For decades, musical theatre has been used to highlight important social issues. "Cabaret" discussed the Holocaust. Many Rogers and Hammerstein musicals raised questions about racial tension. And today, "Dear Evan Hansen," a musical written by Benj Pasek, Justin Paul, and Steven Levenson, is sparking conversations about mental illness.

"Dear Evan Hansen" is the story of Evan Hansen, a teenager who struggles with social anxiety, only to have his problems amplified by modern society’s reliance on social media. When his classmate dies, and a letter of Evan’s is found, Evan slowly spins out of control as he works to find connection and a sense of belonging.

The show has had tremendous success on Broadway. It was nominated for nine Tony Awards in 2017, and won six of them, including Best Musical and Best Actor. "Dear Evan Hansen" has also recouped its initial financial investment of $9.5 million dollars in eight and a half months on Broadway–an astounding feat in a market where even financially successful shows take an average of two years to recoup.

The show’s success has prompted families, schools, and community organizations to start talking about mental illness. It has also prompted other composers and producers to move forward with their own works focused on mental illness. All of this has prompted some artists and critics to speculate that audiences are ready to see pieces of theatre that reflect the struggles they face in their own lives.

“Some people think of the popular theatre, which these days is often the musical theatre, as a kind of silly, easy swallow pill,” says Jesse Green, co-chief theatre critic at The New York Times. “In fact, it’s part of the ecosystem of change, one of the most important parts; because that’s where these subjects start to reach the largest number of people. You need the culture to echo the ideas that our geniuses are trying to put out there. One voice is not enough; you need a chorus.”

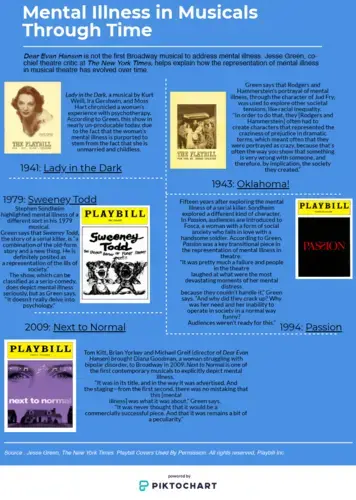

In many ways, the phenomenon of musicals addressing mental illness has been brewing for years. As early as 1941’s "Lady in the Dark," mental illness has been explored on the musical stage (see infographic below).

But it wasn’t until 2009 that Broadway musicals began depicting mental illness in an explicit way. "Next to Normal" told the story of Diana Goodman, a mother struggling to cope with her bipolar disorder. The show explored more than just the symptoms of her mental illness; it also explored her relationships, how her illness impacted her family, and how she dealt with psychiatric treatment.

"Next to Normal" garnered critical acclaim, Tony nominations and wins, and recouped its initial financial investment–no easy feat in an industry where close to 80 percent of shows are financial failures.

"Dear Evan Hansen" debuted on Broadway about seven years later. After finding inspiration from an incident that occurred during Benj Pasek’s time in high school, Pasek and Paul, along with book writer Steven Levenson and producer Stacey Mindich, were able to take "Dear Evan Hansen" from an idea to a Tony Award-winning musical.

Now, on the heels of the success of "Dear Evan Hansen," some composers believe there is new a market for their shows that address mental illness. Drew Gasparini, for instance, along with his writing partner Alex Brightman, is in the midst of developing Ned Vizzini’s novel, "It’s Kind of a Funny Story," into a new musical.

"It’s Kind of a Funny Story" is based on Vizzini’s own battle with mental illness. It is the story of Craig Gilner, a high school student who is struggling with depression. After experiencing suicidal thoughts, Craig checks himself into a psychiatric hospital where he meets a host of characters who are each facing their own challenges.

For Gasparini, the project has deep roots.

“Right before we started writing, I was going through my own bouts of hardcore depression. I’ve kind of been up and down my whole life with it. I don’t think I’ve ever tackled the problem head on,” Gasparini says.

He discovered Vizzini’s work soon after the NBC musical drama, "Smash," for which he had been writing, was cancelled in 2013. Experiencing what he calls a “low-low,” Gasparini turned to the internet, where he wrote a blog post titled "Choose to Live," which detailed his own struggle with mental illness. Soon after the publication of his essay, Gasparini found Vizzini’s work when he and Brightman were approached by Universal to develop a film from the Universal catalog into a musical. Vizzini had taken his own life in 2014.

Musicals, especially when the end goal is Broadway, can take up to a decade to develop. "It’s Kind of a Funny Story" is still in the early stages of development but had a concert staging in March of 2017 at 54 Below, a New York City supper club. And while fans are eager for a Broadway premiere (just check Twitter or Tumblr), Gasparini acknowledges that a full staging is far in the future.

However, as the show develops, Gasparini and Brightman have already partnered with a young actor who is ready to take on the role of Craig Gilner: Colton Ryan, who was a stand-by at "Dear Evan Hansen" for the better part of 2017.

Both Ryan and Gasparini, though, are quick to shoot down suggestions that "It’s Kind of a Funny Story" is simply another story of a young man struggling with mental illness.

“Every character has to be different,” Ryan says. “Just like the nuance of mental illness, these young men cannot be lumped together as the same just because they struggle with depression.”

Gasparini notes that while shows like "Next to Normal" and "Dear Evan Hansen" are creating a market for more musicals addressing topics around mental illness, the genre is by definition more expansive.

