TERRAT VILLAGE, Tanzania — For generations, the Maasai people have grazed their cattle and goats on Tanzania's savannas, moving freely from place to place in search of plants that the animals need to yield the milk and meat that are the mainstays of the Maasai diet.

Now, food security for the Maasai and others is threatened by tension over that land — where feuds are simmering over issues similar to those that divided cattle drivers and farmers in America's Old West.

With a rapidly growing population, Tanzania faces new demands for land dedicated to private uses. Planted crops and fences are claiming ground on the formerly open savanna. Developers come in search of wood, hunting grounds and other uses for the land.

Meanwhile, the government, under pressure to support development, is enforcing new restrictions on the pastoralists.

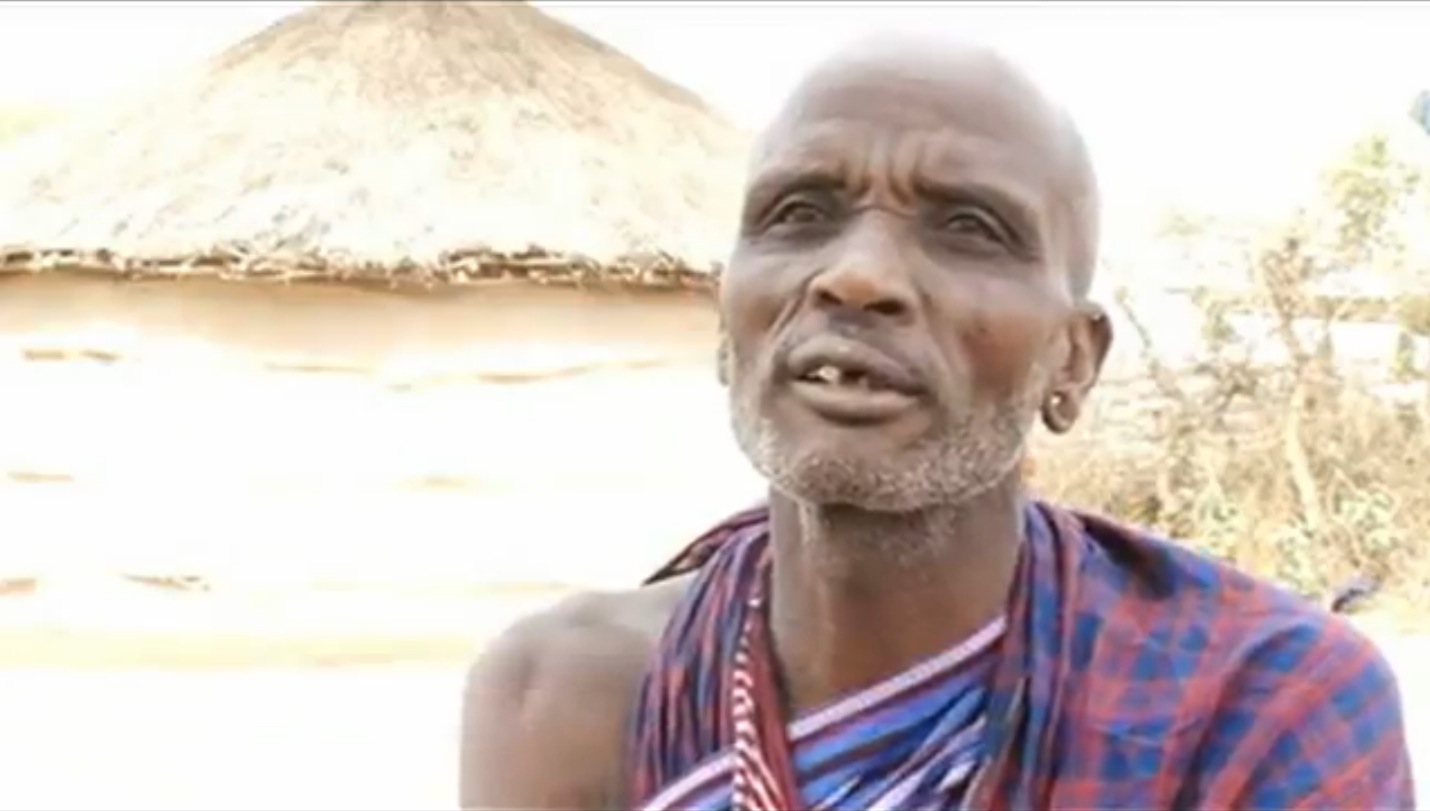

"Being a pastoralist is being in a daily struggle to feed animals so that they can feed you later," said Parmelo Ndiimu, a Maasai elder in this northern Tanzanian village.

On top of development pressure, Tanzania and other countries across Africa face worries over a future when climate change and other environmental problems could force disruptions in the old systems of producing food.

Tanzania gets two rainy seasons each year, a long one in the spring and a shorter one in the fall. During those wet seasons, the Maasai enjoy a relatively easy existence. Green pasture is readily available. Cows and goats can graze together near the villages, making it easy to care for the animals.

Drought is a different story. And drought has become a chronic condition in this part of Tanzania. Drought brings hunger and worry. Pastures dry up, and the Maasai herders must drive their livestock for miles looking for grazing land and water. While they are away, their families no longer get milk and meat from the animals.

So it is better for everyone — animals, herders and their families — if the Maasai can develop strategies for feeding their animals during dry spells.

The acacia tree, a common feature on the savanna landscape, can mitigate the impact of drought for goats. These trees develop seeds even when they are dry. Goats eat the seeds, draw nourishment from them and continue to give milk and meat to the Maasai. With acacia trees available, families can keep their goats near home.

This is one serious source of tension. The tree is in high demand for charcoal, which is used for cooking and heating in Tanzania's major cities.

Every day at least three acacia trees are lost near Terrat, said Ndiimu and other villagers. So Maasai pastoralists must go farther and farther in search of the trees.

In addition, the land available for goats to graze is shrinking in the face of demands for individual control of property.

Looronyo Saning'o, the village executive officer, said that the government must enforce its land use plan, which designates specific areas for specific uses.

One justification for the strict enforcement, he said, is "so we prevent any kind of conflict." For the Maasai, though, that policy spells a hungry future and the loss of traditions that have defined their people for as long as anyone in their villages can remember.

As a food source, Ndiimu said livestock stands for the Maasai's very existence.

"If we won't be able to feed our goats, we will not be able to feed our children," he said. "And we will be gone."

View the video that accompanies this article at the Des Moines Register online.