It was late on a Monday afternoon and the reporter on the phone was asking about sick passengers and a plane being quarantined at Milwaukee’s General Mitchell International Airport.

“Are you sure they said ‘quarantined’?” asked a stunned Paul Biedrzycki, the city’s director of disease control and environmental health.

Quarantining an entire plane would be a huge deal.

The last time the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a quarantine order was in 1963 for a woman thought to have been exposed to smallpox. The agency had never quarantined an entire plane. Such an action ran the risk of alarming passengers and the public on what was likely to be a busy travel day.

It was Feb. 7, 2011, the day after the Green Bay Packers had won Super Bowl XLV.

A quarantine order goes beyond separating people with a contagious disease from those who are disease-free; it means restricting the movements of anyone who has been exposed to the disease. By presidential order, the measure is only authorized for a dozen or so diseases including yellow fever, cholera, plague, smallpox and Ebola. If the word “quarantine” didn’t scare people, the list of diseases surely would.

The incident that day began when a pilot on Southwest Flight 703 from Tampa called in a public health emergency to the tower in Milwaukee. Three of the 115 passengers on board were sick with flu-like symptoms — fever, cough, difficulty breathing. All three had been put on oxygen. By the time the plane landed, a dozen passengers were said to be sick.

Airport officials soon learned something interesting about Flight 703 that could point to the presence of a communicable disease. The plane included at least 12 people who had returned from Cozumel, Mexico, on a cruise in which many of the passengers had fallen ill with flu-like symptoms.

The jet was ordered to the airport’s international terminal. Everyone remained on board; some passengers began posting comments about the situation on Twitter and Facebook.

When emergency medical technicians went through the plane, they found only two passengers asking for a medical evaluation; both had chronic underlying illnesses, such as respiratory infections, that could have caused their symptoms.

While airport spokeswoman Pat Rowe called the 2011 incident an “appropriate response,” given the report of 12 passengers sick, Biedrzycki reached a very different conclusion.

In his view, there had been a number of serious mistakes. Officials should never have been frightening people with the word “quarantine.” The local health department should have been alerted of a possible emergency right away; it never was.

Finally, and most importantly, the health department was never able to conduct a full investigation into the possible presence of a communicable disease — a process that would have involved delving into the flight manifest, interviewing the sick and determining whether any of the healthy may have been exposed to a disease.

“This was a big screw-up, and caused a lot of panic and alarm,” Biedrzycki said.

The incident revealed gaps in America’s emergency planning for communicable diseases aboard planes — gaps that were still present four years later when the U.S. Government Accountability Office investigated.

“The United States lacks a comprehensive national aviation-preparedness plan aimed at preventing and containing the spread of diseases through air travel,” the GAO found.

Almost two years later, there is still no plan.

How connected is the world?

While many individual airports have plans of their own, these are designed to deal with a communicable disease on only one or two inbound planes, not a full-blown epidemic that could involve dozens of planes flying to airports across the U.S., according to the Federal Aviation Administration.

Countries are required to have a national aviation preparedness plan for communicable diseases under a 2007 addition to the Chicago Convention, an international aviation treaty signed by the U.S. and other nations.

Both the U.S. Department of Transportation and CDC agreed such a plan could have value. But both felt another agency, not their own, should lead the effort.

In response to questions, CDC issued a statement saying, “Relevant agencies have met around the concept of developing a National aviation communicable disease response plan.”

Jonathan D. Quick, a faculty member at Harvard University and author of the forthcoming book, “The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It,” said a national plan should be put in place.

“Unfortunately,” he added, “the history of diseases is that things that should be done aren’t done until there’s an outbreak.”

The link between global travel and the spread of disease did not start with the airplane.

“The first major global health threat in which modern transportation played a large role was the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918,” according to a report earlier this year by the National Academy of Sciences. “In that pandemic, travel by steamship and rail, not air, accelerated the spread of disease.”

A series of outbreaks over the last 15 years, however, have hammered home the link between air travel and communicable diseases: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, swine flu in 2009 and Ebola in 2014, among others.

“If you’re in aviation, you’re in the infection control business. The volume of air travel is just so vast,” said Mark A. Gendreau, chief medical officer of Beverly and Addison Gilbert Hospitals in Massachusetts, and one of the first to study the spread of infectious disease on aircrafts.

