Mother to two beautiful teenage daughters back in her hometown in southern India, 35-year-old Lakshmi Senthilnathan has spent over a third of her life working as a domestic worker in Oman’s port capital, Muscat. She is a thin, sprightly woman, her hands bobbing in the air as she tells stories from her remarkable life. Pushing a lock of her graying hair back into her tight braid, she speaks of her husband, an alcoholic, she says, who is unable to hold down a job.

For over a decade, the responsibility of providing for her children and aging parents has fallen entirely on Lakshmi and she’s accepted this duty with grace.

In her soft, lyrical voice she tells of the many homes she’s worked for in the Middle East, brushing over multiple incidences of sexual and physical abuse with shocking ease. When asked, she says it’s nothing new. Her very first employer sexually assaulted her. Her second employer’s wife would beat her if she took too long to finish her chores and the third stole the one piece of jewelry she owned.

“I don’t dwell on those instances,” she says, “I’d rather think about the financial comfort I have provided for my family and the education my daughters have been able to pursue.” Her older daughter hopes to be a doctor and the younger one is a talented athlete, she adds with pride.

“It could have been worse,” she says pragmatically. One of Lakshmi’s friends had all her hair shaved off by her employer for insubordination. Another has not been allowed to visit her family in five years and many more, she alleges, don’t get paid for months at a time.

For the over 2.5 million domestic workers in the Gulf countries, the majority of whom are female and hailing from Asia and Africa, Lakshmi’s stories are neither alarming nor unique. Gossip in their circles is peppered with recollections of abuse, and their threshold of acceptance is chillingly high.

Every so often, particularly disturbing cases make the news. For instance, the case of 49-year-old Ariyawathi, a Sri Lankan domestic worker in Saudi Arabia who was found to have 13 nails and 11 needles hammered into her body by her employers, and that of Kasthuri Munirathinam, a 58-year-old Tamilian who had her right arm cut off for complaining about working conditions, were unnerving enough to garner strong mainstream media attention. When the body of Joanna Demafelis, a Filipina domestic worker, was found in a freezer in Kuwait, the Philippine government responded with heated criticism.

While these severe incidents receive the attention they rightly deserve, the daily occurrences of relatively lesser misdemeanors rarely come to light. Thousands of women across the region will face abuse today but remain obscured behind layers of socio-economic imbalances.

There is no one single law, organization, or cultural practice to which such normalized discrimination can be attributed. The responsibility is distributed among an archaic ecosystem of multiple stakeholders who each battle distinct issues.

Foremost is the negative consequence of untethered globalization. A free market imbalance where the supply of blue-collar workers from South and Southeast Asia vying for relatively higher paying working-class jobs far exceeds the demand from the countries of the GCC—the Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia)—pushes down wage rates and deteriorates working conditions.

Often uneducated and burdened with familial responsibility and debt, migrant laborers find that in the majority of cases they are able to earn more in the GCC than what they could have in their home countries. For instance, a refuse worker in India would earn an average wage of $45 per month, while the same refuse worker in Kuwait could make up to $560 per month. Such drastic differences in wage rates can push these resilient women to be extraordinarily tolerant in the face of regular strife, thus making them easy targets for exploitation.

From as early as 1996, the International Labor Organization has expressed continual worries that a ‘buyer’s market’ in the Middle East would put a “downward pressure” on conditions of work for low-income migrant workers.

“If I had gone back home at the first sign of trouble, I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish any of this,” attests Lakshmi, “I stayed because I knew it was my one opportunity to create a better future for my family.” Since domestic workers like Lakshmi are willing to work in poor conditions and weather systemic abuse, an unspoken culture of exploitation is allowed to prevail behind closed walls.

