Some days, Farzenah Hosseini dreads the moment the Greek government will make a decision on her asylum application.

The 21-year-old from Bamyan, Afghanistan, sees her sister Fatimah’s struggles. Granted asylum in June 2019, Fatimah lives in a tent in a refugee camp an hour-and-a-half outside Athens with her husband and four children.

Fatimah received help from camp officials for a few months after she was granted asylum, but that assistance soon stopped. The 29-year-old now relies on others waiting for their asylum decisions, like Farzenah, for food and money in order to survive.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund more than 170 reporting projects every year on critical global and local issues. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

“It’s the worst thing that you can imagine,” Farzenah says of her sister’s situation. “I don’t want to get a positive decision [on asylum] because… they are going to send me out of the program.”

“I don’t know how to survive,” she adds, noting her family belongs to the Hazara community, an ethnic group long persecuted in Afghanistan by the Taliban. They had no choice, she says, but to leave.

Thousands of refugees who have been granted asylum in Greece have been left to navigate a new life almost completely unaided. And it’s a dilemma that more and more Afghans fleeing renewed Taliban rule in their country could experience. Afghans made up 30 percent of the asylum seekers arriving on Greek islands this year, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, and still more may come.

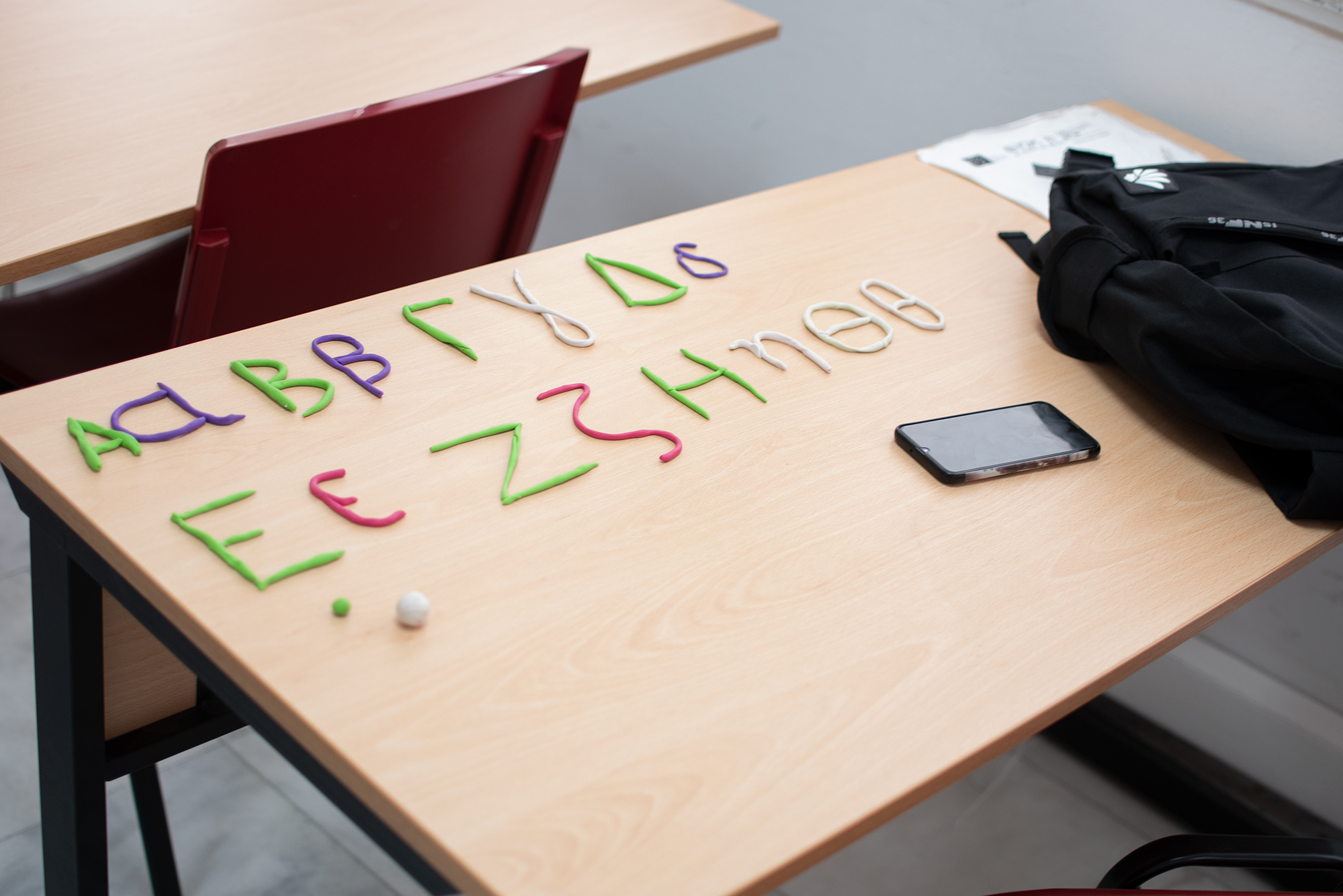

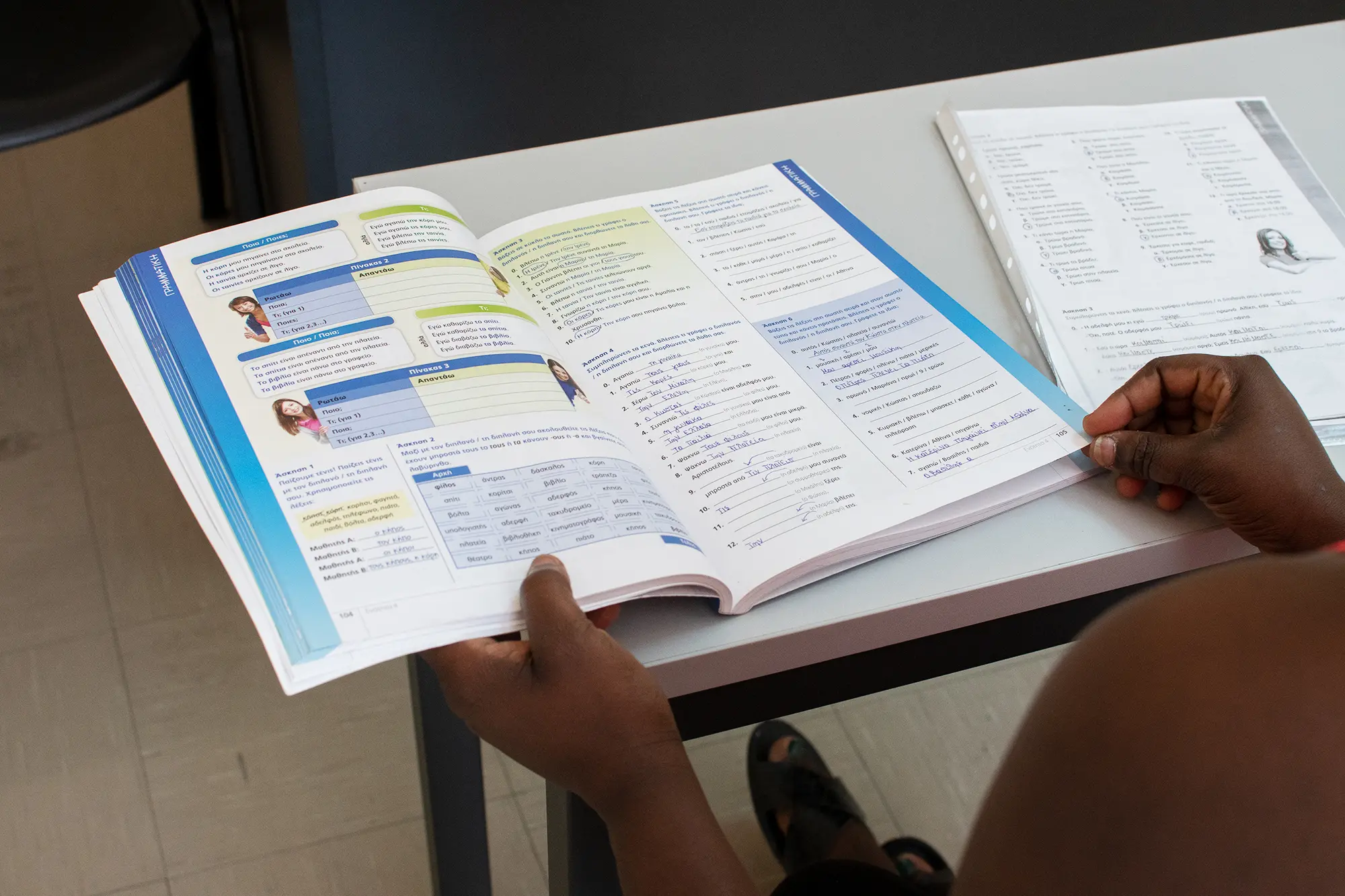

