Times Insider explains who we are and what we do, and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together. This article first appeared in the At War newsletter.

At the press room at the U.S. Navy base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, in a decaying hangar, reporters speak ruefully about what has come to be called the Curse of the Curtain-Raiser. In the jargon of journalism, a "curtain raiser" is an article that tells readers what is coming in an engaging, informative way — maybe an election, a playoff game or a congressional hearing of consequence.

But at Guantánamo it is a perilous pursuit. Only the most naïve or optimistic journalist dares to predict what might happen at the place President Barack Obama said he would close, and could not.

In the summer of 2012, for example, the Pentagon brought 20 journalists there for a pretrial hearing in the case against Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four other men accused of conspiring in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. One reporter wrote that the topic would be torture. Another said a challenge to court secrecy was on the agenda. A New Jersey paper wrote that a local couple was traveling there to "stare into the eyes of five men accused of murdering their son and thousands of other 9/11 victims."

None of that happened. First, a train derailed in Maryland, severing secure communications to the courtroom in Cuba, forcing a delay. Then, a storm prompted the Pentagon to evacuate nearly everybody involved in the hearing — 177 people on a single flight to the mainland — leaving the prisoners and soldiers to ride out Hurricane Isaac. But the storm veered north, sparing the base.

That is the thing about reporting on Guantánamo: Write about it, and it will not happen.

In 2016 and 2017, reporters from a half a dozen news outlets wrote that the first man to be waterboarded in the C.I.A. torture program would testify about the conditions at Guantánamo's most clandestine prison, Camp 7. It is three years later, and the prisoner known as Abu Zubaydah has yet to take the stand.

Sometimes legal strategy or illness derails the schedule. Other times logistics or the weather are to blame. It is never easy to hold a hearing at the Expeditionary Legal Complex, whose courtroom is inside a building encased in corrugated metal on a cracked, obsolete airstrip, with a nearby tent city and trailer park. Last year, a hearing lasted two days because a Marine Corps judge had to be medically evacuated to Florida for emergency eye surgery. It was too much for the Navy's 12-bed base hospital to handle.

So I should have known better in December when I consulted the calendar, counted up 215 scheduled court days and wrote about how 2020 was shaping up to be my nearly nonstop year as a Guantánamo war-court reporter. (Most years I focus as much on the prison and the people as I do on the court.)

There was not a whiff of the coming coronavirus crisis. Nor was there a hint that the 49-year-old career Air Force officer judge who had set an ambitious timetable of hearings toward an early 2021 trial for the Sept. 11 case, would suddenly retire in "the best interests of my family." Yet to happen was a long-serving, 75-year-old capital defender for one of the 9/11 defendants, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, leaving the case on his cardiologist's advice, a separate source of delay.

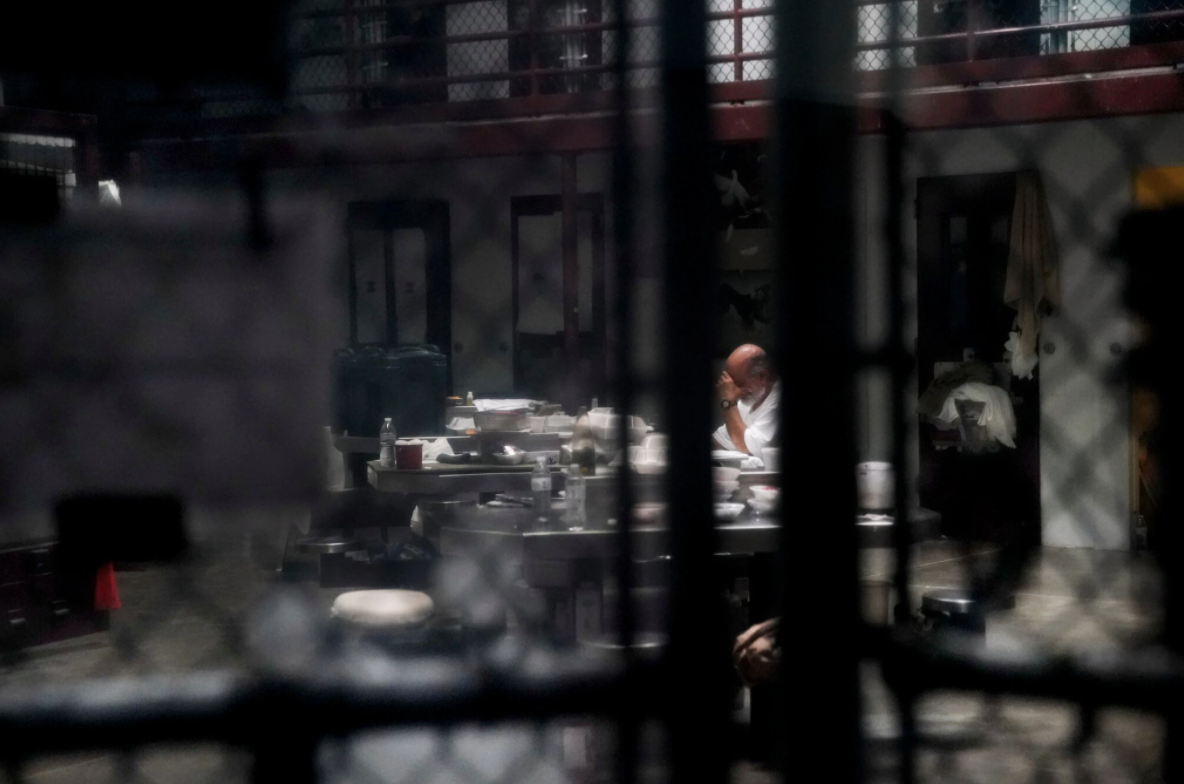

No hearing has been held since late February. No reporter has set foot on the 45-square-mile base of 6,000 residents behind a Cuban minefield, among them 250 school children whose Navy and contractor parents have mostly opted to send them to study at the base school rather than to learn remotely. None of the 40 wartime prisoners there have had an in-person legal meeting since the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic on March 11.

Guantánamo today is in a bit of a mix-and-match existence. The gym, outdoor cinemas and churches are open, with social-distancing policies in place. New soldiers from mostly Army National Guard units still arrive on nine-month tours of duty and are put in isolation for two weeks. But after confirming two Covid-19 cases in March and April, the military is now forbidden from discussing new cases.

Flights are infrequent, except for the twice weekly refrigerator plane that brings fresh fruits and vegetables. Visitors are rare. Judges in the two capital cases — against the men accused of plotting 9/11 and another man accused of conspiring in the U.S.S. Cole bombing, in 2000 — have canceled six scheduled hearings so far. One declared the prison's plan for a 14-day quarantine for newcomers "unduly burdensome."

Life on the base has in some respects reverted to its time as a mostly forgotten backwater before the Marines walked 20 prisoners off a now defunct C-141 Starlifter cargo plane and opened Camp X-Ray on Jan. 11, 2002.

Even the International Red Cross, which typically visits Guantánamo four times a year, has canceled its end-of-summer visit — its second cancellation of the pandemic. I mentioned the organization's planned trip in an article in May, maybe tempting the curse.

About that curse: When I first proposed writing about how foolhardy I was to suggest a busy year at the court, which Congress specifically designed without a speedy trial provision, an editor teased: "You don't think you brought on the coronavirus pandemic, do you?" Of course not. But when it comes to predicting what would happen at Guantánamo, I should have known better.