On an overcast winter morning in Bridges Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., Joseph Egan, 33, was sitting in the back of a kindergarten classroom, busily jotting down notes. It was the first full school week after the 2018 New Year, and students were gradually recovering from the holidays.

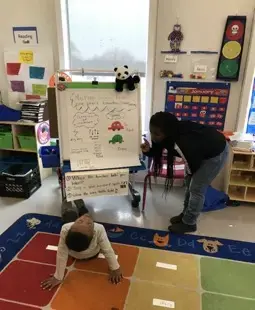

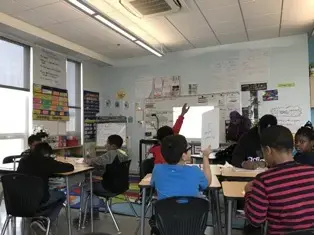

“What does the motion of a seesaw look like? Up and down or back and forth?” Assistant teacher Jezel Kelly asked the class. Some students immediately raised their hands, while a few sat still and gazed at the teacher blankly.

Observing this, Egan quietly stopped his writing and came forward to one of the children that didn’t respond to the question, a boy with a crop haircut and big black eyes. Egan murmured to him something in Spanish. Immediately, the boy’s frown relaxed. When Egan returned to his seat, the boy raised his hand, though still a little hesitantly.

Egan is not a kindergarten teacher. His students range from kindergarten to fifth grade, come from different cultural backgrounds, and speak more than one language. He is the English Language Learner (ELL) Coordinator and teacher at Bridges, and all his students are English Learners (ELs), including the boy he talked with in Spanish in Kelly’s class.

The District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) defines an EL student as a linguistically and culturally diverse student who has an overall English Language proficiency level of 1 to 4 on an English language test administered each year (the highest level 7 is used for students who are native English speakers or who have never been designated as EL). Any EL has the chance to test out of the system once his English proficiency has scored 5 or above. According to the Department of Education, more than 75 percent of ELs are Hispanic or Latino.

In Kelly’s kindergarten classroom, two out of every five students are ELs, a bit higher than the school’s average of 35.70 percent. That means 140 out of over 6,000 ELs in D.C. public schools (including public charter schools) are in Bridges.

The most recent data from the Migration Policy Institute’s ELL Information Center shows that there are around 5 million ELs across the United States; one out of every 10 students in public school. This large and growing number of ELs has raised a serious issue: teacher shortage.

“At Bridges, we have about 140 students, but only one and a half EL teachers. It’s a lot. There’s not enough resources, and there’s way too many students to focus on,” said Egan. “One and a half” refers to Egan himself and Ashley Geohaghan, the other EL teacher at Bridges.

As the ELL coordinator and one of the few teachers at Bridges who can speak fluent Spanish, Egan has to do much extra work, such as parent outreach, helping translating school letters into Spanish for parents who cannot read in English, and teaching Spanish Take Aim And Grow (TAAG) program, an after-school program started by Egan in 2016 that aims to teach top performing ELs elementary to intermediate Spanish.

“I don’t have as much time as I wanted to teach these kids, so I’m only counted as half,” Egan laughed as he explained.

Such a skewed teacher to student ratio of 1 to 100 for ELs is not a rare thing among D.C. public schools. Arthur Mola, the principle of Bancroft Elementary School at Sharpe said that the demands on their EL teaching staff was “at an all-time high.”

The EL teacher shortage, as mentioned by Egan and Mola, has become a rising issue not only in D.C., but across the whole country. In the most recent Teacher Shortage Areas Nationwide report published by U.S. Department of Education in June 2017, 33 out of 50 states reported not having enough teachers for EL students. Since 2013, around 30 states have reported the EL or Dual Language Education teacher shortage every year, whereas in 2003, only 14 schools did so. The report also highlights the current top two high–need fields in schools that serve low–income students: Bilingual Education and English Language Acquisition, two areas that are considered to have a significant impact on EL’s academic achievement by educators and scholars.

Among the many possible factors that could cause the teacher shortage, the conflict between the influx of non-English speakers and the extra training required for EL teachers is a big one.

“We know there is a rapid increase of EL population, but very few teachers, less than 13 percent, have received training and support to serve ELs in classroom successfully,” said Marguerite Lukes, director of Research and Innovation at Internationals Network for Public Schools, Inc, an educational nonprofit serving newly arrived immigrants who are ELs in New York.

Even if teachers are bilingual or biliterate, according to José L. Medina, director of dual language and bilingual education at the Center for Applied Linguistics, it does not mean they know how to teach English language literacy to ELs.

