View the full interactive experience on The Baltimore Sun website

The car came screaming through the rain-slicked intersection in downtown Baltimore that August night, slamming into Serigne Gueye’s Hyundai Sonata and spinning it nearly 360 degrees.

Gueye, an immigrant from Senegal with a pregnant wife at home, sat battered and stunned. His car was totaled.

“The shock was very, very terrible,” he would say later.

A couple of blocks away, Sgt. Wayne Jenkins’ squad of corrupt plainclothes police officers lingered, debating whether to help clean up their latest mess or slip away without anyone ever knowing they were there.

They had been chasing the first car just prior to the crash — planning to stop it on a pretext, hoping they might find a gun or drugs when they did. The fleeing driver had blown through a red light, struck Gueye’s vehicle and hit a building near the University of Maryland Shock Trauma center.

Surveillance video footage shows bystanders trying to help, followed by arriving patrol officers.

“That’s the thing with Wayne. He’s a little too much with this s---,” Detective Daniel Hersl observed as the officers watched from afar, his comments captured on a secret microphone placed in the car by federal agents. “These car chases — this is what happens.”

The officers wondered if they’d already been implicated by surveillance cameras. Maybe they could change their time cards, one suggested, so no one would know they’d been on duty.

Another said not to worry; he thought the people in the accident were unconscious anyway. Then, over the police radio, the word came down from their leader:

“Go back to headquarters,” Jenkins said.

So they did. Someone else could tend to the people in the smashed-up cars, two of whom were taken to a hospital for treatment. No one needed to know that speeding plainclothes cops in unmarked vehicles had caused the wreck.

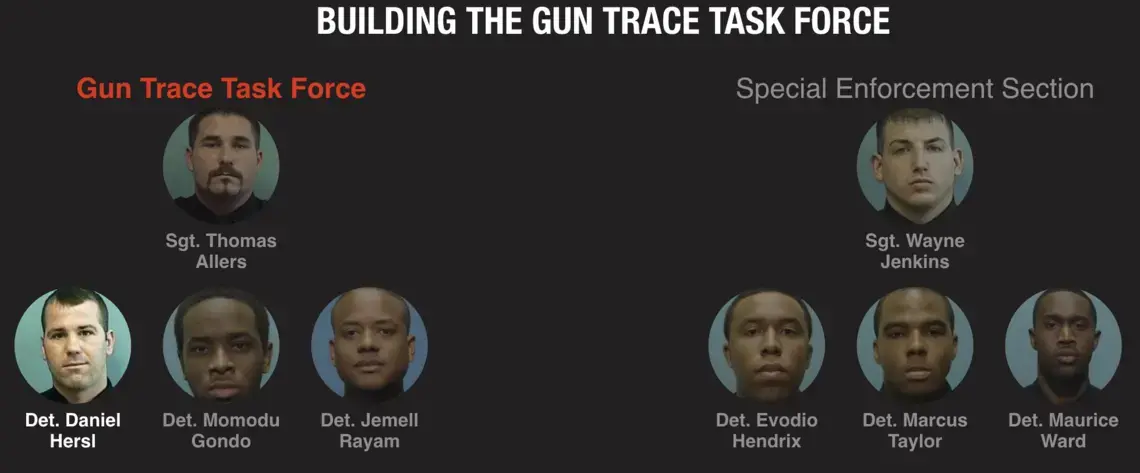

At the time of the crash in the summer of 2016, Jenkins, then 36, had dodged repeated accusations of wrongdoing and been put at the helm of the Baltimore Police Department’s reconstituted Gun Trace Task Force — the latest in a series of variously named elite squads charged with making a dent in Charm City’s pernicious crime rate.

Jenkins was a chronically crooked cop who for at least several years had been stealing drugs and money seized from city residents under the guise of collecting police evidence. Sometimes he arrested the suspects, sometimes not.

The acclaimed sergeant brought to the squad three men who’d worked under him in the past — and who had shared in some of the illegal bounty.

They were joining a team, it turned out, already staffed with some like-minded officers who had engaged in similar activity.

But to keep operating in the plainclothes unit — and enjoy the lack of supervision that came with the assignment — they had to get the job done.

The job of the Gun Trace Task Force was to get guns off the streets of Baltimore. That endeavor might have involved methodical investigations in which officers painstakingly assembled and documented evidence needed for search warrants that could lead to the collection of illegal firearms.

