How 14 land grant colleges took 8.2 million acres from 123 Indigenous nations.

Alina Sierra needs $6,405. In 2022, the 19-year-old Tohono O’odham student was accepted to the University of Arizona, her dream school, and excited to become the first in her family to go to college.

Her godfather used to take her to the university’s campus when she was a child, and their excursions could include a stop at the turtle pond or lunch at the student union. Her grandfather also encouraged her, saying: “You’re going to be here one day.”

“Ever since then,” said Sierra. “I wanted to go.”

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund coverage of Indigenous issues and communities. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Then the financial reality set in. Unable to afford housing either on or off campus, she couch-surfed her first semester. Barely able to pay for meals, she turned to the campus food pantry for hygiene products. “One week I would get soap; another week, get shampoo,” she said. Without reliable access to the internet, and with health issues and a long bus commute, her grades began to slip. She was soon on academic probation.

“I always knew it would be expensive,” said Sierra. “I just didn’t know it would be this expensive.”

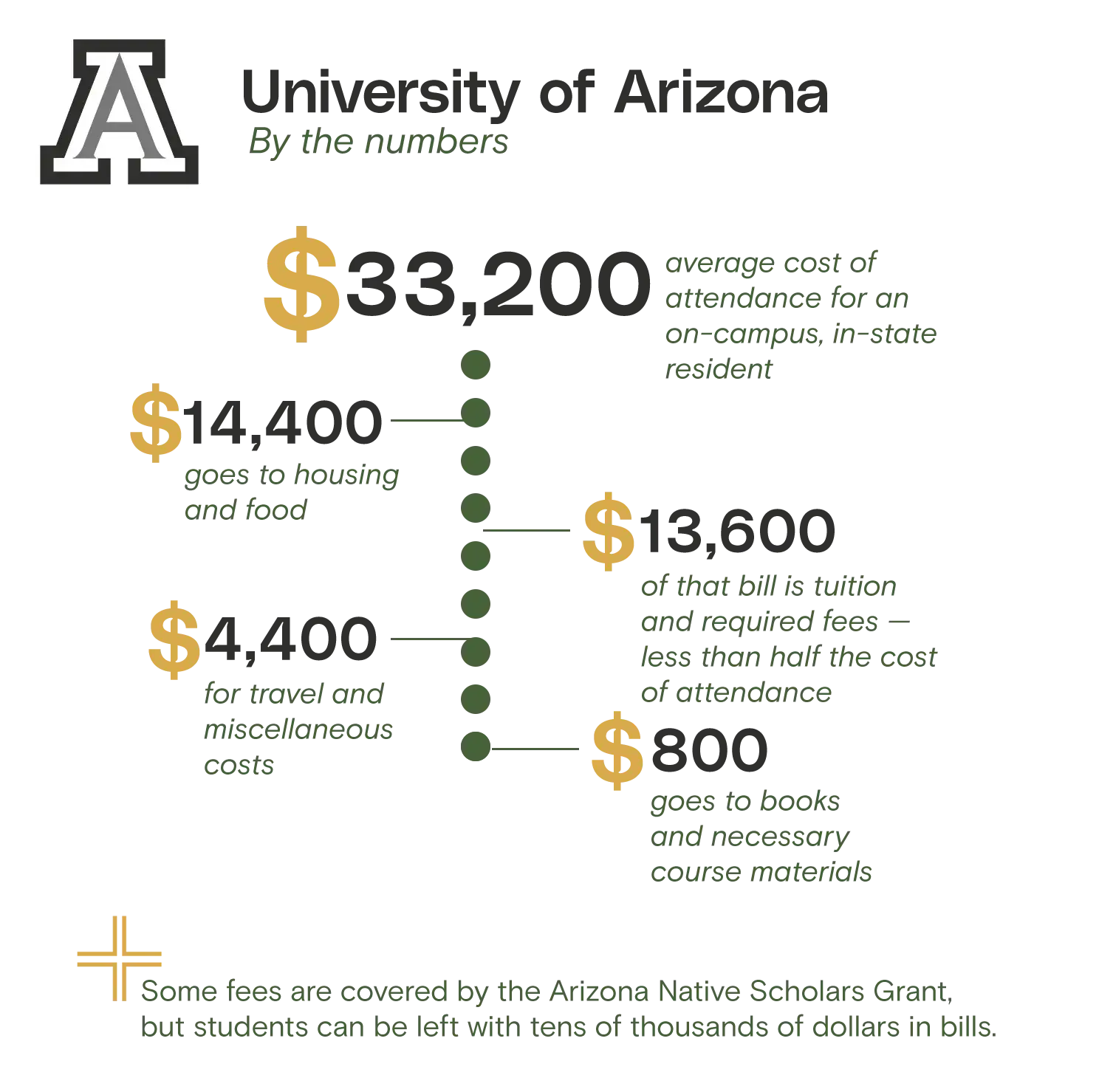

She was also confused. The university, known colloquially as UArizona, expressed a lot of support for Indigenous students. It wasn’t just that the Tohono O’odham flag hung in the bookstore or that the university had a land acknowledgment reminding the community that the Tucson campus was on O’odham and Yaqui homelands. The same year she was accepted, UArizona launched a program to cover tuition and mandatory fees for undergraduates from all 22 Indigenous nations in the state. President Robert C. Robbins described the new Arizona Native Scholars Grant as a step toward fulfilling the school’s land-grant mission.

Sierra was eligible for the grant, but it didn’t cover everything. After all the application forms and paperwork, she was still left with a balance of thousands of dollars. She had no choice but to take out a loan, which she kept a secret from her family, especially her mom. “That’s the number one thing she told me: ‘Don’t get a loan,’ but I kind of had to.”

Established in 1885, almost 30 years before Arizona was a state, UArizona was one of 52 land-grant universities supported by the Morrill Act. Signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, the act used land taken from Indigenous nations to fund a network of colleges across the fledgling United States.

