But since police continue to be first on scene to most mental health-related 911 calls, the local 24/7 support line offers a way to reach mental health professionals sooner

In the summer of 2022, Marshall was in crisis. Years of living with undiagnosed clinical depression and drinking had left the longtime resident of Eagle County feeling trapped and unable to see a way out.

In a resort community where the lifestyle of wealthy tourists and second-home owners is supported by low-wage service workers, Marshall said he was constantly looking for an escape.

“I was just lost and feeling numb,” said Marshall, who asked to use only his first name to protect his privacy. “I felt trapped in my own body and trapped in a small town, and I started isolating myself and drinking more.”

He messaged a close friend, Kirby Lemon, about the despair he was feeling, and she began to fear for his safety. Without access to his apartment to check on him, Lemon felt she had no choice but to call 911.

An officer from the Eagle Police Department responded and requested assistance from Your Hope Center, a local nonprofit that deploys mental health clinicians to respond to crisis situations alongside police officers and paramedics.

Marshall’s memories from that night come back in flashes. But one thing he does remember is that while a police officer came in to make sure he was safe, the officer let the paramedics and clinician take over once they arrived. Everyone on scene made it their priority to get him the mental health support he needed, he said.

“I think I was lucky in that I had an experience where everything went exactly the way it’s supposed to go,” Lemon said.

This is not always the case. More than five years after law enforcement officers in Eagle County began the co-response program, crisis clinicians can only respond to a 911 call at the request of police, rather than being dispatched alongside or instead of police.

In addition, the public data used to report to the state about the program’s progress is incomplete and unreliable, according to Your Hope Center and police leadership.

The more reliable data is collected by Your Hope Center, they say, which shows that although the co-response program helps avoid arrests and costly hospitalizations, the number of times crisis clinicians respond on scene is low relative to a similar program in neighboring Summit County.

The program also faces linguistic and cultural challenges in serving local Latino residents, who make up 30% of the population.

Interpretation services “help break down the barrier a little bit, but it’s still never going to be the same as if you were talking with somebody that understands your language and your culture,” said Michelle Dibos, the former community engagement director for Vail Health Behavioral Health. “It’s different when you are able to receive services in the language of your heart.”

The Eagle Valley’s investment in mental health

Regionally, the Eagle River Valley has been at the forefront of investing in mental health as Vail Health prepares to open the county’s first inpatient behavioral health hospital. The push to dispatch clinicians on mental health-related 911 calls has moved more slowly, despite Your Hope Center receiving $80,000 in taxpayer funding annually since 2019 in addition to private dollars, according to county budget documents.

Another $20,000 from the county’s annual marijuana tax revenue goes to Aspen Hope Center, which helped start the co-response program in western Eagle County in 2018.

From 2021 to 2023, Your Hope Center clinicians responded in person with police or paramedics 448 times and 946 times on their own, according to the center’s records.

But despite serving a considerably smaller population, co-response teams in neighboring Summit County served nearly the same number of people (1,267 calls) in the first 10 months of 2023 alone, connecting people to follow-up mental health care along the way, according to data tracked by the Summit County Sheriff’s Office. There was no force used and no arrests made by deputies on any of these calls, but the teams do not handle calls that involve reports of serious crimes.

When clinicians respond to calls alongside police or paramedics in Eagle County, 80% of people in crisis are supported with a safety plan and mental health care within the community, according to data from Eagle County Paramedic Services. People in crisis that receive a traditional response from police and paramedics are more likely to be jailed or transported to the emergency department, which can be expensive — especially for the uninsured.

Occasionally, local police use force against people in crisis, placing them in handcuffs or other restraints, according to use-of-force reports reviewed by the Vail Daily and MindSite News. The Eagle County jail is no longer receiving crisis support from Your Hope Center due to a change in the nonprofit’s insurance coverage and lacks the resources necessary to meet the mental health needs of the county’s most vulnerable residents, leaving them in what one expert called a “revolving door” of crisis, criminalization and trauma.

