Rodeo Van Bladel started getting that feeling again. The scrawny, balding clerk at window 7 of the California Department of Motor Vehicles (dmv) in Santa Rosa had punched Rodeo’s driver’s license number into a computer, before telling him to wait while he went to check on something.

Rodeo had taken two cross-town buses to get in line early for the office's opening at 8am, an hour-plus commute that would have taken ten minutes by car. He had come hoping that somebody could tell him, finally, when he would be allowed to get back to driving. The delay was a bad sign. The clerk returned with a coworker, who handed Rodeo a slip of paper with a phone number. Rodeo had to call the Mandatory Actions Unit, she said, a division of the dmv apparently reachable only by phone.

The driver’s-license debacle had started in June 2017, when Rodeo was nearing the end of a stint at San Quentin State Prison for assault “likely to produce bodily injury”: he’d beaten up a guy whom he believed was casing his house for a robbery. In prison, he’d attended group therapy and took classes that contributed towards earning his high-school diploma, volunteered as a mentor to “at risk” young men and worked at the paint shop, earning $1 an hour.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

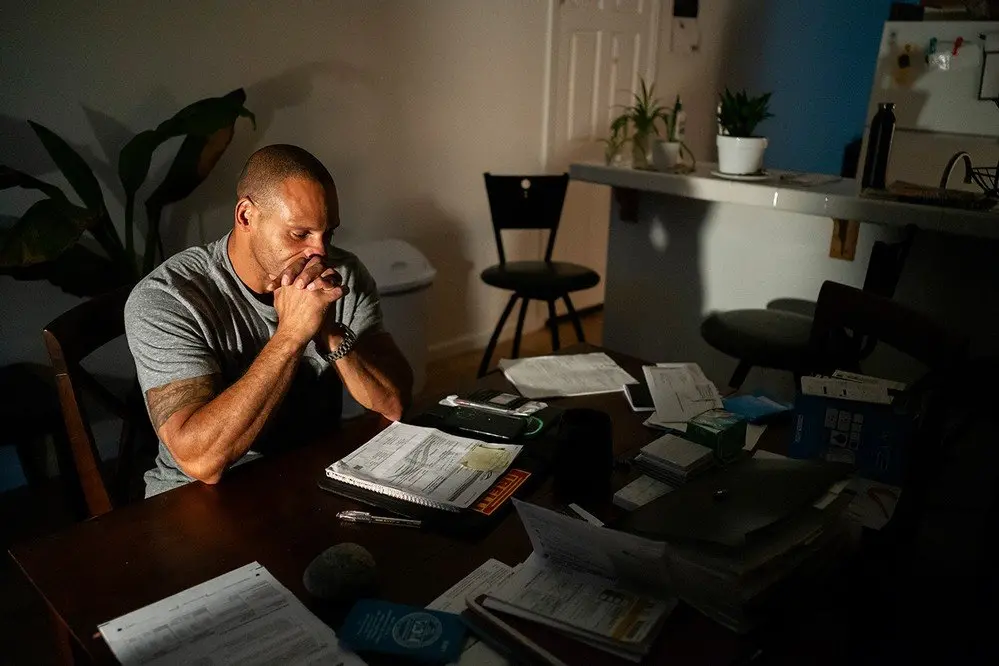

Thanks to “good time” credits, his sentence had been reduced from four years to two, but he hadn’t been able to keep up with child support for his oldest son. (He has one other son and a daughter but said he doesn’t have government-mandated support obligations for them.) The bills arrived each month, addressed to his inmate number and cell unit. His case worker at the state child support agency knew about his situation, but she told him there was nothing she could do. By Rodeo’s last day in prison, on July 30th, 2017, he said he owed $9,787. A few weeks after his release, he learned that his driver’s license had been suspended for failure to pay child support.

A license is one among many basic possessions a person can lose during the course of a long absence from the outside world, a list which also includes childhood photos, underwear, and birth certificates—things that proved you were someone before you became a number in a six-by-nine cell. Rodeo understood that he needed steady work to avoid going back to the hustle, and more importantly, to stay out of the pen, though holding a job could be impossible without a license or a car.