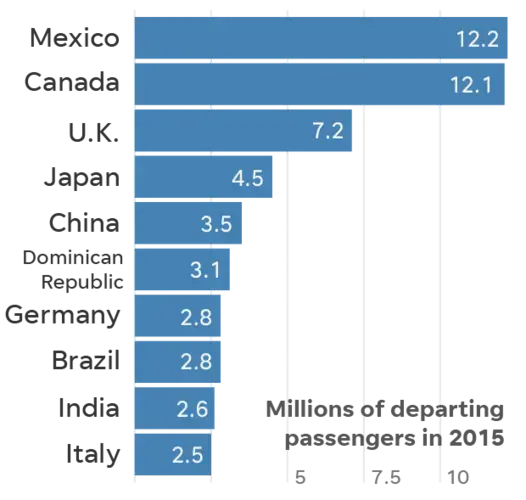

Yet at a time when airlines serving the U.S. carried a record 932 million passengers, and the global total reached almost 3.7 billion, the GAO’s report found numerous examples of poor coordination on communicable diseases.

CDC officials complained that the information on sick passengers they receive from airlines and the control tower is often incomplete or inaccurate.

Airport staff cited similar problems. In one case, an airport launched an Ebola response after an airline told them of a suspected case. The airport discovered later that the passenger was traveling from East Africa — not the Ebola-affected region of West Africa. Moreover, the passenger was not suffering from any physical illness at all, but from fear of flying.

Cleaning crews said cabin staff sometimes fail to inform them when a plane has been contaminated by blood, vomit, feces, saliva and other potentially infectious bodily fluids. But airline workers also complained about the cleaners; one said, “cabin cleaners sometimes use the same towels to clean potentially infectious materials and later to clean food service equipment such as coffeemakers.”

Airports officials said that agencies responding to sick passengers sometimes end up working cross-purposes. In another suspected Ebola case, one group of responders blocked off a road at the airport to give themselves room to dress in protective equipment. Inadvertently, they blocked all the baggage-handling trucks, which in turn blocked other responders who were arriving at the scene.

Finally, Department of Transportation officials have complained that the CDC sometimes issues guidance to airlines without running it past DOT, leading to potential safety problems. For example, if the disinfectant used to clean suspected Ebola contamination is not compatible with the aluminum and other materials on the plane, “the aircraft could be damaged, which could negatively affect its airworthiness,” GAO noted.

The lack of uniformity in dealing with communicable diseases during air travel was evident when the National Academy of Sciences asked 50 different airports in the U.S. and Canada how they expect to learn of an incident aboard a plane. They found 15 different notification procedures.

One airport explained: “It’s hoped that a flight crew’s discussion with an inflight medical consultant (such as Medlink) would give us advance notice; however, I’m afraid we may not learn of the issue until first responders have already made contact with the ill passenger.”

The National Academy also examined one issue raised by the 2011 incident in Milwaukee. Researchers asked airports whether their plans took into account the possibility of social media posts by passengers about disease on an inbound flight. About 39% said yes, 37% said no. Most of the remaining airports said they didn’t know.

To learn more about how airlines deal with infectious diseases, The Journal Sentinel prepared an online survey, which the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA offered to members; 106 responded, an unscientific sampling from a membership of 50,000.

The responses, however, offered a first-hand glimpse into an area that garners little attention: the health conditions aboard airplanes.

About 82% of those responding said their airline needs to improve its communicable disease policy. About 70% reported that they somewhat-to-strongly disagreed with the statement: Crews responsible for cleaning airplanes after sick passengers do a good job.

In more detailed comments, attendants described cases in which cleaning crews demonstrated little knowledge of how to clean biohazards such as vomit or feces, and wiped galley countertops with the same cloths used to clean the bathroom floor.

“If it’s happening the way they describe, that’s a real concern,” said Quick, the Harvard faculty member.

United flight attendant Diane Johnson described an incident in the spring of 2016 in which a passenger vomited violently over several rows inside an aircraft. When the cleanup staff arrived after the plane had landed, they were not carrying special biohazard kits. They simply wiped down the floor and seats. One used sparkling water as a cleaner.

“Their supervisor said they were not trained,” in the cleanup of biohazardous materials, Johnson said. “He was very honest.”

Sara Nelson, the union president and a flight attendant herself for 20 years, watched how the airlines handled the 2003 outbreak of SARS and said the companies appeared to have learned little when the Ebola outbreak occurred in 2014.

“Nothing had really changed,” Nelson said. “And I would argue the airlines were less prepared.

“We don’t do enough through government, through the infrastructure of the industry to learn from the experiences of the past. That became very clear during the Ebola crisis.”