Egan has been working with ELs for eight years. Before coming to Bridges, he earned a Master of Education in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, and served as the EL teacher and curriculum developer in various educational institutions. Standing in the school corridor, when asked why he chose to be a language teacher, Egan patted the shoulder of a boy who came to hug him and smiled. “I myself enjoy learning different languages, it’s challenging but a lot of fun. These kids have many potentials, and I want to see them thrive here.”

Another explanation for the teacher shortage is money.

“The biggest challenge is the lack of funding overall. Last year we received around $67,500 through Title III. This is not even enough to pay for both of our full time teachers,” said Egan.

Title III is the name of the funding specially designed for ELs. From a report by Office of the State Superintendent of Education in DC, in 2017-18 school year, the foundational level per pupil funding is $9,972. The allocation for ELs is $4,887, with the weighting of 0.49, lower than the recommended 0.61; the weighting for special education ranges from 0.97 to 3.49, and for general education 1.00 to 1.34. That means the funding for ELs is less than half of special education or general education.

According to Egan, the funding gap shows why in a special education classroom it is typical to see five teachers with five to 10 students, while he is in charge of more than 100 students by himself.

The lack of money also indirectly leads to the previous problem, the insufficient training for EL teachers. The data in Office of the State Superintendent shows that some schools in D.C. skip EL services altogether, and just train general education teachers for EL teaching.

On the other hand, from an administrator’s perspective, José Medina, who before coming to Center for Applied Linguistics, has served as a school principal and director of EL Education in district level in Texas, said that despite the limitation of funding, educators can find creative ways to ensure that students’ needs are met.

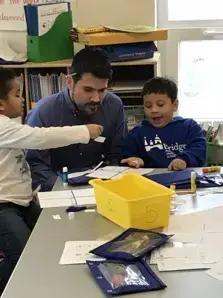

When Egan is not in the classroom helping students, he spends most of time developing teaching plans and analyzing student reports. But on his way between classrooms and his office, there are always students coming to him to say hello.

One recent afternoon, a third grade girl asked him to repair her broken hair pin, and a second grade boy clung to him, wanting to spend more time with him. Sophia, a second grade girl asked, “Mr. Joseph, can you give me more books about princess?” Egan laughed warmly and assured her, “Of course, of course, Sophia. Did you finish all the books I gave you?”

Egan knows almost every students’ name at Bridges, and he always says their names with a smile.

Egan also uses his own money to buy books for these children.

“We have a book program for students to read at home. A lot what we see is that they don’t have a lot of resources at home, so we’ve been supplying them books before they went for winter breaks. We bought them a bunch of books and gave to them, and it seems to help,” he said, after promising Sophia that she would have more books if she liked.

At Bridges, 67.40 percent of students are economically disadvantaged, and qualified to have free breakfast and lunch at school.

“Reading is not a popular habit among those households, where many parents were too busy at working to even talk to their children, let alone encouraging them to read,” said Egan with a sigh. “Socio-economic status is a significant factor determining students’ academic performance, and this is particularly pronounced among English Learners.”

Indeed, in a reading performance report released by National Center for Education Statistics, in 2015, the achievement gap between non-EL and EL students is 37 points at the fourth grade level, and the achievement gap between students at high-poverty schools and low-poverty schools is 36 points at grade four. Both results are consistent with the results from previous years.

In English Language Teaching, scholars and educators have differentiated two schooling models: subtractive and additive. According to Angela Valenzuela, professor of Educational Policy in the University of Texas at Austin, in the subtractive framework, teachers subtract resources from ELs, divesting them of their cultures, languages, and community-based identities; in an additive schooling model, however, educators are purposeful about establishing authentic caring relationships with their students.

Most public schools in the United States today are structured on the subtractive model, trying to bring all students into an English system. At Bridges, all students communicate with each other in English, and ELs are no exceptions, even if they understand their native languages better.

But in recent years, there emerges a relatively new teaching practice to serve ELs: dual language program. Different from traditional teaching approaches that only emphasize English literacy, the dual language program aims to strengthen ELs’ home languages alongside English.

“It happens every day in the United States that English Learners are forced to erase their language and erase their culture, so as to fit into this English-only environment,” said Medina, of the Center for Applied Linguistics. As a result, most of the programs that his organization offers to support the needs of English Learners are still subtractive in nature, because they don’t focus on valuing the native language and culture as a resource. “In many cases it’s still about transitioning kids into English,” he said.

Eight D.C. public charter schools have dual language programs, and most of them are in Spanish and English. That means among 118 public charter schools, they make up less than seven percent. Bridges is not bilingual, but Egan is doing the best he can to teach his students the appreciation of their native languages.

