One of the most reviled figures from the civil war era in El Salvador, and a close ally of the United States, was a colonel and ex-minister of defense by the name of Nicolas Carranza. He died late last summer, on American soil, at the age of 84.

Carranza arrived in the U.S. in 1985 and became a full citizen seven years later. His wife and family settled in the suburbs of Memphis, where he quietly took a job as a security guard at a local art museum. In 2005, lawyers from a human rights group called the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) convinced a Memphis jury that Carranza was responsible for systematic torture and murder during the war. As the lead attorney put it at trial, Carranza had "exercised the real power in the high command" at a time when twelve-thousand unarmed civilians were killed by state security forces in a single year. Three plaintiffs who'd lost family members or were tortured themselves sought damages, and the jury awarded them $6 million. At the trial, Carranza was unrepentant, saying that his only regret was having worked for the Americans. He then confirmed what had long been assumed: he'd been on the CIA payroll for years.

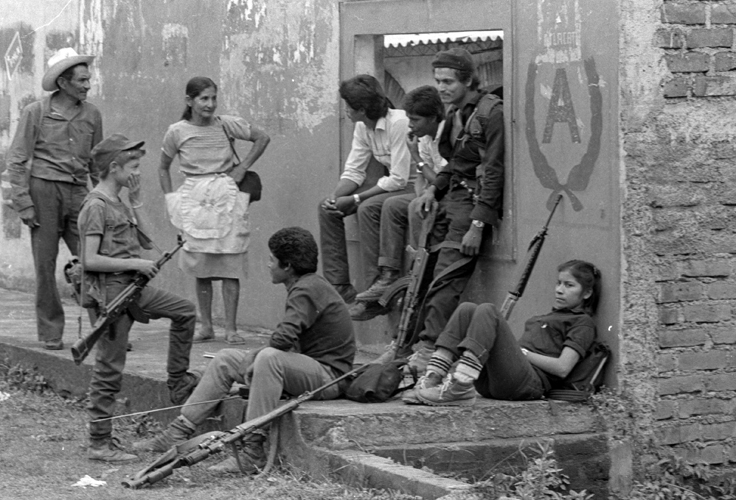

Throughout the 1980s, Carranza had ties to the extreme right in El Salvador. That meant something very specific at the time—he was involved with a band of vigilante death squads that tortured and killed suspected leftists across the country. Eventually, Carranza was forced out of his post in the military command, but two years later he became head of a repressive state security force called the Treasury Police. When his tenure there ended, he tried to leave the country for Spain, but the Spanish government wouldn't take him. I once asked a former American military advisor how it was possible for someone like Carranza to move so easily into the U.S. and become a citizen. "The answer is three letters long," he replied.

Carranza wasn't the only ex-Salvadoran military man to settle in the U.S. Two generals, who'd served as defense ministers, got green cards and moved to Florida. A soldier responsible for the murder of the legendary Archbishop Oscar Romero—one of the most famous crimes in recent Latin American history—relocated to Modesto, California, where he started selling used cars. Another ex-colonel, who was wanted for the assassination of six Jesuit priests in 1989, took a job outside Boston working in a factory that made candy.

For years, the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) brought civil charges against these men in American courts. (Until very recently, El Salvador had an amnesty law that blocked the prosecution of crimes committed during the war.) Each case brought by CJA cleared the way for a subsequent investigation by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Since then, the two ex-generals have been deported; Romero's assassin fled the country; and the ex-colonel involved in the Jesuit massacre was extradited to Spain.

Carranza's case was different. The civil trial may have been embarrassing to him, and his legal defense may have been costly, but the verdict didn't seem to lead anywhere. He and his family stayed put, in Memphis. "Here we have one of the biggest bad guys," Patty Blum, the former senior legal advisor to CJA, told Al Jazeera, in 2015; she'd been lobbying the government for close to a decade to take up the case. Because Carranza was a naturalized U.S. citizen, a human rights division at the Department of Justice needed to strip him of his citizenship before he could be considered for deportation. Yet every time a fresh crop of DOJ lawyers took the case on, it seemed to stall. I spoke to one of them, who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity. "I spent hours looking at Carranza's case file," he told me. "There was C.I.A. all over it. I had to go to Langley to even read it. It was made clear to us that this was not a case we could pursue."

The last time anyone had seen Carranza publicly was at his trial. But after the case had ended, and his lawyers began contesting the sum of the damages he had to pay, Carranza slipped into a fog of semi-notoriety. In the spring of 2016, I decided to visit him, in Memphis, to see if he'd be willing to talk. A few months before, the Salvadoran National Police launched a string of raids to arrest more than a dozen ex-officers for their role in killing the Jesuit priests three decades earlier. The sudden activity convulsed the country, and for weeks it was front-page news. I figured Carranza would have something to say, especially from his privileged American perch.

On a Monday afternoon in March, I pulled into a tidy, suburban neighborhood. The Carranzas lived in a tan-colored house with green shutters and a narrow front porch. Next to the front door was a small wooden plaque that said 'Bienvenido.' I hadn't told them I was coming.

When I rang the bell, Carranza's wife answered the door in a pink turtleneck and pearl earrings, her hair gray and neatly coiffed. Carranza stood behind her in an olive-colored fleece, light blue jeans and loafers. He cradled a barking chihuahua in his arms, and stared out with a drooping, fleshy face. The image reminded me of something a former political prisoner in El Salvador had once told me. "It's satisfying to see the military guys reduced in their power all these years later," he'd said. "And yet seeing them like this, all reduced in stature, just means they've been allowed to grow old."

Carranza's wife stepped outside to intercept me, closing the door behind her. I told her who I was and that I hoped to speak to her husband. "I'm sorry, but we've just been back from the doctor," she said. "He's not having a good day."

I had heard from a local lawyer that he'd had health problems, but I had no idea it was something so debilitating. Carranza was suffering from late-stage Alzheimer's. "It's very painful for a wife," she went on. "He was once a politician of a very high rank in my country." Her English was thickly accented but fluent—clean and forceful. We switched into Spanish, and eventually came to an agreement. She would let me go inside to greet her husband, but I couldn't ask him any questions about the past. If he wanted to reminisce, that would be fine, but I couldn't provoke him.

Carranza was waiting at the back of the living room, staring out a sliding glass door that gave onto a modest backyard. An enormous television played the news. President Obama was on the screen alongside Raul Castro. It was the day of their historic Havana summit.

Carranza shuffled over to shake my hand, his wife coaxing him to me. "I apologize for any imprecisions in my speech. I'm trying…" he said, then looked helplessly toward his wife, who nodded reassuringly. "I used to know people in Cuba, military guys," he said. His wife motioned to the television and scowled; she didn't approve of any rapprochement with the Castros. Carranza tried to say more on this, but the words came out garbled. His wife, taking the cue, interceded and ushered me out through the front door.

She calmly let me finish as I told her why I wanted to talk to him again the next day. "Thank you, but no," she said. "We've already spent all of our money on lawyers. My husband believes in God. He did nothing wrong. All he did was hate communists."

Education Resource

Meet the Journalist: Jonathan Blitzer

Pulitzer Center grantee Jonathan Blitzer covers the impact deportation has had on Salvadorans who...