But often, Sergeant Jenkins’ team preferred to just “go hunting,” as Hersl once described it to a jury.

That is, prowl high-crime neighborhoods of the city, using questionable and often illegal tactics to look for guns, drugs and cash. A favorite method was to swoop in on people not actually suspected of a crime, get into their cars and search. It was the quickest way to get results.

The Baltimore Sun spent a year delving into the operations of the now notorious unit and its leader Jenkins, who was sentenced last June to 25 years in prison for federal racketeering crimes including robbery, extortion and overtime fraud. Six of his officers also are serving time.

In the first part of this series, The Sun described Jenkins’ rise to prominence in the Baltimore Police Department as an officer known for getting things done. Even as he was hailed as effective, there were red flags that he was planting evidence and fabricating facts to justify arrests.

Jenkins was sued at least four times early in his career, with settlements reached or juries finding fault in three of those cases.

A special unit of the Baltimore state’s attorney’s office began investigating his lies and even presented evidence to a grand jury but prosecutors concluded they didn’t have enough to charge him.

Being promoted to sergeant — and taking on responsibility for leading other officers — didn’t diminish his penchant for ignoring rules.

Looking for excuses to stop and search suspects, Jenkins and his squad were frequently involved in high-speed chases and crashes like the one involving Gueye.

Police department records show that Jenkins got into 12 reported accidents involving department vehicles, but he sparked countless more. The number is hard to quantify in part because Jenkins sometimes paid out of pocket to fix the cars. He had a crash bar installed on one of them — using money from one of their robberies, one of his officers said.

Even the less dramatic methods employed by Jenkins and his men involved questionable or improper conduct. Courts have given police great latitude to stop a vehicle for minor infractions, but videos of stops captured by the officers’ body cameras show they often resulted in searches that likely wouldn’t pass legal muster.

Not surprisingly, Jenkins’ arrests often didn’t hold up. A Baltimore Sun analysis of Jenkins’ cases from 2012-2016 found that 40 percent were dropped by prosecutors. In contrast, department-wide about a quarter of gun cases were dropped in 2016, The Sun’s analysis found.

Even while the officers’ cases were being thrown out, judges sought to reassure them that they were doing a good job. “They are in a high-crime area, they’re checking things out and they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing,” Baltimore Circuit Judge Pamela White said, while explaining that Jenkins and his unit had nevertheless violated the Constitution.

“Convey my appreciation to the officers for doing their job, notwithstanding my decision,” she said.

Beyond violating civil rights, Jenkins and his men were routinely stealing from people they encountered in their work, usually suspected drug dealers. The criminal behavior continued even when the U.S. Department of Justice sent investigators to the city for months to examine the conduct of the Baltimore police force.

Jenkins had been with the department for almost 13 years, four of them as sergeant, when he assumed command of the gun task force in June 2016.

Use this link to view The Baltimore Sun's interactive webpage.

As in earlier years, he and his men sometimes left signs of their misconduct. Their supervisors either didn’t see them or chose not to.

Sometimes people in the path of the squad’s behavior knew they were the victims of rogue cops. But not always.

Gueye didn’t know plainclothes officers had anything to do with his accident until told by The Sun. A reporter pieced together information from police reports, dispatch records and court documents to determine that Gueye was the victim of the crash, then located him.

His troubles hadn’t ended that night. The man who crashed into Gueye’s car had sued the West African, claiming reckless driving by Gueye had caused the accident.

Surveillance footage obtained by The Sun through a public records request shows that is not what happened. Made aware of that evidence, Gueye and his lawyer got the lawsuit dropped.

Jenkins and his men had failed to step in to help the injured man after the crash, then failed to point out that they had caused it. He was far from the only victim of their misconduct.

‘ARE YOU NERVOUS, SIR?’

On Aug. 10, 2016, the Justice Department issued a scathing report describing what it learned about the behavior of Baltimore cops during a 15-month investigation. It found, in part, that officers routinely stopped, searched and arrested city residents — especially black men — without reasonable suspicion or probable cause. A panoply of government officials gathered at City Hall to release the findings and pledged a sustained program of reform.

Within hours, Wayne Jenkins and his officers on the Gun Trace Task Force went hunting anyway.

