Saharan dust can be a good thing. But warming seas and rising temperatures may shift these sands in the sky.

1. Sun

Deep in the Sahara Desert, the sun heats the sand, and the air above it rises. The rising air carries dust — orange dust from Mauritania and Mali, white dust from an ancient lake in Chad. Clouds of dust that soon flow into a jet stream moving westward across Africa, an ochre haze moving toward a place where our worst hurricanes are born.

It’s here in this hurricane nursery off the western African coast where 80 percent of the Atlantic’s most destructive tropical cyclones formed, including Hugo, which dealt Charleston a devastating blow in 1989.

Here, near Senegal and Mauritania, dust from the Sahara also merges with the trade winds — the same winds that propelled slave traders across the Atlantic centuries ago, the same winds that steer our tropical storms.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

Embedded now, the dust fans out for thousands of miles. To the Caribbean and Brazil, where it enriches the rain forests with phosphorus and iron. To Texas, Louisiana and the Carolinas, where it makes our sunsets even more spectacular.

On its way, Saharan dust also can snuff out a dangerous storm, like a blanket on a smoldering fire. Last year, giant Saharan dust clouds did exactly that, tamping down Atlantic hurricanes through early September.

This year is different. The Sahara launched less dust. Seas off West Africa grew warm early. Without that dust blanket, two tropical cyclones formed and soon gathered strength. One is named Bret, and behind it is Cindy. They are among the earliest named storms to spin out of West Africa’s hurricane nursery.

So Saharan dust can be a good thing, at least when it comes to hurricanes and sunsets.

But Moussa Gueye knows that these forces — the dust, the warming seas, the rising temperatures — may shift these sands in the sky.

Gueye can see it from his university post in Kaolack, a dusty and hot city in Senegal’s interior. He knows that new research suggests a rapidly warming climate could weaken the wind jets that carry the dust. That could mean less dust moving into the hurricane nursery, less dust to beat down those storms. He has also seen signs of the opposite, that climate change could generate more dust.

This uncertainty is personal for Gueye and scientists in West Africa, who have received less attention for their climate work because of science’s long tilt toward Europe and the United States. But these scientists have seen the towering clouds of dust consume their cities, felt the grit in their food. They’ve found intriguing strains of bacteria hitchhiking on the particles. They’ve lived and breathed their work.

In Gueye’s case, he knows these forces can suddenly change everything, whether it’s dust or waves. He saw this happen when he was 6 years old, on a terrifying night that eventually sent him spinning toward science for answers. Toward math specifically, because sometimes you can apply math to life and identify potential dangers, maybe give you enough warning to move out of harm’s way.