By the early 20th century, grants issued under the Morrill Act had produced the modern equivalent of a half a billion dollars for land-grant institutions from the redistribution of nearly 11 million acres of Indigenous lands. While most land-grant universities ignore this colonial legacy, UArizona’s Native scholars program appeared to be an effort to exorcise it.

But the Morrill Act is only one piece of legislation that connects land expropriated from Indigenous communities to these universities.

In combination with other land-grant laws, UArizona still retains rights to nearly 687,000 acres of land — an area more than twice the size of Los Angeles. The university also has rights to another 703,000 subsurface acres, a term pertaining to oil, gas, minerals, and other resources underground. Known as trust lands, these expropriated Indigenous territories are held and managed by the state for the school’s continued benefit.

State trust lands just might be one of the best-kept public secrets in America: They exist in 21 Western and Midwestern states, totaling more than 500 million surface and subsurface acres. Those two categories, surface and subsurface, have to be kept separate because they don’t always overlap. What few have bothered to ask is just how many of those acres are funding higher education.

The parcels themselves are scattered and rural, typically uninhabited and seldom marked. Most appear undeveloped and blend in seamlessly with surrounding landscapes. That is, when they don’t have something like logging underway or a frack pad in sight.

In 2022, the year Sierra enrolled, UArizona’s state trust lands provided the institution $7.7 million — enough to have paid the full cost of attendance for more than half of every Native undergraduate at the Tucson campus that same year. But providing free attendance to anyone is an unlikely scenario, as the school works to rein in a budget shortfall of nearly $240 million.

UArizona’s reliance on state trust land for revenue not only contradicts its commitment to recognize past injustices regarding stolen Indigenous lands, but also threatens its climate commitments. The school has pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2040.

The parcels are managed by the Arizona State Land Department, a separate government agency that has leased portions of them to agriculture, grazing, and commercial activities. But extractive industries make up a major portion of the trust land portfolio. Of the 705,000 subsurface acres that benefit UArizona, almost 645,000 are earmarked for oil and gas production. The lands were taken from at least 10 Indigenous nations, almost all of which were seized by executive order or congressional action in the wake of warfare.

Over the past year, Grist has examined publicly available data to locate trust lands associated with land-grant universities seeded by the Morrill Act. We found 14 universities that matched this criteria. In the process, we identified their original sources and analyzed their ongoing uses. In all, we located and mapped more than 8.2 million surface and subsurface acres taken from 123 Indigenous nations. This land currently produces income for those institutions.

“Universities continue to benefit from colonization,” said Sharon Stein, an assistant professor of higher education at the University of British Columbia and a climate researcher. “It’s not just a historical fact; the actual income of the institution is subsidized by this ongoing dispossession.”

To view the infographic "Indigenous Land Granted to Universities," click here.

The amount of acreage under management for land-grant universities varies widely, from as little as 15,000 acres aboveground in North Dakota to more than 2.1 million belowground in Texas. Combined, Indigenous nations were paid approximately $4.3 million in today’s dollars for these lands, but in many cases, nothing was paid at all. In 2022 alone, these trust lands generated more than $2.2 billion for their schools. Between 2018 and 2022, the lands produced almost $6.7 billion. However, those figures are likely an undercount as multiple state agencies did not return requests to confirm amounts.

This work builds upon previous investigations that examined how land grabs capitalized and transformed the U.S. university system. The new data reveals how state trust lands continue to transfer wealth from Indigenous nations to land-grant universities more than a century after the original Morrill Act.

It also provides insight into the relationship between colonialism, higher education, and climate change in the Western United States.

Nearly 25 percent of land-grant university trust lands are designated for either fossil fuel production or the mining of minerals, like coal and iron-rich taconite. Grazing is permitted on about a third of the land, or approximately 2.8 million surface acres. Those parcels are often coupled with subsurface rights, which means oil and gas extraction can occur underneath cattle operations, themselves often a major source of methane emissions. Timber, agriculture, and infrastructure leases — for roads or pipelines, for instance — make up much of the remaining acreage.

By contrast, renewable energy production is permitted on roughly one-quarter of 1 percent of the land in our dataset. Conservation covers an even more meager 0.15 percent.

However, those land use statistics are likely undercounts due to the different ways states record activities. Many state agencies we contacted for this story had incomplete public information on how land was used.

“People generally are not eager to confront their own complicity in colonialism and climate change,” said Stein. “But we also have to recognize, for instance, myself as a white settler, that we are part of that system, that we are benefiting from that system, that we are actively reproducing that system every day.”

Students like Alina Sierra struggle to pay for education at a university built on her peoples’ lands and supported with their natural resources. But both current and future generations will have to live with the way trust lands are used to subsidize land-grant universities.

In December 2023, Sierra decided the cost to attend UArizona was too high and dropped out.

UArizona did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

Acreage now held in trust by states for land-grant universities is part of America’s sweeping history of real estate creation, a history rooted in Indigenous dispossession.

Trust lands in most states were clipped from the more than 1.8 billion acres that were once part of the United States’ public domain — territory claimed, colonized, and redistributed in a process that began in the 18th century and continues today.

The making of the public domain is the stuff of textbook lessons on U.S. expansion. After consolidating states’ western land claims in the aftermath of the American Revolution, federal officials obtained a series of massive territorial acquisitions from rival imperial powers. No doubt you’ve heard of a few of these deals: They ranged from the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 to the Alaska Purchase of 1867.

Backed by the doctrine of discovery, a legal principle with religious roots that justified the seizure of lands around the world by Europeans, U.S. claims to Indigenous territories were initially little more than projections of jurisdiction. They asserted an exclusive right to steal from Indigenous nations, divide the territory into new states, and carve it up into private property. Although Pope Francis repudiated the Catholic Church’s association with the doctrine in 2023, it remains a bedrock principle of U.S. law.

