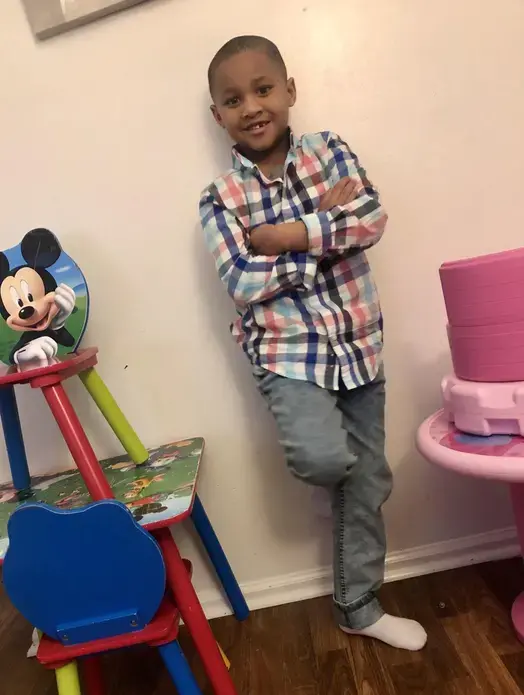

Five-year-old Meegale Hundley can’t wait to race his bike outside.

It’s been 60 days since he’s been allowed to venture outdoors. He hasn’t gone to a park once or even stepped in the backyard at his grandma’s house. But today, he’s so excited he can barely sit still for his school work.

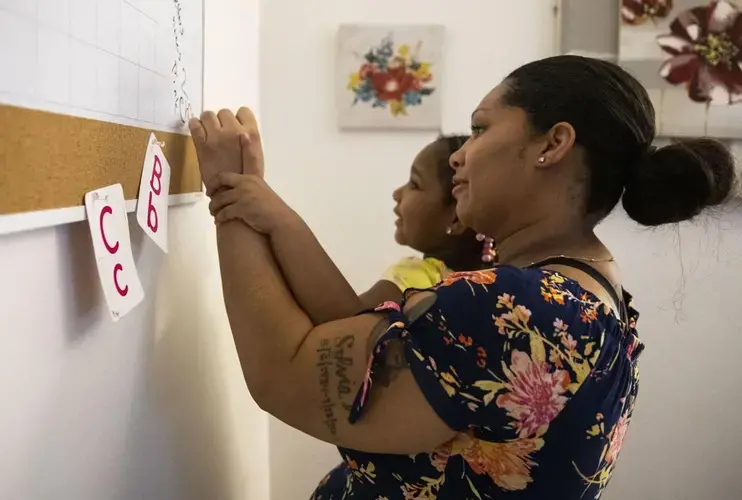

The coronavirus pandemic led to cancelled classes for him and his 4-year-old sister, Madison, since mid-March. His mom, Tyra Johnson, 30, set up a strict daily schedule for their distance learning.

Her babies won’t be falling behind. Meegale is already reading at a first grade level even though he’s in kindergarten. It’s not easy to keep two little ones confined and on task every day for months — especially since Johnson is 32 weeks pregnant and a single mom. Every day, her son and daughter ask when they can see their friends again, when they can go outside and play.

Johnson is terrified of her kids contracting the virus and is keeping them as isolated as possible.

“You don’t want your kids to go outside and then, you know, they get any type of virus,” she said. “It’s just like, I can’t afford it, you know?”

She knows she’s in a high-risk group because of her pregnancy. But even before the COVID-19 pandemic spread, Johnson would drive her children miles away for a play date in a park.

“I don’t allow them to play around here,” she said.

Her apartment sits in Preservation Square, the neighborhood formerly known as O’Fallon Place, in 63106, the ZIP code where people live an average of 18 years fewer than those living eight miles away in Clayton. The ZIP code reflects the generations of systemic racism experienced by African Americans — it has six times the unemployment rate, almost eight times the poverty rate and a quarter of the median income of Clayton in 63105. This public health crisis has affected the black community disproportionately in the city.

In March, Johnson was lying on her bed after getting home from a doctor’s appointment. She heard gunshots outside.

