UNITED NATIONS — An attempt to strengthen and expand the world's premier arms-control treaty ended in failure here Friday as international delegations squabbled over a long-sought goal of establishing a ban on weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East.

Following four weeks of negotiations, the United States and several of its allies rejected the conference's final document, which was supposed to further the implementation of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

The United States and Britain refused to accept the establishment of an "arbitrary" deadline to hold a conference on a zone that would be free of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East, and Canada objected to a process that didn't include Israel, which has not signed the treaty.

Iran's delegate Hamid Baidinejad accused the United States and Britain of blocking consensus in order "to safeguard the interests of a particular non-party of the treaty which has endangered the peace and security of the region by developing nuclear-weapons capability" outside international controls.

The treaty was enacted 45 years ago to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and to reduce and ultimately eliminate existing stockpiles. It now has 191 state parties, and conferences are held every five years to review its status and direction. Discussions this month ranged beyond the Middle East — from the conflict between Russia and Ukraine to North Korea's errant missile tests, from stockpile modernizations underway in every nuclear-armed state to a coalition of non-nuclear states who are trying to lay the groundwork for a global ban on the weapons.

Frustration grew from the moment the conference opened on April 26, when delegates delivered prickly remarks that recalled old grudges. From the dais in the United Nations' majestic General Assembly Hall in midtown Manhattan, Russian delegate Mikhail Ulyanov called U.S. missile-defense programs in Europe "a serious obstacle to further disarmament." Secretary of State John F. Kerry knocked Russia for violating the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty and refusing an offer to reduce its stockpile of nuclear warheads by one third in tandem with the United States. Together the two countries possess 94 percent of the world's roughly 15,700 warheads, according to the Federation of American Scientists. Kerry's counterpart in the Iranian nuclear negotiations, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, blamed nuclear-armed states for a lack of progress since the last review conference in 2010.

"We call upon the nuclear-weapon states to immediately cease their plans to further invest in modernizing and extending the life span of their nuclear weapons and related facilities," Zarif said in his opening remarks.

The United States has embarked on an overhaul of its nuclear arsenal and infrastructure, a commitment that may cost $1 trillion over the next 30 years, according to the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. China's new generation of mobile missiles are outfitted with multiple warheads and penetration aids, the Pentagon reported to Congress in April. Between March 2014 and March 2015, both Russia and the United States slightly increased their numbers of deployed warheads, and both countries are working on new long-range strike bombers. France is developing a new cruise missile and Britain will decide in the near future whether to replace its fleet of nuclear-armed submarines.

These powers, collectively known as the P5 (for the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council), were on the defensive for much of the conference, which shifted between closed-door squabbles over document text and open committee debates on disarmament, nonproliferation and the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. A coalition of 107 countries led by Austria closed ranks around a "humanitarian pledge" to "fill the legal gap" in the treaty by pursuing a prohibition of the possession and use of nuclear weapons. The U.S. delegation opposes such a ban and argued during the conference that it would fracture the treaty, which is based on consensus.

"If for security reasons the [P5] feel that they must be armed with nuclear weapons, what about other countries in similar situations?" asked South African delegate Abdul Samad Minty during a May 16 session. "Do we think that the global situation is such that no other country would ever aspire to nuclear weapons to provide security for themselves, when the five tell us that it is absolutely correct to possess nuclear weapons for their security?"

The P5 nations maintained that they are fully compliant with the treaty and resisted the establishment of any concrete timetable for disarmament — a major sticking point for the Non-Aligned Movement of 100-plus countries, chaired at the conference by Iran.

"We continue to believe that an incremental, step-by-step approach is the only practical option for making progress towards nuclear disarmament, while upholding global strategic security and stability," the P5 countries said in a joint statement early in the conference.

Over the ensuing weeks, the United States laid out evidence of its own compliance: a stockpile that has been slashed by 85 percent from its Cold War height, the conversion of 500 metric tons of Russian highly-enriched uranium into power-reactor fuel, and a pledge to seek funding to accelerate the dismantlement of retired warheads by 20 percent (though last week the House of Representatives approved a budget cap on unilateral dismantlement).