2. Seed

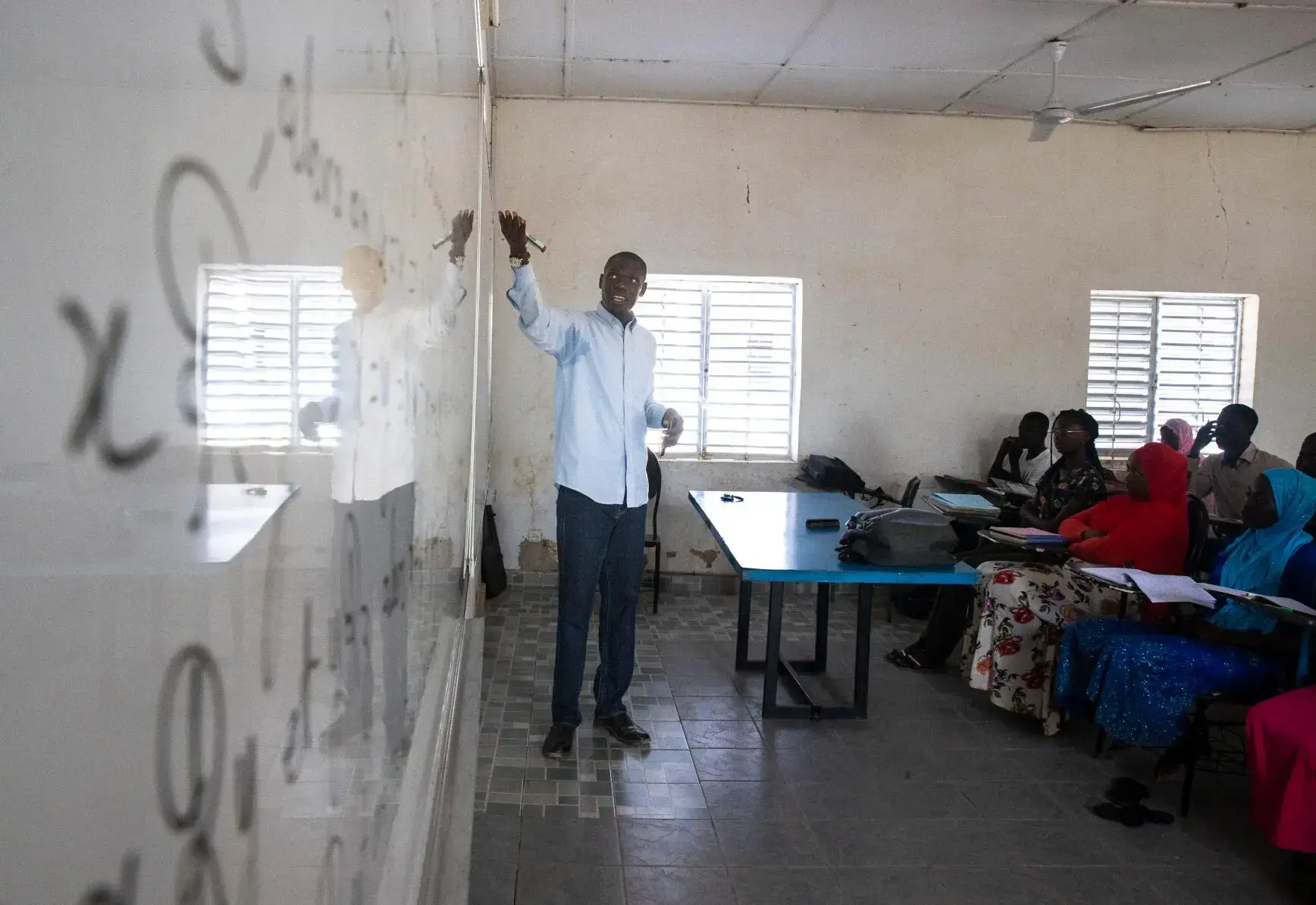

Gueye (pronounced “geh”) is a tall and thin man with a scruff of hair on his chin. He’s a professor of applied mathematics at USSEIN, a university in Kaolack. The city is known for its salt ponds and peanuts. Peanut piles the size of sand dunes rise next to scattered groves of thorny acacia trees. Not far from one peanut processor are the open-door classrooms where Gueye teaches basic and advanced courses. Sweating one hot morning, he tried like all good math teachers to make abstract concepts relevant to his students, which he sometimes does by offering his life as a proof.

He was born about 70 miles west, in the coastal town of Mbour. His father and uncle were fishermen, plying the waves in wooden pirogues, long banana-shaped boats often painted green, yellow or red, the colors of the Senegalese flag. The name Senegal itself comes from sunugal, the Wolof word for “our boat.” In the 1990s, he and his friends had enough space to play soccer, with plenty of beach left for the pirogues that lined the shore. But the waves seemed to grow closer year by year.

Then, one night when he was 6, the Atlantic poured in. Like thieves, the waves ransacked his uncle’s house. Families fled for their lives as the sea stole their belongings. As the water receded, Gueye tried to wrap his mind around what had happened. No evil person was responsible, he thought. It was something more powerful.

That night of high water was the seed that grew into questions about the forces of nature and how they work. But his curiosity about the power of water and wind had already been fertilized by his father. His father had been pushing his older brother to become a fisherman, but not Gueye. He was good in school, especially science. His father knew the world was changing, that fishing wasn’t as promising as it once was. Focus on your schooling, he told Gueye, who would go to Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Senegal’s capital, then seek his doctorate in France, where he would apply equations to a changing climate.

In France, Gueye had a conversation one day with an advisor about a global climate model. Something was missing, he said.