Starting in the 1780s, federal authorities began aggressively taking Native land before surveying and selling parcels to new owners. Treaties were the preferred instrument, accompanied by a range of executive orders and congressional acts. Behind their tidy legal language and token payments lay actual or threatened violence, or the use of debts or dire conditions, such as starvation, to coerce signatures from Indigenous peoples and compel relocation.

By the 1930s, tribal landholdings in the form of reservations covered less than 2 percent of the United States. Most were located in places with few natural resources and more sensitive to climate change than their original homelands. When reservations proved more valuable than expected, due to the discovery of oil, for instance, outcomes could be even worse, as viewers of Killers of the Flower Moon learned last year.

The public domain once covered three-fourths of what is today the United States. Federal authorities still retain about 30 percent of this reservoir of plundered land, most conspicuously as national parks, but also as military bases, national forests, grazing land, and more. The rest, nearly 1.3 billion acres, has been redistributed to new owners through myriad laws.

When it came to redistribution, grants of various stripes were more common than land sales. Individuals and corporate grantees — think homesteaders or railroads — were prominent recipients, but in terms of sheer acreage given, they trailed a third group: state governments.

Federal-to-state grants were immense. Cram them all together and they would comfortably cover all of Western Europe. Despite their size and ongoing financial significance, they have never attracted much attention outside of state offices and agencies responsible for managing them.

The Morrill Act, one of the best known examples of federal-to-state grants, followed a well-established path for funding state institutions. This involved handing Indigenous land to state legislatures so agencies could then manage those lands on behalf of specifically chosen beneficiaries.

Many other laws subsidized higher education by issuing grants to state or territorial governments in a similar way. The biggest of those bounties came through so-called “enabling acts” that authorized U.S. territories to graduate to statehood.

Every new state carved out of the public domain in the contiguous United States received land grants for public institutions through their enabling acts. These grants functioned like dowries for joining the Union and funded a variety of public works and state services ranging from penitentiaries to fish hatcheries. Their main function, however, was subsidizing education.

Since time immemorial, Indigenous peoples have lived with, and cared for, the lands they call home.

But as settlers moved west, U.S. government and military officials forced those communities from their lands, sometimes through the signing of treaties, sometimes through military action.

Once ceded, those lands became territories and then states. With statehood, those lands became part of America's real estate system.

Lands inside newly formed states were overlaid with the Public Land Survey System — a rectangular survey system designed by early colonists to map newly acquired Indigenous lands.

One 6-by-6 mile square on the grid is known as a township.

Inside each township are 36 more 1-by-1 mile squares called sections.

In most states, sections 16 and 36 of every township were automatically set aside to fund K-12 schools, known as common schools at the time.

From the remaining 34 sections, states could choose which lands would benefit other public institutions, like hospitals, penitentiaries, and universities.

In the years since statehood, some of these lands have been sold or swapped, but most Western states have held onto their trust lands.

Spread across the Western U.S. land grid, trust lands are often unseen, landlocked, and anonymous on the landscape.

To view an interactive map, click here.

Primary and secondary schools, or K-12 schools, were the greatest beneficiaries by far, followed by institutions of higher education. What remains of them today are referred to as trust lands. “A perpetual, multigenerational land trust for the support of the Beneficiaries and future generations” is how the Arizona State Land Department describes them.

Higher education grants were earmarked for universities, teachers colleges, mining schools, scientific schools, and agricultural colleges, the latter being the means through which states that joined the Union after 1862 got their Morrill Act shares. States could separate or consolidate their benefits as they saw fit, which resulted in many grants becoming attached to Morrill Act colleges.

Originally, the land was intended to be sold to raise capital for trust funds. By the late 19th century, however, stricter requirements on sales and a more conscientious pursuit of long-term gains reduced sales in favor of short-term leasing.

The change in management strategy paid off. Many state land trusts have been operating for more than a century. In that time, they have generated rents from agriculture, grazing, and recreation. As soon as they were able, managers moved into natural resource extraction, permitting oil wells, logging, mining, and fracking.

Land use decisions are typically made by state land agencies or lawmakers. Of the six land-grant institutions that responded to requests for comment on this investigation, those that referenced their trust lands deferred to state agencies, making clear that they had no control over permitted activities.

To view the infographic "What Happens on State Trust Lands," click here.

State agencies likewise receive and distribute the income. As money comes in, it is either delivered directly to beneficiaries or, more commonly, diverted to permanent state trust funds, which invest the proceeds and make scheduled payouts to support select public services and institutions.

These trusts have a fiduciary obligation to generate profit for institutions, not minimize environmental damage. Although some of the permitted activities are renewable and low-impact, others are quietly stripping the land. All of them fill public coffers with proceeds derived from ill-gotten resources.

For a $10 fee last December, anyone in New Mexico could chop down a Christmas tree in a pine stand on a patch of state trust land just off Highway 120 near Black Lake, southeast of Taos. The rules: Pay your fee, bring your permit, choose a tree, and leave nothing behind but a stump less than 6 inches high.

“The holidays are a time we should be enjoying our loved ones, not worrying about the cost of providing a memorable experience for our kids,” said Commissioner of Public Lands Stephanie Garcia Richard, adding that “the nominal fee it costs for a permit will directly benefit New Mexico public schools, so it supports a good cause too.” The offer has been popular enough to keep the program running for several years.