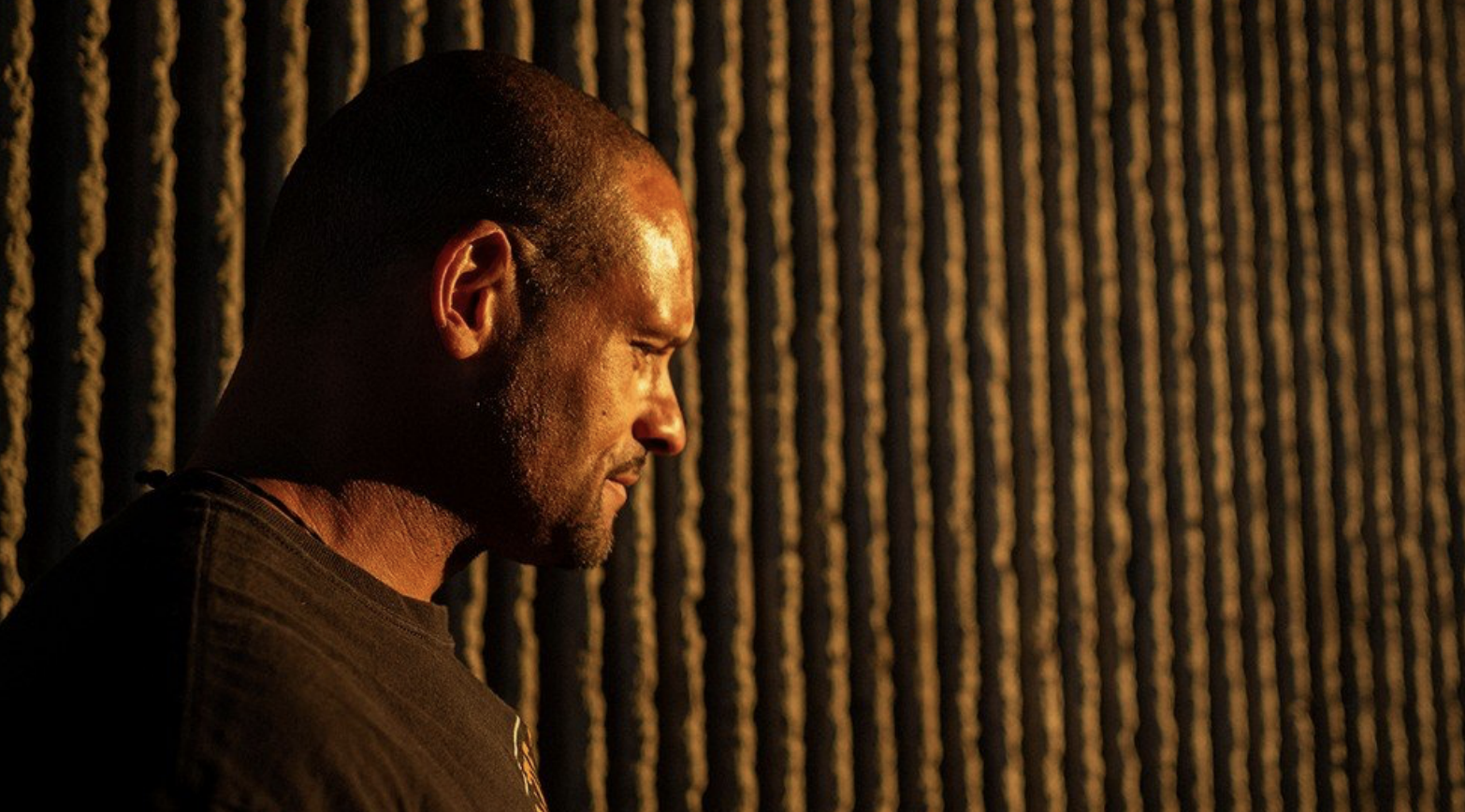

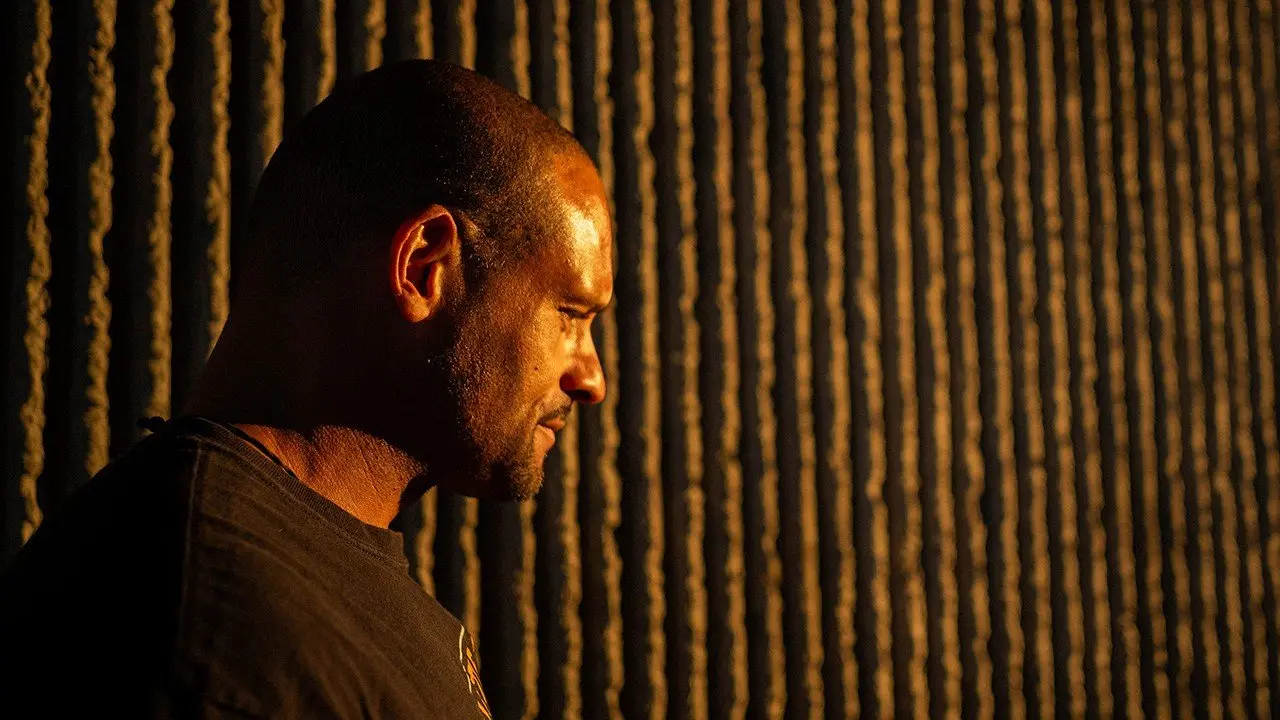

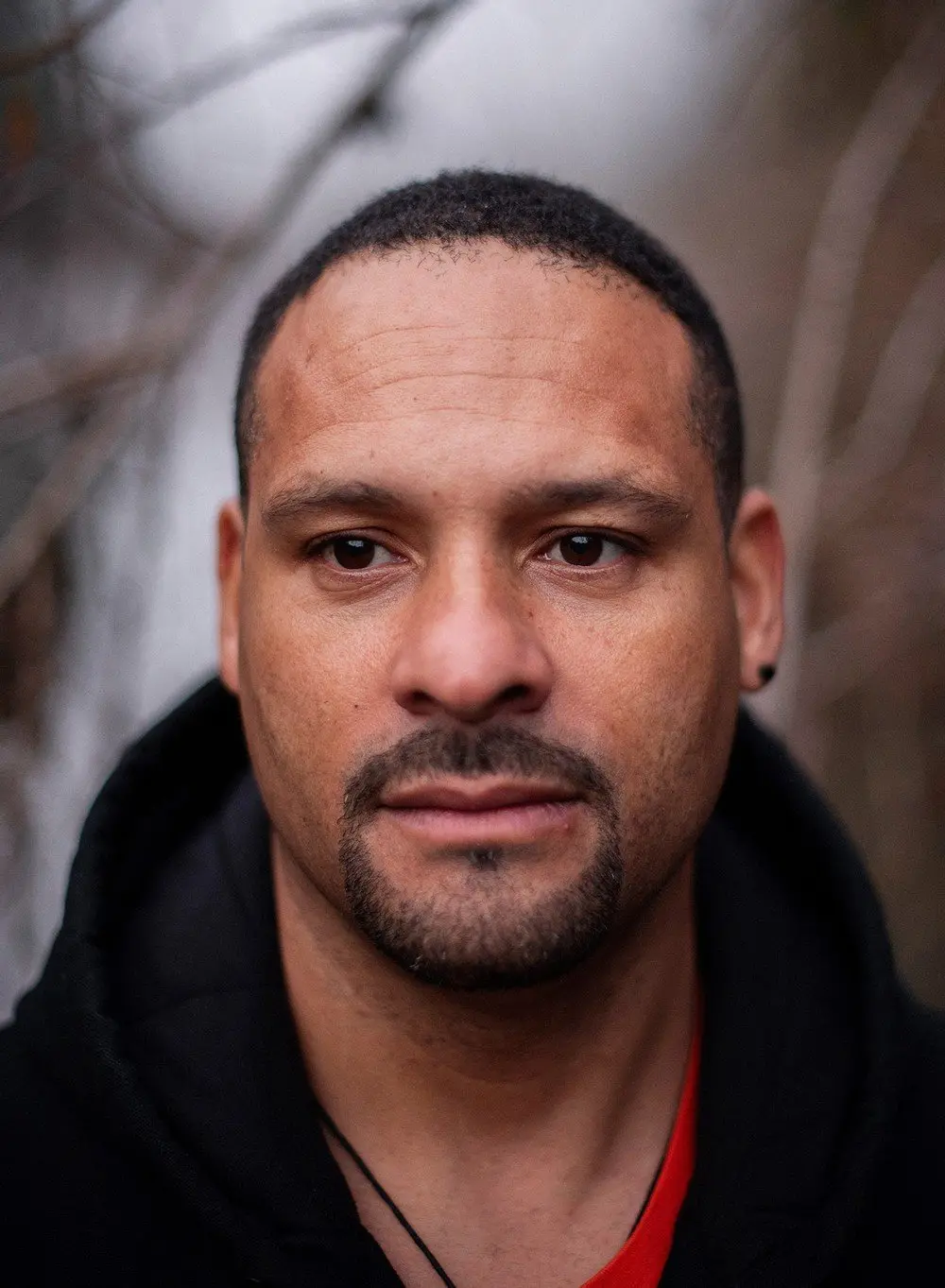

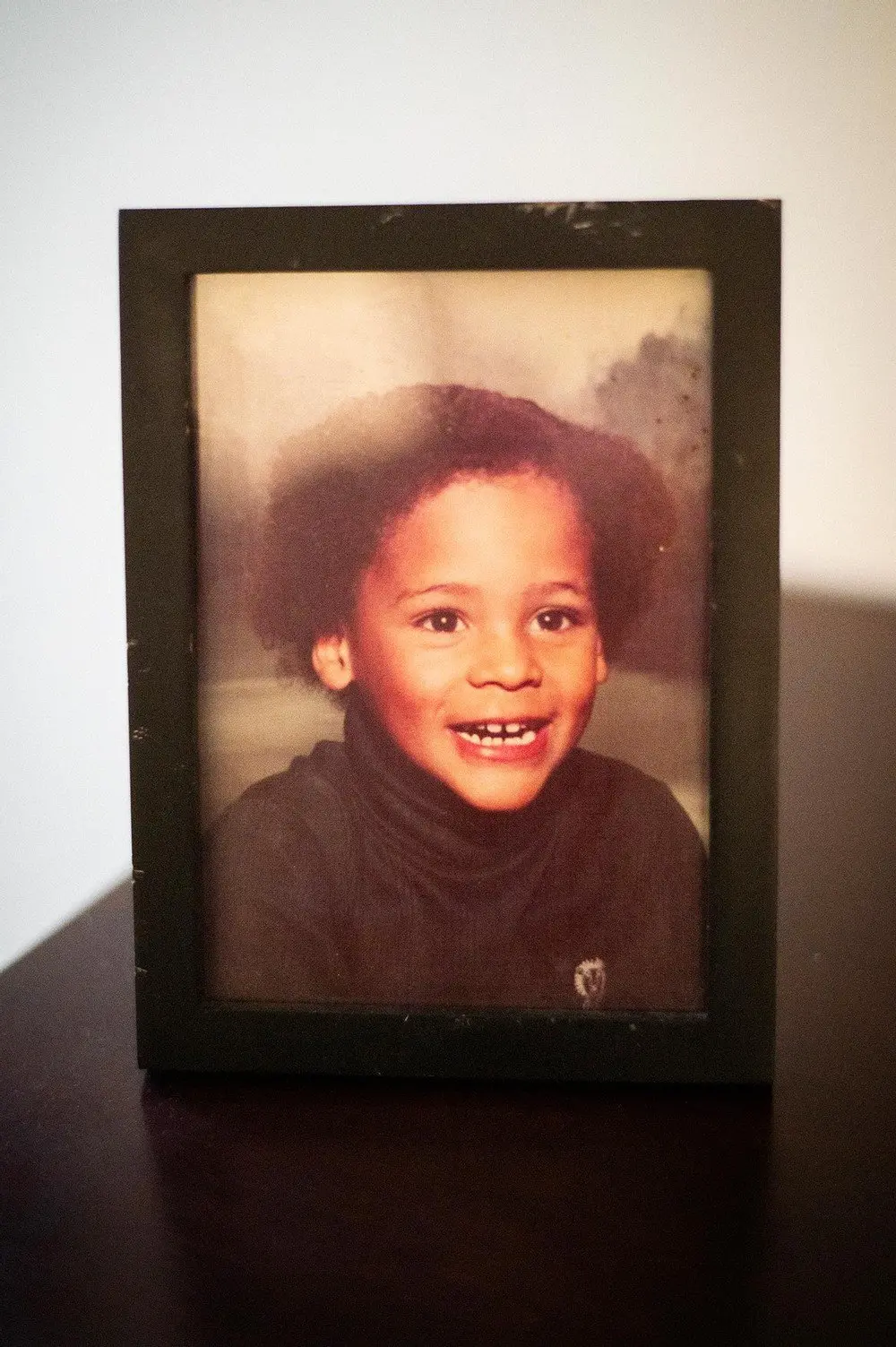

Rodeo preferred to concentrate on what was possible. Even at 42 and fresh out of prison, again, he considered himself an optimist. Tall and broad-chested, he had his mother’s smile, the same gap between his two front teeth, and a trim goatee that cast a shadow of manhood over a babyface. Friends called him a “beast” for the way he threw himself into each day with grim enthusiasm. “It’s sink or swim,” he said. “I’m not the sinking type, you know?”

In an effort to get his license back, he’d called his case worker and left messages. To make regular child-support payments, he needed regular work; to get regular work, he needed his license. That was particularly true for his dream of getting a union job in a construction trade. Union employment comes with higher pay, benefits and regular hours, but workers commonly need both a license and their own vehicle to ensure that they get to work on time—shifts can start as early as 5:30am.

Rodeo had worked since leaving San Quentin. First, he’d used his experience in the prison paint-shop to line up temporary jobs with two decorating companies. Then he strung together construction gigs, when he could. The work paid around $20 an hour, enough to cover his mobile-phone bill and chip in for groceries and rent while staying with his two friends, Jesse and Taryn, in a blue-collar neighbourhood in Santa Rosa. But he struggled to make a dent in the roughly $300 he owed in child support each month. And he couldn’t always hitch a ride to get to a construction site at the break of dawn. If there was anything Rodeo hated more than turning up sweaty and late for work, it was turning up sweaty and late for a date with his six-year-old daughter, the time and place of which often changed at the whim of his ex.

Most of the time his messages to the child-support office went unreturned, but a year and a half after he’d been on the outside, he seemed to catch a break. In January 2019, a new caseworker agreed to release his license for 90 days and told him to head to the DMV. Rodeo had been to the DMV five times since then. Or was it six? On each occasion, a clerk told him there was a problem: outstanding fines; his license was still suspended; his suspended license was expired and had to be renewed. Now it was June, and this time he brought a letter from a judge clearing his fines and a letter from his caseworker granting the temporary stay of the suspension. He had applied for a renewal and paid the fees. He even took a new driving test. If he wasn’t prepared before, he was now.

