When two people in white protective gear entered Siddique’s three-room apartment in Kuala Lumpur on 11 May, he thought they were medical personnel. Then he noticed “POLIS” written on the backs of their uniforms. “They searched every corner, [to see] if anyone was hiding. Only then did I understand that a raid was happening,” says Siddique, a Rohingya refugee from Myanmar who has lived in Malaysia for 13 years.

Siddique is one of 180,000 refugees and asylum seekers registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Malaysia, a country which has not ratified the UN refugee convention and considers refugees “illegal immigrants”. Refugee community groups estimate that 80,000 more await UNHCR registration interviews, which can take years to complete, leaving them undocumented in the meantime.

Since 1 May, Malaysia’s immigration department and police force have carried out immigration raids in Kuala Lumpur, sending more than 2,200 people to detention centres, where COVID-19 cases have since exploded. Following detection of the first detention centre cluster on 22 May, 680 cases were reported across four facilities as of 4 June. While those registered with UNHCR have largely been spared arrest, unregistered asylum seekers have been swept up along with undocumented migrant workers.

During the 11 May raid, which occurred in the neighbourhood surrounding the Selayang Wholesale Market, Siddique recalls police officers escorting him, his wife and three children onto the street, where they joined thousands of others in an “identity verification” exercise which ended with more than 1,300 people arrested.

“It was like hell, witnessing immigrants and refugees gathered by authorities,” says Siddique, who saw women separated from husbands they had recently joined in Malaysia. “Some were pregnant and some were with toddlers. They were screaming for help while their husbands stared at them helplessly and wept.”

The raid, and the three which preceded it on 1 May and 3 May, all came on the last day of two-week lockdowns accompanied by comprehensive COVID-19 testing. Placed over specific neighbourhoods with coronavirus case clusters, the lockdowns are a stricter form of a nationwide Movement Control Order (MCO), which from 18 March to 3 May mandated the closing of all nonessential businesses and restricted movement to necessary solo travel during daytime hours.

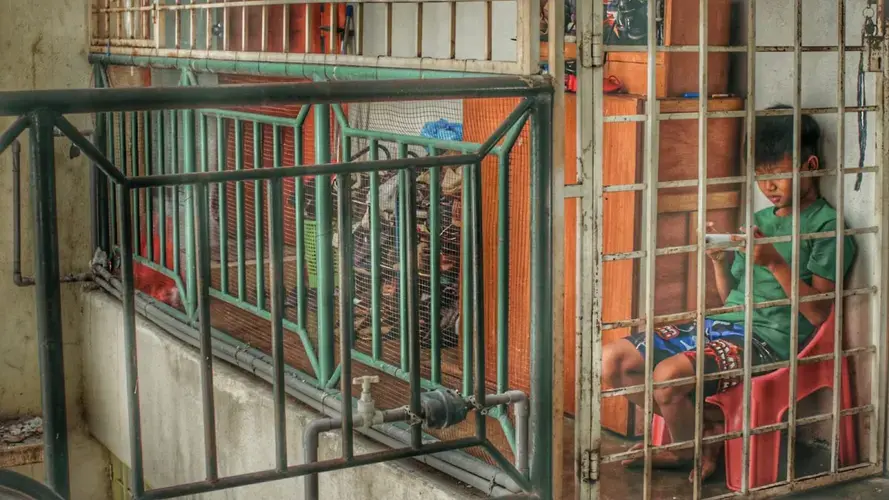

Areas under lockdown are surrounded by barbed wire, with residents forbidden from leaving their homes. “I felt like we were living in a cage,” says Siddique, whose family relied on food donations from local aid groups and rice, oil and flour provided by the government during the two-week period.

In addition to experiencing nightmares about the lockdown period and raids, Siddique faces mounting worries about the future. On 19 March, he suddenly had to close the two vegetable stalls he operated through an informal agreement with the stalls’ owner. The shops were near Pasar Lama, one of two large wholesale markets in the area, and were closed under regulations imposed by the MCO. Although the stalls’ owner told Siddique authorities had delivered a closure notice five days prior, Siddique says he never received it. He lost approximately RM 7,000 (US$1,630) in unsold produce.

When the Selayang Wholesale Market and other wholesale markets around the city reopened, authorities banned all foreign workers, regardless of their immigration status, from entering, under a new government order—despite reports that authorities have faced difficulty finding locals willing to take the jobs.

