Braving the threat of more terrorist attacks, leaders from 196 countries gather in Paris tomorrow under heavy security for the 21st annual attempt by the United Nations to cope with what virtually every climate scientist believes is a looming, self-induced calamity for humanity.

If you don't think climate change is real or man-made; if you don't believe the last 15 years have been the hottest in recorded history; if you don't agonize over photos of the Arctic melting or recognize that sea-level rise is stealing the Carolina coast, then the U.N. climate summit in Paris means nothing to you.

But I ask you to care. I beg you to listen. And, please, don't just take my word for it.

Pope Francis is perhaps the most popular, trustworthy figure on earth, whether you are Catholic or not. Maybe you see him restoring credibility to a damaged Catholic Church. Maybe you admire his statement, "Who am I to judge?" Maybe you are inspired by his humanity, humility and insistence on eschewing the trappings of papal luxury to live more like the poor whom he champions.

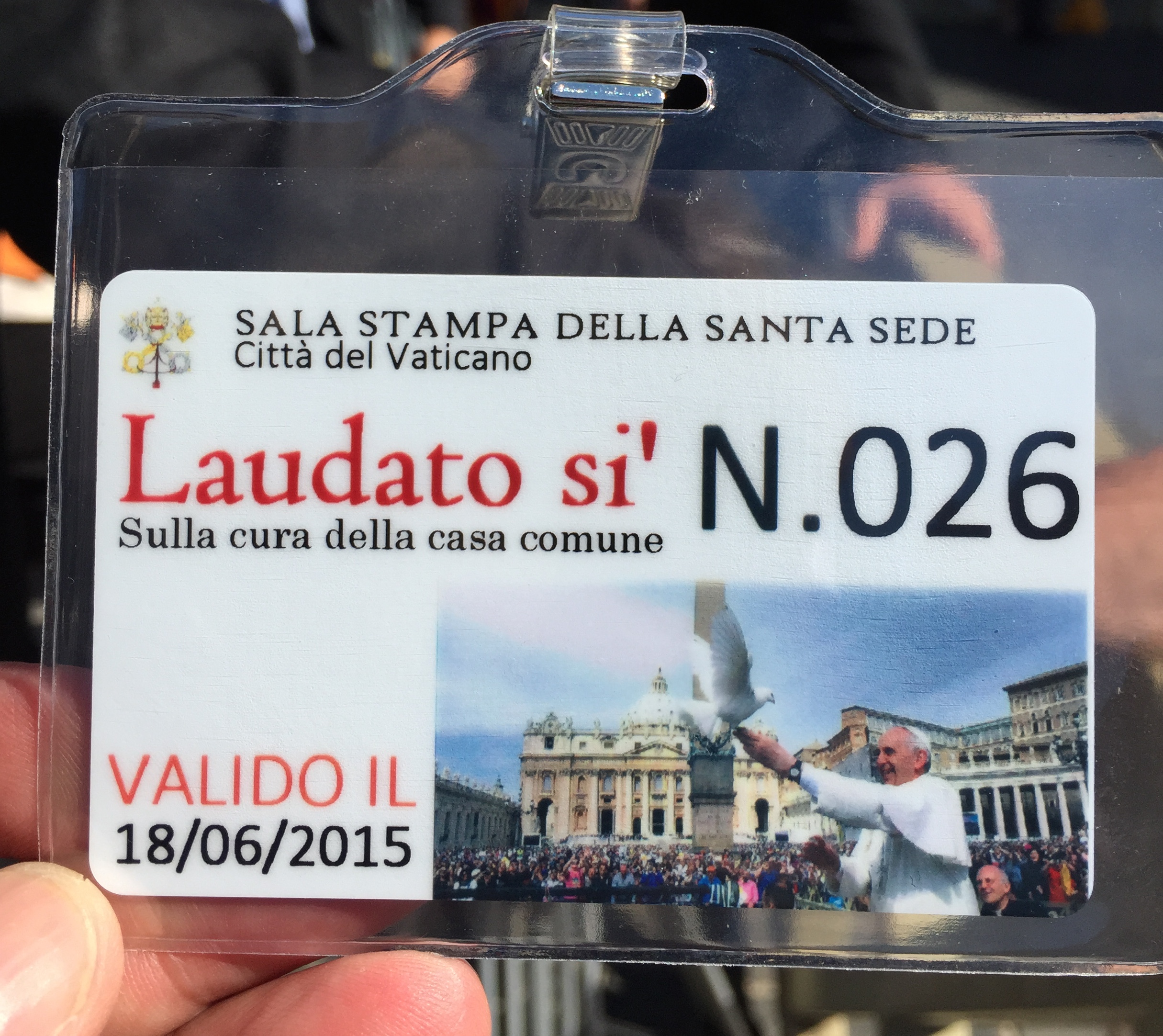

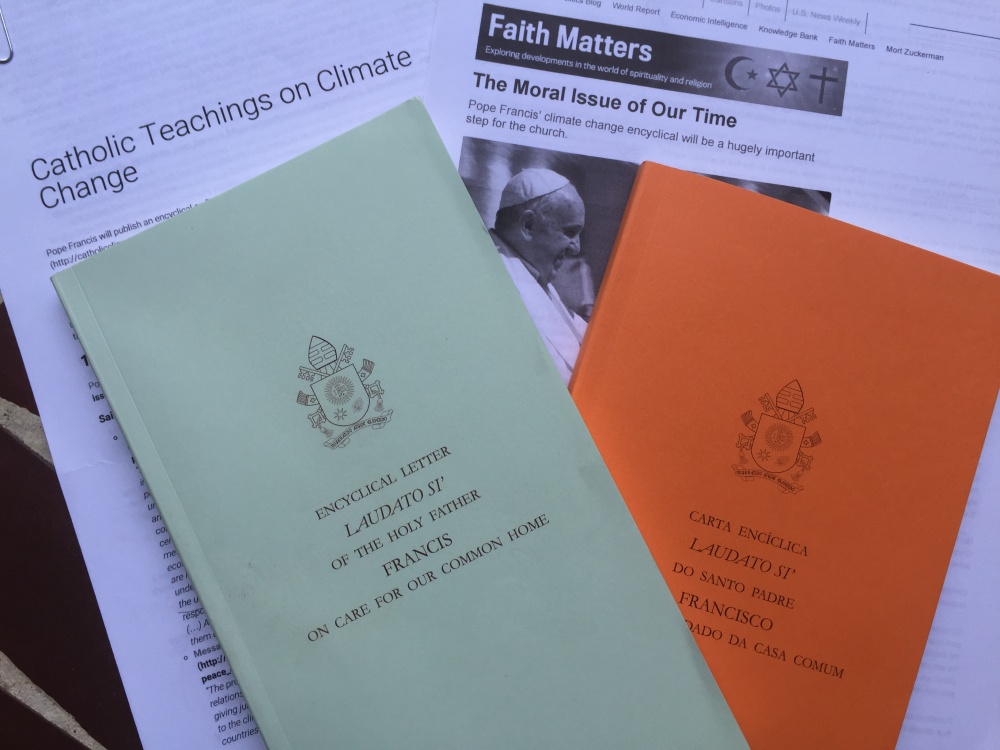

If so, you should know that the world's highest-profile religious leader has boldly stepped into a yawning vacuum of political leadership to shout in a rare papal encyclical, or teaching document, released last June:

"Climate change is a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods," he writes in "Laudato Si, On Care for our Common Home."

"There is an urgent need to develop policies so that, in the next few years, the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases can be drastically reduced."

Here's why Francis says that. Here's why the outcome of the negotiations in Paris is crucial. Here's why you should care.

Some 160 years ago, before the dawn of the industrial age, the amount of carbon in the atmosphere was around 240 parts per million. That natural carbon shield provided an ideal greenhouse effect, a protective blanket in the sky. It allowed in plenty of the sun's heat, but when the sun reflected back from the earth's surface, it let the right amount of heat escape into outer space. The greenhouse effect enables life on earth.

Today, largely because of burning of oil, coal and natural gas for energy production, atmospheric carbon is now 400 ppm. The earth's blanket is thicker; less of the sun's reflected heat escapes. And we have been warming steadily — nearly 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit since 1900.

The results of this warming are neither hypothetical nor far in the future. They are with us now and getting worse. Prolonged drought in California. Island nations sinking in the South Pacific. Typhoons of incomparable ferocity in the Philippines.

If we continue burning fossil fuels at our current rate, global temperatures are projected to rise another 6 degrees to 9 degrees before the end of the century (along with sea-level rise topping 20 feet).