Rodeo dialled the number on the slip of paper. You have reached the California Department of Motor Vehicles…He paced back and forth by the entrance, as one long-winded automated menu led to another, and another, eventually sending him back to the first one. He hung up. “It’s just going in a vicious circle. It’s literally going nowhere.”

Returning to the front desk, he tried to explain to a receptionist what had happened. The guy shrugged. Rodeo just needed to stay on the line until someone answered. How long would that take? Rodeo asked. An hour to an hour and a half, the receptionist guessed, based on customer complaints. Then, another receptionist—with dyed red streaks and a deadpan stare—stepped in and asked Rodeo for his license number. She scanned her computer screen, scribbled a note, and instructed him to take it to the clerk at window 7. It said that the clerk needed to call the Issuance Unit, not Mandatory Actions. Do not send this customer away.

At window 7, the balding clerk, now incessantly clicking a pen and smacking a piece of gum, took the note from Rodeo and scoffed as he held it up to show his colleague at the next window. The clerk told Rodeo to take a seat. A few minutes later, he called him back up. “So are you going to pay for that one today?” he asked.

“Pay for what?” Rodeo asked.

“The two grand.”

“Two grand? For what?”

“For the fnes.”

“I don’t owe any fines. God, you guys are phhh…driving me crazy.”

The clerk paused and squinted at his computer. “What were you getting done again?”

Those who study and experience life after prison often describe it as an alternate reality. “Did a stretch in prison to be released to a cell,” poet Reginald Dwayne Betts wrote. “Returned to a freedom penned by Orwell.” Others have called it “a parallel universe”, a “purgatory”, a place of “exile”.

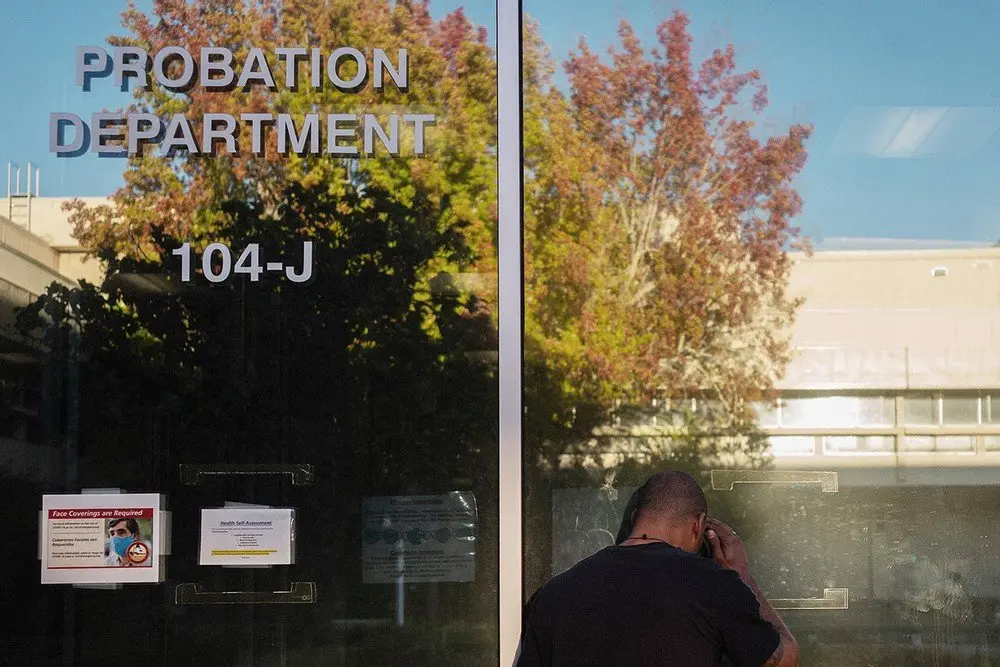

Rodeo found ways to get by in this world. At least four times a week, he rode the bus or walked to the Sonoma County Hall of Justice—a cluster of monotone buildings housing the probation office and day reporting centre, a one-stop shop for the formerly incarcerated offering help finding a place to live, landing a job and getting drug-addiction counselling. The conditions of Rodeo’s release required him to meet two probation officers (POs) there every week, and attend two classes (one for anger management, one for recovering addicts). The day reporting centre was also the place where, if his group was called on the Chemical Testing Line, or if one of his POs deemed it necessary, Rodeo peed in a cup, to test for drugs. “I want to see you doing good out there,” they were always telling him.

Car-less though he was, Rodeo tried to work with what he had. Only so many employers were willing to hire someone with a criminal record and fewer still would tolerate your turning up late or leaving early because you had a class or an appointment with your PO. But he memorised bus routes and timetables, and the shortcuts through the grass that could shave off a few steps. He made mental notes to ask for bus passes (the probation office gave out two per day) and snagged a few extra bags of crackers and trail mix on his way out of the day reporting centre. In a black backpack, he carried a turkey sandwich, granola bars, a jumbo-size bottle of water and chargers for his mobile phone, ankle monitor and breathalyser. The bag, which had a patch sewn on the front, “Making Better Choices”, was a gift from his girlfriend. He used it so much the straps frayed at the seams.

In America, a person under supervision – either as an alternative to prison (probation) or a condition of their release from one (parole) – can face as many as 30 rules that range from vague to “bizarrely specific”, according to a 2017 law review article by a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). These provisions include observing a curfew, refraining from being around guns or anything that looks like a gun, disclosing monthly bank-account statements, avoiding other people with criminal records (including family members), not having more than $100 cash in your wallet, keeping a job, supporting one’s family, getting approval to use knives at work from a parole agent and carrying those knives only while at work or travelling to and from work.

The net effect of these rules is a “nearly impossible burden”, the ACLU lawyer wrote. People have to navigate the narrow strait between “the Scylla of failure to check in and the Charybdis of unemployment”. More pointedly, as civil-rights scholar Michelle Alexander wrote: “Today a criminal freed from prison has scarcely more rights, and arguably less respect, than a freed slave or a black person living ‘free’ in Mississippi at the height of Jim Crow.”

Rodeo has his own analogy: it’s like trying to swim out of a whirlpool in a river. No matter how hard you paddle, the current always pulls you back in. Every now and then, you float by a tree with a branch hanging low and grab it. But the branch always snaps off.

One early morning a few months after his frustrating trip to the DMV, Rodeo woke up in a daze. An old friend from prison named Wolf had invited him to a small house party the night before; Rodeo said they’d drunk shots and a joint was passed around. Now he had a hangover but his jaw and rib cage were also sore. He was sure he’d punched someone but couldn’t remember how the fight started. He remembered yelling at two cops who, after watching him attempt to touch his nose and walk in a straight line, told him he was under the influence and put him in the back of the squad car, where he passed out. As he came to sometime later, the shape of the place grew familiar: the booking room of the Sonoma County jail in downtown Santa Rosa. He heard a sheriff's deputy who knew him call out, “Van Bladel? What are you doing here?” Rodeo had asked himself this question before; he didn’t always know the answer.