While awaiting their asylum decisions, migrants stay in camps or government-provided housing. They receive a cash card and food and have access to basic medical facilities, often provided by aid groups. In some cases, children can attend school classes, and adults have limited language-learning opportunities.

Once granted asylum, however, nearly all support stops. Recognised refugees no longer receive cash assistance and have to find their own housing and become almost completely independent in just 30 days. Beyond help from non-governmental organisations, there is only one established support system for recognised refugees. That pilot program is a temporary fix, officials acknowledge, and was largely made for migrants who want to remain in Greece.

“If you are a recognised refugee, you have less benefits and guidance than if you are an asylum seeker,” says Nikos Gionakis, head of the Babel Day Centre, an organisation focused on migrants’ mental health. “To become a refugee is penalized.”

No system in Greece for integration

When hundreds of thousands of migrants began arriving in Greece in 2015, the country was unprepared and overwhelmed.

More than a million migrants entered Greece in 2015 and 2016, figures from the UN refugee agency show, and the country established reception facilities.

That initial surge slowed, but policies like the EU-Turkey deal in March 2016, which allowed Greece to return migrants arriving illegally from Turkey, led to delays in processing asylum claims and massive overcrowding in the island refugee camps.

It wasn’t until June 2019 that the International Organization for Migration, IOM, established the HELIOS program — the first and only official integration effort in the country. The program provides rental subsidies for six months to migrants who find their own apartments, as well as Greek language classes and cultural integration courses for the same time period.