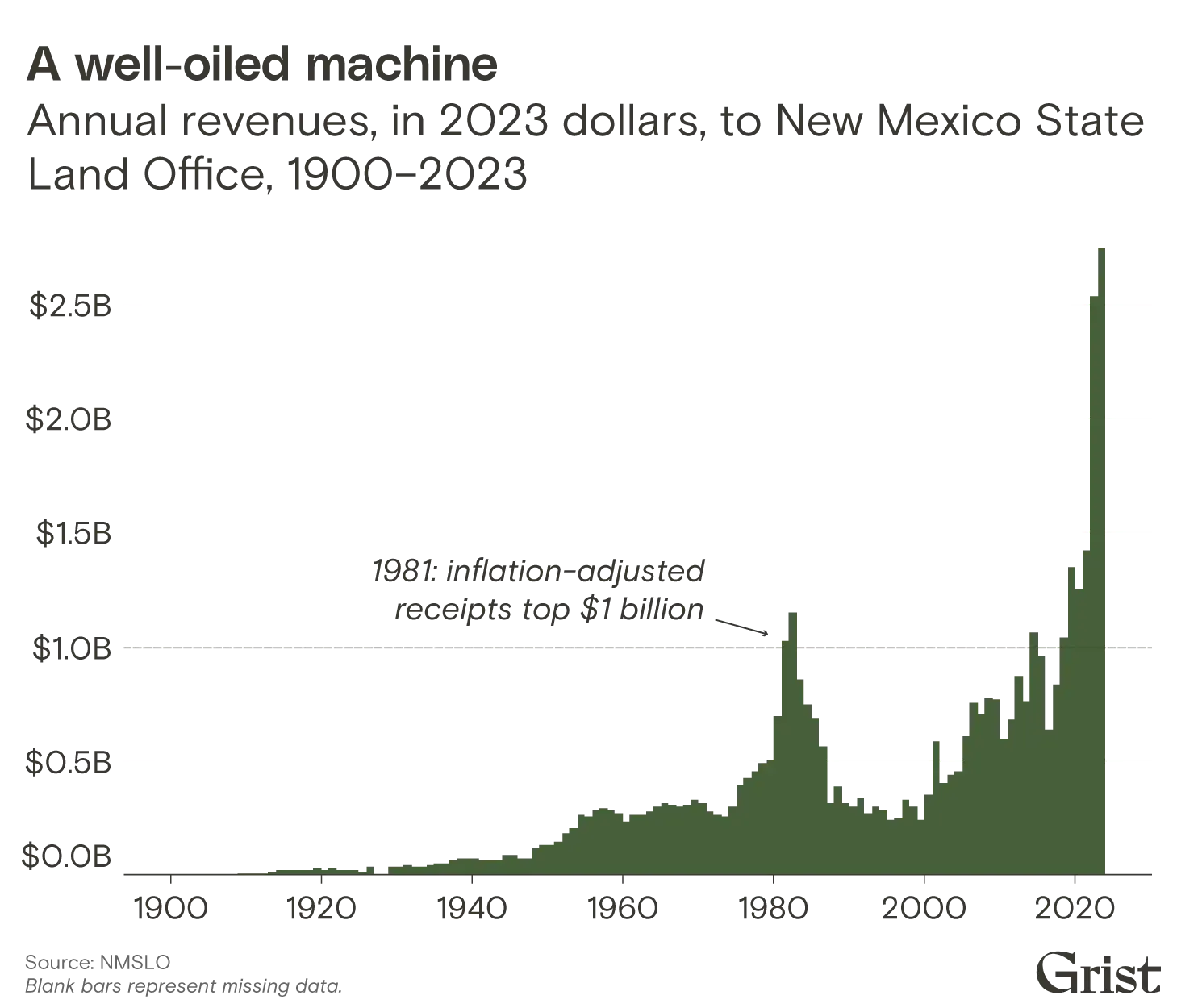

The New Mexico State Land Office, sometimes described by state legislators as “the most powerful office you’ve never heard of,” has been a successful operation for a very long time. Since it started reporting revenue in 1900, it’s generated well over $42 billion in 2023 dollars.

All that money isn’t from Christmas trees.

For generations, oil and gas royalties have fueled the state’s trust land revenue, with a portion of the funds designated for New Mexico State University, or NMSU, a land-grant school founded in 1888 when New Mexico was still a territory.

The oil comes from drilling in the northwestern fringe of the Permian Basin, one of the oldest targets of large-scale oil production in the United States. Corporate descendants of Standard Oil, the infamous monopoly controlled by John D. Rockefeller, were operating in the Permian as early as the 1920s. Despite being a consistent source of oil, prospects for exploitation dimmed by the late 20th century, before surging again in the 21st. Today, it’s more profitable than ever.

In recent decades, more sophisticated exploration techniques have revealed more “recoverable” fossil fuel in the Permian than previously believed. A 2018 report by the United States Geological Survey pegged the volume at 46.3 billion barrels of oil and 281 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, which made the Permian the largest oil and gas deposit in the nation. Analysts, shocked at the sheer volume, and the money to be made, have taken to crowning the Permian the “King of Shale Oil.” Critics concerned with the climate impact of the expanding operations call it a “carbon bomb.”

As oil and gas extraction spiked, so did New Mexico’s trust land receipts. In the last 20 years, oil and gas has generated between 91 and 97 percent of annual trust land revenue. It broke annual all-time highs in half of those years, topping $1 billion for the first time in 2019 and reaching $2.75 billion last year. Adjusted for inflation, more than 20 percent of New Mexico’s trust land income since 1900 has arrived in just the last five years.“

Every dollar earned by the Land Office,” Commissioner Richard said when revenues broke the billion-dollar barrier, “is a dollar taxpayers do not have to pay to support public institutions.”

Trust land as a cost-free source of subsidies for citizens is a common framing. In 2023, Richard declared that her office had saved every New Mexico taxpayer $1,500 that year. The press release did not mention oil or gas, or Apache bands in the state.

Virtually all of the trust land in New Mexico, including 186,000 surface acres and 253,000 subsurface acres now benefiting NMSU, was seized from various Apache bands during the so-called Apache Wars. Often reduced to the iconic photograph of Geronimo on one knee, rifle in hand, hostilities began in 1849, and they remain the longest-running military conflict in U.S. history, continuing until 1924.

In 2019, newly elected New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham began aligning state policy with “scientific consensus around climate change.” According to the state’s climate action website, New Mexico is working to tackle climate change by transitioning to clean electricity, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, supporting an economic transition from coal to clean energy, and shoring up natural resource resilience.