A brief history of mental health care in Eagle County

In 2017, Eagle County reported a rate of 23 suicides per 100,000 residents — higher than the statewide rate of about 20 per 100,000 people and significantly higher than the national rate of about 13.

Eagle County lacked mental health infrastructure, like many rural communities in Colorado and other Mountain West states that consistently report some of the highest suicide rates in the nation. Waiting for months to see a provider and driving two or more hours to Denver or Grand Junction for in-patient care was — and, to some extent, still is — the norm for people seeking mental health care.

Eagle County voters approved a local marijuana tax in 2017 to fund mental health programs. The fund, which is overseen by an advisory committee of leaders from first response agencies, Vail Health and local nonprofits, brings in about $800,000 annually, according to numbers provided by Vail Health.

In July of 2019, Vail Health formed what is now known as Vail Health Behavioral Health. Since then, it has invested more than $26 million in improving behavioral health services in the valley and secured over $20 million in state funding.

Eagle County’s co-response program began in the fall of 2018, and Your Hope Center has been sending out clinicians 24 hours a day, seven days a week since 2021 when it became its own nonprofit based out of Eagle. The local marijuana sales tax funds help support the program but, today, Your Hope Center is largely supported by state funding that flows through Vail Health Behavioral Health.

The response: who’s first on scene

When Lemon called 911 for Marshall that night in 2022, she had just started working for the local suicide awareness nonprofit SpeakUp ReachOut, she said. After serving as training and events coordinator for about two years, she now knows she can call 988 or Your Hope Center’s 24/7 support line at (970) 306-4673 rather than calling 911.

This is a way of getting in touch with a mental health professional earlier in the process. Your Hope Center clinicians regularly respond without police when calls come into the support line. They use their clinical knowledge of mental illness to assess the situation and summon police if someone on scene is armed or actively trying to hurt themselves or others, Clinical Director Teresa Haynes said.

One challenge in responding to mental health-related 911 calls, on the other hand, is identifying them as such without this specialized knowledge, said Alex Pollinger, a dispatcher who answers calls for the Vail Public Safety Communications Center. Sometimes a call is categorized as a “disturbance” or an intoxicated person based on the initial information given and isn’t determined to be a mental health crisis until first responders are on scene.

Since dispatchers can’t be certain, the Vail Public Safety Communications Center developed a policy to automatically dispatch police first, said the center’s director Marc Wentworth. Dispatchers cannot send clinicians at the same time as police or at all, without authorization from police.

Police rely on the 40-hour mental health de-escalation training offered by CIT International, which most Eagle County officers have taken, to determine when to call for a co-response. If on scene, they may be aided by “community paramedics” that receive more behavioral health training than other Eagle County Paramedics, Community Health Manager Alice Harvey said.

"Should we be responding to mental health calls? No, we shouldn’t. It’s not our job. We’re not mental health practitioners, we’re not clinicians. But we are the catch-all for society."

—Avon Police Chief Greg Daly

In an October interview, Wentworth said he was not sure why clinicians are not dispatched at the same time as police, when appropriate, to speed up the process. Clinicians can take upward of 45 minutes to arrive on scene as they do not have radios, lights or sirens like first responders do, Haynes said.

“It probably feels like an extremely long time for the person in a mental health crisis,” Pollinger said. “As much as I admire our police force, and I really appreciate all our law enforcement agencies, especially in today’s climate regarding law enforcement, it’s hard for law enforcement to de-escalate a situation.”

Avon Police Chief Greg Daly, Vail Police Chief Ryan Kenney and Eagle County Sheriff James van Beek all expressed hopes that the co-response program might outgrow the need for law enforcement in some capacity. The Eagle Police Department did not respond to requests for an in-person interview, but later expressed its support for the co-response program in an emailed statement.

“Should we be responding to mental health calls? No, we shouldn’t. It’s not our job. We’re not mental health practitioners, we’re not clinicians,” Daly said. “But we are the catch-all for society.”