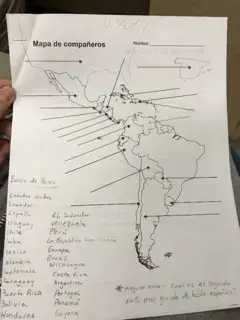

Since most ELs’ home language is Spanish, staring from 2016, Egan initiated a Spanish afterschool program. It focuses on more than learning the language, but studying Spanish speaking countries’ culture and geography. However, because Egan is the only teacher in charge of the program, and because of the strong emphasis on English language performance and the financial restraint, the amount of time that students are exposed to Spanish, and the number of students who are in the program is limited: four students are in the program at present, and they meet once a week, one hour each time.

Elizabeth, a fourth grade girl in the Spanish program, said she loved this class and looked forward to it every Wednesday: “It helps me know more about my native culture and communicate with my parents better.”

However, without additional support, it is hard for ELs, especially at an young age, to navigate two languages at the same time. This is is why Egan said knowing more than one language, supposedly a plus, becomes a deficit for his students, because most of them can neither speak English well, nor their native tongues well.

“The only way we can truly eliminate the achievement gap, specifically for language learners, is to really strengthen their native language, because by doing so, we also empower them to other languages so that students can apply them as well.” Having served ELs his whole educational career, Medina said that to fully meet EL students’ need, dual language is the only additive module to serve emerging dual language learners.

In the 90s, ELs were often regarded as slow and stupid, and as the object of ridicule due to their limited English proficiency. In recent years, though, educators have realized it was not the EL’s fault to appear tired and disengaged during the class. Nevertheless, it is hard to put recognition into practice, and developing an effective instructional design that truly meets ELs’ needs is still a challenge for teachers.

“It’s difficult for teachers to just engage students who are invisible and overlooked, because the instruction simply does not reach them,” said Marguerite Lukes, director of Research and Innovation at Internationals Network for Public Schools, Inc.

At a fourth grade math class, Mauro from Mexico was sitting with two other ELLs at the front row, far left. They were learning divisions, and the teacher, who was new to Bridges, was instructing them to write down their working process on a whiteboard and raise their board if they have finished.

Whereas students at other tables enthusiastically raised their hands one minute later, Mauro was lying his head on the desk as if sleeping, and the other two students stared at each blankly, looking totally confused and lost. Not once did they raise their boards, nor write down any numbers.

The teacher didn’t pay much attention to them in the first 20 minutes, but in the middle of the class, she asked some class volunteers to sit with Mauro and the other two ELLs. Mauro sat straight finally. But most time, when the girl sitting next to him tried to talk with him, he only gave her a shyly smile and said nothing. By the end of the class, he hadn’t finished a single math problem by himself.

What teachers can do is on one hand, and what parents can do is another. Students spend half of time with their parents, and a conductive learning environment at home is crucial to a student’s, especially an EL’s successful academic performance.

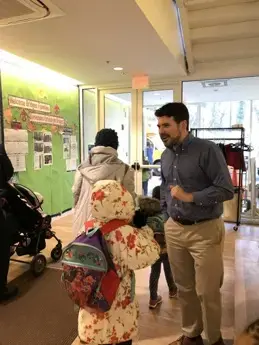

Therefore, in order to encourage parental involvement, Egan and his colleagues initiate an Afterschool Homework Program, inviting parents to come to school and study with their children every Wednesday after the school dismissal. Thanks to his fluent Spanish, Egan can work as an interpreter for parents who understand little English to communicate with other teachers.

3:30 pm is when school ends at Bridges, and parents were waiting outside to pick up their children. Egan was standing at the doorway, smiling his warm smile, greeting some parents in Spanish and waving goodbye to child passing by. “You did a great Job today, Michael!...See you tomorrow, Elizabeth!...” He called every students’ name accurately, looking not a bit of tired even after more than seven hours’ work. The students are also waving back to him, “Bye Mr. Joseph! See you Mr. Joseph! Thank you Mr. Joseph!...”

Egan has a reason to stand by the door, beyond building relationships with students. “I stand there every day after school so that if parents have any problem, they can directly find me here without the trouble of going to my office,” he said.

“Mr. Joseph is just incredible.” More than one teacher at Bridges described Egan’s passion for ELs.

Despite many difficulties lying ahead, Egan is grateful and optimistic. “Though we are still short of teachers, and many English Learners are still lagging behind, compared to 30 years ago, we have made vast improvements and will continue to do so. Slowly but surely, we are working to become more important.”