“New Mexico is serious about climate change — and we have to be. We are already seeing drier weather and rising temperatures,” the governor wrote on the state’s website. “This administration is committed not only to preventing global warming, but also preparing for its effects today and into the future.”

No mention was made of increasingly profitable oil and gas extraction on trust lands or their production in the Permian. In 2023, just one 240-acre parcel of land benefiting NMSU was leased for five years for $6 million.

NMSU did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

More than half of the acreage uncovered in our investigation appears in oil-rich West Texas, the equivalent of more than 3 million football fields. It benefits Texas A&M.

Take the long drive west along I-10 between San Antonio and El Paso, in the southwest region of the Permian Basin, and you’ll pass straight through several of those densely packed parcels without ever knowing it — they’re hidden in plain sight on the arid landscape. These tracts, and others not far from the highway, were Mescalero Apache territory. Kiowas and Comanches relinquished more parcels farther north.

In the years after the Civil War, a “peace commission” pressured Comanche and Kiowa leaders for an agreement that would secure land for tribes in northern Texas and Oklahoma. Within two years, federal agents dramatically reduced the size of the resulting reservation with another treaty, triggering a decade of conflict.

The consequences were disastrous. Kiowas and Comanches lost their land to Texas and their populations collapsed. Between the 1850s and 1890s, Kiowas lost more than 60 percent of their people to disease and war, while Comanches lost nearly 90 percent.

If this general pattern of colonization and genocide was a common one, the trajectory that resulted in Texas A&M’s enormous state land trust was not.

Texas was never part of the U.S. public domain. Its brief stint as an independent nation enabled it to enter the Union as a state, skipping territorial status completely. As a result, like the original 13 states, it claimed rights to sell or otherwise distribute all the not-yet-privatized land within its borders.

Following the broader national model, but ratcheting up the scale, Texas would allocate over 2 million acres to subsidize higher education.

Texas A&M was established to take advantage of a Morrill Act allocation of 180,000 acres, and opened its doors in 1876. The same year, Texas allocated a million acres of trust lands, followed by another million in 1883, nearly all of it on land relinquished in treaties from the mid-1860s.

To view the infographic "A Texas-sized Trust," click here.

Today, the Permanent University Fund derived from that land is worth nearly $34 billion. That’s thanks to oil, of course, which has been flowing from the university’s trust lands since 1923. In 2022 alone, Texas trust lands produced $2.2 billion in revenue.

The Kiowa and Comanche were ultimately paid about 2 cents per acre for their land. The Mescalero Apache received nothing.

Texas A&M did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

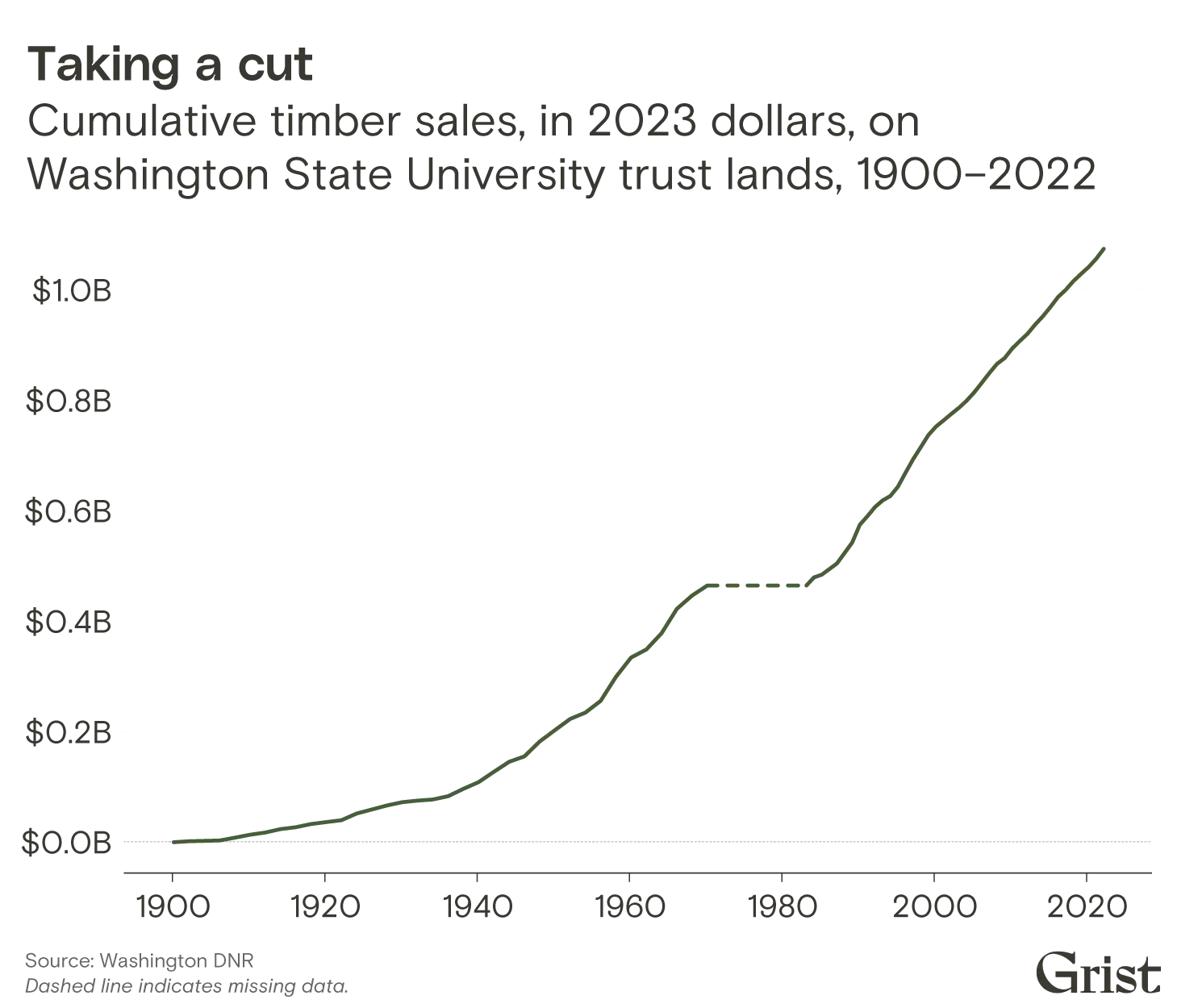

For more than a century, logging has been the main driver of Washington State University’s trust land income, on land taken from 21 Indigenous nations, especially the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. About 86,000 acres, more than half of the surface trust lands allocated to Washington State University, or WSU, are located inside Yakama land cessions, which started in 1855. Between 2018 and 2022, trust lands produced nearly $78.5 million in revenue almost entirely from timber.

