Hun Sen, whose Cambodian People’s Party took every seat in the national assembly in last month’s elections, is the world’s longest-serving prime minister (since 1985). His recent electoral victory was assured in November 2017, when Cambodia’s Supreme Court dissolved the main opposition party after the government filed a lawsuit accusing it of conspiring with foreign powers to stage a revolution. Forty years ago Hun Sen was a Khmer Rouge battalion commander. Fearing a purge, he fled to Vietnam in 1977; he returned in 1979 with Cambodian rebel forces and the Vietnamese Army which overthrew Pol Pot’s regime.

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia was set up in 1997 to try ‘the most senior’ surviving Khmer Rouge leaders, or those ‘who were most responsible’ for the atrocities committed under Pol Pot. The ECCC is a hybrid court, with both Cambodian and international prosecutors, defence lawyers and judges. The first case opened in 2007; only ten people have so far been indicted or investigated. Three have been found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment: Kaing Guek Eav, also known as ‘Comrade Duch’, who ran S-21, the former school in central Phnom Penh that was converted into a concentration camp where at least 12,000 people were tortured and killed; Nuon Chea, Pol Pot’s deputy; and Khieu Samphan, the official head of state. Proceedings against three others have been dropped because of their death or illness.

In 1998, Hun Sen gave a total amnesty to Khmer Rouge hold-outs if they would join him. He called this a ‘win-win policy’. ‘The trial is going badly because Pol Pot’s people are in the government now, and spoiling it, and then hiding,’ I was told by a man whose father had been killed by the Khmer Rouge. He named someone in his village who had been a Khmer Rouge official and had committed crimes known to the locals. ‘He says he was acting under orders. No effort has been made to find the person who gave him the orders.’

According to the court’s most recent quarterly ‘completion plan’, from June 2018, the current caseload – involving the remaining four suspects – will finish by the end of 2020; no further cases or suspects are identified. (Hun Sen told Ban Ki-moon, the UN secretary general, in 2010 that he wouldn’t allow the court to proceed beyond its second case, against Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.)

There have been differences of interpretation between the Cambodian and international lawyers as to whether the final cases can be tried at the ECCC. The international co-prosecutor moved to bring a case against Im Cheam, allegedly responsible for forced labour camps, prisons and execution sites, on whose watch there were said to have been widespread purges and disappearances, enslavement and torture, with victims numbering in the tens of thousands. The Cambodian co-prosecutor, however, declined to pursue it. The pre-trial judges also disagreed; once again, the split was along Cambodian/international lines.

I asked Cóman Kenny, the assistant international co-prosecutor, what the difference might be between the case against Duch and the case against Im Cheam, when both appeared to be responsible for comparable crimes. ‘The ECCC’s statute doesn’t actually define the jurisdictional thresholds of “senior leaders” or those “most responsible”, so whether a suspect is within the court’s remit is a discretionary decision for the judges,’ he told me. ‘S-21, which Duch headed, has a highly symbolic place in Cambodian memory, and the killing there was particularly intensive relative to its small size. Im Cheam’s alleged crimes were distributed over a much larger area. At any other international criminal tribunal established to date, a case of the scope and gravity of the Im Chaem case would be among the largest, if tried.’

Meas Muth was charged with genocide and crimes against humanity. When the preliminary investigation concluded, the co-prosecutors made separate final submissions: the international lawyer argued that Muth should be indicted; but the Cambodian co-prosecutor, who had declined to participate in the investigation, argued that the case should be dismissed. There are similar disagreements over the cases against Yim Tith and Ao An, who face the same charges. This month, in the case against Ao An, the co-investigating judges issued opposing closing orders for the first time in the court’s history. Four international judges have resigned since 2010.

Pheaktra Neth, the ECCC’s senior press officer, described a busy programme of outreach activities – including tours to S-21 and visits from community delegations to the tribunal’s large public gallery – that are part of the court’s ‘moral reparation’ to Khmer Rouge victims. People in rural communities told me they’d received an official invitation to attend court proceedings for a couple of days, but the journey time meant spending around a week away from their farms, which they couldn’t afford. For those who accepted the invitation, the court proceedings were difficult to follow: they had no experience of a trial; the language was technical and reaching them through simultaneous interpretation that wasn’t always immediately clear; they were illiterate and so had few sources for background information; the short observation period wasn’t enough for them to get their bearings.

People seemed more engaged by Radio Free Asia’s regular – and critical – reporting on the tribunal during its twice daily Khmer-language programme. But the station had to close its Phnom Penh bureau in September 2017, a casualty of the government crackdown on independent media in the run-up to the election.

‘It looks like a court but is more like a children’s game where they hide from each other,’ I was told by a man whose brother had been killed by the Khmer Rouge. ‘They are searching for “the responsible person”, but no one knows who that is. We hoped the international judges and lawyers might be able to find someone, but they haven’t either.’

‘The trial is like a play,’ another man complained. ‘Everyone there is reading from a script and playing a part. It’s just a performance.’ (Khieu’s international defence lawyer made a similar comparison when I met him in Paris seven years ago.)

The court’s activities – costing, to date, around $320 million – have been funded in part by the Cambodian government, but most of the money has come from international donors (including Japan, the US, Australia, the EU and Microsoft). Shortfalls have repeatedly led to the suspension of court proceedings while another round of fundraising takes place. China, notably, hasn’t contributed anything at all, although it is now Cambodia’s largest foreign investor. As its economic and military support grows, Hun Sen will be less obliged to accommodate the expectations of Western donors. China was the only foreign power to endorse the recent election.

I asked the villagers I spoke with how they would feel if the tribunal were to close down. All of them thought ‘it should continue until justice is done and the responsible people are found.’ Apart from Pheaktra, all the Cambodians I spoke to, including my interpreter, asked for their identities to be withheld because they were nervous of government retribution.

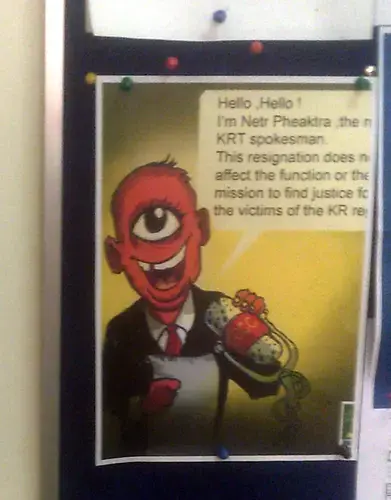

I asked Pheaktra what he would change about the tribunal if he could. ‘I don’t have any criticisms of the court because everything is going well,’ he said. ‘We are actively completing the mission of the court, to bring justice for the victims.’ He had pinned up in his office a cartoon of himself, one-eyed and smiling broadly, reading an official statement: ‘This resignation does not affect the function or the mission [of the tribunal] to find justice for the victims of the KR regime.’ I asked him about it. He lit up with amusement. ‘It was published by the opposition party on my first day in this job. My name means “eye” in Khmer, so they drew me with one eye. They said I am claiming that everything is working perfectly at the tribunal and there will be justice for Khmer Rouge victims.’ He gave a small shrug. ‘They disagree.’