Mental health professionals and researchers say the presence of a uniformed officer can escalate a mental health crisis if the person in crisis has a history of trauma or distrust toward police from their own lived or vicarious experience with police violence in the United States.

With Summit County’s “SMART” program, co-response teams listen in to police radio traffic and dispatch themselves when they hear a call they determine to be mental health related, Sheriff Jaime FitzSimons said. First responders and community organizations can also request an assist.

The teams consist of plainly clothed sheriff’s deputies along with clinicians in an attempt to reduce the trauma that seeing a uniformed officer can evoke for some people, FitzSimons said.

“I think it defeats the purpose,” FitzSimons said. “We’ve seen people in crisis and when they see a uniform or a marked car, they’re no longer focused on whatever the clinician is trying to tell them. They’re now focused on, ‘Am I gonna get arrested? What does this mean?'”

However, clinicians are always accompanied by a deputy and the program is housed under the Sheriff’s Office.

Haynes said she understands the “push in the field of mental health to further minimize the involvement of law enforcement,” but added that she trusts Eagle County police as partners.

“I would not say that that’s a hope,” Haynes said. “I hope that we work ourselves out of a job. I hope that people aren’t suicidal anymore. But I don’t see that happening and I don’t see that there will ever not be a need, at least on some responses, to include law enforcement.”

But Your Hope Center has talked with police, paramedics and dispatchers about how to get clinicians on scene sooner. Staff have spoken about trialing a new model — having dispatchers enter certain keywords into 911 call notes to trigger the deployment of mental health clinicians at the same time as police, Haynes said.

The program has already made a similar adjustment for people with acute mental health issues who call often and already have safety plans in place with Your Hope Center, Pollinger said. In these cases, clinicians are notified right away.

These are challenges faced by co-response teams across the country, said Regina Huerter, who helped produce a 2020 study on national co-response models. They can lead to crisis clinicians being sent out late or not at all, and affect the ability to collect data to accurately assess the effectiveness of these programs.

The lack of clear data

When collecting data on the co-response program, Rebecca Pacheco, a Vail dispatcher and records technician, focuses on seven call types that she and Your Hope Center identified as having the highest likelihood of being mental health-related. This includes calls explicitly labelled as mental health and suicide calls, as well as welfare checks, domestic issues, intoxicated parties, assaults and disturbances. Pacheco said all seven are classified as “mental health events” when reporting the data to the state.

Pacheco’s data showed that law enforcement contacted Your Hope Center for a co-response 223 times between Jan. 1, 2021 and Dec. 21, 2023, across these seven call types.

An analysis of just mental health and suicide calls showed that clinicians with the co-response program were only contacted in 13% of mental health and suicide calls made during the same roughly three-year period.

When asked about the 13% utilization rate, police chiefs said their officers often call for a co-response from their cell phones, rather than phoning it in through dispatch, which would not show up in the dispatch center’s data.