“I don’t think mental illness means depression or suicidal every time. Mental illness is going to become this new subgenre, so other subjects in mental illness can be tackled on the musical stage. Musicals aren’t what they were. We have a stage, we have a platform, let’s use it. We’re in a weird, scary time in the world, and I think now is the time to stop being safe with theatre,” Gasparini says.

Gasparini also acknowledges that as this market expands, there needs to be a wider and more diverse representation of mental illness in musical theatre.

“I would like to see more female led shows. We all understand mental illness, that’s a universal platform. But I don’t think the story hits the same for everyone if it’s a boy every time,” he says.

"It’s Kind of a Funny Story" is by no means the only show about mental illness currently in development.

"Afterwords," "Darling Grenadine," and "Sam’s Room" are each new musicals exploring different themes of mental illness. None of these shows have been written in response to "Dear Evan Hansen," according to their creative teams, but the composers and writers acknowledge that "Dear Evan Hansen" is creating an environment in which their shows can find success.

While Daniel Zaitchik, writer and composer of "Darling Grenadine," acknowledges that mental illness is a theme explored in the show, he insists it’s not the center.

“A person’s life ultimately is not about whatever is ailing them, it [the ailment] just gets in the way,” he says. “I wanted to write something that just explored how this problem [mental illness] not only affects [the character], but also the people around him. I gave equal weight and time to the people who are having relationships with him because that’s what’s relatable.”

Relatability is also something Zoe Sarnak and Emily Kaczmarek are striving to do with their musical, "Afterwords." Sarnak and Kaczmarek point out the diagnosis of mental illness in the show is intentionally vague, in an effort to allow the audience to connect through their own personal experiences.

“We talk about ‘representing without pathologizing,’” Sarnak says. “What does it mean to deal with the fact that the map of the world includes many powerful and wonderful and nuanced people who have various degrees of relationship with mental illness in their life, without it being the show about fill-in-the-blank mental illness.”

As Drew Gasparini points out, diversity in the kinds of mental illnesses depicted is also important.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, autism spectrum disorder and other non-verbal learning disorders, are classified as mental illnesses. Representing the stories of this community is a niche Dale Sampson and Caitlin Bell, one half of the creative team, hope to fill with the musical "Sam’s Room."

In "Sam’s Room," Sam, a young non-verbal man with special needs, struggles to communicate with the world around him. But through a superstar alter ego, Sam learns how to connect with those in his life.

Bell hopes that "Sam’s Room" will have an impact on not only the special needs community, but the wider world in general.

“I think any and all pieces that are written about mental illness, or special needs, [are] just going to add on to this community of people who are speaking about it, which will then hopefully lead to more research, which will then hopefully lead to more understanding. Art is one of the best tools for social change,” Bell says.

Search for "Dear Evan Hansen" on social media platforms and there are many posts of people connecting with each other over their shared experience with the show. Some will discuss their own battles with mental illness, while others may discuss how they can see themselves in the characters.

Dr. Nisha Sajnani, director of the drama therapy program at NYU, emphasizes that the benefit of a show like "Dear Evan Hansen" comes from a process known as “witnessing,” in which theatrical productions can provide comfort to those who are struggling. As a core process of drama therapy, witnessing involves bearing witness to a particular story in a group setting. This can be as traditional as partaking in a group therapy session and sharing stories, or more informal, like sitting in the Music Box Theatre and watching "Dear Evan Hansen."

Dr. Sajnani says that knowing “you are not alone,” a lyric from the first act finale of "Dear Evan Hansen," is a key part of this witnessing.

“'Dear Evan Hansen' is taking that message that we try to convey in group therapy, and bringing it into a public sphere, where thousands can benefit at one time. There is great potential for collective relief,” says Dr. Sajnani

As mental illness is discussed in a more open forum, both onstage and in social media, some mental health advocates are wondering if this does more harm than good.

Dr. Sajnani cautions that people need to determine if they are able to see a show like "Dear Evan Hansen."

“People will assess for themselves if this is something they can encounter. That’s really critical because the theatre shouldn’t be a place where one is forced to witness something they didn’t choose to witness,” she says.

Sajnani says that it is important for theatre-goers to have appropriate “aesthetic distance;” that is enough distance so that they can feel and think and be able to reflect on the experience.

And the way the cultural conversation around mental illness is changing, could be helping to make it easier for people to open up to seeing mental illness represented on stage. Dr. Victor Schwartz, chief medical officer at the JED Foundation, has seen how representation of mental health and mental illness has changed over the past few years.

“I think mental health has been more and more discovered; there are more celebrities talking about their mental health. The fact that performers and some sports figures have come out and started to openly talk about suicide and mental health has clearly opened up the issue,” says Dr. Schwartz.

There are some who are still skeptical about the staying power of the trend. Green, the Times critic, says the box office dominance of "Dear Evan Hansen" may limit other shows from finding their way to Broadway.

“I think it may be a feeling that there’s not a market for one [a musical depicting mental illness]. "Dear Evan Hansen" is not going anywhere. The big test of that happened when Ben Platt left the show, and it’s still selling as well as it did before.”

But other creators are not dissuaded.

“People want to see their lives reflected on stage and I think the success of "Dear Evan Hansen" and other shows like that are proving that. It’s an exciting time for musical theatre, especially when we start getting deeper,” Zaitchik says.

Kaczmarek also strongly believes that there is room for many musicals that touch on mental illness.

“I think that the idea that there can only be one show that deals with a capital letter topic, and then it becomes passé; I think you could write a hundred musicals that deal with mental illness in some way and I think that each of them–provided they were good shows–would still be necessary because it’s [mental illness] something that is so pervasive, and it’s so common, and it’s unique.”