The Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forest reserves once blanketed the northeastern coast of Johor. Side by side, the reserves stretched 25 km long and 11 km wide. This year, the Jemaluang reserve would have been 98 years old, and Tenggaroh 70.

But six years ago, in December 2014, both forest reserves were excised, or degazetted, by the Johor state government. At 15,011 hectares, this is the largest one-time excision of forest reserves in Peninsular Malaysia since 2000.

The 2014 excision followed an earlier excision two years ago of 2,619 ha from Tenggaroh. This means that Jemaluang and Tenggaroh had lost a total of 17,630 ha of forest reserves.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund journalism covering underreported issues around the world. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

How big were the reserves really?

Some of the land was taken into private ownership. An undisclosed size is owned by the monarch of the state, Sultan Ibrahim Sultan Iskandar.

About 21% of the forests has been cleared for oil palm estates and a gold mine – all on land owned by Sultan Ibrahim.

Last year, Macaranga featured one of these forests – Jemaluang – in our Forest Files stories to illustrate how top-down decisions to excise and clear forest reserves could hurt the interests of local communities.

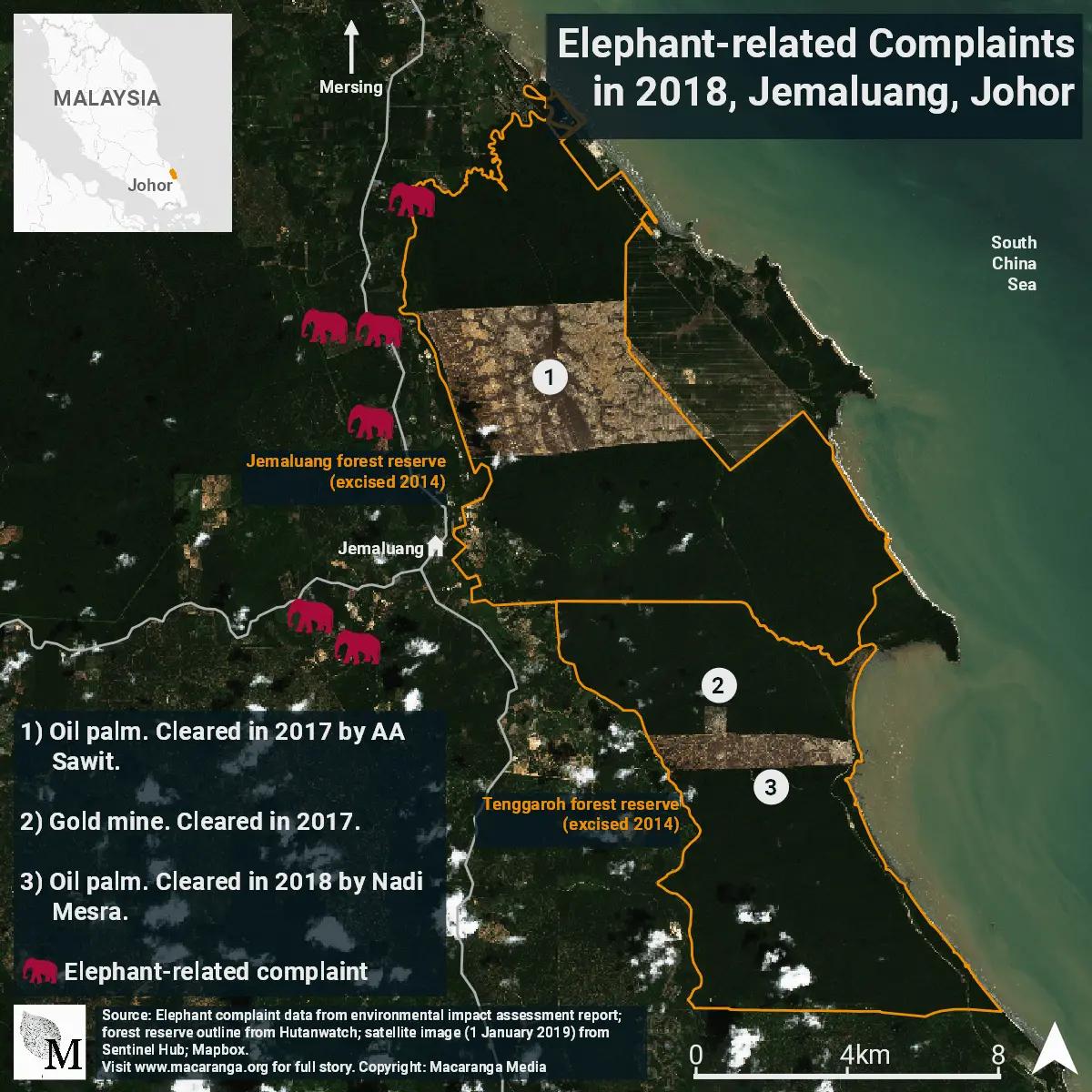

Jemaluang residents had been suffering economically from roaming elephants living in the adjacent forests, parts of which had been cleared. They had hoped that the government would rein in deforestation.

But a year since our visit, more of this forest and the adjacent Tenggaroh forest is expected to go. There are at least three proposed projects to convert another 24% of the forests into plantations and mines.

One by one, these projects will carve up and clear one of the last remaining intact coastal rainforests in Peninsular Malaysia. What has been the impact? If there were gains, who has reaped them?

A century of reserves transformed

The Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forest reserves were gazetted by the Johor state government on 1 October 1923 and 8 November 1951, respectively.

The reserves were no longer listed in the Johor Forestry Department annual reports for 2015–2019, which indicates they were completely excised by 2014. The gazette for Jemaluang forest reserve, 1923 (Courtesy of Sinar Project)

A few years later, the forest reserves were much transformed as developers worked on land belonging to Sultan Ibrahim. (See map below)

In November 2016, loggers first began with trees in the north. Satellite images show that the parcel of 2,190.49 ha (PTD 1814) was completely cleared by December 2018 and planted with oil palm.