The negative effects of this economic disparity have been further exacerbated by a prevalent GCC immigration program that perpetuates the unjust culture—the kafala system. The system necessitates that all migrant workers have an in-country ‘sponsor’, typically their employer, who is given an inordinate amount of control over their legal status. The sponsor assumes responsibility for their employee and the worker needs their explicit written consent to change jobs, and in some cases even enter or exit the country. Such a directive intrinsically leaves the workers extremely vulnerable to mistreatment, giving employers the ability to hold them against their will and force onto them extreme and abusive labor conditions. Human Rights Watch reported that the system “made some employers feel entitled to exert ‘ownership’ over a domestic worker,” and it is repeatedly emphasized by blue-collar immigrant workers as a severe limitation of their freedom and liberties.

“[The sponsors] take our passports the minute we enter the country,” says Jameela, a 45-year-old domestic worker who wished to only be addressed by her first name, “and they tell us that if we do not follow orders they will not give it back to us.”

Countries such as Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar have taken some steps to repeal parts of this antiquated system. For instance, following heavy criticism of the labor conditions faced by construction workers building the 2022 FIFA World Cup stadiums, Qatar has put forth a new minimum wage for migrants of 750 Qatari Rials (around $250 USD) per month, and vowed to gradually dismantle the kafala system by working with the International Labor Organization. The extent to which such legal mandates have translated into daily practice in society, however, remains to be measured. The negative effects of the kafala system’s legacy unfortunately are largely immune to surface level regulatory changes and need a much higher level of cultural penetration to create real behavioral change.

While we look to the GCC governments to enforce reasonable working conditions and restructure the immigration system, social workers and NGOs also point to shortcomings in the stop-gap policies implemented by the governments of the home countries to ameliorate the situation for their citizens working abroad.

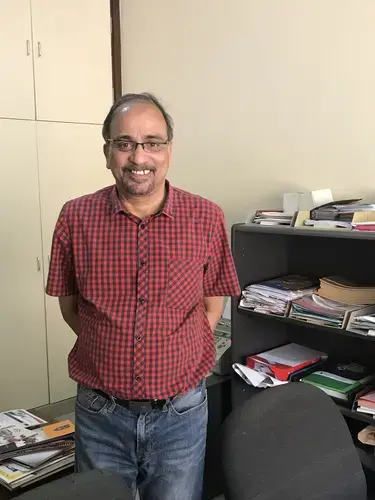

Earlier this summer in Oman, 38-year-old Sheeja Das jumped from the second-floor balcony of the house she worked in to escape her employer’s beatings. The fall left her paralyzed below the waist and consequently she was sent back to her home town in Kerala, India, allegedly without any compensation. PM Jabir, a prominent social worker specializing in issues related to Indian blue-collar workers, helped secure airfare and safe passage for Das and her husband. Jabir is a charming middle-aged man who has assumed the role of mentor and advocate for tens of thousands of migrant workers through the last few decades from 1989. “My biggest contribution is inspiring other people to take up this cause,” he says proudly, “When I started, there was no one I could follow.”

Jabir runs the Non-Resident Indian welfare fund, manages a network of volunteers for medical and legal camps, has helped repatriate over 4,000 deceased workers, and spends at least two to three hours at the Indian embassy each day to expedite bureaucratic procedures. Every five minutes, the ringing of his phone punctuates his passionate anecdotes. He attends each call patiently, his calm demeanor at odds with the anxious voices on the line. Jabir believes that so many people would not need to come to him for help if public institutions were able to provide adequate and timely support. “[These people] should have been helped even without my involvement,” he stresses.

While Jabir acknowledges that both the Indian and Omani governments have created laws that “favor the worker,” he also is critical of the lack of dedicated human resources on both sides that has severely crippled the grassroots level implementation of the systems and regulations that have been theorized.

The Madad online portal, for example, was set up in 2015 by the Indian government to address the grievances of Indians working or studying outside the country. Officials monitoring the complaints have a set time within which they are required to respond to the complainant or be subject to an investigation on the cause of delay. This stipulation was intended to guard against overdue responses caused by backlogs in the system and ensure that no issue was overlooked.