He had been in and out of county jail and state prison repeatedly over the past quarter-century. In broad terms, prison is where you’re sent for a substantial time period after being convicted of a crime, and jail is more of a way-station, a place where you’re put after being arrested for an offence and before the courts determine whether to press charges or release you.

These categories are blurred for people on parole. When Rodeo was first involved with the California criminal-justice system, he was sent back to prison if he committed even a minor crime or broke the special rules of his release—infractions that aren’t illegal for other people. In 2011, under a Supreme Court order, California enacted reforms meant to relieve its overcrowded prisons and improve its parole system, which an independent commission had deemed a “$1bn failure”. This new legal regime included what is known as flash incarceration: parolees picked up for smaller things like getting into a bar fight or public drunkenness now spend up to ten days in jail, the idea being that a concentrated dose of punishment will deter them from doing something more serious. Jail has become, in effect, a mini-prison.

Under this evolving system, Rodeo had tallied six stints in prison and 19 in jail. Many of the judges he met talked about jail like it was a second chance, and to some extent he understood that. His jail terms, even if the supposed “flashes” sometimes turned into months, were at least briefer than his prison sentences. But they were so frequent that recently his life felt less like a path to freedom or redemption and more like a maze in which every route he took somehow led back to the same dead end. As a Stanford Law School report disputing the effectiveness of flash incarceration noted, even a few days in jail was disruptive enough to “end employment” or keep people from “important life events”.

On one occasion, Rodeo was jailed for “false identification to specific peace officers”, a misdemeanour. He had been staying with friends who made and sold marijuana oil. “It was a little lucrative,” he told me. One day, the lab exploded and two guys went to the hospital with severe burns. When the cops came and asked for his name, Rodeo lied. They believed him until another officer arrived and recognised him.

This time, after the house party, he was sure he was the one who’d called the cops. It didn’t make sense, though. He didn’t trust the police. Why would he have contacted them? When he got to a phone, he dialled his girlfriend and asked her to Google his symptoms. Has someone drugged him? What were they charging him with?

I visited Rodeo in jail a few days later. He was still trying to piece together how he got there. He hadn’t slept or shaved or worked out, which was how he liked to start his days—lifting weights, listening to music, tuning out the world. Now he felt antsy, like someone was after him, though he couldn’t name anyone specific or didn’t want to.

He thought about asking his PO for permission to move out of the county. Leave it all behind and start over. But when he’d asked before, his PO said it wasn’t possible. He buried his head in one hand, covering his deep brown eyes, which could light up with excitement but when he was down or withdrawn looked like a fire extinguished. “Sometimes you just get so deep into a life you can’t get out,” he said through the glass separating us, pinching back what looked like tears.

The first time Rodeo was put in juvenile detention, he was 11 years old, according to court records, though he insists he was only eight. He’d thrown some rocks at windows with a pack of friends, he told me, and when the cops came, they ran. He thought it’d all be over soon and he’d get to go home to his mother. They lived in a little yellow house near the Russian river, where northern California vineyards and pine groves and farms stretch between rickety towns out to the Pacific. The place drew people in search of escape or a new start.

Rodeo’s mother, Tomi, had come from New York by way of North Carolina. She was an African-American woman and self-proclaimed flower child who fell in love in the time of Woodstock and followed her love westward. One day, after love pushed her down the stairs, she packed up and moved to the river with Rodeo. They didn’t speak of his father much, so most of what Rodeo knew about him came from rumours on the street: gang member, drug addict, violent.

Tomi worked as a bouncer at a local bar and studied martial arts both for fun and self-protection. She was always prodding Rodeo to throw up his little fsts and spar with her in the living room: boxing, muay thai, jiu-jitsu. “Never go through life being scared,” she used to tell him. Some nights, when she worked late, Rodeo slept in a car outside the bar until closing time and then they hitchhiked home. Some days, when she was out drunk or in jail for a misdemeanour like driving under the influence, he would get hungry and climb up on the kitchen counter and eat whatever canned food he could reach in the cupboards.

It’s tempting to think that the circumstances of Rodeo’s life—broken family, single mother, poverty, violence—made his path to prison inevitable, a rite of passage, even. But that would be too simple. Though he often wished his life had been different, easier, there were parts of it that he cherished. Afternoons with Fleetwood Mac and the Grateful Dead flowing from the record player, his mom on the piano. The day his uncle took him on his first hunt, when he shot and skinned a boar and fell in love with the wild. Christmas with mom’s green-bean casserole, a small gift wrapped under a tree he’d chopped down in the woods.

It was only weeks after his first day in juvenile hall that Rodeo began to see himself in the same light as the people deciding his fate. Weeks after he hurt his hands trying to pry open the door of his cell, weeks after a judge declared him a ward of the court, weeks after a counsellor told him, with pity and disdain, that he was the only one who didn’t get what everyone else knew, that he was never going home. Only then did Rodeo start to believe he was a “crazy little s--- who couldn’t be contained”. So wherever the court put him, whether a juvenile detention hall or a group home, he ran.

He ran from Trinity School in Ukiah, from California Youth Homes in San Juan Bautista, from Chrysalis House in Pleasanton, Chrysalis in Livermore, New Life group home in Petaluma. Hitchhiking and panhandling across 50 or 100 or 150 miles, all through his teens, always back towards the yellow house, towards mom, until the cops caught up and dragged him back to court. He knew he shouldn’t run. Still he ran.

By his 18th birthday, Rodeo was breaking into homes and stealing things to sell, like jewellery and guns, and food to eat. Sometimes he and some guys did a loop around the Bay Area, sticking up cheque-cashing joints and 7-Elevens. “When you’re buying a used car off a lot and making a deal for half cash, half weed, half coke or whatever, and you drive away with no driver’s license, no insurance, back to an apartment that you’re technically not paying for yourself,” he said, “you’re basically a ghost. The image of yourself is an outlaw.”

Rodeo went to state prison for the first time after being convicted of burglary and vehicle theft. In 1995, a neighbour caught him and two others stealing a white fur rug and other valuables from a house in Penngrove and loading them into a car they’d stolen. He started his sentence at the N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility (CHAD) and ended it in Corcoran, the prison that also housed Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan. He called his mom every week he could during those first three years behind bars, and every time he could when he ended up in a cell thereafter.

The fight got a hold of him, whether it was guys messing with Rodeo or the other way around. At CHAD, the guards made young inmates fight in an old, gutted bathroom with wrestling mats known as “the gym”. Rodeo earned names like “Valley Boy" and “Country Killer”. He was transferred to Corcoran after he punched a kid who tackled him during a flag-football game.

For a while, Rodeo says he was placed in solitary confinement, and once again the guards staged regular bouts between prisoners. “You get to a point where you’re just numb to everything,” he said. “And then the anger will start to boil from that.”