The developer is AA Sawit Sdn Bhd, a company 51%-owned by Sultan Ibrahim, with his son Tunku Ismail Sultan Ibrahim being one of the two directors.

Then, in 2017, a 43 ha plot further south was cleared for a gold mine. And in June 2018, another company, Nadi Mesra Sdn Bhd, began felling a parcel of 2,125.17 ha (PTD 217) for oil palm. By August 2021, about 73% of this parcel has been logged bare.

More forest loss is imminent.

On 17 August, Nadi Mesra Sdn Bhd submitted an EIA report for a 2023.72 ha plantation project (at PTD 216) in the forest. This is their third submission for the project this year after two earlier ones were rejected.

In November, Nadi Mesra will file an EIA report for a separate 2245.3 ha plantation (at PTD 218), the EIA consultant involved told Macaranga.

A third proposal targets the gold veins that run under the forest. Southern Alliance Ltd, a Singapore-listed company, is partnering with Sultan Ibrahim to mine gold there.

Southern Alliance and Nadi Mesra are helmed by the same person – Pek Kok Sam, a Malaysian.

Macaranga reached out to the stakeholders involved. AA Sawit did not respond to interview requests. Nadi Mesra declined to comment, citing possible reprimand from the “landowner” (i.e., Sultan Ibrahim) if they do so.

Macaranga could not reach Sultan Ibrahim for comments. The Royal Press Office, which handles the Johor sultan’s official communications, did not respond to interview requests.

In the next three sections, we describe how logging, plantation, and mining projects in Jemaluang and Tenggaroh have affected and may affect the forests, animals and plants, the economy, and the community.

Forests

As more developers set upon the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests, one is prompted to ask if the gains outweigh the costs, and for whom?

The Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests are unique coastal dipterocarp and freshwater swamp forests, the Malaysian Nature Society tells Macaranga.

These forests “are very scarce in Peninsular Malaysia and mostly confined to the lowlands of the east coast.”

Such lowland coastal forests hold the highest biodiversity in Malaysia, says an ecologist who has been studying the region for two decades. He requested anonymity.

Because these forests are the easiest and most lucrative to log, Malaysia has very few of them left. “Johor still has quite a large patch and I feel that these are valuable and people should do more to protect them,” he says.

He adds that clearing the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests undermines the larger forest conservation efforts in Peninsular Malaysia.

