This lesson was created by Arizona State University professors Amanda R. Tachine (Diné), Ph.D., Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy (Lumbee), Ph.D., and K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke/Creek Nation, not enrolled), Ph.D. It was originally designed for facilitation with undergraduate and graduate students, but has been adapted to be facilitated for secondary and post-secondary classrooms. Click here for a blog written by Professor Tachine and her former students Brody Frieden and Jaimi Foster about their experiences engaging with the lesson in 2022.

Objectives:

Students will be able to...

- Analyze the key details and central ideas of texts about the history and lasting effects of the Morrill Act of 1862 on Native communities in the U.S.

- Acknowledge that universities and the U.S. are built on Native homelands.

- Recognize American Indian/Native American presence in 21st century U.S.

- Conduct research on the wealth earned as a result of land grants to universities, and the histories and cultures of American Indian/Native American tribes whose land was taken and distributed as a result of the Morrill Act of 1862.

- Brainstorm recommendations for ways in which colleges and universities that have benefitted from the Morrill Act can utilize the wealth earned from land grants to support the American Indian/Native American tribes who had previously owned the land they were granted.

Lesson Overview:

Students will learn how to distinguish between land, property, and place in a higher education context. Students will also reflect on their own “sense of place” or “sense of belonging” as they explore resources about Native expressions of place and belonging, and make connections.

This lesson is designed for mixed classrooms that include U.S. citizens / residents and international students, who are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. The lesson was written with the assumption that few classes will have a majority of Indigenous students, and that for many students the content of this lesson might be unfamiliar. The two learning objectives focus on American Indian peoples and lands in the U.S., while the in-class discussion activity associated with this lesson calls for students to reflect on their own sense of rootedness in place or sense of belonging. The lesson design is based on pedagogical theory that authentic engagement with the experiences of “others” or “other cultures” requires us to reflect on our own culture and experiences. Self-reflection provides a necessary foundation for critical understanding of others, and comparative analysis of diverse cultural and historical perspectives.

Background:

Colleges and universities are situated in regions with particular heritages, cultures, and aspirations, and scholars at these institutions are uniquely positioned to address the problems of their regions, and to offer perspective on the distinct historical, cultural, social, demographic, political, economic, and environmental forces shaping these regions. A focus on place means learning from local knowledge, as well as understanding the (inter)connections and divergences between land, property, and place. If an institution is socially embedded, meaningful and productive relationships between the university and its surrounding community, region, and state will flourish. Not least among these is the role of the university as a primary driver for regional social change, social and cultural learning, inclusion, and appropriate economic development.

Pre-class Assignment:

- Review the following resources:

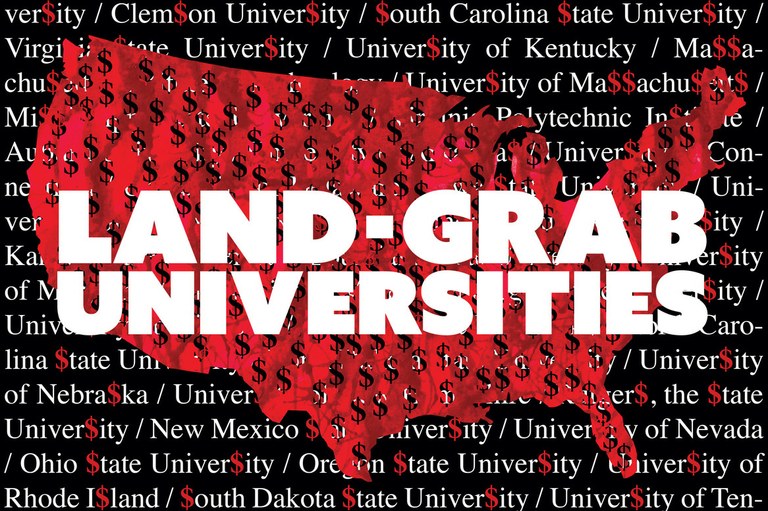

- “Land-Grab Universities” by Tristan Ahtone and Robert Lee for High Country News

- Nash, M. A. (2019). Entangled Pasts: Land-grant colleges and American Indian dispossession. History of Educational Quarterly, 59(4), 437-467.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., & Tachine, A. R. (2021). Myths, erasure and violence: The immoral triad of the Morrill Act, Native American and Indigenous Studies, 8(1), 149-144.