Two of the area’s largest children’s hospitals have seen a startling rise in the number of children shot in recent weeks. Even before the recent spate of shootings, children in St. Louis have been killed at 10 times the national rate for decades, according to a Post-Dispatch analysis of FBI homicide data.

Immediately after hearing the gunfire, Johnson packed up their stuff and headed to her mom’s house in Cahokia. She and the kids shared a pull-out bed in the family room. Her mother works seven days a week, and her sister and niece live there also. Johnson had an hourly job as a clerk in a warehouse before the pandemic. She lost her job when her children could no longer go to school. The family stayed with Tyra’s mom in Cahokia about a month, then headed back to the apartment.

Even when the setting changes, the story of their days is the same.

Johnson wakes up around 7 a.m. She pulls up the verse of the day on her Bible app. She meditates and prays on it for about 15 minutes. Then she appeals directly to God.

“Lord, thank you for waking us up, protecting us and giving us another day’s journey. I’m glad about it. You didn’t have to, but you did. Amen.”

She gets out of bed to get herself ready and make breakfast, usually oatmeal, fruit and turkey bacon for the kids. There’s a board nearby with the home-school daily schedule, down to the minute, on it:

9 am to 9:05: Go over the agenda for the day.

9:05 to 10:15: Circle time, reading, writing and homework packets sent from school.

10:05 to 10:25: Healthy snack and free time.

10:25 to noon: Math and problem solving. Her daughter has a half-hour Zoom class with one of her preschool teachers. Johnson pays $10 a month for the ABC Mouse learning app so her son stays on track academically.

Noon to 1 p.m. Healthy lunch.

1:05 to 2:05: Yoga time.

2:05 to 3:05: Painting and coloring.

3 to 4:05: Special project, which might be one of the crafts she stocked up on from the dollar store.

4:05 to 5:20: Clean up.

5:20 to 5:30: Closing circle, sharing thoughts and ideas from the day.

“You have to be consistent with kids,” she said. “So they don’t slip through the cracks.”

She starts planning dinner in the afternoon. If she’s staying at her mom’s, they will have dinner together around 6:30 p.m. They might get to spend an hour with their grandma, and then it’s time to start getting ready for bed. Each night, there’s a story and prayer.

Johnson opens the Bible again before she goes to bed and asks God for the strength to get through the next day.

“Every day is a challenge,” she said. “It’s like you’re basically hostage in your own home for a period of time...You don’t know when it’s going to end.” Sometimes, she comes to her mom’s house because she gets depressed being alone with her children day after day. She doesn’t like to talk about the baby’s father or the lack of paternal involvement in their lives.

But today is special. They are going to meet one of Meegale’s friends from school, and the boys will get to ride bikes.

“I’m so happy to get out of the house,” he told his mom, the night before. They both miss their lives from before, with teachers and friends and the structured freedom their mom created for them.

If these were normal times, I’d want to be there to see this moment to be able to describe the joy on a kindergartener’s face when he steps into the sun after being confined indoors for two months. But, all our contact has been through the phone. No one can risk exposure to the virus.

In the afternoon, dark clouds passed over the sky. Rain started pouring down as the dreams of the bike ride washed away.

Meegale’s friend still came over to the apartment, and the two rejoiced when they saw each other. They played video games on their tablets.

Meegale hugged his classmate when it was time to leave, and both of Johnson’s children cried when he left.

“Maybe next week,” his mom said. “Maybe next week, you’ll get to go outside.”

The next day, she started feeling contractions. It’s still too early for labor, she thought. She dropped her children off at her older sister’s house in Granite City and headed to the hospital.

The doctors told her she needed to rest. The stress is taking a toll on her health.

They ordered bed rest for the remainder of her pregnancy. She is staying with her older sister.

Unless they are doing schoolwork or eating, the kids play in the same room with her.

The small world they’ve been living in just got a little smaller.

Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a nonprofit racial equity project, is telling the story of families in 63106 over the course of the pandemic. An archive of other family stories is available at beforefergusonbeyondferguson.com.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.