But it isn’t a straight line to the university’s bank account.

“The university does not receive the proceeds from timber sales directly,” said Phil Weiler, a spokesperson for WSU. “Lands held in trust for the university are managed by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, not WSU.”

In 2022, WSU’s trust lands produced about $19.5 million in revenue, which was deposited into a fund managed by the State Investment Board. In other words, the state takes on the management responsibility of turning timber into investments, while WSU reaps the rewards by drawing income from the resulting trust funds.

“The Washington legislature decides how much of the investment earnings will be paid out to Washington State University each biennium,” said Weiler. “By law, those payouts can only be used to fund capital projects and debt service.”

This arrangement yielded nearly $97 million dollars for WSU from its two main trust funds between 2018 and 2022, and has generally been on the rise since the Great Recession. In recent decades, the money has gone to construction and maintenance of the institution’s infrastructure, like its Biomedical and Health Sciences building, and the PACCAR Clean Technology Building — a research center focused on innovating wood products and sustainable design.

That revenue may look small in comparison to WSU’s $1.2 billion dollar endowment, but it has added up over time. From statehood in 1889 to 2022, timber sales on trust lands provided Washington State University with roughly $1 billion in revenue when Grist adjusted for inflation. But those figures are likely higher: Between 1971 and 1983, the State of Washington did not produce detailed records on trust land revenue as a cost-cutting measure.

Meanwhile, WSU students have demanded that the university divest from fossil fuel companies held in the endowment. But even if the board of regents agreed, any changes would likely not apply to the school’s state-controlled trust fund, which currently contains shares in ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, and at least two dozen other corporations in the oil and gas sector.

“Washington State University (WSU) is aware that our campuses are located on the homelands of Native peoples and that the institution receives financial benefit from trust lands,” said Weiler.

In states with trust lands, a reasonably comfortable buffer exists between beneficiaries, legislators, land managers, and investment boards, but that hasn’t always been the case. In Minnesota’s early days, state leaders founded the University of Minnesota while also making policy that would benefit the school, binding the state’s history of genocide with the institution.

Those actions still impact Indigenous peoples in the state today while providing steady revenue streams to the University.

Henry Sibley began to amass his fortune around 1834 after only a few years in the fur trade in the territory of what would become Minnesota, rising to the role of regional manager of the American Fur Company at just 23. But even then, the industry was on the decline — wild game had been over-hunted and competition was fierce. Sibley responded by diversifying his activities. He moved into timber, making exclusive agreements with the Ojibwe to log along the Snake and Upper St. Croix rivers.

His years in “wild Indian country” were paying off: Sibley knew the land, waterways, and resources of the Great Lakes region, and he knew the people, even marrying Tahshinaohindaway, also known as Red Blanket Woman, in 1840 — a Mdewakanton Dakota woman from Black Dog Village in what is now southern Minneapolis.

Sibley was a major figure in a number of treaty negotiations, aiding the U.S. in its western expansion, opening what is now Minnesota to settlement by removing tribes. In 1848, he became the first congressional delegate for the Wisconsin Territory, which covered much of present-day Minnesota, and eventually, Minnesota’s first governor.

But he was also a founding regent of the University of Minnesota — using his personal, political, and industry knowledge of the region to choose federal, state, and private lands for the university. Sibley and other regents used the institution as a shell corporation to speculate and move money between companies they held shares in.

In 1851, Sibley helped introduce land-grant legislation for the purpose of a territorial university, and just three days after Congress passed the bill, Minnesota’s territorial leaders established the University of Minnesota. With an eye on statehood, leaders knew more land would be granted for higher education, but first the land had to be made available.

That same year, with the help of then-territorial governor and fellow university regent Alexander Ramsey, the Dakota signed the Treaty of Traverse De Sioux, a land cession that created almost half of the state of Minnesota, and, taken with other cessions, would later net the University nearly 187,000 acres of land — an area roughly the size of Tucson.

Among the many clauses in the treaty was payment: $1.4 million would be given to the Dakota, but only after expenses. Ramsey deducted $35,000 for a handling fee, about $1.4 million in today’s dollars. After agencies and politicians had taken their cuts, the Dakota were promised only $350,000, but ultimately, only a few thousand arrived after federal agents delayed and withheld payments or substituted them for supplies that were never delivered.

The betrayal led to the Dakota War of 1862. “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state,” said Governor Ramsey. Sibley joined in the slaughter, leading an army of volunteers dedicated to the genocide of the Dakota people. At the end of the conflict, Ramsey ordered the mass execution of more than 300 Dakota men in December of 1862 — a number later reduced by then-president Abraham Lincoln to 39, and still the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

That grisly punctuation mark at the end of the war meant a windfall for the University of Minnesota, with new lands being opened through the state’s enabling act and another federal grant that had just been passed: the Morrill Act. Within weeks of the mass execution, the university was reaping benefits thanks to the political, and military, power of Sibley and the board of regents.

