Late in the evening, grainy footage flashed across Mimi Mefo Takambou’s screen of the Mamfe District Hospital in Cameroon burning to the ground. 3,500 miles away in the United Kingdom, the reputed Cameroonian journalist began calling trusted sources and scrounging the evidence as it poured in online. Early the next day, June 9, 2022, her highly-trafficked pages announced: “Suspected separatists have set the Mamfe district hospital on fire.”

Suspected separatists have set the Mamfe district hospital on fire. Last night's incident which has left the entire structure in ruins followed an intense exchange of gunshots. The exact number of casualties is not known.

-------------

Contact Us On WhatsApp: +237679135573 pic.twitter.com/mrDXSfps8x— Mimi Mefo Info (@MimiMefoInfo) June 9, 2022

In the comments section below, Takambou’s headline sparked almost as much controversy as the arson itself. “Separatist fighters […] attacked me online, did everything for the Mimi Mefo Info platform to come and say that they were not responsible,” she said in an interview. Other accounts seemed to support her claim, and a war of words ensued online.

In Cameroon’s ongoing civil war, even those who survive the crossfire outside their doors cannot escape it on their smartphones. Orchestrated chaos on social media is depriving Anglophones of the clarity they need to make safe decisions, hold offenders accountable, and mourn their losses.

Constant clashes online mirror a real war—the one that brought most of the Mamfe District hospital to the ground. Since 2017, colonial-era cultural and political tensions have fueled violent conflict in Cameroon between the state military, controlled by an entrenched Francophone administration, and Anglophone separatist fighters, vying to create an independent state called Ambazonia. The conflict is known as the Anglophone crisis.

Since the first firefights in September 2017, government and separatist supporters have traded accusations on social media whenever wartime atrocities came to light. In the northwest and southwest regions of Cameroon, schools and homes have burned, and civilians have lost their lives, without any claims of responsibility.

On social media, “if you see someone who is confused, they have got an agenda,” said Takambou. With her mixed heritage as a daughter of a Francophone and an Anglophone, and her record of reporting atrocities on each side of the conflict, Takambou is in many ways caught in the middle.

It’s a unique and perilous position for a journalist. “The government would say that I work for the separatists, and the separatists will say I work for the government,” she said.

Neither accusation comes lightly. Takambou was imprisoned in 2018 for tweeting about war crimes committed by the Cameroonian military. Unlike many of her colleagues, who have been jailed, tortured, and killed for reporting on the Anglophone crisis, she was released after four days, as an online movement (#FreeMimiMefo) quickly mobilized in her defense.

The incident showed Takambou how dangerous her job as a journalist was—and how social media could help her keep it.

Takambou is now based in Germany and the United Kingdom, from where she runs a team of about 20 reporters in Cameroon who write news for her site. She is prolific on social media, reaching almost half a million followers on her Facebook page alone. Takambou’s site has become a central cog in a new media machine, one that is steering traditional news media—and Cameroonian society—into an uncertain future.

Cameroon boasts over 500 newspapers, 150 radio stations, and dozens of television news channels to date. Takambou first found success as a broadcast journalist and editor-in-chief of English services at Equinox TV, Cameroon’s largest private news channel. Nonetheless, journalism—especially about the Anglophone crisis—is moving en masse to social media.

The digital revolution is old news in wealthier parts of the world, though its rise to prominence in Cameroon was relatively recent and dramatic. According to the World Bank, 10 times as many Cameroonians are connected now as in 2010. Today, colorful phone service kiosks and ads populate the streets of major cities.

Amid the Anglophone crisis, the online exodus of news has delivered mixed results.

“[We’ve seen] so many atrocities exposed on the social media,” Takambou said. Online platforms level age-old barriers to gathering and distributing information, offering reporters, witnesses, and whistleblowers a digital buffer from those determined to keep them quiet.

"So that is the good side of the internet, but the bad side is that it's also a tool for propaganda."

Mimi Mefo Takambou

The same anonymity and influence enjoyed by war reporters also empowers warriors—and makes it much harder for audiences to tell who is who.

Christian Tatchou Nounkeu, an Anglophone Cameroonian pursuing his doctorate in Sweden, has studied how online ambiguity helps fuel the Anglophone crisis.

“You present yourself as an activist, and at the same time as a citizen journalist who will be providing the public with information,” Nounkeu said in an interview. “It drives people in being for or being against a cause […] without providing them with the right information.”

Disinformation comes from every side of the conflict.

