Pulitzer Center grantee Maria Parazo Rose and her colleagues at Grist set out to question a practice “so foundational” in the United States that it is carved into the ground. Parazo Rose, who traveled from Pittsburgh to speak at the University of Missouri, showed a photo of patchwork plains and farmland that she took when her plane descended into the state.

The United States parceled these state trust lands after ratifying statehood. They seized many of them from Indigenous nations. In all, 30 states were allocated trust lands.

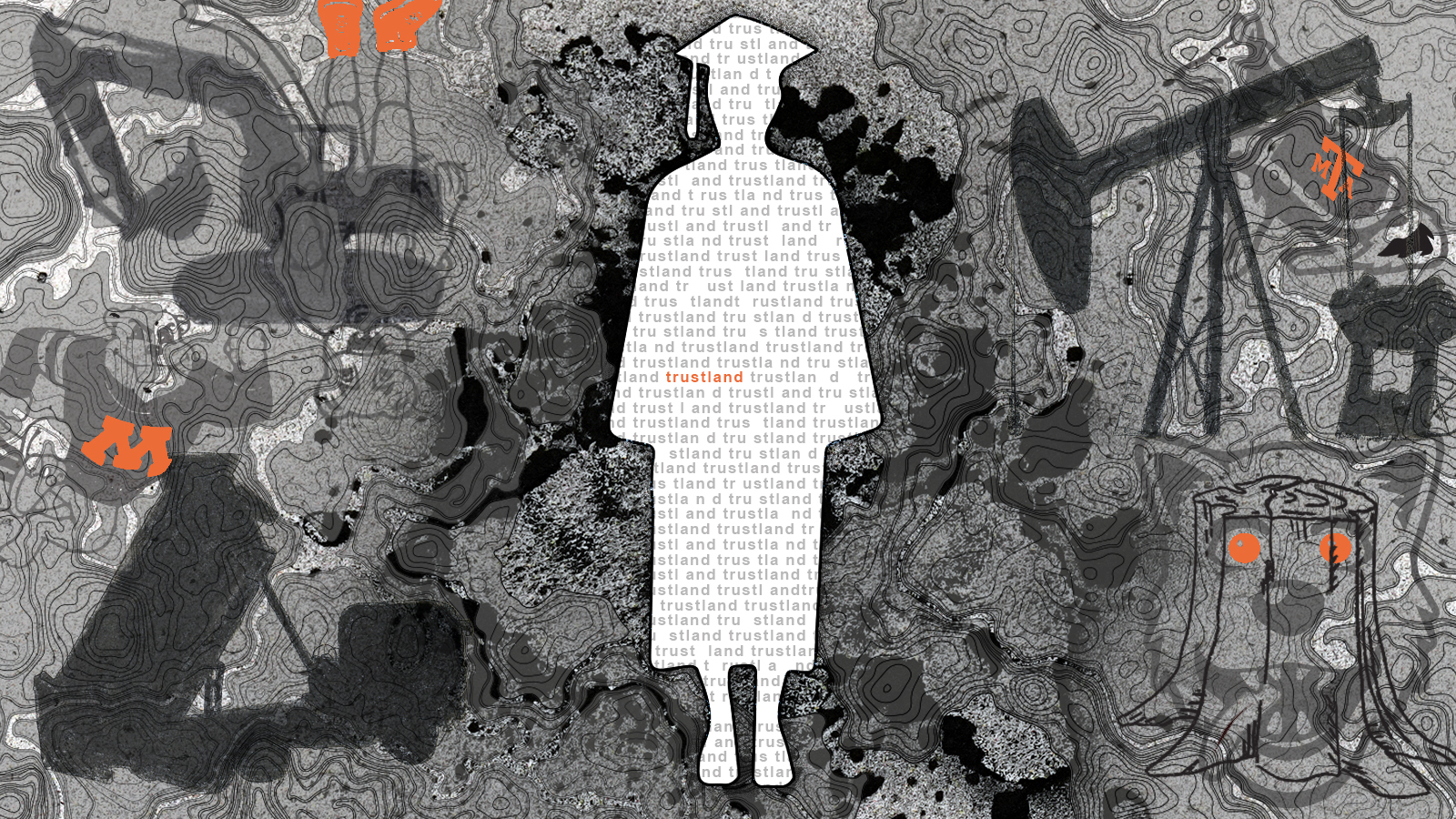

The trust lands were intended for building government institutions or to be sold for profitable development. But few states sold the lands to private interests; instead, they gave them to state schools like University of Arizona, the University of California System, the University of Missouri, among many others. All of these schools were supported by the Morrill Act, the subject of an earlier investigation supported by the Pulitzer Center, Land-Grab Universities. Parazo Rose and her colleagues showed that many of these universities continue to profit from state trust lands by leasing them for extractive activities like oil drilling and mining.

Parazo Rose and her colleagues contacted state administrators who were not aware universities profited from leasing state trust lands. They even documented state trust land on Indigenous reservations. A settler colonial dead hand continues to pass money from Indigenous communities to wealthy state universities like Arizona State long after theft by violence-backed treaties and laws.

Indigenous people take on disproportionate student debt to pay for higher education. In Misplaced Trust, Grist profiles Alina Sierra, a University of Arizona Native Scholars Grant first-year student who had to take out a loan to cover expenses like books and food. Nearly 40% of Indigenous students accrued more than $10,000 in college debt, according to a 2022 national study. [After Grist published Misplaced Trust, the university reviewed Sierra’s circumstances and forgave her debt.]

These practices, said Parazo Rose, are connected and “hidden in plain sight due to time, history, and American mythology.”

It amounts, she said, to a “real-time erasure of Native peoples.” Parazo Rose and her colleagues needed to “be able to show it, map it out, collect the receipts—we have better information to ask harder questions.”

Collecting and cleaning data for their interactive maps, which Grist open-sourced, was a significant challenge.

“It’s very easy to be territorial,” said Parazo Rose, “but I liked that we shared our data before we published. [I] trust[ed] that the impact we were aiming for requires more than one person.”

Indeed, Land-Grab Universities inspired her work on Misplaced Trust. She hoped to do the same for students at the Missouri School of journalism: This data “can be redesigned and applied to questions you might have,” she told students.

Later in the evening, Melissa Horner—a doctoral candidate in sociology, citizen of the Manitoba Métis Federation, first-generation unenrolled descendant of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and Jaquetta Shade-Johnson, assistant professor of English and digital storytelling, and citizen of the Cherokee Nation—discussed solutions-building with Parazo Rose.

A total of 24 people worked on Misplaced Trust. Some additional resources include: