In the hilly southwestern region of Uganda, a life-line river of about five million people has had up to 80 percent of its water dry up. The national environment watchdog – NEMA says the prime factor drying Rwizi River is illegal land acquisition in its catchment area.

Jeconious Musingwire, an environmental scientist and NEMA’s manager for south western Uganda says, “200 people” including investors, “have illegally acquired over 500 hectares of land along river Rwizi.”

They “cleared off buffer wetlands” that used to trap pollution into the river, “impairing microclimate of the area” and the “water quality,” he said.

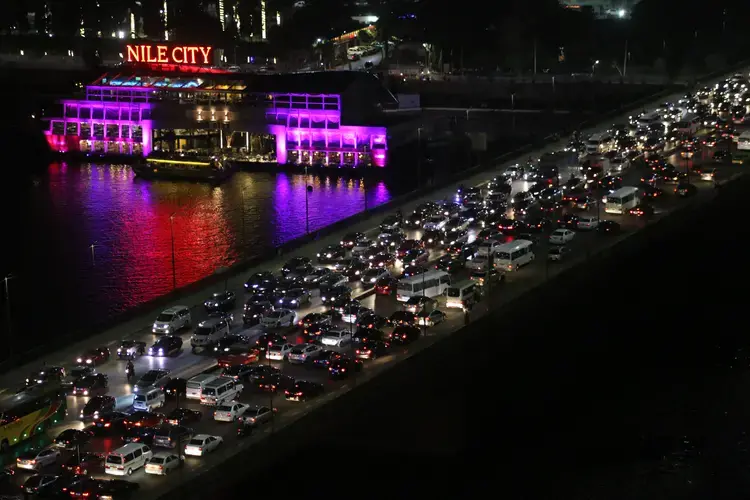

According to Jeconious, this dilemma is not unique with Rwizi River. He says river Nile and several other rivers in developing countries face the same problem.

“Land deals along river Nile could easily impair its recharging potential if water abstraction is not regulated.”

River Nile has a mean annual flow of 84 billion cubic meters of water measured at Aswan Dam in Egypt.

Up to 10.3 million hectares of land have been acquired by investors in 11 countries that form the Nile basin countries since 2000, according to Angela Harding, data coordinator for Land Matrix Africa team.

Land Matrix is an independent global land monitoring initiative. The Nile basin covers an area of 3.18 million square kilometers, almost 10 percent of the African continent.

These are, “just concluded deals,” says Angela, implying that there could be other land deals underway.

Although there are a few new land grab deals being signed now, and others being abandoned in countries such as Ethiopia, “more of the older deals are being brought under implementation,” she noted.

Generally most deals are leases, forest concessions and very few are outright purchases. Data from Land Matrix initiative shows South Sudan as the biggest victim of land grabbing in the Nile basin.

Several countries have acquired land in the Nile Basin. These range from countries outside of Africa investing in land, as well as those investors registered within Africa also known as regional investors. The Land matrix website shows some of these countries to include Austria, Belgium, Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Israel, Norway, Saudi Arabia, UK, USA and others.

Most of these investors are acquiring land for growing food crops, non-food agri-commodities such as tobacco, biofuels, livestock and timber plantation.

Land grabs or water grabs?

What is more surprising is that most land deals in the Nile basin are actually water deals although a few are oil and other mineral grabs.

Tom Lavers, lecturer in politics and development at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute says these are for the most part not investments targeting land but targeting water and land.

According to Tom, agricultural production in much of the Nile basin is at the, very least more reliable and more productive in terms of multiple harvests, per year if land has a water source for irrigation.

This, he notes, is the reason why, “a great many investments combine the two whether these are state-led e.g. Tana-Beles or private investors Karuturi and others.”

Tana-Beles is a large irrigation scheme next to Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Karuturi is an Indian investor who secured the largest lease from the Ethiopian government for 100k ha in Gambella. The Karuturi investment subsequently failed.

Likewise, Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink-Seyoum, senior Lecturer in water governance at IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands recounts that often the dispossession of land is associated not just with land but with other resources that are available in the land or near it.

“I do not think that many of the legal and illegal dispossessions of land are purely related to the soil. In soil, there is always water available and most of these lands are taken away for agriculture purposes,” she said.

However a Kemerink-Seyoum and Tom acknowledge that there are other cases which are actually not a water grab.

Tom cites the example of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) attempt to control water, without a direct link to land and agriculture, although there are claims that it will mediate the Nile’s flow and thereby facilitate irrigated agriculture in the Sudan.

In Sudan for example, land and water grabbing are mainly visible in the state of Khartoum, River Nile and Northern where Nile passes or has tributaries.

Stefano Turrini, a scholar involved in the study of agricultural development in Sudanese drylands and a Phd candidate in Geography at Padova University in Italy says, “since the 2000s, these states of Sudan have experienced expansion of agriculture projects for exports.”

Massive appearance of foreign agricultural investments in Sudan started in the early 2000s, when the regime began offering land and water at favourable conditions to the Gulf countries according to Stefano.

“These (Gulf) countries were starting to experience the reduction of their water resources, due to the excessive over-use,” Stefano narrates further noting that, “their domestic agricultural production needed to be outsourced.”

The large-scale projects Stefano examined were carried out primarily for the agro-industrial production of alfalfa (Medicago Sativa). The fodder is mainly exported to Saudi Arabia and UAE for industrial farms and animal consumption.

Stefano believes the biggest acquisition of land in Sudan is that of Moawia Elberier, a multinational conglomerate of 30 companies.

“Moawia could potentially cultivate 480,000 feddans. Yet currently, projects activated by Moawia do not fully cover the available extension and are relatively small,” he notes.

What do land grabs mean to local people?

In most cases, the grabbed land was originally being used by the local people for agricultural and pastoral purposes. Therefore, the establishment of investment project reduces the availability of the local people’s space for economic activities according to Stefano.

He further notes that due to reduction of land for local farmers, conflicts arise between tribes and villagers over the control of land and water.

Towards Sustainable Solutions

Jeconious Musingwire insists that governments in the Nile basin must invest in technologies that could tell how much water is extracted from the Nile to be able to tell when the recharge potential of the river is impaired.

Such technology would help to estimate the amount of water required to bring into production all the land in the Nile basin that has been transferred to investors.

For example, Water scientists at IHE Delft in the Netherlands are developing ground-breaking open access systems for water accounting of transboundary river basins such as Nile basin.

Prof. Dr. Yasir Mohamed, Professor of Water Resources Management at IHE Delft says “theoretically and practically it is possible to map vegetation on the ground by satellite. This includes both irrigated and rain fed crops. “

He also narrates that theoretically it is also possible to know which crops are grown, and how would be the production, though “practically needs a lot of ground totting to correct and calibrate satellite results.”

And according to Stefano, regional authorities should ask investors to provide compensations. “These are often in form of goods and services: a school, a mosque, a clinic, temporary and/or payment to access wells. Offering jobs should be part of the compensation,” maintains Stefano.