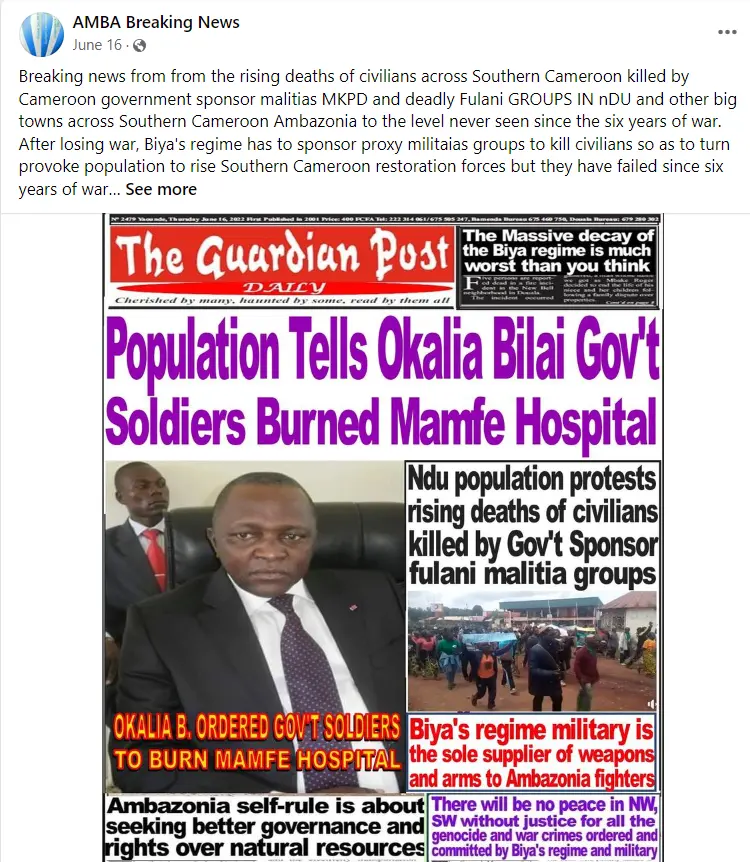

Reflecting an awkward transition from print to online news, separatist activists sometimes publish altered screenshots of the daily front pages, misleading online audiences to believe established sources support a given narrative.

Similarly, separatists spread false—and sometimes outlandish—claims to recruit new members.

“They told them that a bullet literally cannot penetrate an Amba boy [a nickname for separatist fighters],” said MB, a pro-government activist (who asked not to be named) during an in-person interview. Theatrical demonstrations on Facebook show Amba boys being “shot”—presumably using blank cartridges—and surviving unscathed thanks to “black magic.”

MB knows how pro-separatist accounts work on social media because he runs some of them.

His goal is to turn the separatists’ tactics around on them, using disinformation and blackmail to neutralize rebel fighters and their dreams of Ambazonia. Impersonating separatist coordinators or citizen journalists online, the activist runs non-state armed groups into traps, publishes disparaging reports, and helps spark infighting between separatist factions.

“If I know that it will […] cause a rift between them to kill themselves,” MB explained coolly, he will spread lethal lies online "without blinking."

As separatist factions splinter and major outlets shy away from reporting, discerning useful facts from lethal fiction has never been more difficult—or more important.

“Now that the situation is worsening, we have fewer people reporting on the conflict,” Takambou said. “Why is the Anglophone crisis so under-reported?” she asked, years' worth of frustration tinting her voice. “It’s like a people have just been abandoned.” Cameroon does have some fact-checking sites, though researchers broadly lack the resources and security they need to report on the ground.

“At the start of the crisis […] people were willing to share their experiences,” said Mbuh Stella, a professional fact-checker and journalist from the southwest region. But by 2018, her sources dried up. “People were scared, either by being attacked by the government […] [or] of being attacked by a separatist.”

Journalists, like their sources, have every reason not to speak up. “When [separatists] start pointing at you and calling you an enabler or a traitor,” Stella said, “your head will be displayed on the nearest road junction.”

“We cannot continue to work like this forever,” Takambou said. She dreams of establishing her own media house back in Cameroon, when journalists are able to “work freely, write reports, [and] byline them with our names without being scared.”

“That's what I'm looking forward to,” she added. “I cannot wait.”

Building freer and safer information channels will be hard, Takambou admitted. Nankou would like to see tech giants take more responsibility for the disinformation spread on their platforms, though he also advocates for more media literacy education in Cameroon. Stella urged politicians to focus on curbing disinformation and hate speech, rather than using cyber-terrorism laws to persecute journalists and political opponents.

"We just need change in Cameroon," Takambou concluded, alluding to the decades-long rule of the current administration. “If [President Paul Biya] didn't do anything 40 years ago, he is not going to do anything now.”

In the meantime, social media can play a powerful, though risk-prone, role in crowdsourcing information; it also gives many Cameroonians in the diaspora their only connection to loved ones in war-struck Anglophone regions. Most promising, social media can help bring attention to wartime injustices that would otherwise fly under the international radar—as in 2018 when an online movement "hashtagged" Takambou out of her prison cell.

In the eyes of Eugene Ndi, Yaoundé chapter President of the Cameroon Association of English-speaking Journalists, an internet connection can be a life-saver when handled with caution.

Cameroonians—especially those living in warzones—"must not abandon the social media,” Ndi advised. “But they should be careful,” he warned. “Before they take any decision based on what they have read on Facebook, they should give it thought."