Education Resource

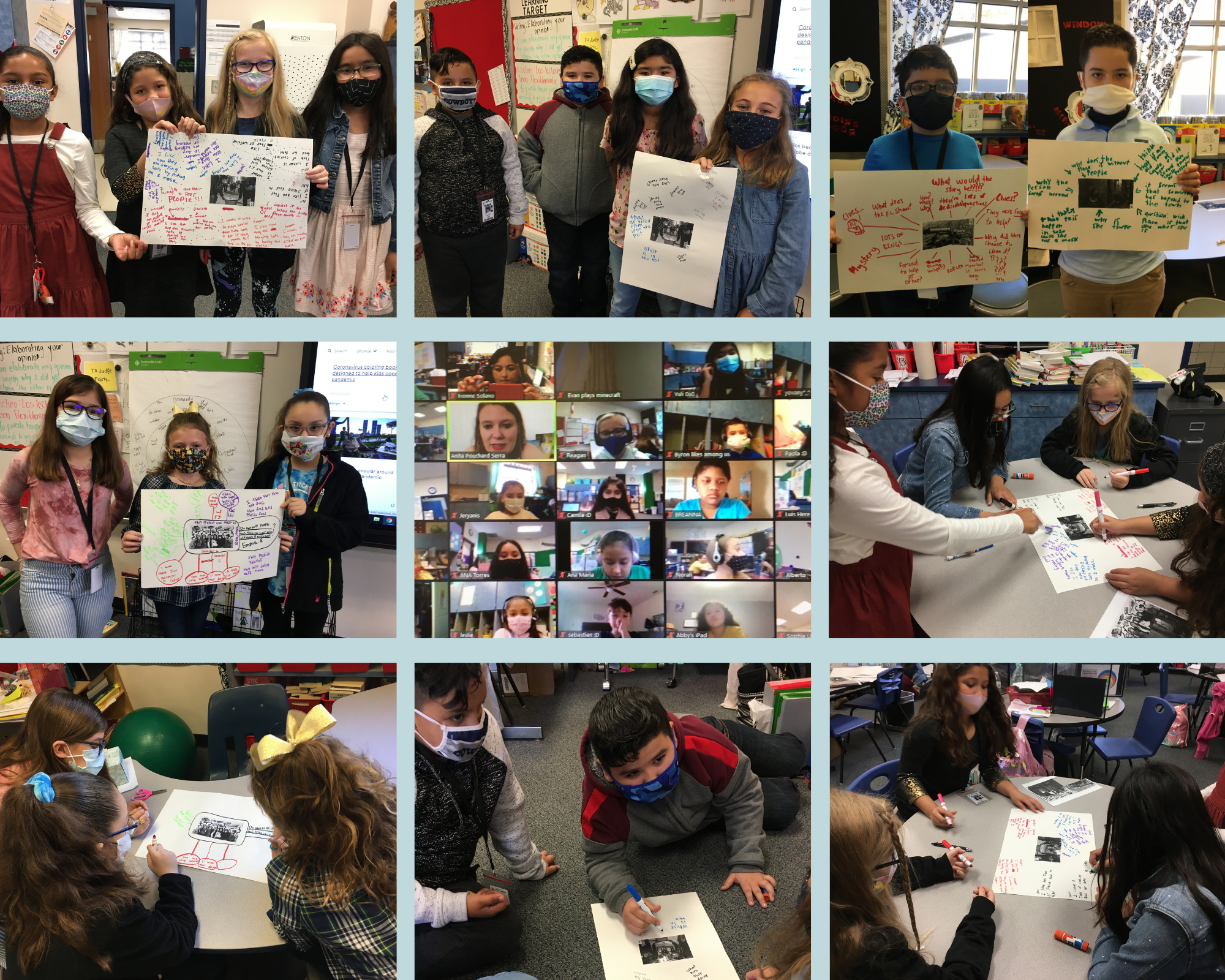

The Impact Of The Pandemic In Local And Global Contexts—Understanding My Role In My Community To Change The World

This unit was created by Ivonne Solano, a fourth grade bilingual teacher in a two-way dual language...