Last April, Mohammad Farid Hamidi, Afghanistan's 49-year-old attorney general, made an unprecedented pledge: From eight in the morning until eight in the evening each Monday, he would meet with anyone seeking legal counsel. On some days, this meant seeing as many as 200 petitioners. Hamidi, who came into power in April 2016, called the practice morajein-e roz, or the day of the petitioners.

On a brisk Monday morning last November, scores of Afghans meandered outside the attorney general's office in downtown Kabul, hoping for an audience with Hamidi. Some dressed in western-style suits befitting the urban upper middle class, others in more traditional garb. A handful of the men who showed up worked down the street from the building, while others had traveled for days. Others still had packed snacks or lugged caches of paperwork that had accumulated over the course of their legal battles with venal local politicians, unjust bosses, or bullying neighbors.

The building had been recently renovated to symbolically mark the transition from the previous attorney general, whose tenure had been marred by accusations of corruption. Balustrades were still wet with paint, and workmen were pushing wheelbarrows carrying computers, the building's first ever.

Inside, Hamidi's office, packed with visitors, was stifling. His cluttered, expansive desk and the dark mahogany wainscoting gave the room the asphyxiating feel of a winter cabin. Sitting behind the desk, he listened closely, his handsome, wide-open face and striking eyebrows focused on the petitioners. (There were no tea breaks, as Mondays were strictly for business.) A young man asked for his help in settling a family dispute. A woman sought guidance on a sexual harassment suit. A well-kept older woman protested that she had been fired from her job as a low-level civil servant after exposing the office's internal corruption. A soft-spoken younger prosecutor asked to be transferred to Kabul; her conservative colleagues in the rural east were not amenable to her working there, she said.

Hamidi asked questions and took occasional notes. Many of his visitors betrayed their ignorance of the law, or of the limits of his power. He knew that the uneducated and the poor often faced the steepest disadvantages in the justice system, and were often unable to serve as their own best advocates.

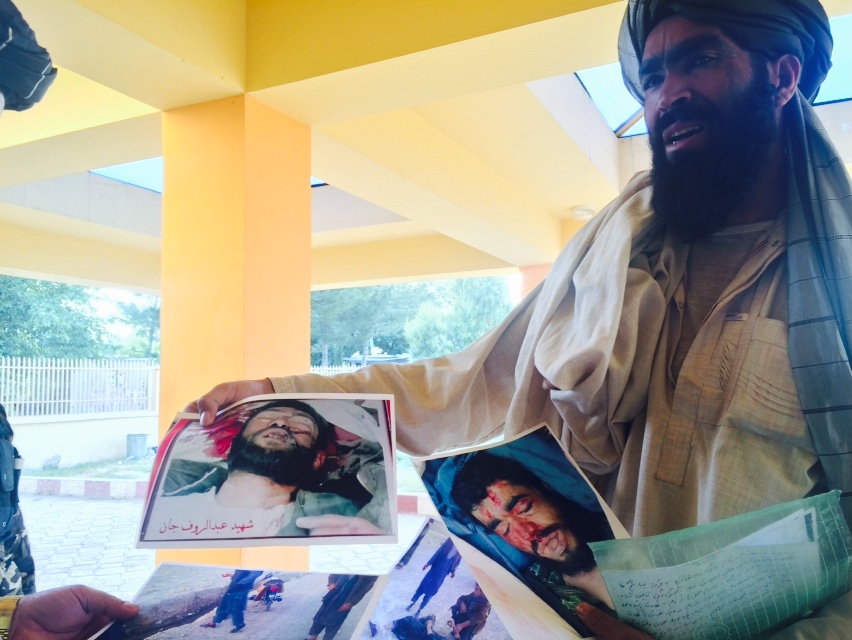

Around mid-morning, a day laborer named Abdul Rahim walked in to see Hamidi, carrying with him a tattered folder crammed with paperwork. He had arrived in Kabul after traveling in a shared taxi for hours from Kapisa, a province some 65 miles away. He'd heard about Hamidi on television, and liked what the big man had to say about curbing the culture of impunity that allowed corruption to fester among the country's elites.

Rahim, who was "approximately 60," hoped Hamidi could help settle a land dispute that predated even the Taliban regime. The land in question, purchased in 1984, had been taken unlawfully by a powerful, distant cousin, he said. It was now worth $20,000, and he wanted it back. He had followed the official channels, bringing the case before the local court, the appeals court, then the supreme court, all to no avail.

After listening to Rahim, Hamidi handed him a letter that would allow him to restart legal proceedings. "The saranwal, he's a good guy," Rahim said, using the Dari word for prosecutor. "All the people of Afghanistan would agree with me."