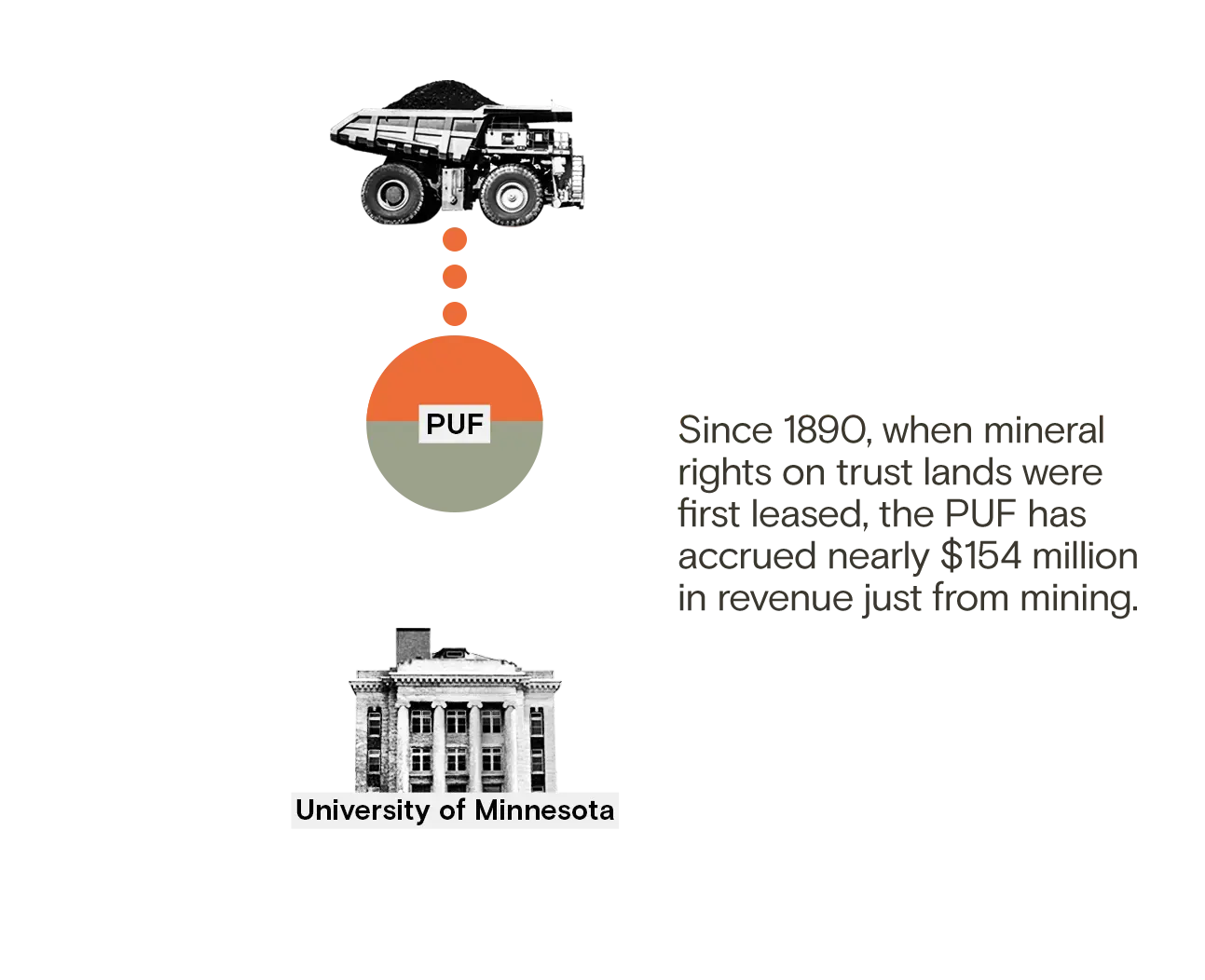

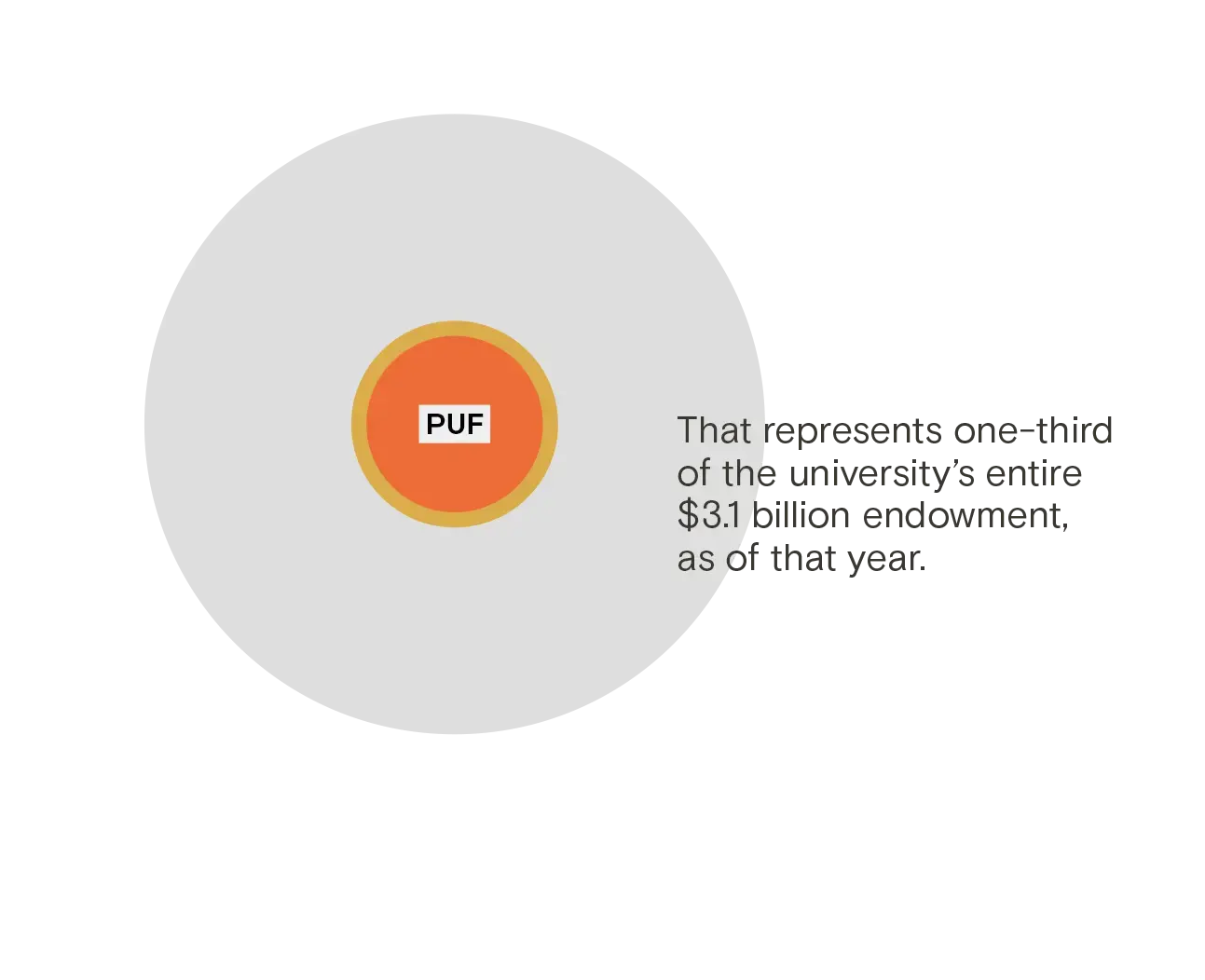

Between 2018 and 2022, those lands produced more than $17 million in revenue, primarily through leases for the mining of iron and taconite, a low-grade iron ore used by the steel industry. But like other states that rely on investment funds and trusts to generate additional income, those royalties are only the first step in the institution’s financial investments.

Today, Sibley, Ramsey, and other regents are still honored. Their names adorn parks, counties, and streets, their homes memorialized for future generations. While there have been efforts to remove their names from schools and parks, Minnesota, its institutions, and many of its citizens continue to benefit from their actions.

The iron and taconite mines that owe their success to the work of these men have left lasting visual blight, water contamination from historic mine tailings, and elevated rates of mesothelioma among taconite workers in Minnesota. The 1863 federal law that authorized the removal of Indigenous peoples from the region is still on the books today and has never been overturned.

Less than half of the universities featured in this story responded to requests for comment, and the National Association of State Trust Lands, the nonprofit consortium that represents trust land agencies and administrators, declined to comment. Those that did, however, highlighted the steps they were making to engage with Indigenous students and communities.

Still, investments in Indigenous communities are slow coming. Of the universities that responded to our requests, those that directly referenced how trust lands were used maintained they had no control over how they profited from the land.

And they’re correct, to some degree: States managing assets for land-grants have fiduciary, and legal, obligations to act in the institution’s best interests.

But that could give land-grant universities a right to ask why maximizing returns doesn’t factor in the value of righting past wrongs or the costs of climate change.

“We can know very well that these things are happening and that we’re part of the problem, but our desire for continuity and certainty and security override that knowledge,” said Sharon Stein of the University of British Columbia.

That knowledge, Stein added, is easily eclipsed by investments in colonialism that obscure university complicity and dismiss that change is possible.

Though it’s a complicated and arduous process changing laws and working with state agencies, universities regularly do it. In 2022, the 14 land-grant universities profiled in this story spent a combined $4.6 million on lobbying on issues ranging from agriculture to defense. All lobbied to influence the federal budget and appropriations.