A single man in the program, for example, receives 301 euros in housing aid after signing a lease agreement, another 301 euros after paying the first month’s rent and 162 euros each subsequent month, according to IOM officials in Athens. But those who receive the subsidy must complete 360 hours of lessons, including 280 hours learning the Greek language and 80 hours for Greek history and life skills.

Soliman Zadeh, a 36-year-old recognised refugee from Balkh, Afghanistan, spent a year in the Moria refugee camp on Lesbos before he enrolled in the HELIOS program this past summer. Zadeh lived most of his life in Mashhad, Iran, and came to Greece seeking asylum at the end of 2019. It took him 16 tries, he said, to get to Lesbos from Turkey by inflatable boat. He and 40 other migrants were repeatedly caught by border police and forced back to shore.

“The smuggler made us put air in the boat and had eight people carry the boat to the water and connect the motor,” Zadeh said through an interpreter in July. Zadeh didn’t know how to swim. “If something happened during the trip, I would have died,” he said.

He left Moria, a camp known for its poor conditions and overcrowding, when it burned down in September 2020. Along with other recognised refugees, he was transferred to a hotel on the mainland. But, three months later, Zadeh was told to leave the hotel. He found a house and enrolled in HELIOS, using money he saved up from his old cash cards.

“I didn’t have any other option,” Zadeh says in Farsi. “If we didn’t come to [HELIOS], how would we rent a house? That’s why we came to this program – for shelter.”