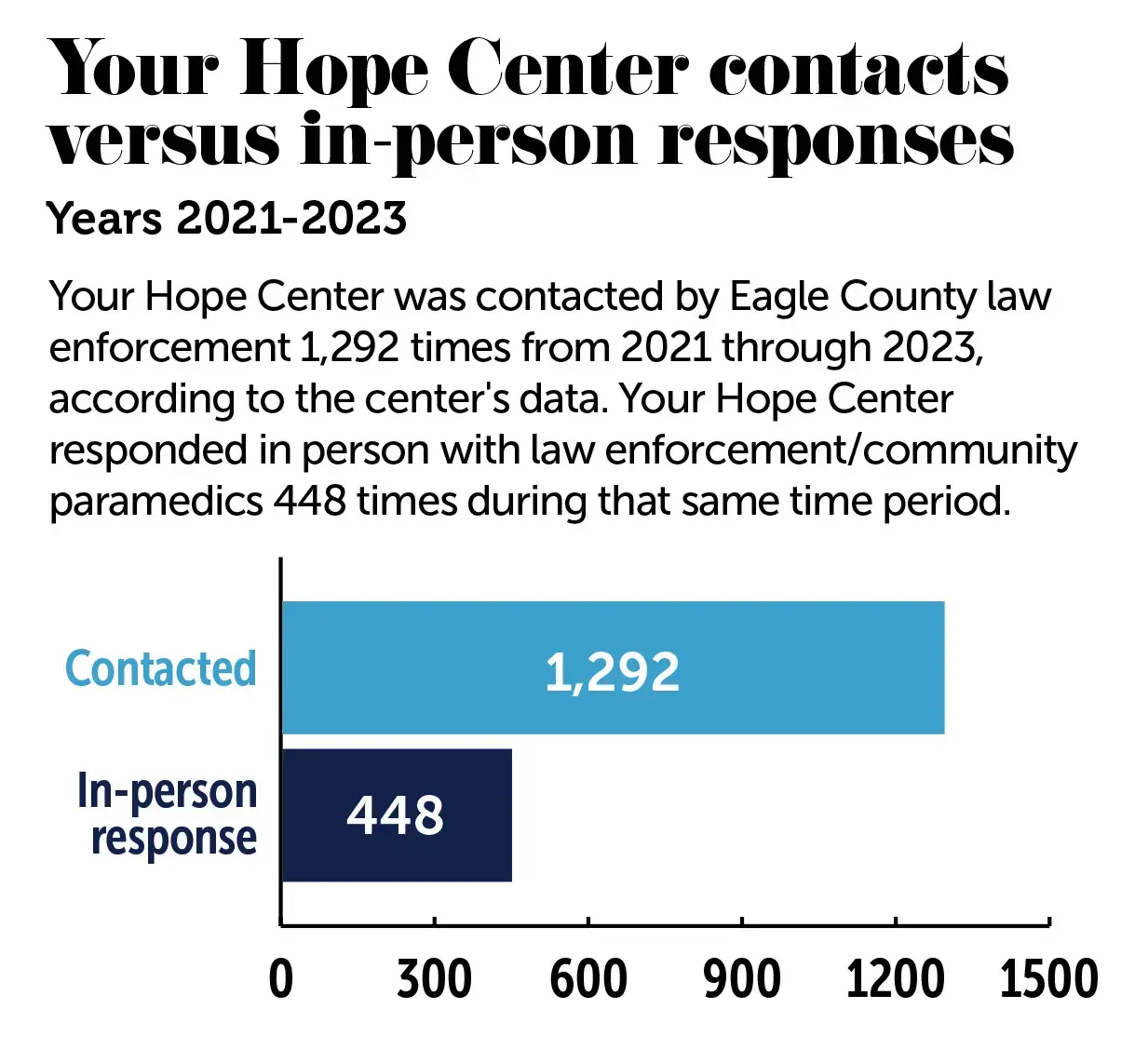

Chief Daly then ran a keyword search of countywide calls for service to try to produce data that captures these calls from cell phones. He found that the words “Hope Center” were mentioned 1,292 times from 2021 to 2023 across all call types.

This number, however, includes some duplicates, times when officers decided not to contact Your Hope Center and times when Your Hope Center requested assistance from police while responding to its support line, Daly said.

The “more concrete figure” is the data collected by Your Hope Center, he said, which shows that clinicians responded in person with law enforcement or paramedics 448 times over the course of three years – 128 times in 2021, 148 times in 2022 and 172 times in 2023.

Vail Police Chief Kenney said the 13% utilization rate — and the debate surrounding the county’s data — says more about the lack of a proper record management system among Eagle County law enforcement than anything else.

“If you’ve got crap in, you’re going to get crap out and we’ve got a lot of bad data in our current (records management system),” Kenney said. He’s trying to fix this.

Kenney estimated that his officers call for a co-response on “at least 75%” of mental health calls and that, if anything, they are over-utilizing the program.