After a mêlée in the yard, his first cell mate there, Big Sammy, gave Rodeo the name that stuck: Afa, short for a Samoan phrase that loosely translates to “half blood”, or “crazy”. Following a lengthy FBI investigation, in February 1998 a grand jury indicted eight guards at Corcoran for various abuses, including forcing prisoners to fight like gladiators. (They all would later be acquitted at trial.) That same month, Rodeo was released on parole for the first time.

A license is one of many basic possessions a person can lose during the course of a long absence from the outside world. On his first day, the background check came back and his boss sent him home early. They never called him. “You get to a point where you’re like, you’re just numb to everything. And then the anger will start to boil''

At some point Rodeo believed that his mistakes became choices He had recurring nightmares, waking up in a cold sweat and swinging his fists in the air Rodeo the name that stuck: Afa, short for a Samoan phrase that loosely translates to “half blood”, or “crazy”. Following a lengthy FBI investigation, in February 1998 a grand jury indicted eight guards at Corcoran for various abuses, including forcing prisoners to fight like gladiators. (They all would later be acquitted at trial.) That same month, Rodeo was released on parole for the first time.

Rodeo was born in 1976, near the start of a mass-incarceration era in which the United States would imprison people faster than anywhere else in the world. The Nixon administration’s “war on drugs'' spurred the first surge, followed by the spread of tough sentencing laws across the country. The prison population in America doubled between 1975 and 1985, and doubled again by 1992.

When Rodeo left Corcoran in the late 1990s, the number of people on parole in California alone had grown tenfold, from roughly 11,000 in 1980 to 110,000. And thousands of these were violating their parole provisions and returning to prison. The trend alarmed criminologists such as Jonathan Simon at the University of California, Berkeley, who described at the time a “tightening feedback loop” in which “offenders who have not committed especially violent crimes, but who are disreputable” were now caught in the “temporary space between initial release from prison and inevitable return to prison”.

Each time Rodeo was released from prison to parole, he started with the best of intentions. “My mind was like, I’m going to do good, get me a job,” he said. “I would go down and get a couple of applications. But I wouldn’t have any idea really on how to fill s--- out. I didn’t know my Social Security number. I didn’t have a Social Security card. For me to fill out an application, it was a process. Go down to the county-hall office. Get money. All these initial steps, right?” Most of the applications he did file went unanswered.

Once, he said, a plumbing company interviewed him after he checked “no” to the question, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” When the manager asked about the gap in his work history, Rodeo lied and said he’d taken time off to care for a sick family member. He got the offer. But on his first day, the background check came back and his boss sent him home early, saying they’d call him after sorting it out. They never did.

At one point, after he worked on an inmate-fire-fighting crew, Rodeo said the captain of his team agreed to write a letter of recommendation for the Santa Rosa Fire Department. But the plan was scotched because an Emergency Medical Technician license is a prerequisite for firefighters, and most former felons are legally barred from getting them. Former inmates are blocked from many different kinds of employment due to such licensing restrictions and background-check requirements, which multiplied with the country’s tough-on crime policies.

So Rodeo took odd jobs, often the kind that wore down his body and made his fingertips throb. Construction was his mainstay. Running steel pipes, hooking hoses, pumping and pouring concrete. He worked as a bouncer at night clubs, Quincy’s, Hopmonk. He fixed tyres and brakes at Big O Tires. He washed dishes. One year he worked as a prep cook at a golf club, because the owner knew his mom. He worked winters on crab-fishing boats. He made between $8.25 and $20 an hour, depending on the employer. But the jobs rarely lasted, and in between, the lure of the hustle was hard to ignore. “There’s somebody in me who goes, Well s---, I can make a phone call right now and say I need a brick,” he said, referring to cocaine to sell. “And then I can make seven more phone calls, and by five o’clock tonight, I could have five grand in my pocket. I have a good six months ahead of me where I could do that and stack my frogs before police are like, ‘What are you doing?’” Rodeo figured he’d quit dealing before the cops caught on, but it rarely panned out that way. “The money comes so fast. Everything starts coming so fast.”

Looking back now, he could see how his good intentions morphed into mistakes. Like the time in 1998, fve months after Corcoran, when he went to a shooting range and the cashier called the police after overhearing Rodeo mention doing time. The cop waited and watched him shoot a .45, then arrested him for firearm possession, a felony for someone with a prior offense. “The defendant did not believe that going to a ‘controlled environment’ to fire a weapon would get him into trouble,” a probation report stated. “He would like the Court to consider that he is very young and has a lot of community support. The defendant hopes not to serve a long prison sentence and realises he made a bad decision.” He got two years in state prison for that one.

Or the time in 2000, when a probation officer turned up to his house unannounced to find a new car and a motorcycle in his driveway, Rodeo said, “and like $7,000” worth of exotic pets inside—“birds, two snakes and a big iguana”. In prison he’d read a book about reptiles and “damn, that s--- intrigued me”, so much that he later took a junior-college herpetology class. Owning exotic pets was also a “status thing” for him, he said. The PO questioned him about how he afforded his lifestyle—it’s a parole violation to be unable to show where your money is coming from – though she ultimately had him arrested for not having proof of car insurance, what’s known as “failure to prove financial responsibility”. The court eventually dismissed the charge, but not before he’d sat in jail for three months.

Or in 2002, when he was arrested for assault, and after much deliberation, a judge showed some leniency. Instead of sending Rodeo to prison he ordered him to live at a group home and report to probation. “Mr. Van Bladel, you continue to present quite honestly a conundrum for the Court,” the judge had said. “You’re very well spoken. You’re obviously in very good health and good physical condition. You were described by your parole officer as a schemer and a manipulator… I really don’t know…Somewhere, somehow, I really believe that you have the talent and you have the ability and that you’re not some sort of evil person…the kind of young man that eventually might turn around other young men.” Rodeo later absconded from the group home. After he was caught, his probation was revoked and he ended up serving a year in state prison, anyway. He missed the birth of his first son, and the toddler years of all of his children. At some point, Rodeo believed his mistakes became choices.

In 2001, as the number of people incarcerated in America continued to climb, the Department of Health and Human Services published a series of papers on the journey from prison to home. More and more inmates were being subjected to punitive isolation and “unprecedented levels of social deprivation for unprecedented lengths of time”, psychologist Craig Haney wrote in one. The psychological pressures of confnement could “uniquely disable prisoners for free-world integration”, he went on, and the consequences included an impaired sense of identity, irritability, aggression, anxiety and panic attacks, hopelessness, chronic depression, hallucinations and suicidal ideation.

Rodeo told me about how, a few years ago, he started noticing a strange light in the sky. The first time, he was outside smoking a blunt with his then-wife and a friend. It’s a UFO! they’d joked. Then the light grew and grew until, Rodeo said, it was hovering above their heads. “I remember the feeling I had…I didn’t speak on it,” Rodeo told me. Another time, he mistook the light for the North Star. “I’ve been in a lot of situations, especially in prison, life-threatening situations. This was a completely different feeling of…no say. Just complete helplessness.

