WASHINGTON — A federal appeals court panel has ruled for the first time that prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, are not entitled to due process, adopting a George W. Bush-era view of detainee rights that could affect the eventual trial of the men charged in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

The 3-to-0 decision issued on Friday by Judge Neomi Rao at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the indefinite detention of Abdulsalam Al Hela, 52, who argued for release by saying that the evidence against him relied on anonymous hearsay and that he never joined or supported Al Qaeda or any other terrorist group.

A U.S. District Court earlier found that Mr. Al Hela, a Yemeni who fought in the U.S.-backed jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, became "a trusted member of the international jihadi community for decades" by helping would-be terrorists with travel and false identities.

But the appeals court judges were split on how and whether to address the broader question of whether Mr. Al Hela was entitled to the same due process protections as a U.S. citizen.

"The Due Process Clause may not be invoked by alien without property or presence in the sovereign territory of the United States," Judge Rao wrote, a position also taken by Judge A. Raymond Randolph.

Judge Thomas Griffith wrote that the court did not need to decide the overarching due process question and could have more narrowly upheld the Yemeni prisoner's detention.

In 2008, the Supreme Court decided in Boumediene v. Bush that Guantánamo detainees can challenge the lawfulness of their detention in federal court by filing writs of habeas corpus. The Supreme Court has not taken a Guantánamo case since, and in the intervening years the lower courts have evaluated the detention of detainees individually.

But the decision by the appeals court to weigh in on the due process question may have implications for the Sept. 11, 2001, trial at Guantánamo. Defense lawyers in the case are trying to exclude the 2007 F.B.I. interrogations of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and four other men accused of plotting the attacks, arguing they are tainted by the detainees' torture in the C.I.A. prisons between 2002 and 2006.

Prosecutors in the death-penalty case have consistently argued that the only constitutional protection Guantánamo prisoners get is the right to challenge their detention through habeas corpus, a civil action. The Al Hela decision, if it stands after any appeal, could bolster their position.

"Boumediene did not create a new framework for lower courts to incorporate constitutional rights beyond our nation's borders," Judge Rao wrote.

Congress built in some statutory protections for the prisoners when it created the war court in response to the Sept. 11 attacks. For example, it forbids the use of self-incriminating confessions gained through cruel and inhuman punishment, such as torture.

But it does permit prosecutors to use what another prisoner said against a defendant gained through coercion — an exception defense lawyers have challenged as violating the constitutional right to due process. Defense lawyers have argued for years that the military judges should also apply other constitutional protections, such as Miranda rights and access to lawyers before the prisoners were charged.

The appeals court decision means the Guantánamo judges may not see themselves as obliged to consider those rights through a constitutional lens.

"No court ever expressly held that the due process actually applies," said Brenner M. Fissell, a law professor at the Hofstra law school who has worked on Guantánamo's detainee appeals at the war court. "Now we have literal language at the court that is reviewing the criminal cases that no one who has person or property and is not a citizen can invoke the due process clause."

Mr. Fissell said the decision harks back to the era before habeas corpus when the Bush administration sought to "carve out this weird island, their weird zone as a legal terra incognita," essentially a constitutional no-go zone.

Mr. Al Hela's lawyers describe him as a lifelong Yemeni resident who was seized while in Cairo on a business meeting in September 2002, was tortured in secret prisons and was delivered to Guantánamo two years later. The 500-page summary of a sweeping Senate study of the C.I.A. overseas prison network, which spells his name as Abdul al Salam al Hilal, lists him as having spent more than 590 days in CI.A. custody.