With refugees excluded from Malaysia’s COVID-19 relief package, Siddique has few places to turn to for support. During Ramadan, he skipped suhur, the meal eaten before sunrise, and ate only once a day; he also owes RM 2,250 (about US$525) for the past three months’ rent. “My landlady keeps scolding me, but I am silent as I have no words to say,” he tells New Naratif. “How would I pay her when I can’t even support my family with food?”

Malaysia has seen a wave of online hate speech towards migrants and refugees, and particularly Rohingya, since late April, accompanied by government announcements and policies hostile towards migrants and refugees. On June 7, the government announced that only Malaysians would be allowed to attend Friday prayer at mosques around the country, following which sign boards saying ‘We are Not Welcoming Rohingya’ appeared in front of a mosque in the state of Johor. The government has also made announcements targeting the Rohingya as “illegal immigrants” and denied entry of boats carrying Rohingya, seeking refuge. At the end of May, Malaysia announced that the amnesty period granted to migrants coming forward for testing, which had been offered on 22 March, was over.

“It’s a scary time for refugees,” Siddique says. “Seeing the recent hatred and vitriolic comments on social media against Rohingya, fear has grown in my mind.”

“We are not respected and I feel I would rather die than live as a refugee in a foreign country where I don’t have a dignified life.”

An Immigration Crackdown

Nyi Linn Twan, 23, is from the same township as Siddique—Kyauktaw in Rakhine State, Myanmar. An ethnic Rakhine, he came to Malaysia in 2017, and is still awaiting a registration appointment with UNHCR.

Undocumented, he has left his apartment as little as possible since the MCO went into effect, and was let go from his restaurant job on 12 May after failing to go in for the COVID-19 test mandated by the Ministry of Health for anyone returning to work.

“Without the test certificate, I cannot work. As I do not have any documents, I am afraid to even leave my house,” he says. He is now relying on donations from other refugees to survive.

On 12 May, Malaysia announced that those arrested for violating the country’s immigration laws would be deported and blacklisted. The same day, Malaysia deported nearly 400 Myanmar nationals, and on 8 June, announced intent to deport more than 3,000 people in immigration detention centres back to Myanmar.

Deportation is a scary possibility for Nyi Linn Twan.

In late 2017, Rakhine State saw the mass exodus of more than 700,000 Rohingya Muslims following a brutal campaign of killing, arson and violence at the hands of the Myanmar military. Now, ethnic Rakhine Buddhists in the state, as well as Chin in neighboring Chin State, are suffering from similar patterns of violence. Since late 2018, conflict between the Arakan Army—a rebel army fighting for autonomy for the ethnic Rakhine—and the Myanmar military has intensified, displacing more than 157,000 people, while Rakhine young men bear the particular risk of being accused of collaborating with the Arakan Army. Kyauktaw township, where Nyi Linn Twan is from, is a particular hotspot for the conflict.

The government has imposed an internet shutdown in townships including Kyauktaw since June 2019, and Nyi Linn Twann has had difficulty contacting his family. He fears his life will be in danger were he to be sent back. “I feel that I am wandering in the darkness…I really worry about how long I will survive these hardships,” he says.

Fear also pervades the life of Hkawng Ja*, an undocumented asylum seeker from Myanmar’s Kachin State.

On the night of 14 May, she looked out of her window in Kuala Lumpur’s Pudu neighbourhood to see police encircling nearby streets with barbed wire to prevent residents from leaving the area—part of lockdown measures placed over areas with clusters of COVID-19 cases. Having heard of raids following lockdowns in other parts of the city, Hkawng Ja could not sleep.

Hkawng Ja was not just worried about herself, but also her husband, son and mother. A few months after reaching Malaysia in 2014, her husband began suffering from mental illness and was hospitalised for more than a month. “Because of [my husband’s] illness, we cannot live in peace. We have to watch him all the time,” she says.

In 2018, her family attended refugee status determination interviews with UNHCR, requiring Hkawng Ja, her husband and son to individually recount their stories. “At the time, my husband’s condition was very bad,” she says. “Unfortunately, his answers and our answers did not match.” Her family’s application was rejected and their appeal was denied, according to Hkawng Ja.

In October 2019, Hkawng Ja was arrested on the way home from work and spent the next 10 days in a police station. “When I thought about my family at home who could get arrested any time, my own situation in jail, and not being able to work or take care of my family, I took off my clothes and wanted to hang myself,” she says.

