"Asking a really broad question is okay to start an interview," photojournalist Dominic Bracco told the group of Chicago teenagers in a second-story classroom at Power House High School on Chicago's West Side. "What would you ask a police officer?"

"How does it make them feel that everyone thinks they're the bad guys?" one student piped up.

"How do they feel about being portrayed in the media, people portraying them all the time?" another added.

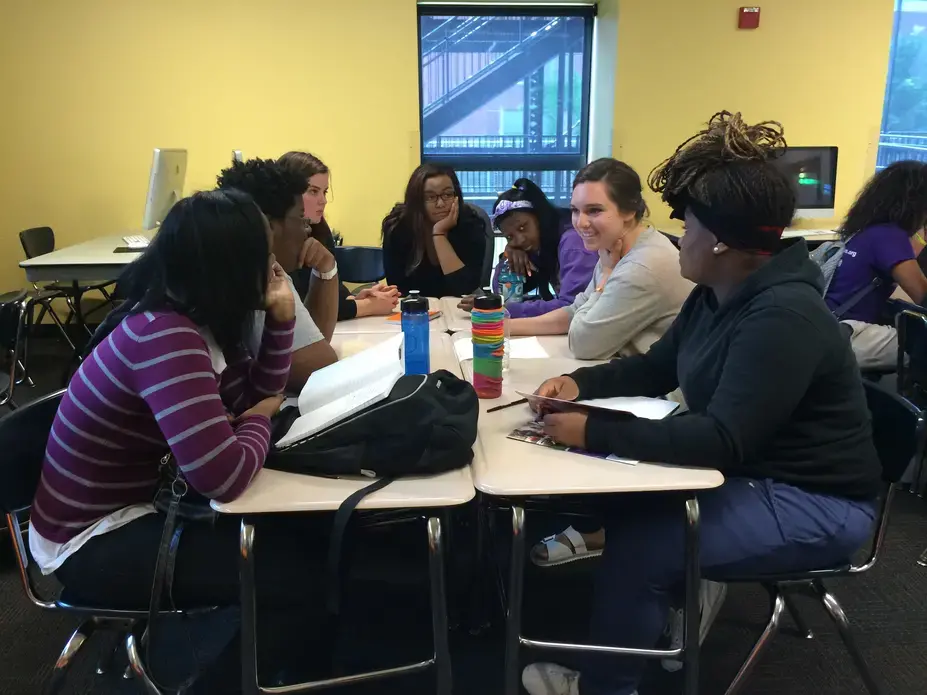

It was late June 2015, and the 16 students had been accepted into a collaborative summer program run by Chicago-based Free Spirit Media and the Pulitzer Center. They would spend the next six weeks researching, planning, shooting and editing short documentary films on local issues that mattered to them, mentored in their day-to-day work by Free Spirit staff and remotely by four Pulitzer Center visual journalists: Evey Wilson, Jon Lowenstein, Meghan Dhaliwal and Dominic Bracco.

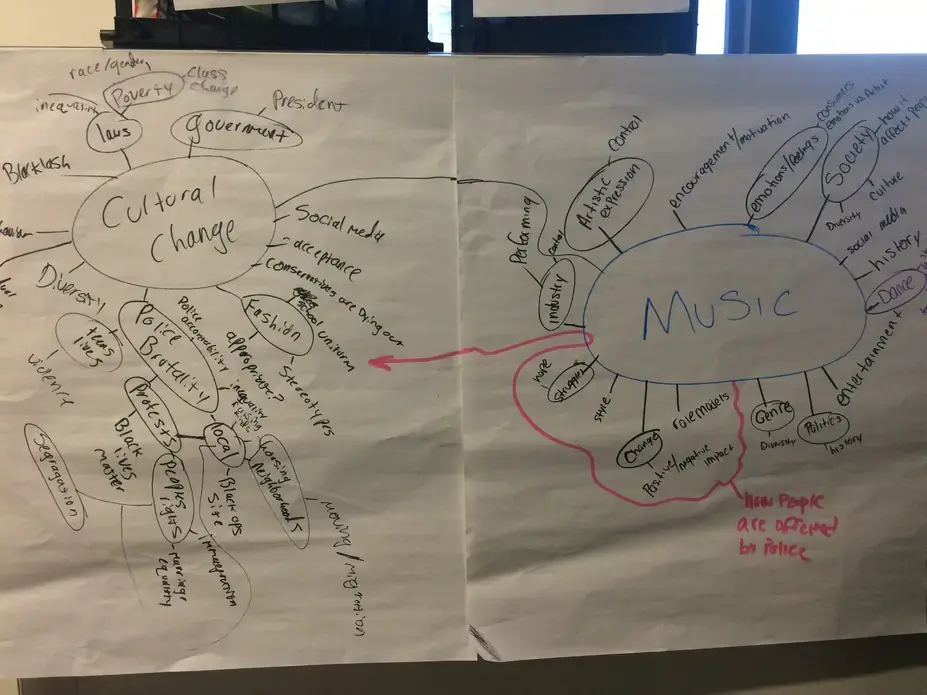

Before a summer of Skype chats and e-mails, though, the journalists met with their groups in person for two intensive workshop days, where they brainstormed topics the students wanted to explore in their documentaries. They also talked about the journalists' own work – Bracco's photography in Mexico and along the border; Dhaliwal's photos of "packing up" the war in Afghanistan; Lowenstein's images and video from protests in Ferguson, Missouri last summer; and Wilson's short film on the lives and futures of previously incarcerated persons.