As one example, she said during the Ebola outbreak, “the union had to fight to wear gloves on board.” At first, flight attendants asked to wear both gloves and masks, and were told by the airlines that they could not. Then some airlines struck what they viewed as a compromise, Nelson said. Flight attendants could wear gloves, but only in economy class, not first class.

Nelson said several airlines followed the “compromise policy” for a short time until flight attendants informed a federal health official and received permission to wear gloves throughout the plane.

Health experts, however, remain dubious about whether gloves, and even masks, would be of much help to flight attendants with a sick passenger.

“If you are with somebody who is symptomatic with Ebola, you need a lot more protection than that,” Quick said.

When The Journal Sentinel asked about the problems cited by the flight attendants, the trade association Airlines for America sent this statement:

“Airlines work continuously to keep their aircraft clean for their passengers and crewmembers. In addition, (the association) works closely with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and other government agencies such as U.S. Customs and Border Protection, when there is a communicable disease threat to ensure that our member airlines are kept informed regarding any specific government guidelines during the outbreak.”

The spread of disease isn’t confined to international flights, although they have drawn most of the attention in recent years. Most inbound flights to the U.S. have domestic connections, meaning that passengers can land, proceed through customs and board connecting flights before they show any symptoms, before anyone realizes they have a communicable disease.

In fact, diseases not only fly on planes to new countries, then on to different regions of those countries, but in some cases, illnesses spread mid-flight, passenger to passenger. Although the risk of in-flight transmission is considered low, medical literature includes probable in-flight transmissions of SARS, swine flu, measles, mumps and norovirus.

And the risk doesn’t end when a passenger steps off the plane.

“Malaria cases occurring in and around airports all over the world in people who have not traveled to endemic areas, known as airport malaria, are evidence that malaria-carrying mosquitoes can be imported on aircraft,” wrote Gendreau and colleagues in a 2015 paper in the journal Microbiology Spectrum.

Such experiences underscore a major challenge facing scientists and travelers: There is much we’re still learning about how diseases spread.

Conventional wisdom, repeated in numerous scientific and medical journals, has long held that one passenger is highly unlikely to catch a disease from another unless they are seated within two rows of one another for a flight of at least eight hours.

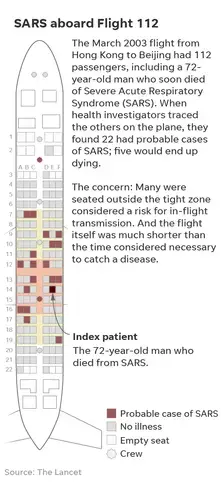

That precept failed on Air China Flight 112 from Hong Kong to Beijing in March of 2003.

One of the 112 passengers on the flight was a 72-year-old man who’d developed a fever four days before the flight. In the days leading up to the flight, the man had been visiting his brother in a hospital ward that held SARS patients.

Upon arrival in Beijing, the 72-year-old was hospitalized. He died five days later of SARS.

At least eight days after the flight, health investigators began contacting other passengers. They reached 65; of those, 18 had come down with probable cases of SARS. Chinese health authorities identified another four passengers and crew from the flight who also came down with SARS. All told, five of those 22 SARS patients from Flight 112 would end up dying.

Not only had the flight been less than half of the eight hours thought to be needed to transmit a disease, nine of those who became ill were seated more than two rows away from the 72-year-old man; two had sat seven rows in front of him. Flight 112 is now considered to be “a superspreading event,” triggered by a person able to transmit disease to a large number of others.

Claude Thibeault, medical advisor to the International Air Transport Association, a trade association, said what happened aboard Flight 112 has been misinterpreted.

“People automatically assume there was transmission,” said Thibeault, whose background is in aviation medicine. “We cannot prove there was transmission on this plane. They could have already been infected when they got on board.”

In a separate study, researchers looked at Flight 112 and 39 other flights that had carried SARS-infected patients. Five of the 40 flights were linked to probable cases of in-flight transmission.

“As the first severe contagious disease of the 21st century,” Gendreau and a colleague wrote in the journal The Lancet, “SARS exemplifies the ever-present threat of new infectious diseases and the real potential for rapid spread made possible by the volume and speed of air travel.”

They wrote, too, that the unusual distribution of passengers who became ill after Flight 112 “emphasizes the need to study airborne transmission patterns aboard commercial aircraft.”

During outbreaks such as SARS and Ebola, countries have faced intense pressure to act on aviation procedures, though some argue the actions had more symbolic than scientific value.

