MANILA, Philippines—It has been two years since Amelia’s* three sons were taken into foster care.

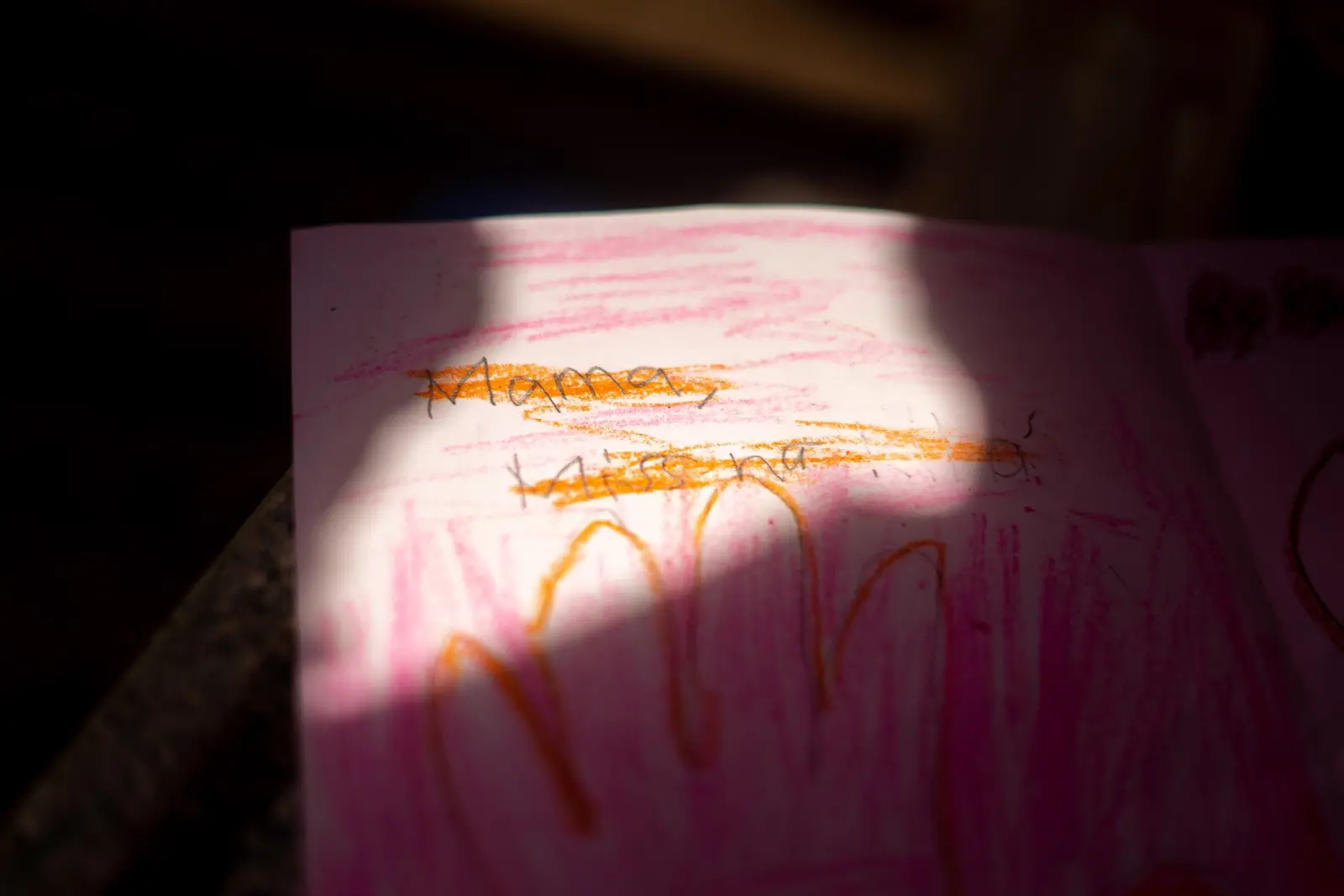

She wants to see them badly, but she can't because she cannot afford to make the trip to where they are. "Their tenderness, their hugs… I can’t experience those anymore," the 28-year-old mother says in Filipino.