“We want as soon as possible to get the right people there and to get this patient stabilized and to get ourselves out of that call,” he said.

The data from Daly’s keyword search and from Your Hope Center suggest that crisis clinicians respond in person about one out of every three times they are contacted for a co-response.

When they don’t respond in person, they talk to officers by phone, take a referral for crisis care or provide support to people in crisis via call or video call. Given their longer response times, clinicians often can provide support to more individuals using telehealth rather than responding in person, Haynes said.

The need for more culturally competent care

To better meet the needs of the community, Your Hope Center has increased its capacity to staff two crisis clinicians who work in 24-hour shifts — one on-duty and one on-call.

However, the organization does not have any bilingual crisis clinicians who speak Spanish and, instead, relies on the use of phone-in interpretation services. Latino residents make up about one third of the population in Eagle County and the majority of the school-aged population, according to the 2020 Census. Spanish speakers make up 18% of adult residents and 37% of kids ages 5-17.

The lack of culturally competent care for Latino residents is also a problem after the acute crisis is over, making it difficult to connect them to appropriate follow-up care in Eagle County, said Dibos, the former community engagement director for Vail Health Behavioral Health.

Benway said clinicians and staff would like to add bilingual, bicultural clinicians to the crisis team, but have struggled to recruit someone with that combination of skill sets.

Improving access to continued care

For Marshall, who was helped by the Eagle County co-response team in 2022, being diagnosed with depression and getting treatment made a big difference in his life. Still, he said he did not fully realize how challenging the road ahead would be.

In May of last year, Marshall experienced another mental health crisis and first responders were called on his behalf. Because of their previous interactions, Your Hope Center staff got involved, and he ended up getting treated at Highlands Behavioral Health and began his path toward sobriety.

Because he was surrounded by other people who were all coming back from “their lowest point,” he felt he could tell more of his story and things he was feeling to staff and fellow patients than he could his closest friends. “Everything’s just open and out there,” he said.

Going back home, he said his biggest worry was falling back into the “same feelings and habits” he was having before. When he was discharged, he realized he already had appointments set up for him with a psychiatrist, therapist and Your Hope Center clinician.

“I really was well taken care of — I wasn’t just dropped off back in my situation,” Marshall recalled. “I had people I could still talk to and that could help me along the way, like, two or three times a week.”

Your Hope Center works with community paramedics to treat people in their home environments whenever possible and make sure they have a plan to receive continued care, said Alice Harvey, a community health manager with Eagle County Paramedic Services.

This is particularly important for people with acute mental health issues who, without co-response, often cycle in and out of emergency rooms and become trapped in a “vicious cycle” of medical debt, inadequate treatment and homelessness, said Pollinger, the 911 dispatcher who formerly worked as an EMT.

“Historically, we’ve done a great job with acute crises, right? … But what we haven’t done is look at that baseline level of crisis,” said Haynes, the center’s clinical director. “What contributes to this person — in their makeup, their genetics, their coping skills, their life circumstances, their environment — What is it that keeps them continuing to bump up into that acute level of crisis?”

Haynes has assembled a team of clinicians, case managers and peer mentors designed to provide care and resource connection in a more individualized way based on the answers to these questions.

Since 2021, there has been a slow but steady decrease in involuntary commitment to behavioral health hospitals as well as the number of mental health evaluations performed at local emergency rooms, according to data from Your Hope Center. Haynes attributed these successes to the team, known as the community stabilization program, which provides daily support for people as they move from crisis to recovery.

For Marshall, this kind of follow-up care meant a lot to him as he transitioned out of in-patient and back into daily life.

“People don’t realize that when you’re really down and having a depressive episode, doing normal day-to-day tasks, like making appointments, and making quick phone calls and stuff can be really, really difficult,” he said. “And so just having that structured, like, ‘Here’s what you’re gonna go through’ — I don’t think I would have done that on my own.”

Funding for this story was provided by the Pulitzer Center and the Fund for Investigative Journalism.