The hope was that this one-to-one outreach would help Hamidi gain the trust of ordinary Afghans, those exploited by an elite class that has gotten fat off of the aid money that has flooded the country since the U.S.-led invasion in 2001 that ousted the Taliban. But in a country plagued by dysfunctional institutions, the reform approach has its limits. Meanwhile, there is a rising concern that making an enemy of Afghanistan's most powerful—those who have profited off the war economy—may doom him just as he's getting started.

Hamidi is a police-academy graduate whose work as a human rights commissioner won him a strong recommendation from President Ashraf Ghani, who, in one of his first official acts, nominated him to lead the attorney general's office. The parliament confirmed him, by a vote of 200-19. From the beginning, he was feted as a star of Ghani's reform agenda. Nader Nadery, a senior advisor to the president, told me there were worries over whether he could meet the impossibly high expectations. Then, "when he started bringing the first set of reforms, the president became more and more confident. [Hamidi] would pass by and the president would point to him and tell me, 'I am proud of him,'" Nadery said.

Early in his tenure, Hamidi opened in-house investigations into other prosecutors who had been accused of taking bribes. Nadery, who conducted an assessment into the state of the attorney general's office for Ghani, called it "the nastiest, dirtiest place you could think of." There was systemic corruption throughout the attorney general's office, he said.

Hamidi said that his investigations into the attorney general's office resulted in the firings of 30 of the old guard. Many had allegedly been permitted to carry on corrupt practices under Hamidi's predecessor, Mohammad Ishaq Aloko, who is closely aligned with the former President Hamid Karzai; his name is still linked to the Kabul Bank scandal of 2010 and 2011, which saw nearly $1 billion dollars disappear in faulty loans. (Karzai never allowed auditors to investigate his own foreign holdings.) Hamidi also told me that he has banned some 3,000 people with pending corruption cases against them from traveling abroad. This is in addition to the 125 he has coaxed into early retirement and the 250 he has newly hired. He has also pushed for higher educational standards and salary increases for recruits, as a deterrent against bribes.

In recent months, Hamidi has been building on his momentum by trying to prosecute the kinds of strongmen who have evaded the law. In January 2017, Hamidi went after Afghanistan's vice president, whose bodyguards allegedly raped and tortured a political rival. Ahmad Ishchi, the victim, has accused Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum of kidnapping, beating, and deputizing his bodyguards to sexually assault him. While Hamidi has ordered the arrest of nine of the bodyguards and Dostum remains under investigation, it is unclear whether anyone will be prosecuted in the case.

Targeting Dostum represented an escalation for Hamidi, from cleaning house and dealing with financial impropriety to taking on some of the most powerful political figures in Afghanistan. Hamidi certainly "created a buzz," Nadery said. But his efforts have also met resistance, said Yama Tourabi of the Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee, an internationally funded group that is conducting its own audit on the attorney general's office. "His political will is clear, but there are signs of resistance in his office," Tourabi said. He added, "I wouldn't say he cleaned the house because I don't think you can clean up [the attorney general's office]."

Above all else, Hamidi is most critical of the failed legacy of 16 years of foreign aid money that streamed into government coffers unimpeded and without effective oversight, a force that threatens to capsize the already fragile state. Nearly $1 trillion dollars in war and Overseas Contingency Operations funding has been spent on the wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan by the Pentagon, State Department, and USAID—a staggering sum, considering that it hasn't prevented the Taliban from regaining a substantial foothold in the country. Meanwhile, fighters claiming allegiance to ISIS are also operating there, and staged a spectacular attack on a military hospital in Kabul on Wednesday. "The foreigners made ambitious plans without looking at the capacity so nothing was implemented," Hamidi told me.

There have been some changes in recent years. The United States Agency for International Development, for one, had earmarked $26 million to track where its funds were going, in addition to the $87 million it was already spending on anti-corruption efforts. But this number is paltry, Hamidi said, when considering that as much as 75 percent of the entire budget for Afghanistan came from aid, much of it spent without any accountability measures.

Despite Hamidi's efforts, in September 2016, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, the auditing arm of the U.S. mission in Afghanistan, found that corruption remained the norm throughout the government. President Ghani alone, out of 83 senior officials, fully complied with financial disclosure laws, SIGAR found.

For now, Hamidi remains the people's prosecutor. This sort of personalized politics will surely endear him to Afghans, but it may be an unsustainable project in the end. It's doubtful that his efforts will change much, so long as Afghanistan's sclerotic, toxic institutions are allowed to continue conducting business as usual. In fact, building a justice system around one-to-one outreach will only further warp that system, forcing it to rely on the mission of a single, charismatic, crusading personality, rather than the institution he was meant to fix.

"If you look at the senior management," according to Seema Ghani, an anti-corruption activist not related to the president, "half are corrupt and the other are incapable." Ghani said that Hamidi had been "too soft," and was being "careful with his future." The portrait of him as the savior, she said, wasn't entirely accurate. When posed this assessment, Tourabi shrugged and replied, "What can you do? He is the best we have for this job."