Hers is but one story among countless Filipino women who have had to give up their kids to foster care in order for their children to have a better life.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Many others are not so lucky: They were forced to give up their children entirely or abandon them.

According to Department of Social Welfare and Development data, there were 1,999 abandoned and 3,344 neglected Filipino children from 2016 to 2021.

While a family remains the best environment for a child, says registered child psychologist Aileen Sison, not all families and parents are capable of providing the care and support their children need — as was the case with Amelia.

Two years ago, Amelia was stabbed in the chest and back by her then-husband Danilo* due to jealousy.

"I was 50-50 back then. I don’t know how I survived."

The pain from her wounds left her unfit to work as a dishwasher at the fish port near their home in Smokey Mountain, Tondo.

Once she was discharged from the hospital, Amelia lined up to receive a cash grant of P8,000, which was a government-provided emergency subsidy under the Social Amelioration Program or SAP, given to Filipinos who lost their jobs or sources of income during the pandemic.

Still, this was not enough to get her by as jobs were scarce.

"I went to the nearby market to look for a job but no one would take me in," Amelia, who has yet to find employment, says.

More data from the DSWD says that many biological parents are left with no choice but to surrender their children to alternative parental care—like foster care—or abandon them entirely, due to factors such as extreme poverty, single parenthood, or abuse.

In Amelia’s case, her stabbing was not the first time that her husband was violent towards her. That began when she gave birth to her eldest child.

Danilo accused her of being in a relationship with someone else and would beat her regularly. He would also leave all the paid work, housework, and carework to his wife, while he spent his time drinking.

This cycle of abuse is one that Charity Graff has seen time and again.