Climate models are the cathedrals of earth science. They break the planet’s atmosphere and oceans into cubes packed with data on temperature, ice and winds. Computer programs then analyze what happens in those cubes to identify patterns. The programs have become so complex they require banks of computers in warehouses as big as football fields. With increasing accuracy, these models predict the likeliest paths of our climate, just as smaller hurricane models forecast paths of tropical storms. Scientists run the climate models backward in time to see if their projections of the past match what really happened. Then they run them forward to see what might be.

But these models are only as good as the real-world measurements in those cubes. The French had one of the leading global climate models. But there in France, Gueye realized that the model didn’t properly account for one of the most important migrations in the world: the Sahara and its dust.

This was surprising, Gueye remembers thinking. Even as a young child, he’d seen how dust clouds made it harder on everyone to breathe. And the Sahara was such an enormous presence in itself, a desert as large as China or the 48 continental United States. But he also knew that this massive region had few long-term weather sensors, which made the Sahara a desert of data.

So, for five years, he crafted a module to plug into the French climate model, gathering data and coding programs to simulate the migration of Saharan dust.

“A lot of work, yes,” he said with a laugh during a recent break in his teaching schedule. “But it also was an opportunity.”

The grand movement of the Sahara’s dust — how could it not be part of the larger climate equation?

3. Dust

In June 2020, a plume of dust flowed off Western Africa and floated 5,000 miles into the Gulf of Mexico. It was a layer of dust the size of the United States and 2 miles thick, and it was among the largest dust clouds NASA had seen in 50 years. It gave the daytime sky in Texas a sickly white glare and the sunsets a burnt orange hue. Its tiny particles triggered allergies in Louisiana. It made headlines as it moved as far north as Illinois. Meteorologists began calling it Godzilla.

Every year on average, the Sahara launches 182 million tons of dust into the atmosphere. Some of the largest dust sources are in Mauritania and Mali, where particles have an orange tint, and the Bodélé Depression in Chad, which has a whitish tinge. In Mauritania, camels lumber by sand dunes so hot you can feel heat rise through the soles of your shoes. And you can easily see the Bodélé Depression on satellite images of Chad: a white eye-shaped indentation the size of South Carolina.

Depending on the winds, African dust may drift north to Europe. During winter, dust sometimes coats ski slopes in France and Spain with a terra cotta-colored film that makes them look like sand dunes. Dust from Chad has been found as far north as Greenland. When dust and rain mix, you end up with a rainstorm of muck. A year ago, a dust cloud from the Sahara passed over Paris, turning the sky the color of pumpkin. Then it fell in the United Kingdom; forecasters called it a “blood rain.”

But much of Africa’s dust flows west, toward the trade winds — dust that if packed into semitruck trailers would fill 700,000 of them. This sky-borne convoy then crosses the Atlantic.

When dust arrives in the Caribbean, emergency room visits increase and asthma complaints spike. Dust is rich in iron and phosphorus, so when it lands in water and forests, it fertilizes phytoplankton, ocean algae that produce half of the oxygen we breathe. Dust also carries harmful microbes. Away from the Sahara, researchers in China found spores from Candida fungi on dust from farmlands, dust that caused heart damage in children. In Senegal, researchers found neurotoxins on dust particles from the Sahara, the same toxins you find in molds that trigger allergies.

Despite the impacts of Saharan dust, scientists didn’t fully understand the desert’s astounding reach until the 1960s, though there had been hints. In 1832 and battling seasickness, Charles Darwin on the HMS Beagle landed in the Cape Verde Islands west of Senegal. He noticed the haze of desert dust, merely calling the high volume “interesting.” In 1956, a German meteorologist found reddish-beige dust in Florida and speculated that it came from western Africa. Then, in the late 1960s, scientists finally connected the dots.

At the University of Miami, Joseph Prospero was studying the effects of seawater bubbles and what happens when they burst. By chance, in 1966, he met a group of British researchers who had been searching in Barbados for evidence of cosmic dust. They had set up filters on the Caribbean island, capturing air from the trade winds. Instead of particles from space, they found their filters caked with red dust. Prospero took over the Barbados filtering project, documenting for the first time the seasonal pulse of Saharan dust across the Atlantic.

