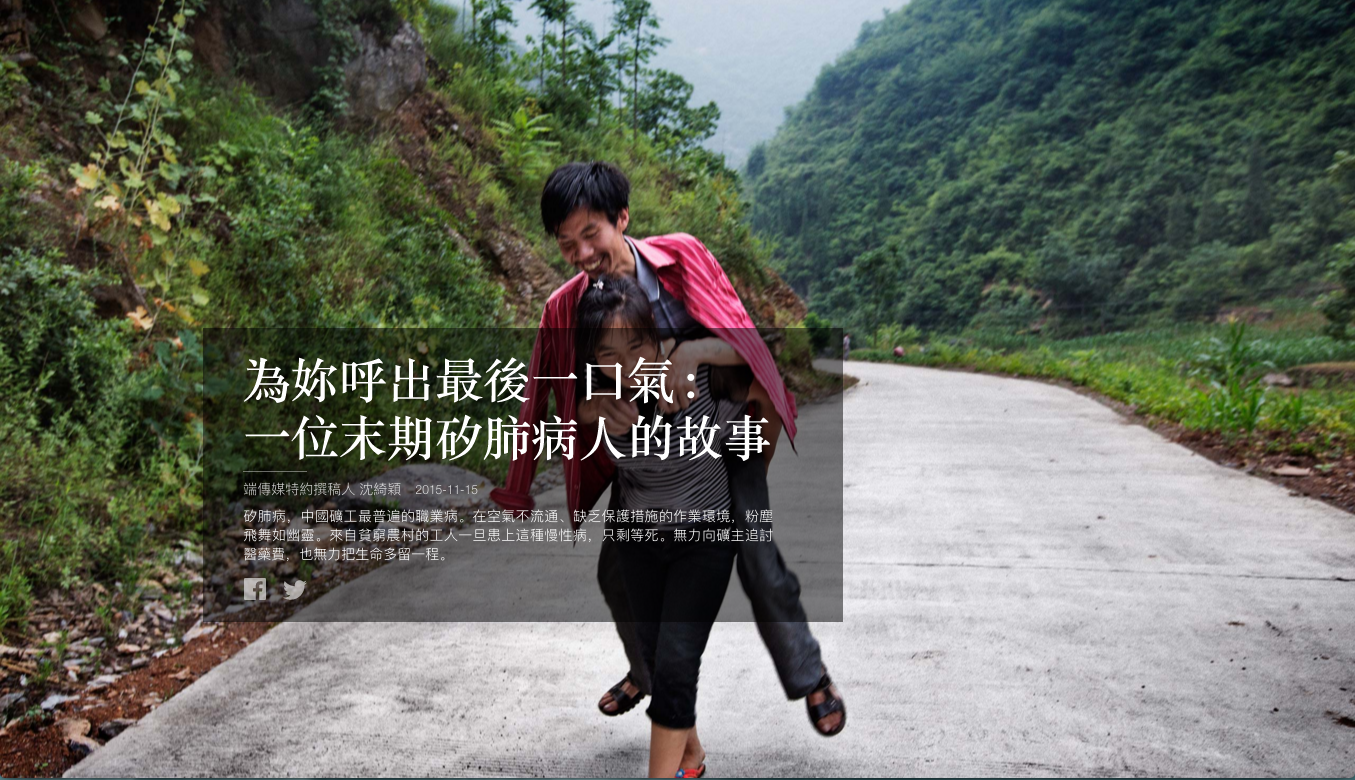

A coffin sits in a corner of He Quangui's house.

He has kept it stubbornly shrouded. But a hacking cough reminds the former gold miner of his mortality.

It's been nine years since He was diagnosed with silicosis, a form of pneumoconiosis in which a worker's lungs are overwhelmed by the dust breathed in years earlier while working in gold, coal or silver mines. It is China's number one occupational disease.

He is typical among victims: in his 30s, a sole breadwinner, a migrant worker from a remote, poor village, and facing an uphill trek getting treatment with little money and paltry employment paperwork.

Silicosis is irreversible and there is no cure. It starts to sicken workers some 10 years after they worked in dust-filled mines. Experts say those who worked in gold mines get sick quicker and also die sooner than other "black lung" sufferers. Gold miners fall ill within months of contact with the dust.

Common in the United States in the Depression era, silicosis—a fully preventable disease—is now rarely a problem in the developed world. But in China, reported cases of pneumoconiosis have increased in recent years, part of the human cost of the country's breakneck pace of development and resource extraction over the past 30 years, and persisting social inequity and weak legal system.

About 6 million people in China have pneumoconiosis, according to a local NGO.

Once they are ill, these men find it very difficult to get help, both legal and medical. Often, they are simply sitting in their village homes, tucked away in the mountains, helpless.

This is a portrait of former gold miners, waiting for death.

-

×

English

English