jimmy Buffett concert.

"I get Charles Schwab's son, the GoPro guy," he says, listing guests whom he allows to anchor just offshore. "Larry Page sends a jet just to get something he wants to eat."

Off the port side of Kramer's boat, the Google co-founder's yacht looks like a spaceship. It is thin, sleek and reportedly 240 feet long and worth $45 million. Page may or may not be on board. He may be surfing in Ailinglaplap Atoll, where silky waves break on an aquamarine Eden.

Kramer runs a construction company, the second-largest private employer in the Marshall Islands. He owns 100 apartments, a couple of hotels and the buildings that house the embassies of Japan, Taiwan and the United States. He arrived in the Marshalls from the United States as a missile technician in 1961, back when it was a U.S. territory and all travel in the islands was restricted by the military. He fell in love with a local woman, raised a family and built an industrial empire in Majuro.

Kramer's passengers on this particular Sunday include his grandchildren, a few dozen visitors from Taiwan, a U.S. State Department official and his family, and chihuahuas named Buster and Snooki. He sees endless economic opportunity in the beauty of the Marshalls, but quickly lists the obstacles: a native workforce still wary of radioactive contamination, a regional airline that is often grounded, a government riddled with corruption.

Tourism in Bikini Atoll "could be a billion-dollar industry," says Kramer, sitting on the transom of his boat. "It could finally be something that makes amends." Divers might pay top dollar to inspect the china still sitting in the captain's quarters of the USS Saratoga, an aircraft carrier purposefully sunk by an underwater nuclear test in 1946.

Bikini's last fledgling scuba operation flamed out in 2008 with the global economy. Today there are about a half dozen people who live there: a few from the Bikini Projects Department and a few from the U.S. Department of Energy. There are a couple of houses, a garage, a generator, a reverse-osmosis unit for drinking water, a gazebo on the beach, and warships from World War II at the bottom of the lagoon. Rongelap Atoll has also not been resettled, mostly because the Marshallese don't trust the U.S. government and because younger generations have gotten used to living in more urban, connected environments.

There is one billion-dollar industry in the Marshalls, though: tuna. Majuro Atoll's lagoon serves as a transshipment hub for foreign purse seiners who pay $8,000 a day for fishing rights. Cold-storage motherships ferry the "blue gold" to ports around the Pacific rim. But still the nuclear legacy creeps into modern-day concerns: what if old deposits of contaminated soil were disturbed and released into fishing waters?

The Runit Dome is a large concrete cap on Enewetak Atoll that covers 110,000 cubic yards of radioactive soil buried in a 350-foot-wide test crater. The United States constructed the dome in 1980, after 4,000 American servicemen finished cleanup operations. The capped soil, sown with plutonium, will be dangerous for thousands of years. The dome, which would fail even a landfill inspection if it were in the United States, is already showing signs of structural instability as tides nibble away at the concrete. But any release of the dome's contents would pale in comparison to the volume of contamination that's already in Enewetak's lagoon sediments, according to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

Enewetak has been partially resettled by several hundred Marshallese, though the American servicemen who handled its cleanup are still fighting to get health care and compensation for cancers and ailments linked to contamination. On Nov. 2 a bill was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives to classify those servicemen as "radiation exposed veterans." Similar bills have been introduced over the years, to no avail.

Jerry Kramer's island of Enemanit is a happier setting: a cup of rosé, a leg of grilled chicken, palm-tree views that are almost too idyllic, like a screensaver on a Windows 95 desktop computer. A 45-minute flight away, though, 500 Bikinians are struggling on the rocky island of Kili, where they've eked out a living since nuclear exiles were relocated there. A ship bearing food and diesel arrives every three months, if the weather behaves. In February, the yearly king tide washed completely over the island, fouling freshwater reservoirs. In a place where everything is a coastline, where the nuclear legacy still lurks, bigger tidal and storm surges are a modern insult to a 20th-century injury.

"We can't be living like this," says Lani Kramer, Jerry's daughter-in-law, who in the spring was running to be mayor of Bikini Atoll and its resettlements of Kili and Ejit islands. "We need to create jobs … but it's not just about money. It's about human rights. And it's sad because most of the people who are exposed are gone."

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Dan Zak

"So we (the U.S.) tested 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands from 1946-1958. If you take the...