- Brayboy, B. M. J. & Lomawaima, T. K. (2018). Why don’t more Indians do better in school? The battle between U.S. schooling and American Indian/Alaska Native education, Daedalus, 147(2), 82-94.

- Bring to class a photograph, image, item of memorabilia, song … some tangible object that:

- connects you to a place;

- reinforces a sense of belonging;

- enhances your sense of identity.

Prepare to speak briefly (1 minute!) describing and explaining how your item expresses or symbolizes your sense of connection.

Caution:

We purposefully use the term “place” because it resonates with the language used in Arizona State University’s design imperatives. We avoid use of the term “home” when referring to a sense of rootedness or belonging because not all students have a “home” in the sense the term is often used. Some students might be homeless, or estranged from family, or have documented or undocumented immigrant or refugee status—a number of thorny and emotional issues might attach to the term “home” more strongly than the term “place.”

This module is intended to encourage all students, of all backgrounds, to think carefully about:

- what place does or might mean to them;

- the fact that in the U.S. all places were and are Native places.

We do not intend to encourage students to think that everyone can or should claim Indigeneity; or that non-Native claims to place are “the same as” (or superior to) Indigenous claims to place.

Warm-up:

- Students present and describe an item that expresses their sense of connection to place or belonging, or that expresses their sense of identity or self.

- After all students have presented their item, ask students to share overarching themes of place and belonging identified among their peers, which provides a glimpse into the classroom’s sense of connection to place(s) and belonging. What connections did they notice between what objects students selected and why?

Introducing the Lesson:

1. Show two videos produced at Arizona State University (ASU): ASU 101 - Leveraging our Place and ASU Indigenous Land Acknowledgement to class and ask students to take note of how Native students in the videos are describing place and belonging at ASU.

- Note: Videos include welcome remarks from Arizona State University President Michael Crow that draw on the design aspirations of the New American University, and the statement of “ASU Commitment to American Indian Tribes’ that recognizes that ASU resides on the homelands of Native peoples, including the Pee Posh (Maricopa) and Akimel O’odham (Pima). Arizona is home to 22 Native nations, exercising jurisdiction over approximately one-third of the state’s land base. Paul Chaat Smith, (Comanche) “Lost in Translation,” Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), is also adapted in the ASU 101 - Leaving our Place video to remind us that everyplace in the U.S. was and is a Native place. These videos provide an opportunity to listen to Native students at ASU share their thoughts about place, belonging, identity, and self.

2. Ask the following questions in either small group or larger class discussion formats.

- How are Native students in the videos describing place and belonging at ASU?

- What similarities and differences did you notice in how the students in the videos described place and belonging, and how students in your class identified place and belonging?

- What does belonging (sense of belonging) mean? And how does belonging connect to identity? To place?

- How can we learn about, and learn from, Native people?

- How does learning about, and learning from, Native people help us expand our own understandings and connections to the places we live?

Exploring the Resource: “Land-Grab Universities” from High Country News

- Review the project page, Investigating Land Grants to Universities and review the following terms with students:

- Land Grant University

- Morrill Act of 1862

- Land cessions

- Treaty

- Endowment

- Wealth transfer

- Engage students in a discussion about the article, "Land-Grab Universities” by Tristan Ahtone and Robert Lee for High Country News, using the following questions:

- Who signed the Morrill Act of 1862, and what did the Morrill Act say?

- What are land-grant universities?

- What were the different ways that the U.S. government acquired the land that was then given to land-grant universities as a result of the Morrill Act?

- How did land grant universities earn money from land grants they received as a result of the Morrill Act? How are universities continuing to earn money from land they acquired as a result of the Morrill act? Provide examples from the article.

- What has been the lasting impact of the Morrill Act on Native communities?