But even if those high-level actions are taken, it’s not clear how it will make a difference to people like Alina Sierra in Tucson, who faces a rocky financial future after her departure from the University of Arizona.

In 2022, a national study on college affordability found that nearly 40 percent of Native students accrued more than $10,000 in college debt, with some accumulating more than $100,000 in loans. Sierra is still in debt to UArizona for more than $6,000.

“I think that being on O’odham land, they should give back, because it’s stolen land,” said Sierra. “They should put more into helping us.”

In January, Sierra enrolled as a full-time student at Tohono O’odham Community College in Sells, Arizona — a tribal university on her homelands. The full cost of attendance, from tuition to fees to books, is free.

The college receives no benefits from state trust lands.

CREDITS

This story was reported and written by Tristan Ahtone, Robert Lee, Amanda Tachine, An Garagiola, and Audrianna Goodwin. Data reporting was done by Maria Parazo Rose and Clayton Aldern, with additional data analysis and visualization by Marcelle Bonterre and Parker Ziegler. Margaret Pearce provided guidance and oversight.

Original photography for this project was done by Eliseu Cavalcante and Bean Yazzie. Parker Ziegler handled design and development. Teresa Chin supervised art direction. Marty Two Bulls Jr. and Mia Torres provided illustration. Megan Merrigan, Justin Ray, and Mignon Khargie handled promotion. Rachel Glickhouse coordinated partnerships.

This project was edited by Katherine Lanpher and Katherine Bagley. Jaime Buerger managed production. Angely Mercado did fact-checking, and Annie Fu fact-checked the project’s data.

Special thanks to Teresa Miguel-Stearns, Jon Parmenter, Susan Shain, and Tushar Khurana for their additional research contributions. We would also like to thank the many state officials who helped to ensure we acquired the most recent and accurate information for this story. This story was made possible in part by the Pulitzer Center, the Data-Driven Reporting Project, and the Bay & Paul Foundation.

The Misplaced Trust team acknowledges the Tohono O’odham, Pascua Yaqui, dxʷdəwʔabš, Suquamish, Muckleshoot, puyaləpabš, Tulalip, Muwekma Ohlone, Lisjan, Tongva, Kizh, Dakota, Bodwéwadmi, Quinnipiac, Monongahela, Shawnee, Lenape, Erie, Osage, Akimel O’odham, Piipaash, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, Diné, Kanienʼkehá:ka, Muh-he-con-ne-ok, Pαnawάhpskewi, and Mvskoke peoples, on whose homelands this story was created.