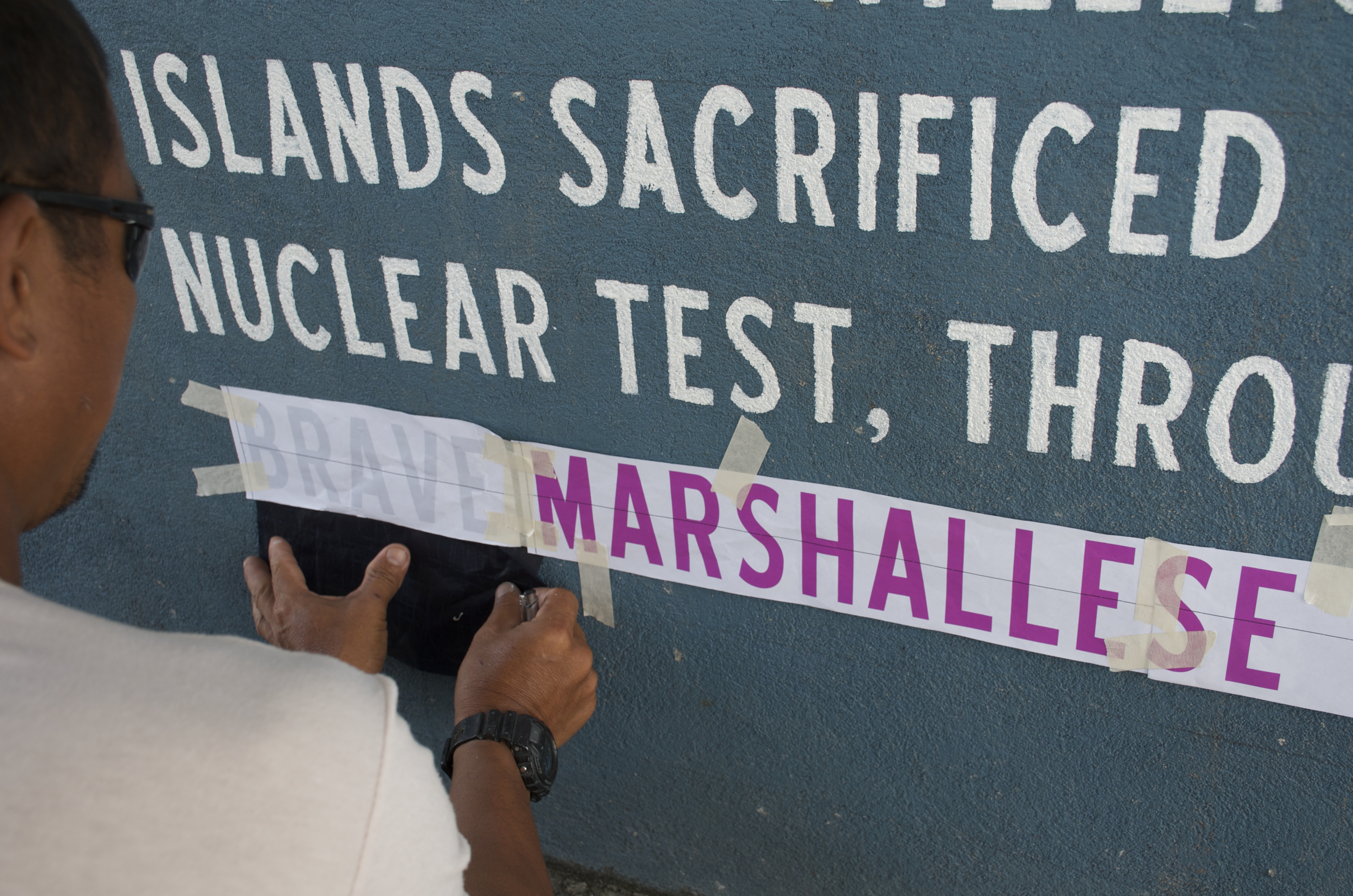

None of these efforts have quelled an uprising among civil society groups and the coalition of 107 states, which are seeking to reframe the disarmament debate as an urgent matter of safety, morality and humanitarian law. Anti-nuclear campaigners, angered by the perceived weakness of the outcome document, view the humanitarian pledge as the most significant result of the troubled diplomatic process.

"It has been made clear that the nuclear-weapon states are not interested in making any new commitments to disarmament, so now it is up to the rest of the world to start a process to prohibit nuclear weapons by the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" in August, said Beatrice Fihn, executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a coalition of 400 nongovernmental organizations in 95 countries.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the number of states who are party to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The number is 191, not 189. This version has been corrected.