I write this while sipping on an espresso lemonade at Kalei, a local coffee shop in Hamra. It’s an unlikely combination, but two Lebanese journalists I met at a bar recommended the citrusy caffeinated beverage, so I figured I had to try it. Needless to say, it did not disappoint! And most importantly, the cafe has steady Wi-Fi and an outdoor garden, a nice escape from the heat and stickiness of a Beirut summer.

As I near the halfway point of my reporting in Beirut, I find myself reflecting on what I have learned about Lebanon thus far. The locals have taught me that Lebanon is a place of contradiction. Running along the Corniche in the mornings, I witnessed firsthand the glitzy 5-Star hotels, yacht clubs, and eateries that line Zaitunay Bay, the ritzy promenade run in large part by Solidere, a controversial corporate giant founded by former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

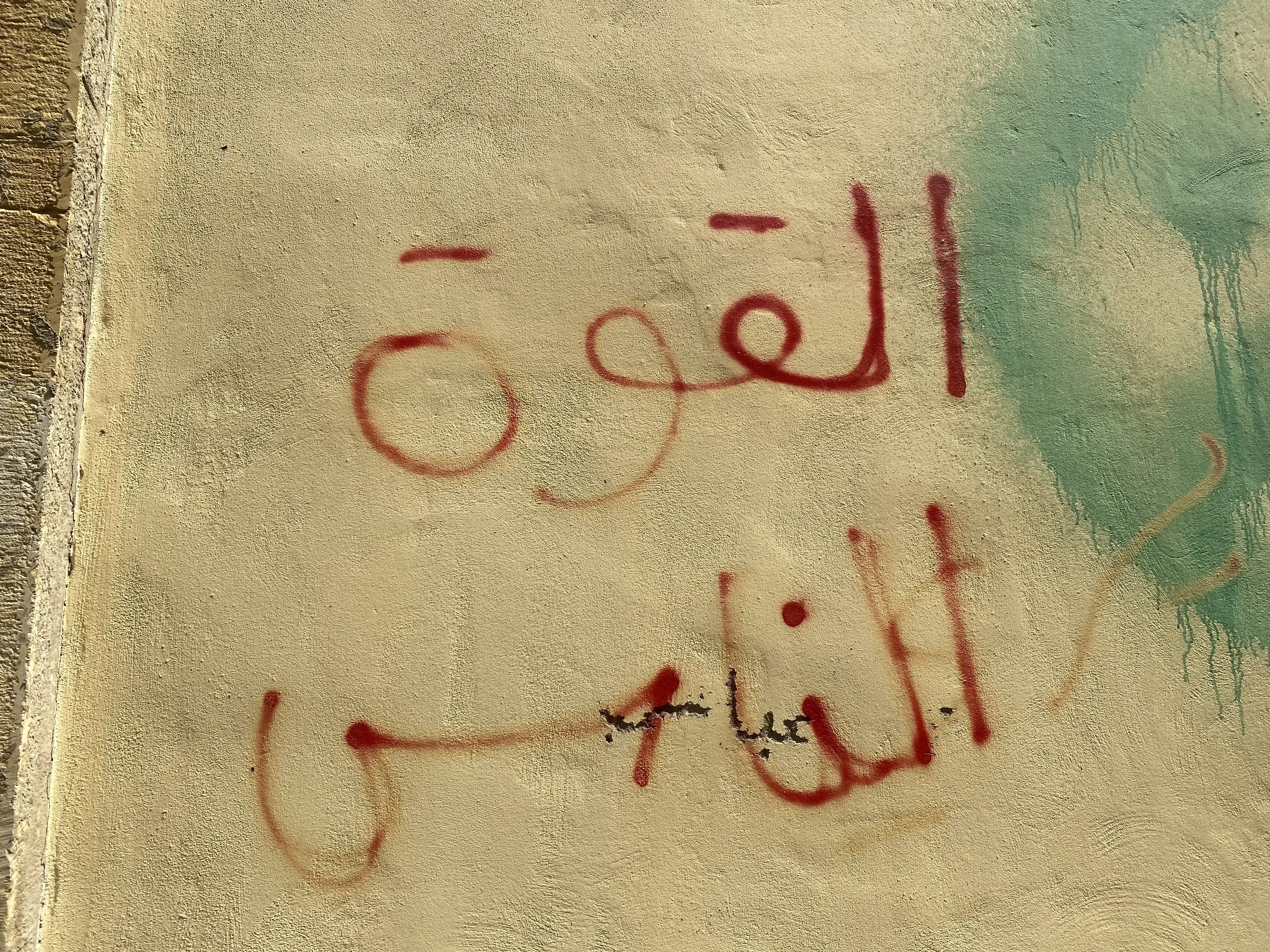

But the hotels are all closed, the sleek high-rises halted mid-construction and frozen in time, the cafes abandoned or destroyed. Following the October 2019 revolution (a series of protests in Beirut, spurred by proposed taxes on everything from WhatsApp to gas, which rebuked the government as both corrupt and complicit in Lebanon’s twin financial and environmental crises), the Beirut Blast (the largest nonnuclear explosion in history), Lebanon’s financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic, downtown was essentially shut down. The Four Seasons closed; the once-bustling restaurants shut their doors if not already destroyed; the construction halted. Some establishments prepared to reopen following the Revolution and the ongoing pandemic only to be destroyed by the Blast and the worsening financial crisis. Downtown felt like a ghost town, nearly empty save for those headed to the Al-Amin Mosque to pray or en route to luxury shops. Indeed, as my tour guide Karim explained, only the designer shops can afford to stay open.

Yet Beirut, at the same time, is bustling. The streets of Hamra, the nightclubs of Mar Mikhael, and the malls of Achrafieh are filled with Beirutis and brimming with life. Beirut is in pain, filled with the hurt inflicted by corruption, the financial crisis, the garbage crisis, and the explosion, but it is also filled with singers, filmmakers, and artists. To paraphrase a few filmmakers I spoke to, it is experiencing both creativity and apocalypse, hope and despair, joy and sorrow. These contradictions are everywhere in Beirut. Lebanon was recently ranked the second saddest country in the world, yet watching young Beirutis twirl in summer dresses at the Hamra resto-pub Mezyan and teenagers laughing over mint lemonades under string lights at the city’s many outdoor cafes, the moments of joy amidst crisis were deeply palpable. Despite the trifecta of crises facing the city, people, though sometimes disillusioned, still refuse to become bitter and hold fast to art.

Feminism in Lebanon is rife with these contradictions too. As a young Beiruti poet told me, women in Beirut can, for the most part, dress however they want, express their opinions, and make films without censorship. Yet at the same time, per the personal status laws, they lack universal civil rights and are bound legally by conservative sectarian laws. Additionally, Lebanese women are unable to confer nationality rights to their children, who are left without citizenship and in many cases, stateless. Adultery is a crime in Lebanon, though to date, only women have been incarcerated for it according to Zeina Daccache, an actress, therapist, and filmmaker who choreographs plays within Lebanese prisons, including Baabda Women’s Prison. Indeed, sect-specific religious courts entirely govern women’s personal status laws, all of which discriminate against women.

In many ways, contradiction defines life in modern Lebanon. Crisis and art, freedom and discrimination, and hope and despair all coexist. I’ve found myself returning to the question: What is the role of art in times of crisis? And what does it mean to live in a state of constant contradiction? Of course, contradiction isn’t unique to the Lebanese experience, but as I have to come to learn, it is inextricable from it. As the silos burn, the dancing girls still twirl.