Last week, four grieving American families won a bittersweet victory in Washington. Setting aside their sorrow and deep sense of betrayal, the parents of four American hostages killed in Syria met face-to-face with the president they said had failed them.

Accompanied by two dozen relatives of current and former hostages, the parents of James Foley, Steven Sotloff, Peter Kassig, and Kayla Mueller had a private 45-minute meeting with Barack Obama. The gathering was the culmination of a six-month U.S. government review of how Washington has responded to kidnapping cases since 2001.

More than 80 Americans have been kidnapped by terrorist groups or pirates since 9/11, the investigation found. More than half returned home safely. And more than 30 U.S. citizens are being held hostage overseas today, including Americans abducted by criminal or drug gangs.

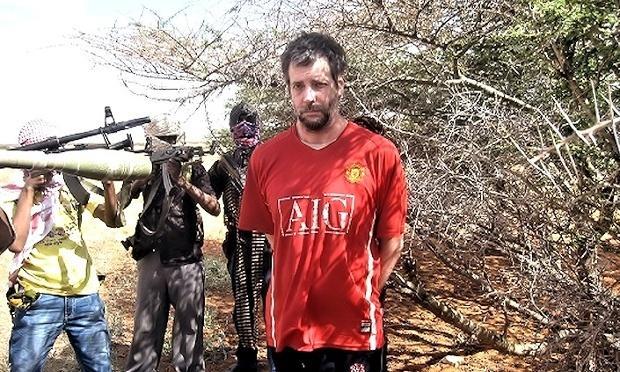

Washington's efforts to free hostages and counter terrorism have also inadvertently killed American captives. Among the attendees were the mother and brother of Luke Somers, a 33-year-old freelance photographer killed by his captors in Yemen last December during a failed U.S. military rescue attempt. A month later, a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan accidentally killed Warren Weinstein, a 73-year-old American aid worker being held hostage there. Weinstein, who was Jewish, somehow survived three and a half years as a captive of al-Qaeda—only to die at the hands of his own countrymen.

Six years ago, I was kidnapped by the Taliban and held captive for seven months in the same part of Pakistan. With the help of the Afghan journalist abducted with me, I was able to escape from captivity. My wife also attended Wednesday's meeting.

Throughout the meeting, a famously detached president was warm, welcoming, and candid. He took the time to shake hands with each participant—both at the beginning and end of the gathering. After addressing the entire group for 10 minutes, he listened patiently as the families asked pointed and poignant questions. Obama openly admitted the government's failings, he said he understood the families' frustration. He agreed that the families deserved better. The president said he, too, would try to move heaven and earth if one of his daughters were taken captive.

Minutes after that private meeting, Obama held a press conference at which he unveiled Presidential Policy Directive 29, a reorganization of how the U.S. government responds when Americans are taken captive overseas. Obama publicly declared what FBI officials have privately said for years: He promised that American families who pay ransoms would not be prosecuted for providing material support to terrorist groups. He said government negotiators would, for the first time, engage in direct talks with kidnappers. And he pledged that U.S. intelligence officials would try to maximize—instead of curtail—the amount of intelligence information shared with families.

In a series of organizational changes, Obama established an official Hostage Response Group that will meet at the National Security Council to review the status of hostage cases. The State Department will have a new senior official, a special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, to push for aid from local governments. And the FBI will house an interagency Hostage Recovery Fusion Cell of experts from across the government who will try to resolve cases.

But Obama said there would be no change in the longstanding U.S. policy of not paying ransoms. He made no mention of the largest challenge the families face beyond the kidnappers themselves: European government policies that allow ransom payments.

For decades, France, Spain, Italy, and other European governments have paid direct and indirect ransoms to free their citizens. While four American and three British citizens held hostage by the Islamic State were killed, 14 Europeans held prisoner by that group were released after ransom payments. U.S. officials estimate that between 2008 and 2014, radical Islamist groups received $200 million in ransoms.

As a result, American families face a staggering challenge: raising the estimated $1 million to $2 million in ransom money that has become the norm demanded by extremist kidnappers. Until there is a coordinated approach with Europe, Obama's reforms will help the families of hostages, but not necessarily help free captives themselves.For decades, France, Spain, Italy, and other European governments have paid direct and indirect ransoms to free their citizens. While four American and three British citizens held hostage by the Islamic State were killed, 14 Europeans held prisoner by that group were released after ransom payments. U.S. officials estimate that between 2008 and 2014, radical Islamist groups received $200 million in ransoms.

To their credit, the families hailed the changes. "We have faith that the changes announced today will lead to increased success in bringing our citizens home," the Mueller, Kassig, and Sotloff families said in a joint statement. The Foleys, whose son James was killed brutally, praised the review for "shining a spotlight on the silent crisis of American citizens kidnapped abroad."

The families' magnanimity is remarkable. In a scathing New Yorker article published the day Obama announced his reforms, Lawrence Wright details the families' desperate efforts to save their children. With the help of the owner of The Atlantic, David Bradley, the families created a private network of dozens of people to try to locate the hostages and somehow free them.

Instead of aiding those efforts, the government complicated them. Two senior officials in the White House and State Department repeatedly warned the families they could be prosecuted if they paid a ransom. FBI officials, however, assured them they would not be. Other FBI agents, meanwhile, told the families to stop trying to contact intermediaries in the region. All the while, officials across the government shared little information about what the U.S. government was doing to free the hostages.

After Obama's announcement, critics said the changes were too little too late. They also said Obama should have made it clearer to kidnappers that they would face lethal American retribution. All critics called for greater support for the families, while also demanding that no concessions be made to the hostage-takers. The two goals are contradictory. If a hostage cannot be rescued by force, a ransom is the means to free him or her. In kidnappings, you cannot have it both ways.

More important, the criticisms fail to take into account the mentality of jihadist kidnappers. Based on my experiences and conversations with a half dozen other captives held by jihadists, militants who kidnap foreigners do not conduct cost-benefit analyses before abducting them. In the perverse world of jihadists, they long for death and gain vast, non-monetary benefits from kidnapping a foreigner. Taking an American captive immediately boosts the standing of commanders in jihadist circles. The payment of ransoms by European countries, meanwhile, creates an incentive for jihadists to abduct any foreigner they come across. Europeans can be sources of cash; Americans sources of fame.

With instability spreading across the Middle East, the availability of one of the kidnappers' most important tools—lawless areas where they can hide captives—is also growing. One reason for optimism in an otherwise dismal landscape of burgeoning global kidnapping involves recent successes in Colombia and the Philippines. In both countries, long-term U.S.-led efforts to properly fund and train local security forces have shrunk the safe havens where hostages can be held.

The changes announced last week in Washington are also a major step forward. The credit for the change goes to the families of the four captives who perished in Syria. Ordinary Americans—three nurses, a doctor, a body-shop owner, a vice president of sales, and a high-school biology teacher—rose above their pain.

Journeying from Arizona, Indiana, Florida, and New Hampshire, they held Washington accountable. They deserve Americans' admiration, not their pity.