The unsettling sensation overtook him yet again as he lay in bed one evening watching a show about paranormal phenomenon. Somebody’s in here with me, he thought. I’m not alone. He walked around the house, into Jesse’s and Taryn’s bedroom, but seeing no one, he tried to calm himself. Dude, you’re trippin’. Just chill out.

Rodeo relayed these experiences to me as we sat at the back of a city bus. He always sat in the back of the bus, for the same reason he preferred to shop along the outer perimeter of the grocery store, his back against the wall. Life is short, the adults often reminded him when he was growing up, and for a while he firmly believed he wouldn’t live past 20. Many of his friends were either still in prison or out and battling addiction. Some had been stabbed or shot to death or died from an overdose.

Still to be alive in his 40s felt miraculous, and he saw no choice now but to appreciate each passing moment. At San Quentin, in the group-therapy and reentry support programme called Insight Garden, he talked about his life experiences with other inmates and volunteers. “I would walk through the outside garden on H-unit’s yard and a butterfly would fly by, or a lizard, and I’d have this moment of clarity, like, Life. It is important.” He thought about his daughter and sons. “It was just a f---ing light switch: I had a lot of violence in my life, crazy, chaos and evil. I realised that I was basically setting the same pattern for her and my boys.”

After San Quentin, Rodeo started dating someone new, an old friend who’d written to him when he was in prison. Alyxis, whom he calls Alley, was a pescatarian who taught Pilates and worked at a travel agency in the evening while studying to become a dental hygienist. Rodeo admired the way she pursued her goals, how she kept him in line and dared him to try new things, like enoki mushrooms and running endurance races together and balancing a chequebook. Once a week, he visited his mother by the river, with a bunch of flowers and snacks in hand, and they spent the afternoon catching up on the years gone by. He called his sons. He met his daughter for a date at the park, or movies at home.

There was no more going back, he told himself. Even when the work dried up and he stared at the single dollar bill left in his wallet. Even when he came home from a day of job rejections and cried on the toilet. He felt lighter knowing he was doing his best to live right. He ran into sheriff’s deputies on the street, who instead of arresting him, shook his hand and asked how he was doing. One even invited him to join their softball team.

But it was hard to bounce back from small setbacks, to write an email, sit at a job interview or stand in line at McDonald’s — to be normal. He had recurring nightmares, waking up in a cold sweat and swinging his fists in the air. “It f---s up your nervous system. You know what I mean?”

During Rodeo’s two and a half months in jail after the marijuana-oil fire, Alley got a call from the hospital. A neighbour had found Tomi unconscious in her apartment and called an ambulance. She had been diagnosed with liver cancer, but never told Rodeo. The cancer had advanced. Tomi asked to see Rodeo one last time. Rodeo got a hearing to ask permission to visit his mother, but he said the DA's office opposed his request. “I threw money at the courts,” he recalled, “like, ‘I will pay two or three officers their day’s salary if you can get them to chaperone me.’ They had the spokesman for the Sonoma County Sheriff's Office stand up in court and say, ‘We won’t accept anything he has to offer, his drug money, his ill gotten gains, anything that he says and posits.’ They just tried to make me sound so horrible. I was like, ‘Well, first of all, it’s literally not my money. It’s my girlfriend’s. She’s a righteous person.’ They were like, ‘We don’t want it. Nobody’s going to take him.’ ”

The judge adjourned the hearing before making a decision, Rodeo said, and he returned to his cell believing his request had been denied. But later the sheriff came by with the key. The judge had decided to let him go. Two deputies escorted Rodeo to the hospital. “I went home trying to work up the courage to tell Moma Tomi that court did not go well,” Alley wrote on Facebook that day. “To my surprise I got a phone call from Moma T crying with pure joy telling me that her boo boo baby boy was standing in her room.” A blue scarf held back his mother’s long wavy hair. Rodeo, in grey jumpers stamped by the Main Adult Detention Facility, leaned into her bony arms and buried his face in her neck. A few days later, she died.

The father of American parole, Zebulon Brockway, wrote that his career as a prison warden began after losing at poker. Growing up near the New England coast in the mid-19th century, Brockway described himself in his autobiography as an unruly teenager drawn to “feasts and frolicking”. He was expelled from school for “open insubordination” and truancy. In the poker game, Brockway lost all his own money plus $40 that he’d borrowed, but he got lucky. The victor returned his winnings. “That evening’s experience ended forever for me all participation in games of chance,” he wrote.

Later, as a prison superintendent at the Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York, Brockway honed what he advertised as a more humane approach to punishment in America. Through a combination of education, religion, military discipline and medical treatment, Brockway said that he could build “Christian gentlemen” and “protect the public from future transgressions”, according to criminologist Alexander Pisciotta’s book, ”Benevolent Repression: Social Control and the American Reformatory-Prison Movement”.

Brockway and his Elmira colleagues decided which inmates were eligible for the country’s first parole programme using factors such as criminal history, work record and attitude. Parolees had to follow three general rules: stay with an employer for six months; submit a monthly report; and conduct themselves with “honesty, sobriety and decency, avoiding low or evil associations and [abstaining] from intoxicating drinks”. Brockway gave tours at his “college on the hill”, explaining how he helped his charges become “law-abiding citizens”. He was hailed as a “prophet” who’d discovered the “final reform panacea” for “the American crisis in crime and criminal justice”.

A decade later, the New York State Board of Charities revealed that Brockway had subjected his inmates to foggings, solitary confinement and psychological torture. Elmira wardens were found to have made arbitrary decisions about who was granted parole and when to revoke it. They considered black people to be “biologically, psychologically and morally inferior”, Pisciotta reported, “and, as a result, less salvageable than their white counterparts”.

Brockway’s concept of parole (and his reputation) not only survived the scandal, it "launched the American criminal-justice system on a false path to reform," Pisciotta concluded. Parole has since withstood many more rounds of controversy and criticism, justified and not. “Whenever fears of a ‘crime wave’ swept through the country, or whenever a particularly senseless or tragic crime occurred,” historian David Rothman wrote, it was blamed on a system too eager to let “bad” people out on parole.

By the 1980s, criminal-justice officials were debating whether parole should continue at all. It had “drifted along without a positive vision of what control was and how to achieve it,” in the words of Simon, the professor from the University of California, Berkeley. Instead, with American prisons overflowing, parole expanded its reach. California and other states adopted drug testing, risk prediction models and computer databases of offender records to help automate decisions that had previously been left to the discretion of parole boards and officers. The irony, according to Simon, was that what began as a system to help inmates ultimately return to their communities as productive citizens, now functioned as an extension of incarceration for people “defined as inherently, irredeemably dangerous”.

Today, 4.5m Americans are living under parole or probation supervision, more than twice the number of people in prison. According to Human Rights Watch, in 2017 more than half of state-prison admissions in 20 states resulted from parole violations, often for public-order offences “like disorderly conduct or resisting arrest, misdemeanour assaultive conduct, shoplifting and drug offences”. These figures don’t count people who are put in jail for rule violations.