Petitioners and social workers, however, allege that instead the system incentivizes overworked or unmotivated administrators to give superficial answers that do little to mitigate the actual problems. “We got replies, not solutions,” says Savita, a young domestic worker who is now waiting for her case to be heard.

Savita’s story brings to light another key set of players in this complex network that worsen workers conditions—illegal recruitment agencies.

She has worked in Muscat for over nine years under what she calls the ‘free visa’ program. She pays her Omani sponsor 200 OMR a month (520 USD) in exchange for providing her with a work visa. She cleans and cooks for five households in the neighborhood and shares an apartment with four other such women.

Under the kafala system, this type of employment is unlawful. However, Savita says that until her sponsor began extorting her for higher fees and threatened to have her deported, she was not aware that her actions were illegal. As in the case of Savita, unconfirmed estimates put hundreds of thousands of workers in the GCC, knowingly or unknowingly, operating illegally under the ‘free visa’ structure. While it gives workers more freedom in choosing employers, it also leaves them completely unprotected by the law and thus much more vulnerable to exploitation. “I remained silent for months because I knew that if I complained about my sponsor, [the authorities] would find out I was working illegally and deport me.”

Savita’s story, like that of most of the Middle-East’s illegal workers, starts thousands of miles away, in her home country. Persuaded by false promises of high wages and luxurious lifestyles, people often fall prey to informal recruiting agencies across South Asia that secure illegal or fabricated employment for the prospective workers in exchange for a hefty fee.

Indra Mani Pandey, the Ambassador of India to Oman, contends that much of the progressive steps taken by the External Affairs Ministries is undermined by the continued existence of such agencies who constantly evolve their methods to “circumvent due procedure.”

For instance, when the embassy in Oman instituted a 1,000 Omani Rial bank guarantee requirement for Indian domestic workers from their employers, as a security deposit against unpaid wages or other compensation needs, the agencies began to traffic the workers into the country through its border with the United Arab Emirates.

According to Pandey, the embassy currently has one full staff member monitoring the Madad portal. A special tribunal set up by the Omani government addresses legal cases that are not resolved in the first few months by a settlements court, and a lot of work has been undertaken to rehabilitate returning immigrants and provide them with financial and legal support back in India. All these efforts fall regrettably short as long as ‘free visa’ providers and illegitimate recruiting agencies essentially keep afloat a black market of laborers who cannot be directly and efficiently targeted by the governments.

The future of low-income Indian expatriates to the GCC, in Pandey’s eyes, does not lie in a complete redesign of the immigration structures or in a cultural transformation that denounces discrimination. He believes that the path forward involves transitioning poor Indians away from unskilled labor and into skilled opportunities that are more lucrative and less risky. The Indian government, he says, is “placing an emphasis on the technologies [needed] to train people adequately” for the advent of the fourth industrial revolution.

Around 8.3 million immigrants from the GCC send back an estimated $65.5 billion annually to India, accounting for over 50 percent of total global remittances to the nation. The role of the Middle East in supporting India’s poor cannot be ignored. The Indian labor force, meanwhile, has given unparalleled contributions to the GCC’s economic development especially in the last two decades.

The positive impacts of this symbiotic relationship between the home and host countries of migrant workers, however, are marred by the grisly details of discrimination and exploitation that happen behind closed walls and in informal markets. Is this progress worth the price?

Given how deep and wide the multifaceted systemic problem runs, it is no one issue but an entire ecosystem that needs reform. From cushioning the consequences of globalization with stronger enforcement of working standards to redesigning the kafala system, from purging illegal recruitment agencies to rehabilitating exploited workers upon their return, governments on both sides have a challenging path ahead of them.

For Lakshmi, however, the future is optimistic. “I’ve saved enough money to construct my own house,” she says happily, “and I’m ready to retire once the grandkids come.”

(All the names of the domestic workers mentioned in this article have been changed to protect the anonymity of the interviewees.)