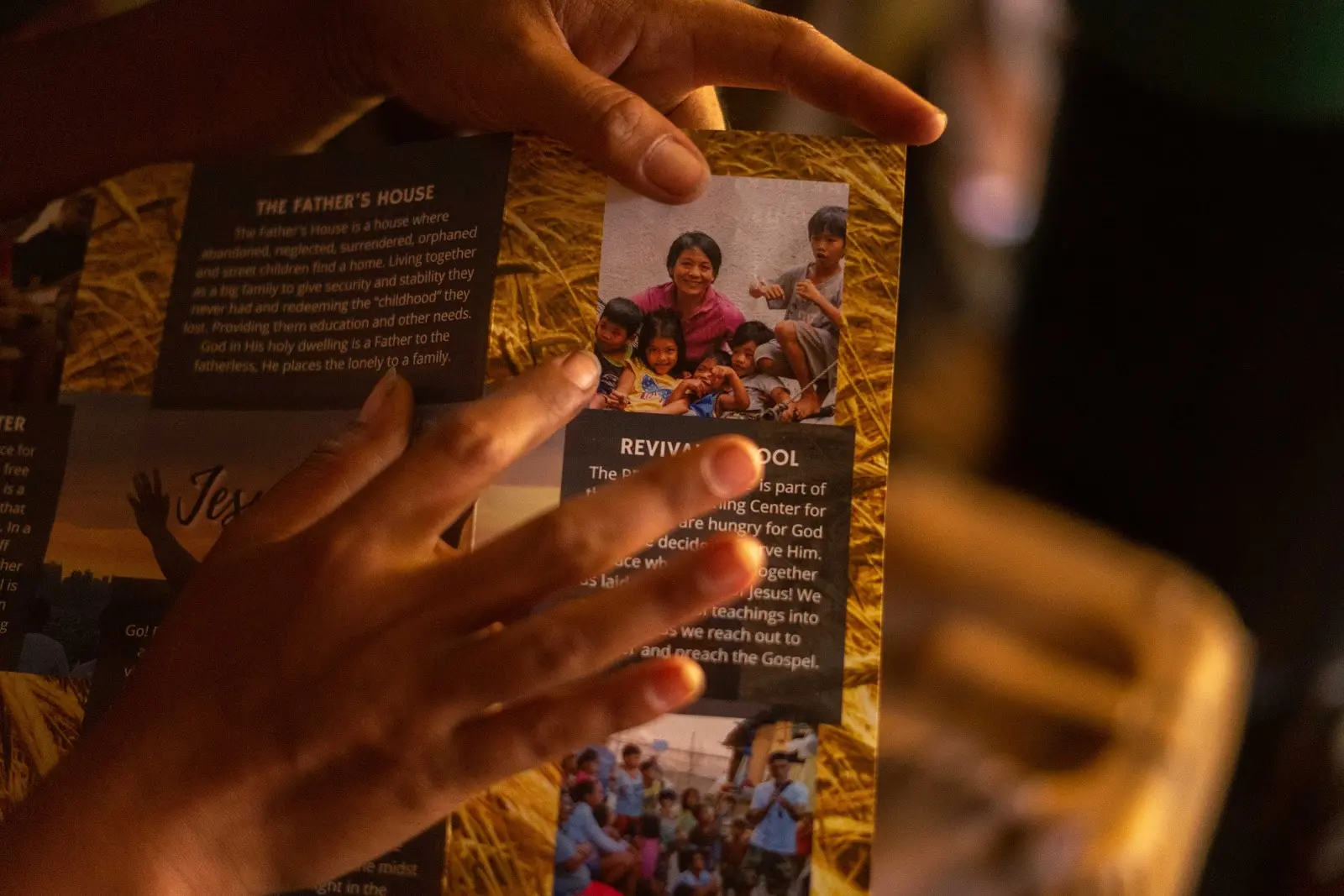

Graff, executive director of Gentle Hands, a privately-run childcare agency in Cubao, believes the problem goes deeper than just abandoning a child.

"Well, it’s not that [women are] just looking for sex. It’s that they end up looking for some way to survive: ‘You can provide for me.’ [Because they] don’t practice good birth control, [they] end up with babies; [and] the babies were not necessarily conceived out of a loving, healthy relationship."

"So it’s easy for them to say, 'Keep the baby, I’ll just go somewhere else'," she says, adding this scenario happens "all the time."

In the end, it’s the children who bear the brunt of the situation.

Government 'safety nets'

With gender-based violence and child abandonment remaining huge problems for Philippine society, a question that begs to be answered is what action the government is taking.

Social safety nets—like the ‘Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program’ or 4P’s—exist, and could have helped prevent circumstances like Amelia’s from happening in the first place.

A 2015 study conducted by the World Bank says that the 4Ps resulted "in improved education and health outcomes among beneficiaries", and that the program "helped reduce short-term poverty and food poverty at the national scale."

Programs like 4Ps are meant for "the poorest of the poor", but getting in can be a challenge and not everyone can be a beneficiary.

For Amelia to have qualified for the 4Ps cash grant, her children must be in their preschool or elementary classes 85% of the time, and they must receive regular preventive health check ups and vaccines—qualifications out of reach of someone in her situation who was always busy with work and housework.

Data from the Center for Women’s Resources also paints a stark picture. According to 2020 figures, CWR said 19.54 million women in the Philippines are considered "economically insecure", and women from the informal economy "continue to experience lack of social protection measures and are most vulnerable to abuses".

Assistance from the local government unit could also have been a factor in keeping parents from giving up their children, says social worker Carol Lara, who has been in social work for more than three decades.

"As an LGU, the first thing to do is to explore options to keep the child within the family. Maybe you can help the family or relative, [depending on the available services of the LGU]," she says.

LGU interventions could include giving seminars or funding the parents’ livelihood, all while making sure that there is significant development in the social and economic aspect of the parents’ lives.

In Amelia’s case, interventions from the local officials for gender-based violence could have meant that her incident could have been avoided entirely. But the response from the LGU in those instances was that they should resolve theior domestic issues on their own.

Hope for reunion

"December is nearing," Amelia says. "In December, I want us all to be together, since it’s Christmas. Families should be complete rather than apart."

While being away from her boys is not ideal, Amelia believes it was the best decision for her children.

"We just do video calls, when they have time," she says.

"My son Derek* now speaks in straight sentences. And you’ll get a nosebleed from my son Daniel*. He can now speak in straight English. I told myself, 'This kid is good'," she says.

Her only obstacle now is how she can get them back.

She is adamant that she does not want to give her children up for adoption. However, the longer she remains jobless, the longer her children are separated from her.

"If I could get at least two of my sons, I’d be okay with that," she says.

* Names have been changed for subjects' privacy and safety