Her employer and a relative paid RM5,000 (US$1,170) for her release and she resumed work, but struggled to cope. “My fear of police after the arrest became indescribable. I was traumatised by the experience in jail. The fear is always with me,” she says.

The nail salon where Hkawng Ja worked closed under the MCO. Her family has since relied on community donations for their basic food and material needs.

The day after Hkawng Ja saw police laying down the barbed wire, a two-week semi-lockdown was announced on parts of Pudu, with residents only allowed to move within the fenced-in area. Her home just a few houses outside of the fenced-in area, she decided to move her family with help from a community volunteer as a pre-emptive measure. “The [new] house is not in good condition, and the water supply cuts off at 10 a.m. We have just a few of our belongings and left all our food behind…but this difficulty is nothing. We feel safer here,” she told New Naratif a few days after moving.

But she doesn’t expect the feeling to last. “It is as if my family is destined to live in fear forever…Because we don’t have UNHCR cards, we cannot live safely or work. Now we have no income and are running away from the danger of arrest. I feel hopeless.”

Life Under Lockdown

Peter Thang, a Chin refugee from Myanmar who has lived in Malaysia since 2011, spoke with New Naratif by phone on 22 May. He lives in the part of Pudu that was under semi-lockdown and says that whenever his two children heard sirens, they ran to the window and asked whether police were coming to arrest them. “I try to comfort them and mention God is with us, but I worry about their mental well-being,” he told New Naratif by phone while he was living under lockdown.

Within the fenced-in area, authorities conducted COVID-19 swab tests and collected residents’ biodata and fingerprints. When Peter took his children for screening on 16 May, it was their first time leaving the building in two months.

“My children ask me when they can go out. They want to go to places like Times Square and Kuala Lumpur City Centre…they want to visit their friends,” he says. Instead, to get some fresh air during the MCO, he took them to the rooftop of his apartment building.

His children are also missing out on their education. Refugees in Malaysia are not permitted to attend government schools, and the refugee-run community school which Peter’s children attended is not offering online classes. Peter and his wife are trying to fill the gap, but he fears his children have regressed.

Food was another concern during the semi-lockdown. Although some shops remained open, fresh produce and meat were scarce, says Peter, and his family primarily ate potatoes and dried goods.

Mika*, from Myanmar’s Mon state, moved to Malaysia in 2013 with her then four-year-old daughter and eleven-year-old younger brother. Mika and her family are registered asylum seekers, but she says she still lives in fear after seeing the continued arrests of migrants and refugees in recent months.

During the semi-lockdown, Mika says she did not dare go outside and relied on donations of dried goods. She and her family did not have any fresh produce during the two-week period, and mainly ate potatoes and eggs.

As with Peter’s family, the few times Mika and her family went outside were at the request of authorities. People dressed in white protective suits came to her apartment three times and brought her family outside for nasal swabs, fingerprinting and throat swabs. Mika says she never received the results.

The hair salon where Mika worked closed when the MCO went into effect in mid-March, and her employer has covered her rent costs since then. She is eager to resume working, but with the government repeatedly warning employers not to hire undocumented foreigners, she is concerned she may lose her job.

Pudu was not raided as Peter and Mika had feared, raising the question as to whether further raids will occur, but semi-lockdowns were placed on three other areas with migrant populations on 3 June following the emergence of several new virus clusters.

A Call for Acceptance

Malaysia initially justified the raids as a COVID-19 containment measure, but on 12 May the government said the raids were part of a continuous effort to weed out undocumented foreigners.

Language and policies targeting foreigners, as well as the online hate speech that has followed, are particularly distressing for Hasnah Hussin, a Rohingya refugee born in Malaysia who works as a community mobiliser for the migrant rights group Tenaganita. “It is really painful to see children, women and disabled people arrested and detained…and [others] continuing to live in endless fear,” she says.

Hasnah Hussin says she has never experienced the current level of hostility towards refugees during her lifetime. “I feel extremely sad because I have seen and lived among Malaysians who have been so supportive, protective, respectful and loving.”

Yet seeing refugees’ resilience in recent months, as well as the commitment of Malaysian advocates who have spoken out in solidarity, has given her optimism.

“I never lose hope that once people know the actual situation and reality of refugees and migrants’ stories and struggles, they will understand why we ended up here [in Malaysia] for the time being,” she says. “I have seen the beautiful colors of Malaysia and I believe Malaysia still has these colors.”

Additional reporting by Zau Myet Awng and Nu Nu

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of the refugees

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.