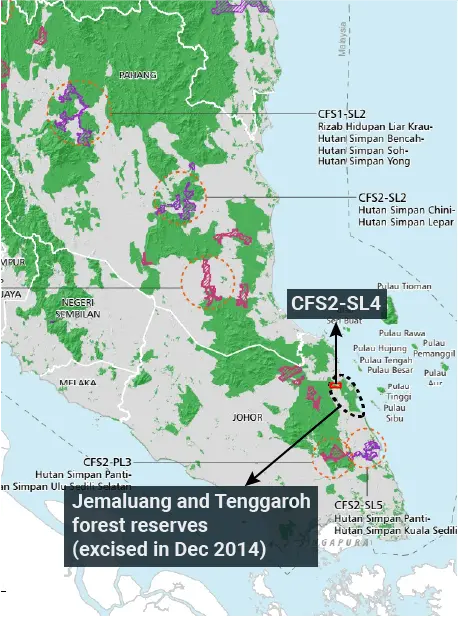

The Malaysian federal government has been working to establish the Central Forest Spine – a contiguous forest landscape from northern to southern Peninsular Malaysia.

The Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests were part of the southern clusters. A ‘secondary linkage’ (SL4 in image below) would connect Jemaluang and Tenggaroh to the main forests, and animals would thrive in a far bigger habitat.

But the development in the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests casts doubts on these roles in the Central Forest Spine.

The EIA report for the oil palm plantation in PTD 216 (Tenggaroh) stated that “the naturally forested area is isolated and disjunct, making the forest corridor disjointed. It is fragmented by plantation and infrastructure development.”

The Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources and the Forestry Department of Peninsular Malaysia did not respond to questions on this secondary linkage.

State governments tend to develop forested land that they say are already degraded and provide little timber or ecological services.

Were the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests degraded before they were excised?

EIA reports say forests were degraded

Golden Ecosystems Sdn Bhd, the EIA consultant for AA Sawit and Nadi Mesra, thought so. In its EIA reports, the consultant wrote that the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests were “not a healthy, productive forest” because it was “difficult to find mature timber species with girth(s of) more than 30–40 cm”.

A sawmill owner in nearby Kota Tinggi agrees. He has been buying timber from AA Sawit and Nadi Mesra’s plots, and most of the logs had smaller than 30 cm diameters. He requested anonymity.

He adds however that he only bought cheaper varieties of timber. He does not know the sizes or quantity of more expensive timber like cengal, kapur, or meranti in the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests.

The Johor state forestry department did not respond to questions about this matter.

Ample time to be a rich forest

However, other evidence suggests that even if the forests were not rich, they were far from poor.

According to Google Earth satellite images, small pockets of the forests were logged between 1991 and 2012. But most of the forests showed no signs of disturbance in the three decades since 1984.

By 2014 – the year they were excised – these forests should have harboured adequate timber for a new round of sustainable logging, according to estimates used in Peninsular Malaysia’s forestry practices.

Another way to assess the quality of the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests is to compare them to nearby forest reserves.

Official inventories of plots in nearby forest reserves found 2–3 large trees per hectare in 2018. These plots were deemed productive and lucrative enough to be logged sustainably.