- How have universities and other public institutions addressed this impact?

- In what ways has your community been impacted by the Morrill Act? Students can use the resource landgrabu.org/universities to analyze how universities in their communities may have benefitted from the Morrill Act.

*Note: If students have not already read the article, students can read the article in class on their own or they can start by reading the first section together and then working in small groups to review the rest of the article. If they work in groups to review the article, each group should assign one of the remaining sections of the article to one group member. After all students in a group have read their sections, students should summarize the section they read for the other members of the group.

Discussion:

- If students haven’t already, ask them to review one or more of the following articles:

- Nash, M. A. (2019). Entangled Pasts: Land-grant colleges and American Indian dispossession. History of Educational Quarterly, 59(4), 437-467.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., & Tachine, A. R. (2021). Myths, erasure and violence: The immoral triad of the Morrill Act, Native American and Indigenous Studies, 8(1), 149-144.

- Brayboy, B. M. J. & Lomawaima, T. K. (2018). Why don’t more Indians do better in school? The battle between U.S. schooling and American Indian/Alaska Native education, Daedalus, 147(2), 82-94.

- Engage students in a discussion about the readings in the lesson using the following questions:

- Based upon the readings, how is land and property conceptualized in higher education?

- How does land and property influence place and belonging?

- What does it mean for universities to occupy and benefit from Native homelands?

- What does it mean to live and work on Indigenous lands?

- What recommendations do you have for colleges and universities that benefit from the Morrill Act and Land Grab?

Extension Activity:

1. Revisit the article "Land Grab Universities" and website www.landgrabu.org to explore connections between Tribal Nations, land, and colleges. In groups, select one university or Tribal Nation from the landgrabu.org website to further explore. Then, use the instructions below present the following information based upon university OR Tribal Nation you select for your research:

Option A: If you select a university to explore, please present the following:

- Overview of land cessions: Tribes impacted, total land cessions/Tribe, total acres of land/Tribe, U.S. dollars paid/Tribe, money raised amount (adjusting for inflation)/Tribe.

- Provide enrollment and graduation numbers of Native students at the institution (show trend overtime), support services available for Native students, and any other examples of relationship building between the university and Tribes.

- Select one Tribe that is connected to the university and provide brief historical information of the Tribe as well as information about the contemporary (sociopolitical) realities (suggestions are provided below) that the Tribe is facing.

- Hint: Research to see if they have a Tribal website, Tribal newspaper, and or radio.

Option B: If you select a Tribe to explore, please provide the following:

- Overview of land cessions: Treaty information, total acres of land parcels, & U.S. dollars paid/acres.

- Universities benefiting from Tribal land grants: List of universities/states, total acres/university, U.S. dollars paid/university (adjusted for inflation), total money raised amount (adjusted for inflation) for (how many) universities.

- Research about the Tribe that includes brief history, current total population, current Tribal location, & sociopolitical realities facing the Tribe (suggestions are provided below).

- Select one university that benefits from the Tribe you selected. Provide enrollment and graduation numbers of Native students at the institution (show trend overtime), support services available for Native students, and any other examples of relationship-building between the university and Tribes.

2. Write (xx words/pages up to the educator) OR create a 8-minute video or podcast audio clip describing and presenting what you learned from Native peoples, sources, or knowledge bases as part of your research.

The writing/video/podcast should also explore the questions below.

- What does it mean for universities to occupy and benefit from Native homelands?

- What does it mean to live and work on Indigenous lands?

- How are Tribal Nations asserting educational sovereignty in the current context?

- What recommendations do you have for colleges and universities that benefit from the Morrill Act and Land Grab?

The following are examples of sociopolitical realities to consider exploring: Choose from the following list of topics or interest areas:

- Achievement in the arts, visual, film, literature etc.

- Arid lands agriculture

- Boarding schools to tribal colleges

- College attainment

- Grassroots community development

- Resource management: forestry

- State impacts of Indian gaming

- Water rights

- What is sovereignty?

This lesson is aligned with the following Common Core standards:

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.