Trolling that evening on downtown’s west side, the team made what was for them a routine traffic stop. About 7 p.m. they spotted two black men in a dark blue, recent model Chevy Impala on Saratoga Street.

Jenkins, always the wheelman, maneuvered into position to cross the center line and drive head-on at the Impala — forcing its startled driver to stop. The encounter was documented on another officer’s recently issued body camera.

Kneeling by the car window, in wrinkled khaki pants and bullet-proof vest stamped “Baltimore Police,” Jenkins announced himself. “I’m Sergeant Wayne Jenkins with the Gun Trace Task Force. The reason you gentlemen are being stopped today is because you don’t have a seat belt on.”

The Impala belonged to the passenger, D’Andre Adams, who was teaching a relative to drive. The officers told Adams to step out of the car, walk toward the rear and face away from the vehicle as they searched the inside.

“You have to wear a seat belt,” Detective Hersl told him.

“That’s cool, but why you searching my car though?” said Adams. “I didn’t authorize nobody to search my s---.”

The approach was standard operating procedure for Jenkins and his unit. In a video from a stop on Liberty Heights Avenue, a driver who just bought gas hadn’t even pulled away from the pump when he and his passengers, all young black men, were approached by the officers. They, too, were told there was a problem because they weren’t wearing seat belts.

Hersl asked them to get out of the car, saying he noticed there was a bag on the floor. He claimed the officers had recovered a gun an hour earlier from a bag in somebody else’s car — as though that were legal justification to search everyone in Northwest Baltimore on a Wednesday evening with a bag in their vehicle.

“Are you nervous, sir?” Jenkins said to one of the men. “You’re shaking really bad, man,” he continued — though the video shows otherwise.

After searching the car, the officers sent them on their way.

In footage from another stop one afternoon, a man eating lunch in his car was asked to get out because he had parked too far from the curb.

“Look at all this space!” Hersl says to him, though body camera video of the stop shows that the distance wasn’t especially great.

The officers asked why he was “acting nervous,” and said his car “reeks of weed.”

Saying someone appears nervous and that officers smell marijuana are key phrases that, if a stop were to be challenged, could provide justification for the search — except the man seemed calm, and correctly insisted they would find no marijuana in his car.

After picking through the vehicle, Jenkins told the man to have a nice day.

“We don’t mess with working-class people,” Jenkins said.

Detectives who worked with Jenkins testified that at his direction, they often profiled men driving certain types of vehicles, which they called “dope boy cars.” They also said they would drive at groups of men standing around in poor black neighborhoods, then slam on the brakes, hoping to provoke people into running so the officers could give chase.

"Everything you learn in the academy is thrown out once you graduate"

“Everything you learn in the academy is thrown out once you graduate,” gun task force member Maurice Ward said in an interview from prison.

Traffic stops are a hallmark of policing in downtrodden neighborhoods. Officers are encouraged to look for the smallest violation to stop a vehicle — a broken tail light, following too closely, a passenger without a seat belt — then engage the occupants and look for cues that can ratchet up the stop into a search.

Because those signs are often subjective — or impossible to prove, such as the smell of marijuana — they are ripe for abuse.

“In fact, they are trained to use these type of techniques,” said David Jaros, a law professor at the University of Baltimore. “The Supreme Court openly says, ‘We have no problem with what is referred to as ‘pretextual stops,’ even if the officer’s subjective goal is something entirely different.”

Such stops are harmful, Jaros said, even beyond the damage to civil rights. They destroy trust between police and the communities they are charged with protecting.

He said people often hear about the stops when they are successful.

“What we don’t see is all those cases where the subsequent stop does not lead to evidence of a crime — and all of the ways that kind of activity undermines the people being policed, and the police in their community.

“A lot of the costs of those activities are hidden,” Jaros said.

During the traffic stop on Saratoga Street Aug. 10, Adams was growing impatient, the video shows. His young daughter was in the back seat of the car, and he was worried about her. Ordered to stand outside and look away, he told officers he wanted to turn around and see what was happening. Adams offered to be placed in handcuffs as long as he could face the car.

“It’s an illegal search,” Adams asserted.

The officers found nothing in the car.