Animals and Plants

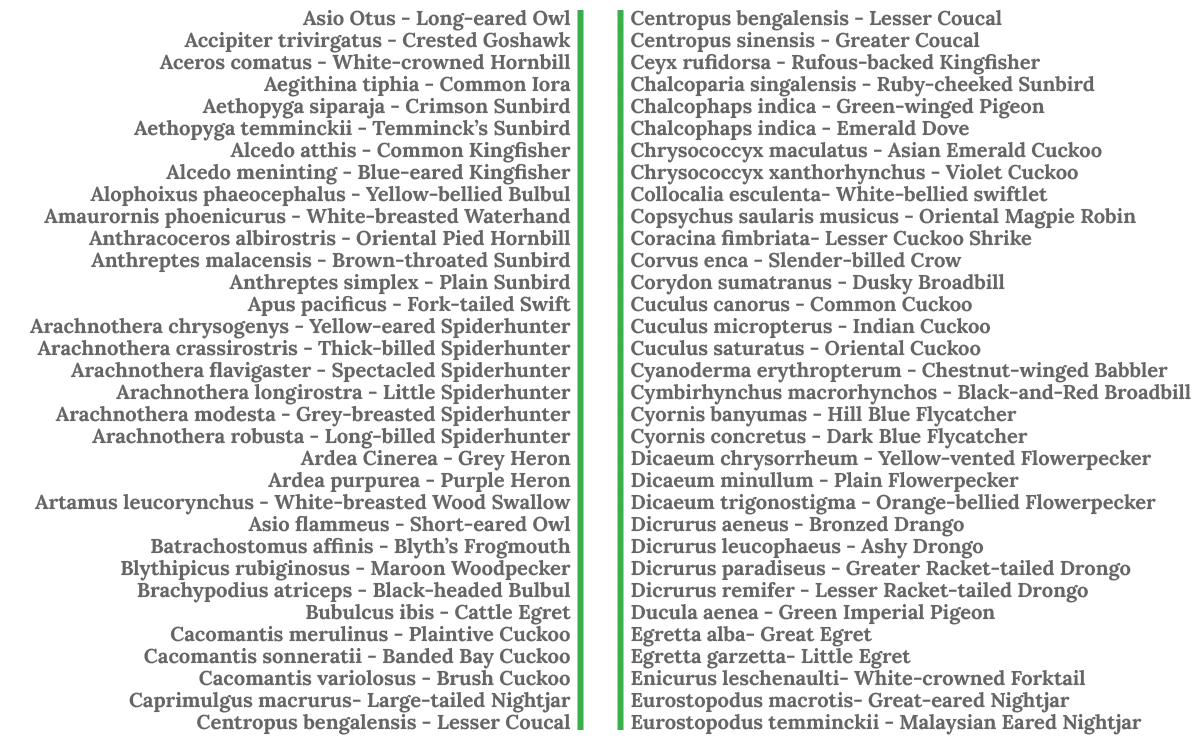

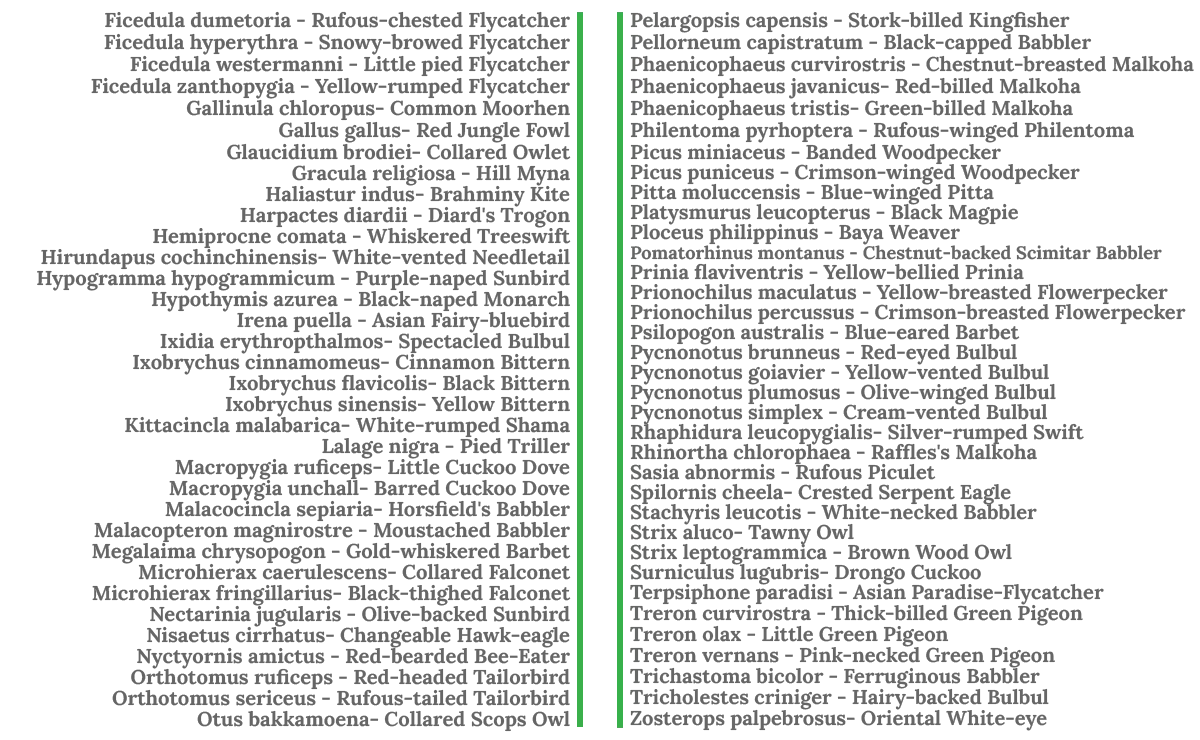

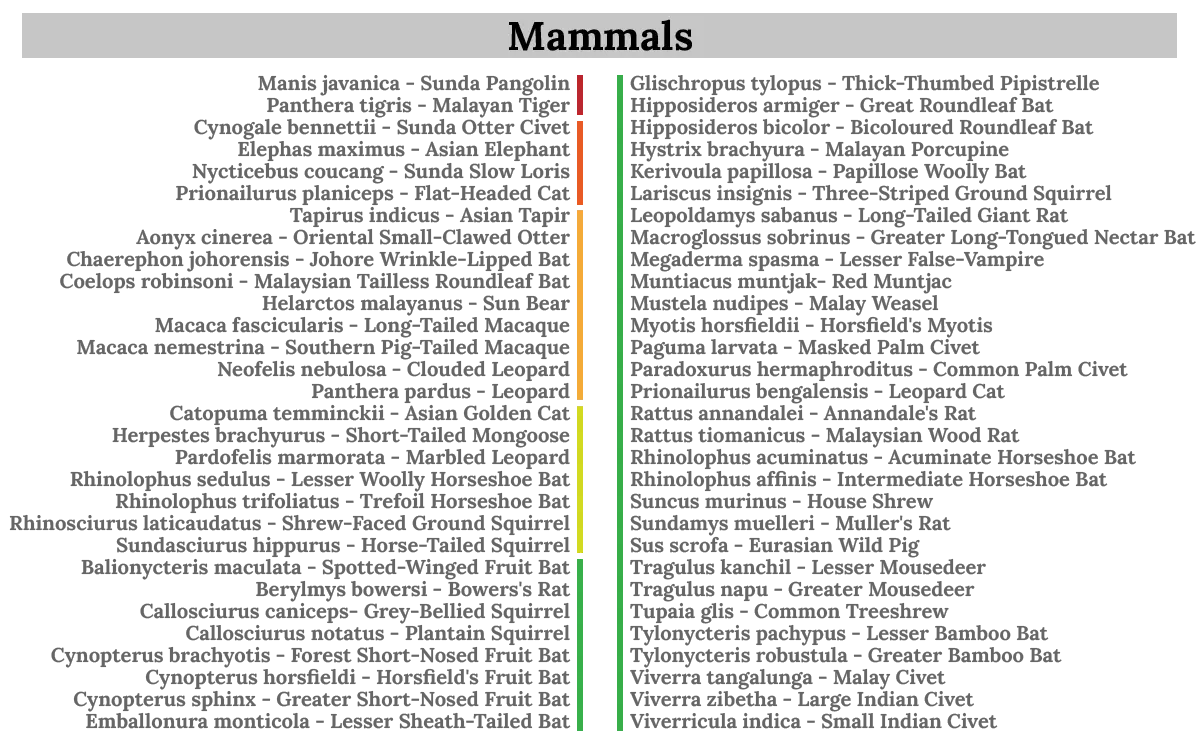

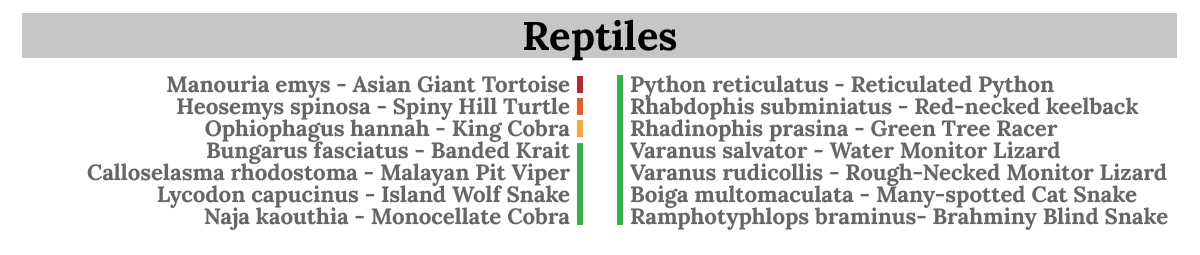

While the available evidence diverges on the quality of timber in the forests, it is clear that the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests support rich biodiversity.