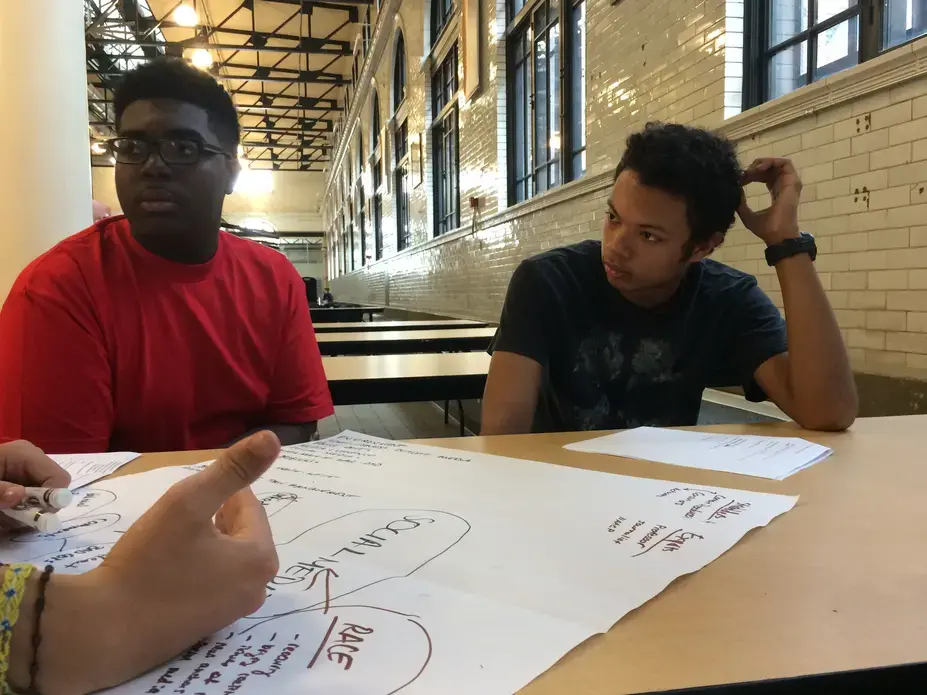

In their film, Bracco's group decided to focus on the ways the United States' conversation about race has changed in the social media age. Lowenstein's team, interested in the issues behind the visuals he'd shared, made their film about Chicago hip-hop artists who address police brutality and inequality in their work. Dhaliwal's students focused on one young man with depression, and Wilson's team explored LGBTQ and interracial relationships.

A key part of the Pulitzer Center's role is to help the students realize that the topics they're exploring in Chicago – race, police violence, mental health, discrimination against nontraditional relationships – are global. After some research by the groups, their films also addressed what the issue looks like somewhere else in the world.

During those first two days and in their subsequent discussions, the journalists and their mentees discussed the basic tenets of journalism and how to work through a reporting project on a difficult, contentious issue.

"When you're interviewing somebody, you don't go up to them and go, 'So why are you a racist?'" Bracco said. "But that doesn't mean you don't ask them hard questions, right? Journalism teaches you critical thinking skills, but it also teaches you empathy. We can think they're wrong and they can be wrong, but we can still listen to them."

The groups approached their subjects with sensitivity, having done their research and having been well coached.

"I'm so proud of you guys for being open enough to make [your subject] feel comfortable," Dhaliwal wrote in an email to her group at the end of July. "That can be really tricky, so you guys seriously did a great job."

On the evening of August 10, all four journalists gathered back in the same classroom, along with over 50 other people, including their groups, Free Spirit staff, and families and friends, for the first public screenings of the films. The filmmakers told the crowd what they'd learned in the program.

"I improved my communication skills," said Kahla, "and I understand how media works behind the scenes."

Yahyness said she learned about "working with others and getting to the next step in film, and I also learned a lot about LGBTQ and how society views them."

"The journalists provided us with a lot of love and support and connections," said Taya.

The program was also supported by After School Matters and the Foundation for Homan Square and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.

Project

Honduras: "Aqui Vivimos"

"Honduras: Aqui Vivimos" ("Honduras: We Live Here") explores the social conditions—abject poverty...