Reached by The Sun, Adams said he is a licensed private detective and security officer. He noted that he was in a dark-colored car with tinted windows — which police seem to consider a “drug dealer car,” he said.

As a black man in Baltimore, Adams said, “you get profiled all the time.”

Former Detective Marcus Taylor took part in many stops like that. In an interview from prison, the convicted Gun Trace Task Force member said they were a necessary part of good policing and did not represent racial profiling.

“Look at the areas where the violence occurs and criminal activity is done in the community — it’s in minority neighborhoods for the most part,” Taylor, who is black, said in a written exchange with a reporter.

“Once you put the vehicle in motion and you don’t have a seat belt on, then I can stop you, look for numerous things. I don’t care what ethnicity, religion, etc. I do not discriminate. I did my job and I was pretty good at it.”

A jury found Taylor guilty of racketeering for his role in the gun squad’s robberies and overtime abuse, and a judge sentenced him to 18 years. He maintains his innocence.

‘I SEEN A CAR FLYING’

Sometimes routine car stops led to explosive results.

Officers have described Jenkins as an adrenaline junkie who relished high-speed chases. A police department tally shows he got into a dozen documented car crashes. Reviewing other records about Jenkins’ cases, The Sun found several more.

To avoid scrutiny from supervisors, Jenkins personally paid for repairs to the vehicles he used for department work. He had a crash bar installed on one of them to minimize damage, and he once gave an officer a $100 bill to get a tire repaired so they would not have to report the damage.

“We had several high-speed chases every day — sometimes the car [being chased] would crash or Jenkins would ram cars,” Ward said. “When he chased cars he always had tunnel vision, and we would have to physically shake or hit him to make him come out of it.”

One night in February 2016, Jenkins and his men chased a Honda Accord through the streets of East Baltimore until it slammed into the steps of the Church of the New Covenant on North Wolfe Street. The impact was enough to deploy the car’s air bags, and a passenger was knocked unconscious.

After they arrested the driver of the Honda, they used a cell phone to videotape a conversation with him. The man said that when he saw a mysterious vehicle gunning for him, he was terrified — and fled.

“I seen a car flying behind me, with no light. No lights at all! Not no flashing lights, no lights period.” Jenkins asked the man why he didn’t just stop.

“Cuz I thought y’all was gonna try to kill me,” he responded.

Among the problems with such policing is that it isn’t very effective. Though the officers said they found a gun on the floor of the Honda, the charge against the driver later was dropped — as were many other charges brought by Jenkins.

But the Baltimore Police Department was doing very little follow-up, operating in a right-now mindset in which collecting guns was mission accomplished, police and prosecutors say. The court cases, which would take months and months to play out, were of little consequence. In Baltimore’s revolving door of criminal justice, it was expected that few offenders would serve hard time, even if caught red-handed.

But they would at least be jammed up for awhile.

A GUN UNIT EMPOWERED

Jenkins’ squad and its misdeeds bore no resemblance to the unit as created a decade earlier. The Gun Trace Task Force was set up in 2007 when then- Police Commissioner Frederick H. Bealefeld wanted to move the department away from “zero tolerance” policing and focus on violent repeat offenders.

As the name suggests, the task force was designed to trace the origin of guns seized on the street. Officers investigated serial numbers, looking into where firearms had come from. In the early years, Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County and Maryland State Police cooperated in the effort to identify and catch area gun traffickers.

But in 2013, a consultant’s report ordered by new Commissioner Anthony Batts concluded the Gun Trace Task Force was an underutilized asset in the crime fight. Instead of focusing on gun traffickers and straw purchases, the task force would spend more time out on the streets looking for illegal guns.

Then came the death of Freddie Gray and the rioting of April 2015. That summer gun violence soared — and never diminished. By year’s end, shootings in Baltimore were up 60 percent over 2014, and arrests plummeted. The police union said officers were afraid to do their jobs for fear they’d be charged, as the officers were in Gray’s death. Others said it seemed that cops were “taking a knee” en masse to protest the arrest of the officers.

In July, Batts was fired amid the unchecked violence. New Commissioner Kevin Davis called a meeting of plainclothes units in the department’s auditorium.

A deputy commissioner, Dean Palmere, did much of the talking — and issued the charge. To Eric Kowalczyk, a police captain and the department’s chief spokesman at the time, the message was ominous.