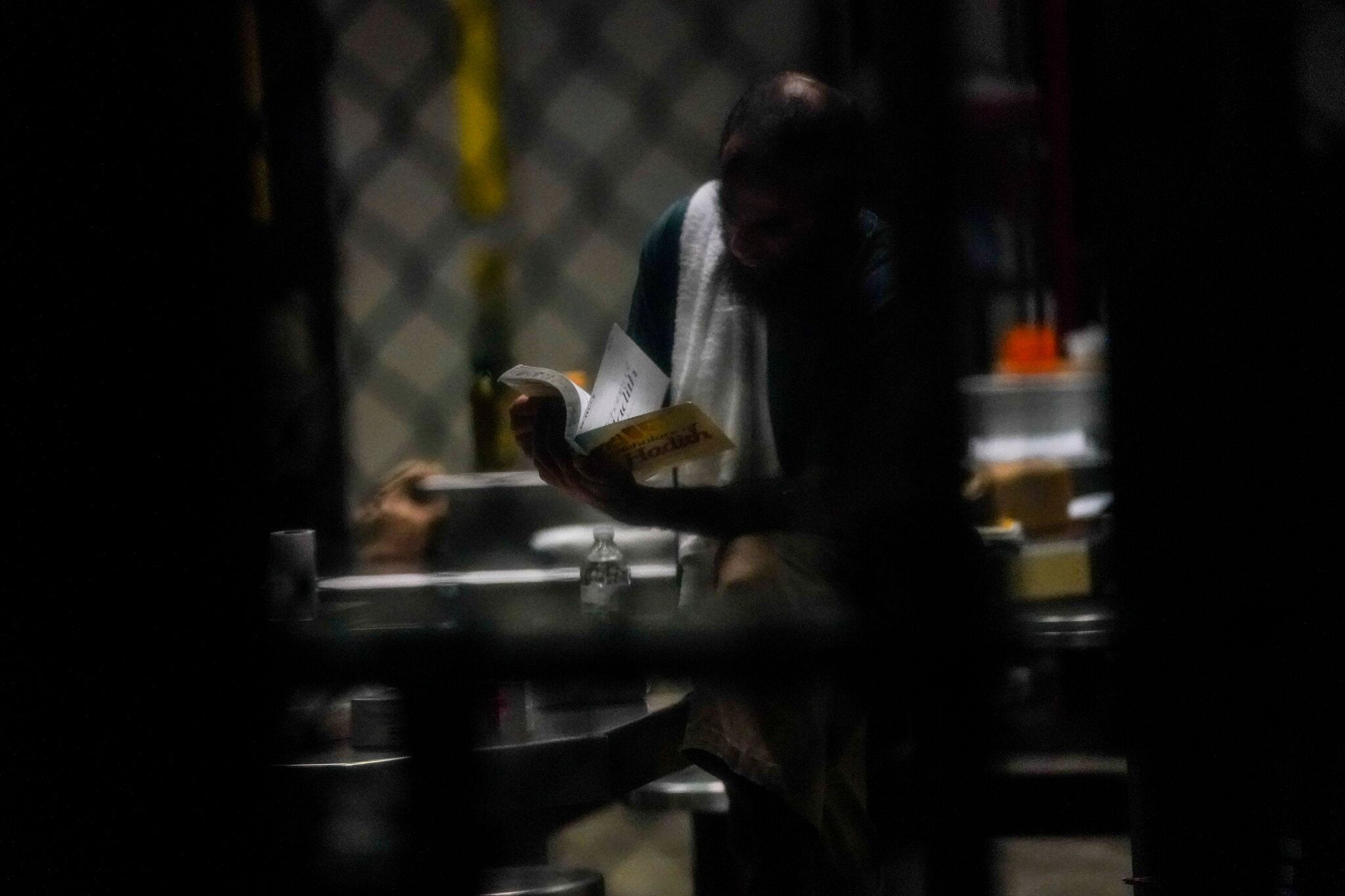

His status at Guantánamo is as a Law of War prisoner. He is among 26 of the 40 detainees there who are in that category — considered too dangerous to release but facing no criminal charges, commonly known as an indefinite detainee or forever prisoner.

Mr. Al Hela's long-serving pro bono lawyer, David H. Remes, said on Tuesday that his legal team was arranging a telephone call with the prisoner at Guantánamo to discuss whether to appeal the decision to the full appeals court.

Judge Rao, who previously worked for the Trump administration, is among the more conservative judges at the appeals court. The full court this week reversed a 2-to-1 decision she wrote in July that ordered a lower court to drop a case against Michael T. Flynn, President Trump's former national security adviser.