Hundreds of plants and animal species are found or expected to be found in these forests, according to EIA reports. These include large animals like elephants, tigers, sun bears, and tapirs.

The EIA report listed 183 plant species in PTD 216 – the 2,024 ha plot, which Nadi Mesra wants to turn into a plantation. The report described this collection as “merely” 2.2% of vascular plants in Peninsular Malaysia.

But that statement underestimates the importance of that figure. Compared to its size as a proportion (0.035%) of total forest land in the Peninsula, PTD 216 actually carries 63-times its expected load of plant species.

One interesting highlight in the EIA report is the conservation needs for the Meranti telopok (Shorea peltata) tree. The species is endangered in Malaysia and critically endangered worldwide.

In Peninsular Malaysia, this species was actually once thought extinct but was rediscovered in northeastern Johor. Most trees were found in the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests.

Since 2010, habitat loss all over northeastern Johor has halved the area in the state where Meranti telopok can be found, according to the Malaysia Red List (2021) by the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM).

There have been reported efforts FRIM and the Forestry Department of Peninsular Malaysia to establish areas of High Conservation Value Forest in Tenggaroh to protect Meranti telopok.

Neither FRIM nor the forestry department responded to questions on conservation in the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests.

Another point of note in the EIA report is that PTD 216 was also part of the Endau-Kota Tinggi Wildlife Reserve. But plantations and other developments had already fragmented the forests and “the area [had] ceased to function as [a wildlife reserve] effectively”.

The report concluded that converting the forest in PTD 216 into plantation is a “non-issue with respect to the status of wildlife reserve.”

In terms of actual species found in PTD 216, the 59 species of mammals reported constitute almost 20% of all mammal species recorded in Peninsular Malaysia. They include the Sunda pangolin and Asian elephant, which are respectively Critically Endangered and Endangered.

These mammals and other animals would be killed or displaced if the forest is cleared.

However, the EIA report argues that “such impacts are buffered by the fact that there is very little wildlife left in the Project Area and that any species which might be affected are neither endemic nor rare and endangered.”

The Wildlife and National Parks Department of Peninsular Malaysia (PERHILITAN) did not respond to questions on the report’s assertions.

Economy

While the development in Jemaluang and Tenggaroh has destroyed ecosystems and habitats, has it delivered the economic benefits touted in the EIA reports?

This is critical in light of the upcoming developments that will destroy yet more ecosystems and biodiversity.

Logs harvested from AA Sawit’s and Nadi Mesra’s plots in Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests respectively have kept local sawmills running. Two sawmill operators in nearby Kota Tinggi told Macaranga that AA Sawit and Nadi Mesra have been the main suppliers of logs in recent years.

When loggers cannot log

Miss Teo is the secretary of Kemajuan Loong Seng Sdn Bhd, a logging and timber trading company in Kota Tinggi. They have been logging forest reserves in the area for about two decades with licenses from the Johor state forestry department.

However, the department has cut back on logging licenses for forest reserves. “Last year we weren’t allowed to log. It wasn’t just because of the pandemic. The government cancelled the licences,” says Teo.

“Even the [logging] quota that had been allotted was retracted. No compensation, just cancelled.”

When Kemajuan Loong Seng’s sister sawmill ran out of logs, “we had no choice but to buy from them [AA Sawit and Nadi Mesra].” And desperate buyers cannot bargain.

“That’s why log prices have been increasing – because supply has reduced.”

Can their business carry on? “Even if we could continue, it would be very hard because we don’t have our own plots to log,” she says. “We could only try to last as long as possible.”

If AA Sawit and Nadi Mesra had not been logging, “we would be badly affected,” says another sawmill operator who requested anonymity.

He concurs that the limited log supply has led to steadily rising prices. “Business is too challenging, and we had to shrink our operations, else we would be like having a large kitchen without rice to cook.” He claims to be running at one-third the capacity he used to two decades ago.