One hot afternoon, a month after his visit to the DMV, Rodeo emerged from a small wood-panelled building overlooking the freeway, wearing a necklace with two pendants, one made of African jade that belonged to his mother, the other made of black onyx containing her ashes. “So she’s with me everywhere I go,” he said. He had just met a counsellor at the day-reporting centre and been given a drug test.

When his jail stay for lying about his identity was over, Rodeo asked his parole officers for permission to move into a halfway house, hoping it might help him tackle his alcohol addiction. He’d always considered himself a social drinker, the kind who was fun to be around. But he had started to see how the drinks added up. One beer after work to lighten the load led to a few more rounds at a bar, and then, when his nightmares persisted, he drank to fall asleep. He asked Alley if she thought he drank a lot, and “she was like, ‘Baby, you drink more than anybody I know’.”

After six months in two different halfway homes, he thought he was ready to move back in with Jesse and Taryn. His PO agreed, but tacked on some new conditions, which is how Rodeo ended up with the breathalyser, ankle monitor and a weekly addiction class. Rodeo tried to be open to these classes. They usually started out being boring, because no man fresh out of prison wants to talk about his feelings, but they did get interesting when the role-playing started, when you’d see a dude who did ten years in the pen look into the eyes of a dude with a face-tattoo named Brutus and say, “Hey Suzie, you’re a great girl. I appreciate you.” After a while, he had to admit that the classes helped him understand why he was “f----d up”.

There were days when Rodeo almost appreciated being on parole—the way the rules gave him structure. He even found his PO, the one who was known as a hard a-- and threw guys in the slammer whenever he felt like it, to be fair, if strict. The officer had recently promised him that if he “did good” he’d push for Rodeo to be released from supervision before his three years were up.

The sheer burden of it all could still get to him, though. As we left the day reporting centre for the probation office across the street, one of the straps on his backpack tore off. He tied a knot, swung it over his shoulder, and kept going. “My ultimate thought at the end of it all is if I fail, it’s because I allowed myself to fail,” he said. “But if I fail at every process these people want me to do, then I will go back to hustling. I will not, ultimately, fail fail. You will never see me on the streets homeless, f----n’ hungry.”

At the probation office, Rodeo’s PO was out, so he filled out a “half sheet”, a note confirming he’d come by as required and listing his plans for the day. We moved on to the welfare office to ask when he could renew his food stamps, then walked to the bus stop to head home. Four hours into the day we were both sweating.

As we waited for the bus Rodeo munched on trail mix and talked through the upcoming week. He wanted to get out of mixing concrete, both to find something steadier and because his boss, Darron, hadn’t given him a raise. Still, he felt loyal to the guy for giving him a chance when no one else would. Recently, Bobby, a friend in a local painter’s union, offered to help him get a job in his company. All Rodeo had to do, Bobby said, was go to the union hall, pay a $100 fee and swear in.

As it turned out, Bobby was wrong. The sign-up fee was closer to $500, not $100. Alley had offered to lend him the money. “I know you’re good for it, keep doing what you’re doing,” she always told him. But she’d already spent thousands of dollars to pay for his phone, dinners out together and his mother’s funeral costs. He decided to stick with construction a bit longer. By this time Rodeo had got his license back, so he also planned to get a second job driving for Sam’s Taxis. He hadn’t forgotten the shortcuts that drew big tips from customers in a hurry.

He still needed a car. Darron offered to sell him a beat-up Honda for less than $1,000 and cover the repairs it needed in exchange for a week’s work without pay. Rodeo said he had texted Darron several times since, but Darron replied that he was busy and would call back later.

A city bus pulled up to the stop. Rodeo hopped on, but as he opened his wallet he realised he only had county bus passes left. He’d forgotten to ask for more city passes at probation. He asked the driver when the next county bus would arrive. The driver didn’t know. We deliberated whether to wait, or walk 40 minutes in the heat. An old man pushing a bicycle passed by. “It’s usually every hour,” he said. “Somewhere between an hour, an hour and a half.” We decided to walk. As we left the bus stop, the other strap on Rodeo’s bag ripped off. “Oh, look at that. This is one of those days!” he said, slinging the first strap he tied earlier across his back, as we marched on.

I saw Rodeo a few more times that year, in late autumn. The taxi gig hadn’t worked out; he’d done a one-day trial but the dispatcher didn’t summon him for a single ride. Since the car cost $100 a day to rent, Rodeo didn’t think it was worth the risk. He was in high spirits, though. He was working, building a concrete wall around someone’s garden, and thinking about what Christmas presents to buy his daughter and Alley, as well as how to spend his 43rd birthday on December 10th. After his mother died, he’d received an inheritance passed down from his grandfather, a pastor and butcher from North Carolina whom Rodeo had met when he was little.

A month later, however, in January 2020, Rodeo was arrested for public drunkenness and jailed for almost two months. He withdrew. I made plans to visit him, but then Alley messaged me saying that he’d asked me not to come. He got out in early March only to find much of the world shutting down because of the covid-19 pandemic.

It felt like a cruel joke to go from jail to quarantining at home, but there were unexpected upsides. The probation office, like many government buildings, had closed for the time being, which meant Rodeo no longer had to report to his officer in person or submit drug tests as frequently, though he still checked in by phone. He joined up with a friend working on renovations for a handful of wealthy clients looking to build extensions to their houses. But when wildfire season came and the skies filled with smoke, the projects fizzled and Rodeo went back to picking up temporary jobs. He made it through the rest of the year without being sent back to jail. In November 2020, his county-supervision term ended. Alley treated him to dinner at a steak-and-crab house to celebrate.

By the time I saw Rodeo again, in September 2021, he’d been off probation for almost a year. He had moved out of Jesse’s and Taryn’s and into his own place, a modest two-bedroom with a garage where he kept his weights and his mom’s old piano. He filled his kitchen and bedroom with house plants and decorated the other bedroom with stuffed animals in case his daughter slept over. He hadn’t seen her in several months, after a disagreement with her mother, and was contemplating renting out the room. There were rose and blackberry bushes in the backyard. Both had shrivelled in the summer heat.

On the morning I visited, we chatted while listening to his phone play hold music. Rodeo was in the middle of making another round of calls: he needed to renew his health coverage, dispute an insurance bill for a motorcycle he no longer rode and reissue a money order for his rent, which his landlord told him had been taken by a family member with an addiction. After his latest gig with a tree-service company had ended, Rodeo was job hunting again. He had just applied to a shed-building firm, where his friend Shane worked as a production manager, and which offered vacation days, a pension plan and bonuses for employees who hit assembly-line quotas.

We set out in a used truck he’d bought with the inheritance money. (The deal with his boss, Darron, had fallen through.) Taryn had recently been injured in a car accident and needed a lift to a doctor’s appointment. Rodeo had agreed to drive her there and help with a few errands if she’d pay for petrol. On the way, his phone rang. It was Shane. Rodeo had been approved for an interview, for the next day at noon.