Zadeh, however, left the program after just a month. He said the required language and cultural courses, three hours a day for five days a week in Thessaloniki, were difficult to attend; they were held during time he needed to get food from a local aid group.

He wants to go to Germany, he adds, not stay in Greece.

“The situation here is very difficult,” Zadeh said through WhatsApp in mid-August. “I lost the [first] 35 years of my life because I spent time in Greece, Turkey and Iran. I have a plan to live in a country and go to work and think about my future.” He adds: “I don’t want to learn Greek.”

But some migrants call the program their only way to survive as they try to integrate into Greek society.

Khaled Ismaiel, a 53-year-old recognised refugee from Mosul, Iraq, spent more than two years in the Diavata refugee camp outside Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, before he enrolled in the HELIOS program in June 2020.

Ismaiel and his three sons, aged 20, 21 and 25, fled to Turkey in 2017 because of the activities of Islamic State, IS, in the region. The family was arrested during their three-hour walk across the border into Greece and were eventually transferred to Diavata. They were granted asylum in November 2019 but stayed in the camp for six more months before finding their own house in Thessaloniki.

[At the time, migrants were allowed to remain in accommodations and receive cash support for six months after they were granted asylum. That period was reduced to 30 days in March 2020.]

With no money and trouble finding work because they did not speak Greek – a common issue among migrants – the family’s only option was the HELIOS program, Ismaiel said.

“At that time, I didn’t have a job,” he said in July, after attending a Greek language class at one of IOM’s integrated learning centres in Thessaloniki. “How could I survive that time without any money? How could I pay for shelter?”

The HELIOS housing subsidies stopped after six months, despite Ismaiel’s request for an extension. He still takes language courses through the program and can now communicate in Greek. Two of his sons now work for their landlord, earning 20 euros a day to cover the family’s 250 euros’ rent a month.

“It is difficult,” he said, noting he often borrows money from friends. “Both of them are working, but it is still difficult.”

Living independently is ‘difficult step’

HELIOS is not the solution for all recognized refugees, both migrants and the program’s own officials say.

At least a dozen recognised refugees told Balkan Insight they opted not to enroll in the program because they didn’t want to integrate into Greek society. Others highlighted the trouble of finding an affordable place to rent – the prerequisite to entering the program.

Just 33,688 migrants have enrolled in HELIOS since the project launched in June 2019, according to data from the last week of November. That’s a small fraction of the total number of arrivals in that same period. Those who don’t enroll mostly leave the country illegally, or wait for official travel documents like passports, or remain in Greece to navigate life on their own.

“There is, on paper, a very smooth transition (into HELIOS),” says Ljubisa Vrencev, country director for Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund Deutschland, an aid agency that manages the Diavata, Katasikas, Filipiada and Doliana refugee camps in northern Greece.

There are language learning opportunities for asylum seekers in most camps, Vrencev says, and IOM workers visit the camps to talk about HELIOS. But there are “quite a lot of issues,” Vrencev notes, with recognised refugees who are “not willing or able to exit the long-term accommodation centres” despite the 30-day deadline to leave.

“Leaving the camp really means they have to find a job and live independently, which is a difficult step to make,” Vrencev says, noting that most of the migrants currently in the camps are from Afghanistan. “They decide to stay in the camp with the community they are used to… waiting for documents so they can leave Greece.”

With migrant arrivals decreasing significantly over the past few years – just over 8,000 asylum seekers arrived in 2021 – there has been a renewed focus on helping the migrants who have been granted asylum.

Gianluca Rocco, chief of mission in Greece for IOM, said one of the “main issues” with HELIOS is employability, which he called a necessary element of integration that will allow migrants to become self-sustainable.

The project is being transferred to the full control of the Greek government, Rocco notes, which will make the pilot program more stable. IOM is working with Greece’s Ministry of Migration to create employability and job placement programs, as well as an additional program for unaccompanied minors.