Macaranga reached out to the Johor state forestry department but they did not comment on the effects of logging in Jemaluang and Tenggaroh. They also did not explain why the logging quota in forest reserves was frozen.

However, Sultan Ibrahim had reportedly advised the forestry department in 2014 to freeze logging quotas in forest reserves. He also said he had since that year “surrendered” all his logging quotas in state forest reserves.

However, such state quota control does not restrict logging on private land. And logging on private land has overtaken that in forest reserves in the vicinity of Jemaluang.

So who has benefitted from the development of the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests so far?

Nadi Mesra, who is developing PTD 217, has.

In the 12 months since it started logging that plot, it recorded RM 18.2 million in sales and RM 3.4 million in profit before tax in 2019, according to financial statements available through the Company Commission Malaysia.

It had been running losses the two years prior. A staff confirmed that the company has operations only in Jemaluang-Tenggaroh.

AA Sawit’s financial statements are not available through the Companies Commission of Malaysia.

The Community

He knew the elephants were about, but they had not caused trouble for a long while, so Su Chun Fa (transliteration) did not bother to install electric fences. “I was careless,” says the Jemaluang resident who has lived there for most of his 75 years.

Then, in 2016 or 2017 – “I don’t remember when. I was moody” – the elephants showed up and ate all the young oil palms in his estate.

Su abandoned his plot. “I am old, so I gave up … I’m just waiting to sell the land,” he says.

He recalls that two decades ago, the elephants “were not so fierce, but now they come in herds.” They eat oil palm, trample vegetable beds, and damage property.

Elephants have long been a part of the area’s history and landscape. But they “are our main issue now,” says Su.

Human-elephant conflicts are linked with the loss of the animal’s forest habitats, and the troubles in Jemaluang have coincided with the clearing of the Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests.

The hotspot of human-elephant conflict is along the main road running through Jemaluang town and alongside the forests.

The two forests harboured 20–30 elephants in 2018, according to PERHILITAN statistics cited by EIA reports. Elephants travel far in search of food, and in that landscape of plantations, farms, and villages interspersed between forests, they cannot avoid humans.

Encounters can be unpleasant, even fatal, for both elephants and humans. Elephants have been killed on the road or poisoned.

Managing the crisis in Peninsular Malaysia has cost the authorities more than RM 22 million in the last decade. This sum paid for electrical fences to stop elephant intrusion into agricultural land; to capture and translocate elephants; and outreach programmes.

The interventions worked to a certain degree. Yearly elephant-related complaints in Johor dropped from over 400 to 70.

But human-elephant conflict persists. And in the Jemaluang-Tenggaroh area, already a hotspot for such troubles, future conversion of forests into plantations will force humans and elephants into ever closer contact.

Serene and clean Jemaluang

Despite the elephant concerns, Jemaluang residents seem to enjoy life in town. Most of the residents are above 50 years old, and they have seen their town change.

A good number can recall a Jemaluang bustling with loggers and tin miners in the 1960s and 1970s. The place is now a backwater, which seems to suit the seniors there.

“This is a great place to retire. The air is good,” says Su, the 75-year old who lost his oil palm to elephants. Like many others in the community to whom Macaranga spoke, his main frustration is with the elephants.

Government officers “would come and check if we report [elephant disturbance], but nothing comes out of it. There’s no compensation, nothing. Nobody’s responsible,” he claims.

Is he upset with the forest loss around town? “We don’t care much because we are already old … we just live out our twilight years here.” He also believes that the projects are run by the state government and non-negotiable.

State of private projects?

Most of the residents apparently share the sentiment that little can be done to save the forests. A survey of 183 Jemaluang residents in 2020 by the EIA consultant for the PTD 216 plantation showed that almost all expected logging and oil palm plantations to damage the environment and aggravate wildlife conflict.

Yet only 19% disagreed with that development. About 63% of respondents sat on the fence, mainly because they thought it was a state government project.

In actual fact, all the current and future projects – logging, oil palm, gold mining in the excised Jemaluang and Tenggaroh forests are private projects on private land.

With more projects in the pipeline, Jemaluang residents can expect to answer more surveys. With every survey, they can also expect more changes to their environments and their businesses.

It remains to be seen, in a decade’s time, if Su’s children would like to retire in Jemaluang too.