There are two ways to think about diversity, moderator Yochi Dreazen of Vox said in his opening comments for the “Diversifying the Story” panel discussion at the Pulitzer Center Gender Lens Conference on Saturday, June 3, 2017: The first is that there should be more women and people of color in journalism. The second is that there should be more stories about women and people of color.

In the hour that followed, the panelists discussed those and many more aspects of diversity, including class, sexual orientation, and national and cultural identity. They concluded, sometimes with a weariness and frustration born of personal experience, that despite some progress the news business is still dominated by coverage by, for, and about white men.

“Journalism is still very colonial,” said freelance photographer Daniella Zalcman. A persistent lack of diversity in the field, she said, is “embarrassing and toxic” and calls for a reframing of narratives. Zalcman’s recently published book, Signs of Your Identity, and her formation of the Women Photograph database of female freelancers, represent two examples of what she calls a “solutions perspective” to the problem.

Perhaps the most upbeat voice on the panel belonged to Susan Goldberg of National Geographic Magazine. Goldberg observed that when she arrived at National Geographic in 2014, three quarters of the magazine’s stories were written by men, the vast majority of them white. Last year, that number had dropped to 57 percent.

“We are going out and finding new people,” said Goldberg, who added that about a third of the reporters writing for National Geographic now had been on the job just a few years, and of those, 60 percent are women.

That shift has already had a noticeable impact on the stories in the magazine, she said, pointing to the January 2017 “Gender Revolution” issue as an instance of newly diverse narratives emerging at National Geographic. Goldberg is proud of that issue, but said that some 8,000 subscribers had cancelled their subscriptions after seeing a transgender child on the cover. “Many of them had not even opened the plastic wrap,” she said.

Barriers to entry in journalism are a major cause of the ongoing lack of diversity in the profession. Nikole Hannah-Jones, a New York Times investigative reporter, said that editors tend to hire in their image, closing women and journalists of color out of fields like investigative and science journalism and pigeonholing them into race or gender reporting.

“I’m not a good race writer because I’m black,” said Hannah-Jones. “I’m a good race writer because I’ve studied it. You’d never cover climate change without studying climate.”

The difficulty of making ends meet in journalism as a career, never far from the surface in any discussion, bubbled up frequently as a particular problem for journalists of color, many of whom come from working class backgrounds that oblige them to be able to support themselves independently.

“When I go to private schools kids ask about kidnapping and the ethics of journalism,” said Zalcman. “When I go to public schools they want to know how much I make and how much it costs to be a journalist.”

Fareed Mostoufi, senior education manager at the Pulitzer Center and a frequent collaborator with Zalcman in schools, agreed that in under-served public schools in DC, “kids want to know how you survive” as a journalist.

Hannah-Jones said that for years, “I was a newspaper reporter who sold mattresses on the side.”

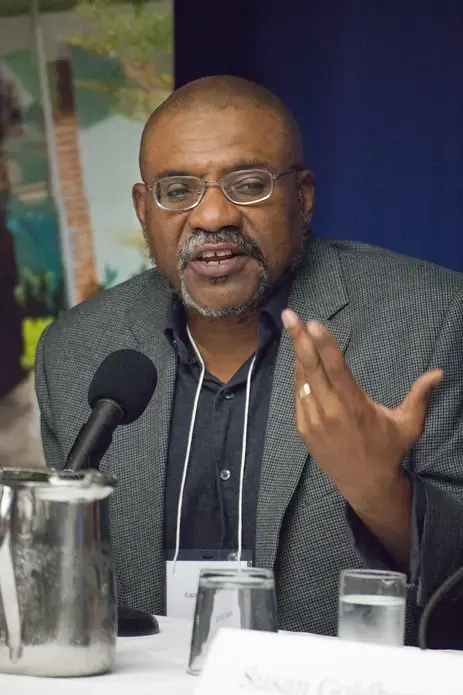

Kwame Dawes, whose Pulitzer Center grant led to an Emmy Award for new approaches to news, put the socio-economic argument into perspective: “I kind of find it funny because I work with poets.”

For more than a century, many Western governments operated a network of Indian Residential Schools...

Project

Kuchus in Uganda

As Uganda struggles with anti-homosexuality legislation, the growing LGBT-rights movement continues...