Look at it this way. Normal body temperature is 98.6 degrees. If your fever spikes to 107, how do you feel? Dead. It's a telling analogy. Many scientists believe we are on that path, and that life on earth, which is already more difficult in poor, overheated tropical countries, could become unsustainable.

Hope and a gap

The task in Paris is both simple and complex. Since the last U.N. summit in Lima, Peru, last December, which I covered, more than 150 nations have voluntarily pledged to reduce their burning of fossil fuels. The United States, for example, by 2025; China by 2030. Those pledges, and many other issues, will be written into a global accord.

Let's be clear. Just 10 industrialized nations (if you count the European Union as one) account for 75 percent of all emissions; if only those 10 agree to act aggressively, there's hope. John Knox, a Wake Forest University law professor and special representative to the U.N. for climate change and human rights, says is he optimistic.

"Paris will be different for two reasons," Knox says. "For the first time ever, the three biggest carbon emitters — China, the U.S. and the EU — are on board. Also, the U.N. is taking a bottom-up approach, with countries offering to do what they can, rather than the top-down, do-what-we-tell-you approach that failed for two decades."

The goal of any agreement signed in Paris is to keep the earth from heating up by more than another 1.8 degrees in the next 75 years by burning far less oil, coal and gas, and instead shifting to renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydroelectric and nuclear. Life on earth will become more difficult still by adding another 1.8 degrees, but for most of us, it would be manageable.

Yet Knox has done the math. When the voluntary emission pledges are totaled, they account for only half the reductions required to stay under the 1.8 degree target. Half. But keep in mind, he adds: Paris is not an end point, it's a pivot point. More aggressive action post-Paris is expected, he says.

Papal influence?

But politicians, particularly conservatives in the U.S. and Australia, oppose anything that threatens oil, gas and coal industries. China, though determined to clear its smog-choked skies, is still burning coal like crazy to power its growing cities and factories. So is India, which is desperate to lift its people out of poverty.

So what can a pope do?

Well, Pope John Paul II is often credited with helping bring down communism. Can Pope Francis save the earth?

I spent three weeks reporting in Peru last summer, a Catholic country where the first Latin American pope enjoys 82 percent approval ratings. I spoke with government and business leaders, clergy and economists. I spoke with jobless workers in a town 14,000 feet high in the Andes. Every resident has been poisoned by a noxious, 77-year-old copper smelting plant that shut down when pollution regulations tightened. Some 1,600 workers in the town of 33,000 are now jobless.

Emel Salazar Yuriuilca, who represents the unemployed in her town of La Oroya, professes a deep pride in and love for Pope Francis. But she told me the plant must reopen: "The life of that (smelting) plant is more important than anything the pope says. Yes, we are poor. But that's because the plant closed."

Even among the poor he strives to defend, the pope's moral authority on an issue as fraught and complex as climate change appears limited.

But Robert Mickens, a journalist in Rome who has covered the Vatican for 25 years, cautions not to underestimate the influence of Pope Francis on climate change policy.

"No other world leader, religious or otherwise, has made this such a high priority," Mickens says. "And because it has become such an urgent issue, Francis sees it as something that can galvanize the human family, despite our differences of creed, ideology, color or nationality. There is only one sandbox. And we're all in it together."

Elizabeth Gandolfo, a professor in Wake Forest's divinity school, adds, "There are people of many faiths who have been calling for ecological responsibility for decades. Now Francis and other religious leaders at global grassroots levels are showing us that our deepest moral values are calling us to care for our common home."

Listen closely to what Mickens and Gandolfo are saying. Politicians are likely to keep failing us. But in churches and synagogues, neighborhoods and cities, we should not fail ourselves. It's our sandbox, too.

And this pope, at this time, appears ready to set a global example. His presence in Paris could be galvanizing all by itself.

"Will the pope's leadership continue to be more than just pastoral engagement?" asks Evan Berry, an associate professor of philosophy and religion at American University. "Will he show up to put direct pressure on the heads of state whose nations are lagging? I hope so."

It's a lot to expect of one man, even a popular pope. But Francis has made his intentions clear in "Laudato Si": "Humanity is called to recognize the need for changes of lifestyle, production and consumption in order to combat this warming." Perhaps he will shout just that in Paris.