The new programming, Rocco says, will also focus on Greek and European values and topics like gender equality. They expect the transition of the program to be complete at the beginning of 2022.

“It’s one of the few occasions in which you can see a project that started with an emergency and then moving to becoming a stable mechanism of the state,” Rocco says.

Sofia Voultepsi, Deputy Minister of Migration and Asylum in charge of integration, in an email to Balkan Insight noted the economic crisis that has affected Greece for the past 10 years, the large migrants flows of the past six years and conflicts with Turkey over migration as some of the challenges that have impacted the country’s ability to deal with integration.

“All of this is greatly affected by the pandemic crisis,” Voultepsi says, adding of those who say Greece hasn’t done enough to help migrants integrate: “Obviously, none of this is taken into account by those who are only used to complaining, despite the fact that [they] should be aware of and share the country’s problems.”

Lesbos camp ‘was like hell’

Farzenah and Fatimah, the women from Bamyan, described living in the Moria camp on Lesbos as depressing and scary.

After a three-month journey to Greece, they spent the next seven months in a tent without electricity. The women said they often had to walk far from their makeshift home to use the bathroom, and were constantly worried for their safety.

At one point, they said, they were among a group of people attacked by men with knives. A woman’s hand was cut in the attack, Farzenah said, and police arrested the men involved. The family was transferred off the island soon after.

“It was like hell,” Farzenah recalls.

Such experiences affect the mental health of migrants, which adds to their difficulty in integrating into society, according to Gionakis, of the Babel Day Centre.

“The dominant narrative is that the people who arrive here are traumatized and they bring issues from the past and so on,” Gionakis told Balkan Insight. “But in general, we have seen that many people have to deal with everyday life challenges, and most of them are provoked by the way that we treat them when they arrive in the place where they think they will find safety, protection, security and all these things.”

“Instead of that,” he adds, “many times, they find dire conditions, with inhumane treatment, no safety, no perspectives for their future. All this, of course, affects their psychosocial well-being.”

People need to feel safe for their mental well-being to flourish, according to Gionakis. His organization, which is funded by the Greek Ministry of Health, recommends camps take steps like putting lighting in bathrooms and separating men and women’s bathrooms to try to alleviate some stress.

“We need to take into consideration the conditions under which they live,” he says, “and of course not to let them stay [in camps] for long. We know that people who stay in a place like this for long, even if they are healthy, acquire mental health issues.”

Afghans seeking asylum in Greece “are more likely to get protection than they are in many other countries,” according to researchers from the Migration Policy Institute. Asylum claims from Afghanistan might also have a better chance following the Taliban takeover, the experts say, though data on asylum decisions by country since August has not yet been released.

At the same time, Greece is taking a tougher approach to curbing immigration. Notis Mitarachi, the Minister of Migration, has called for migrants arriving illegally to be deported. In recent months, Greece has been accused of illegal pushbacks – forcing migrants attempting to arrive in Greece back to sea. The government has denied the allegations.

“We do everything in order for them not to stay here,” Gionakis says, “and those who want to come even to pass through Greece to go to other places [are told] not to come.”

‘Only hope’ is other countries

Today, Fatimah says her life is even more difficult than when she was waiting for her asylum decision. She still lives with her family in a single room in the refugee camp outside of Athens.

It has been three years since she was granted asylum, and she hasn’t received her passport. Once that comes, Fatimah said, the family will leave Greece.

Farzenah is still waiting for her asylum decision. For the past four months, she says, she hasn’t received the cash assistance she’s entitled to as an asylum seeker, which she and her sister’s family rely on.

Many asylum seekers in Greece reported not receiving the funds after the Greek government took control of the cash assistance program from UNHCR in October. Farzenah in a Facebook message in November said the family now only has money “for dry bread”.

“My only request from the government who are holding the people like this … instead of this, open the way for them to go,” Farzenah says. “Not to hold them and make them depressed, make them worse.”

“Our only hope is other countries,” she added. “Any country. Not Greece.”