For example, the SARS outbreak prompted airports in Asia to use thermal screening tools to measure the body heat of passengers before boarding flights. They were searching for people with high temperatures, since fever is often a sign that the immune system is fighting an illness.

Airports in China and Singapore have continued to use the scanners. Other airports around the world have used the scanners during other major outbreaks such as Ebola.

But critics believe the equipment does little to keep diseases from crossing borders by plane. For one thing, the scanners won’t detect a person who is infected but has not begun to show symptoms. For another, fever is such a common symptom that it can be a sign of dozens of diseases, or alternatively a symptom of the everyday stress of air travel.

“You have to screen many, many people to find anybody with an infectious disease,” said Michael T. Osterholm, author of the 2017 book, “Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs.” Osterholm noted that during the swine flu pandemic, the Mexico City airport used thermal scanners.

“There’s not a lick of evidence,” he said, “that it made one bit of difference in the movement of the virus in and around their country.”

He added that by the time health officials realized they were dealing with an outbreak of swine flu, the virus had already reached 27 countries.

Even the most extreme measures, such as restricting air traffic or closing national borders, may do more harm than good, experts say. Curbing air travel ends up slowing the flow of badly-needed medical supplies to an affected area. Closing borders to people from an outbreak region means telling aide workers who come to help that they may be unable to return home for months.

Lisa Rotz, CDC associate director for global health and migration, conceded that stopping diseases from spreading via air travel is a huge challenge. Even passengers who know they are sick often board planes rather than postponing plans.

“I would say it’s difficult to prevent completely,” Rotz said, “but there are a lot of things we can do to mitigate.”

For example, health care agencies have performed what she called “enhanced monitoring” during particularly serious outbreaks. In such cases, officials use scanners to detect potentially ill passengers departing from an affected area. Those who show elevated temperatures are then asked more detailed questions about their travel histories and symptoms.

In the years after Southwest Flight 703 to Mitchell, Biedrzycki — the Milwaukee health official — tried to address the shortcomings he’d seen, organizing a dry run of a similar health emergency.

The exercise took place in the spring of 2014. Forty officials from Southwest and Delta, the FBI, the Coast Guard, the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office, local hospitals and public health groups and the CDC all took part.

They met in a conference room at the Clarion Hotel near the airport. Biedrzycki and an expert he’d met at previous workshops, David J. Dausey, of Mercyhurst University in Erie, Penn., gave officials a scenario:

A full domestic flight, two hours from Milwaukee, has identified a sick passenger described as having a probable case of deadly Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

The attendees were given three tasks: first, decide which agencies to notify, what to tell them, and establish an incident command center; second, after the flight has landed, make an initial assessment and develop a response; third, based on what they learned during the exercise, develop a preliminary action plan and recommendations to improve local emergency planning.

As the exercise unfolded, officials ran into familiar problems, including jurisdictional disputes.

“Turf. Oh, God, yes,” said Biedrzycki. "I think a lot of them went in thinking that this (scenario) was a very low probability. Nothing ever happens in Milwaukee.”

Biedrzycki said he would have given the performance a grade of C+.

“I didn’t think it was phenomenal, but it was productive.”

Three years later he held a second exercise. This time the 35 officials who attended were given a “less exotic” disease to deal with: a case of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis on an inbound flight from Los Angeles.

Biedrzycki, who would retire from the Health Department a short time later, noticed a marked improvement the second time around. The airport issued an early alert to the local health department. Agencies did a better job of notifying one another, determining what information to give the public and establishing an emergency operations center at the airport.

Rotz of the CDC said she does not consider what happened with Flight 703 to be a quarantine, but more of a “temporary pause on movement.”

That the news got out before local health officials learned what was going on, she said was an unfortunate consequence of modern life.

“In this day and age, with cellphones on board, things get ahead of us,” she said.

In 2013, two years after the incident in Milwaukee, US Airways Flight 2846 landed at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, and the pilot announced to passengers: “We’ve been notified of a health emergency aboard the aircraft.”

“As passengers looked nervously at each other, one of the flight attendants approached a middle-aged male passenger, handed him a medical grade mask, and with emergency personnel in tow, escorted him from the plane,” according to an account given to the National Academy of Sciences.

“Another announcement followed a few minutes later informing passengers that the patient had active tuberculosis, was highly contagious and had exposed everyone aboard the flight.”

Then all of the passengers in Phoenix were confronted by a message that the passengers two years earlier in Milwaukee never had to hear.

“Please contact your physicians immediately.”