“Here was one of the most senior people in the organization telling plainclothes officers to go out and do whatever it took to reduce crime. Whatever it took. That mentality and operating modality were the exact reasons we had just gone through a riot,” Kowalczyk wrote in a recently published book.

“No lessons had been learned.” Kowalczyk decided that day to retire, short of his pension.

Still, by May of 2016, little had changed. That month, 38 people were killed, rivaling the numbers of the summer after Gray’s death. Arrests still lagged, with officers complaining about morale. An oft-cited reason continued to be that police believed prosecutors were over-scrutinizing their work, making officers afraid to do their jobs.

Not Jenkins’ plainclothes team. In 2015, they’d received a certificate of commendation from the No. 2 man in the department, Palmere, for making 103 handgun arrests and seizing 100 guns over the course of the year.

“Sergeant Jenkins’ squad was the only one producing post-Freddie Gray,” Lt. Chris O’Ree would later tell Internal Affairs investigators trying to ascertain the role of supervisors in the corruption scandal.

In June 2016, police department leaders again expanded the mission of the Gun Trace Task Force. It would soon be viewed as a “tier one asset,” O’Ree said.

And to head the unit, Palmere handpicked Jenkins.

'THEY STOLE IT’

Raytawn Benjamin and a couple of friends were standing on a corner in Pigtown when Jenkins and two members of his plainclothes squad pulled up alongside them. The officers would later say Benjamin had “displayed characteristics of an armed individual” and that he tossed a gun into a truck as they chased him.

Benjamin, 18, was taken to jail on a handgun violation and ordered held without bond.

He placed a phone call over the recorded jail system to a female relative, recounted in previously sealed court documents obtained by The Sun.

“They took like 400 from me,” Benjamin said.

“And they didn’t put it in the report, did they?” the woman said.

“Nope.”

“They stole it,” she said.

Benjamin was arrested a few months before Jenkins was promoted. The sergeant was routinely robbing suspects long before he was made head of the Gun Trace Task Force.

And some Gun Trace Task Force members likewise were pocketing cash long before Jenkins became their boss, court records show.

Ward says he was stealing money before winning the coveted assignment to plainclothes work in 2013.

He described the thefts as a casual and uncoordinated activity, with officers quietly skimming money off those they arrested. “It was basically just a bunch of dudes out for [themselves,]” he said.

To a uniformed cop, Ward said, plainclothes units were hard to break into unless you had connections. A way to build connections, he said, was to show you could be trusted — which meant covering for others.

“I can say that I stole money before Jenkins, not because I was poor [or] struggling,” Ward told The Sun.

Rather, it was “just because everybody else was doing it, and I wanted to feel accepted and trusted to get into a specialized unit and out of patrol.”

Once Ward went to work for Jenkins, he was surprised to discover just how much his new sergeant crossed the line. The officers would typically arrive to work late so they could work at night and submit inflated slips for overtime. They’d review department emails to see where the latest shooting had occurred so they could attack that area, looking for excuses to stop as many people as possible.

“We learned very quickly that it was a numbers game — the more people you come in contact with, the greater your chances of getting a gun,” Ward said.

Despite all the corner cutting, Ward said, Jenkins had assured his officers they didn’t have to worry about repercussions.

“Any [Internal Affairs] complaints, he promised we would be taken care of because of his connections,” Ward said.

Jenkins expressed ambivalence about arresting people for drugs, arrests that earlier in his career had helped him build his reputation.

Now, the sergeant would often cut drug suspects a break and let them go without charges, Ward said, collecting the narcotics and telling the officers he’d submit them to evidence control.

Jenkins always transported the drugs himself — something that wouldn’t seem odd to Ward until later.

Baltimore Sun data reporter Christine Zhang contributed to this article.

![Click on each officer to read details about incidents they had while in the Baltimore Police Department [using the link below]. Image courtesy of The Baltimore Sun.](/sites/default/files/styles/1140x695_scale/public/screen_shot_2019-06-13_at_10.25.21_am.png.webp?itok=VWUrmeyW)

![Click on each officer to read details about incidents they had while in the Baltimore Police Department [using the link below]. Image courtesy of The Baltimore Sun.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumb_80x80/public/screen_shot_2019-06-13_at_10.25.21_am.png.webp?itok=-dEi1bgo)