Next, Prospero and Toby Carlson, then with a federal National Hurricane Research Laboratory in Miami, pinpointed a river of dust over the Atlantic they dubbed the “Saharan Air Layer.” The layer typically begins 5,000 feet above the ocean and rises another 10,000 to 15,000 feet. For these and other discoveries, Prospero is called the “Father of Dust.”

Prospero and his colleagues opened a door into a new field, one that captured the imagination of another scientist, Gregory Jenkins.

Jenkins also felt the Sahara’s pull, wondering how the Saharan Air Layer affected hurricanes that strike the United States.

West Africa would be his most important teacher.

4. Balance

Like Moussa Gueye in Senegal, Gregory Jenkins also grew up wondering about the forces of nature. The clouds, snow, stars — questions popped into his head as soon as he walked out the door.

His family lived in a row house in Black Bottom, a close-knit, low-income neighborhood in west Philadelphia. His father, Kirby Jenkins, was born in Walterboro, an hour west of Charleston, and later moved to Philadelphia. His father fought in World War II’s Battle of the Bulge, and later worked in the Philadelphia Shipyard. But he died of a brain hemorrhage when Gregory was a child. Jenkins’ mother, a beautician, died when he was a teenager. The deaths left him off balance for a time as a young man, balance he’d regain as his science career spun forward.

Balance, that was what he’d eventually look for in the rotating planet’s winds and seas. He could see the rebalancing in how polar air moved south and warmer air moved north, how ocean currents moved water around the planet like a radiator, how dry air from the Sahara met moist air from the tropics, how a rapidly warming climate upset this balance, especially in Africa.

In the early 1990s, Jenkins went to Niger and Senegal after he finished his doctoral degree at the University of Michigan, and his curiosity gained even more momentum.

Countries in and near the Sahara had suffered through a catastrophic drought that began in 1968 and continued through the 1980s. It was the worst drought to hit the planet in the 20th century, one eventually linked in part to air pollution in Europe and North America and rapidly warming water in the Indian Ocean. The Sahara launched higher-than-normal levels of dust during these two decades, as studies from Prospero’s filters in Barbados would later show. The drought and high dust levels also coincided with a two-decade lull in hurricane activity.

