The New York Times Magazine's monthly photography column highlighted the work of Pulitzer Center grantee Daniella Zalcman last week in an essay about photographing indigenous cultures from both an inside and outside perspective. The column, written by photographer Teju Cole and entitled "Getting Others Right," compared Zalcman's work on her project "Signs of Your Identity" to other portraiture, both historical and current, of Native Americans and indigenous people.

Cole examines the pitfalls of successful, but in hindsight problematic projects such as Edward S. Curtis' "The North American Indian," an exercise in staged, stagnant portraits that offered Native Americans only in their idealized "characters." Cole questions if outsiders truly ever get other cultures right and if they should try at all. Cole offers the work of modern native photographers such as Brian Adams, Josué Rivas, and Camille Seaman, as well as Horace Poolaw who photographed in the same period as Curtis, as examples for why it works so well when people tell their own stories. A view that Zalcman shares, most recently at Pulitzer Center's Gender Lens conference in panels on diversity and female photographers.

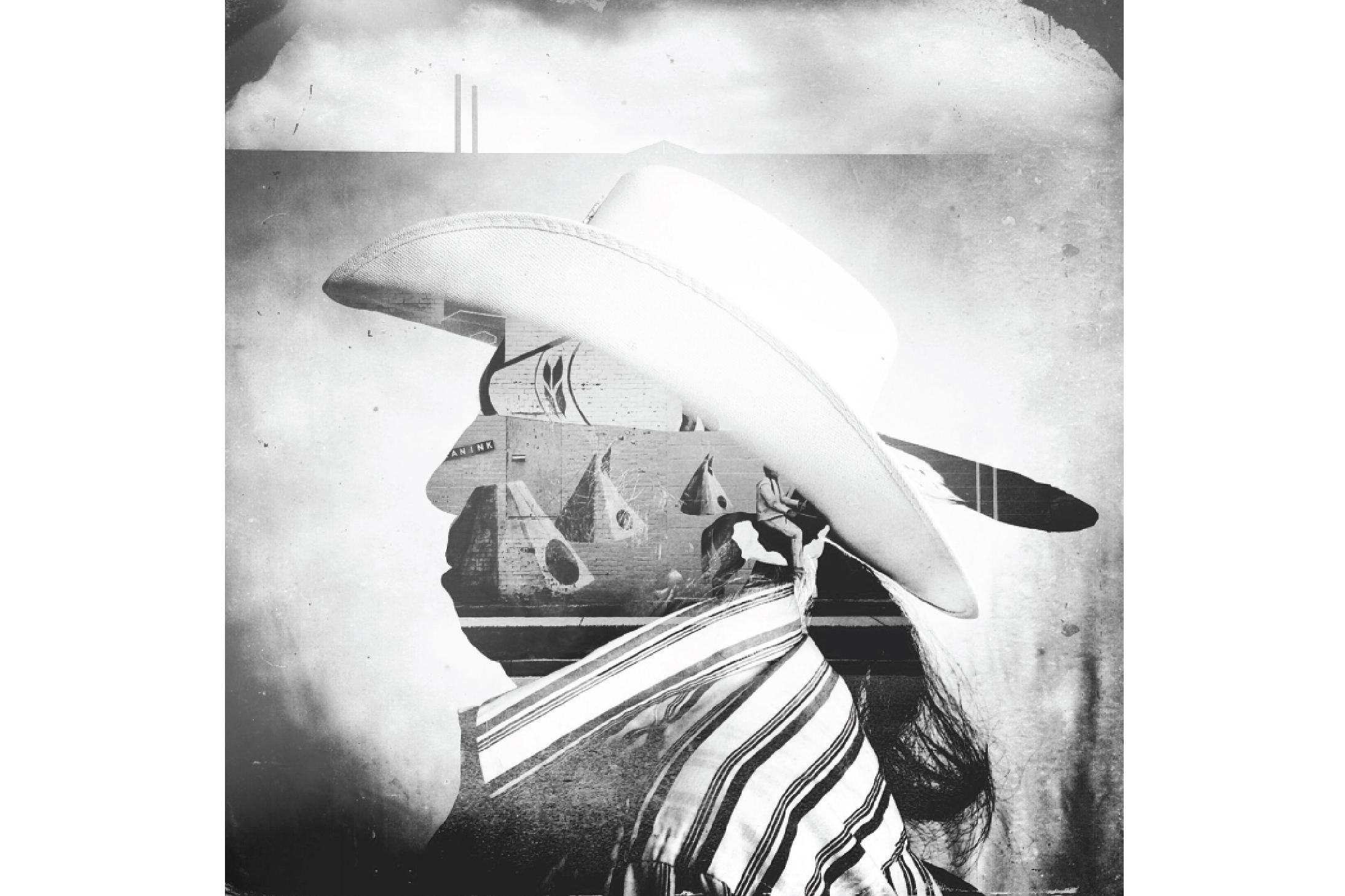

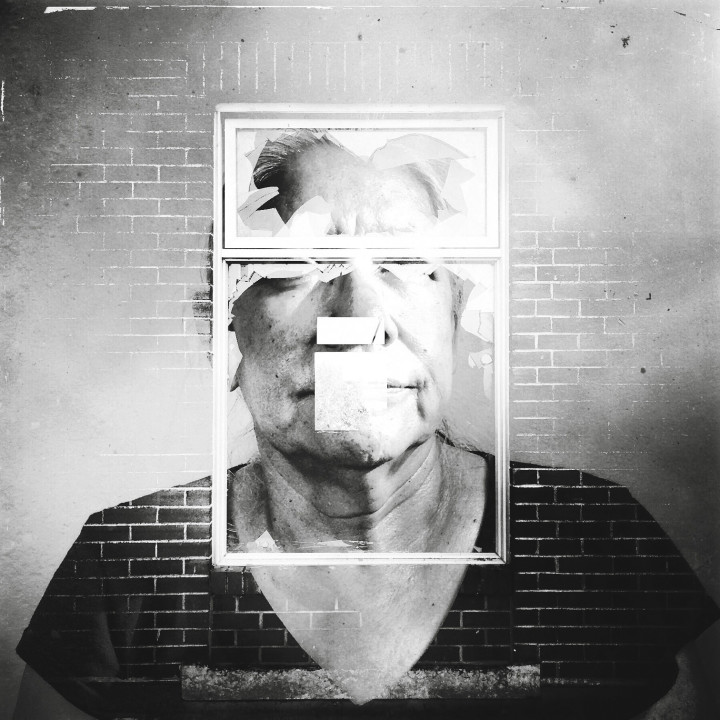

Cole lands on Zalcman's work as an effort in proving both effective and non-effective ways to photograph indigenous cultures. Zalcman's first batch of images depicted indigenous substance abuse and high HIV rates was an exercise in the latter, one that "risked further stigmatizing the community." When she came back to try again, Zalcman decided to focus on survivors of Canada's Indian Residential Schools, using double exposure to "focus on individual experience" and their memories.

"Looking at the doubled images, you imagine that the mind of the person pictured is literally occupied by space on which it is overlaid: the decrepit school buildings, the grass where a demolished school once stood. But you also sense that this could be you, that these images are not a report on tribal peculiarities but on the workings of human memory. Uncertain about her right to shape the story, Zalcman lets the subjects speak for themselves. This hesitancy is productive: She manages to accomplish quietly forceful reportage from material that could easily have been sensationalized."

Cole emphasizes that photographers "prioritize justice over freedom" when they are telling stories that aren't theirs. He says "it is not about taking something that belongs to someone else and making it serve you but rather about recognizing that history is brutal and unfinished and finding some way, within that recognition, to serve the dispossessed."