Last year, while working on a story about child care, Alice Proujansky and the writer Alissa Quart met Blanca Conde, a nanny from Paraguay, who was living in Queens and working in Manhattan.

Conde's story was, on the surface, typical of many immigrants: She worked long hours and was the financial caregiver for her family who remained in Paraguay, including her son, Guido, from whom she had been living apart for a decade.

Although they were happy to have met Conde, Proujansky said the story felt dark since Conde often spoke about being reunited with Guido. "It sounded like a fantasy," Proujansky said. A few years earlier, Guido had tried to live with his mother but returned to Paraguay soon thereafter since the demands of Conde's job made it too difficult for her to take care of her own child.

Shortly after working on the story, Proujansky received a text from Conde saying Guido would be permanently moving to New York to live with her; it felt like a happy ending to Proujansky's story.

But Guido's arrival took the story in a new direction, specifically, how would Conde, as a single mother, be able to help Guido navigate the complicated systems of middle-class America, one Proujansky said Guido was "sort of dropped into."

Back in Paraguay, Conde's mother took care of Guido, a common scenario for many immigrant families separated by long distances. Guido was doing well there, exceling at soccer, taking swimming lessons, and attending a private school that Conde's salary was able to cover. But in New York, he was now living a much more complicated life, starting school in the middle of the year with limited language skills while sharing a tiny apartment with his mother who worked long hours.

While they were living apart, Conde was still an invested parent, texting and calling often. "He would ask if he could have an ice cream and was told he could if he did his homework," Proujansky recalled. But rewarding good behavior from a distance is one thing, trying to get your child into the best high school in New York is something completely different.

"He was going from being a middle-class kid to being a poor immigrant kid in Queens whose mom was working long hours," Proujansky said. "Her abilities were all about working harder, so when he would struggle she would tell him to do more homework, work harder, and that's a good skill if you're trying to make money to send home. But to become a middle class American he needed skills Blanca didn't have, like which person to talk with to get into an after school program and how to choose from New York City's 400 public high schools."

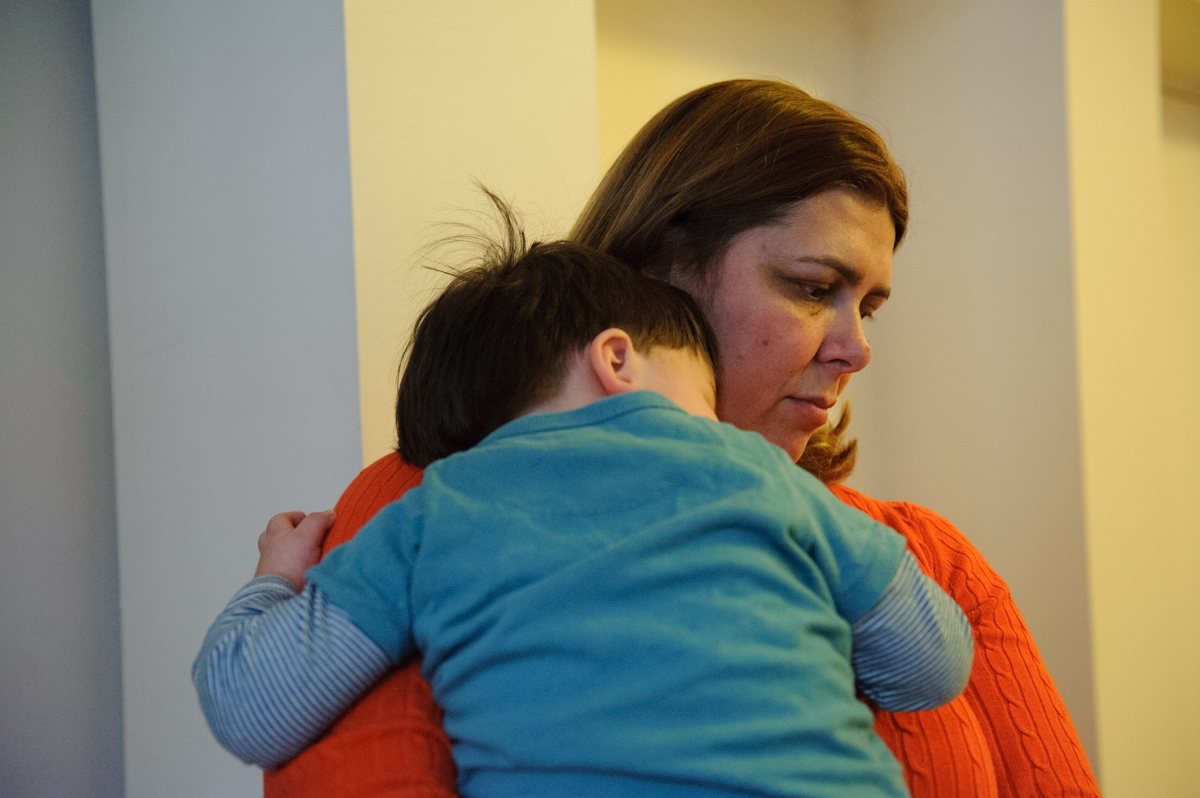

Proujansky documented those adjustments from March through December when she would visit Blanca and Guido both at home and in their school and work environments. Although there were struggles, she said the change in Blanca once Guido arrived was remarkable.

"For families who rely on remittances, the definition of family isn't about nuclear units. As the person who could earn the highest wage, Blanca looked at what was best for her family and decided to go where she was best able to support them, although it meant missing Guido's childhood. It was clear how painful this was for Blanca, seeing how depressed she was before he came to New York and how much better she felt when he was here—it was a huge sacrifice."

While Proujansky was working on the series, she had difficulty finding reliable and affordable day care for her 2-year-old son. The demands of a culture that requires longer working hours and greater accessibility trickle down to child care workers, who must also juggle responsibilities, often working under meager wages.

"People often talk about how expensive child care is and I can agree form personal experience that it is, but at the same time it's too cheap because it doesn't allow many child care workers to make a living wage," Proujansky said.

It's a cycle Proujansky says is rooted in mixed messages about how we raise our children in America.

"I think our culture both devalues care-taking and puts a really rosy filter on it. As a mother you're supposed to love sacrificing and caring for your kid all the time, but professionals who do that work aren't well compensated financially. Women are encouraged to want to work and have it all but also to feel badly for leaving our kids in childcare, and our cultural hesitation to fully support childcare workers is related to these misgivings we have about working motherhood in general. We are uncomfortable valuing care work because we think it should be given selflessly."