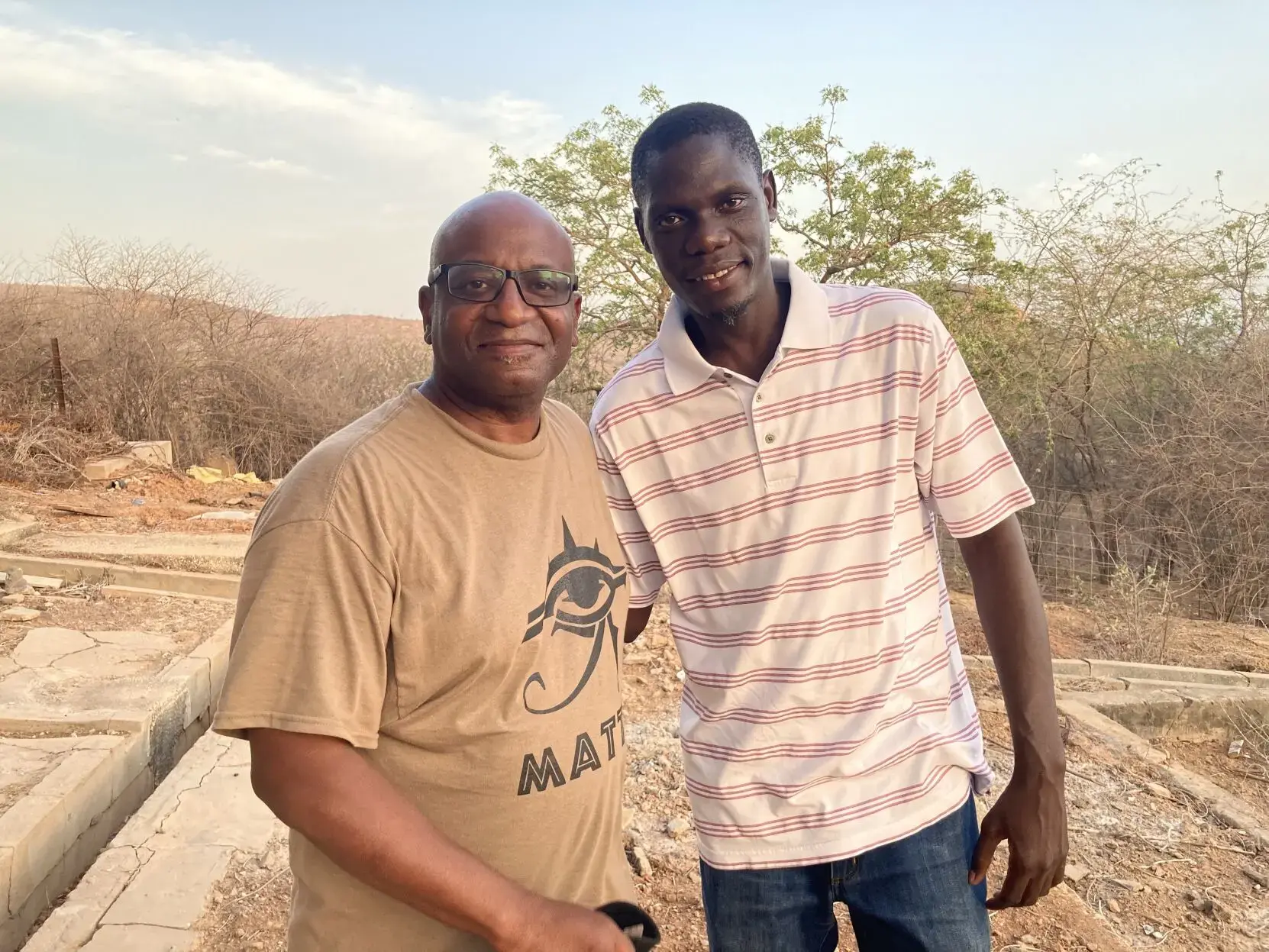

In West Africa, Jenkins, now a professor at Penn State, saw the orange dust, the poverty balanced by social ties, and realized he’d found the place he’d study for the rest of his life.

5. Teacher

Senegal has about 17 million people and is the shape of a lion’s profile facing west. Dakar, its largest city, sits on the lion’s nose. From the 1400s to early 1800s, Gorée Island just off Dakar was a major African slave-trading terminal. Slavers quarantined their captives in prison houses, leading them through a “door of no return” onto ships that rode trade winds to Charleston and New Orleans. The Portuguese, Dutch, English and French all ruled the region at times, but the French were the last to relinquish power. Senegal’s independence came in 1960, and its official language remains French, though many also speak Wolof.

Jenkins visited Senegal year after year, lugging weather instruments with him, his affection for West Africa growing, as well as his questions: How did the drought affect rainfall patterns and dust? How did this dust affect hurricanes? He struck up a friendship with Amadou Gaye, a professor and climate researcher at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar. With 90,000 students, it’s the country’s largest university. Gaye had deep knowledge of the region’s atmosphere. With each trip, Jenkins learned more about West Africa’s people and climate.

Much of Senegal is in the Sahel, a semi-arid belt south of the Sahara. The Sahel is a transition zone, with a tropical landscape to the south that grows more arid to the north. The Senegal River marks the country’s northern border with Mauritania, which has an entirely different feel. Cross the Senegal River and the landscape soon changes into the Sahara’s sea of dunes and wandering camels.

One year, Jenkins hired a pirogue to visit Mauritania, the land that launched so much dust.

“You could see it getting drier and drier, and then you saw just massive sand dunes out there,” he said. “I’d never been in a place like that. The orange dunes. It seemed endless. And people lived there. I remember the food all tasted like sand — dinner and breakfast. The dust got into everything.”

Back in Senegal, he and his new friends pondered more questions: What did climate models say about the Sahara? What might happen as the planet gets warmer? But there was a problem.

“Our tools for this region weren’t good,” Jenkins recalled. They had satellite information, but that wasn’t enough. They needed real measurements: temperature, humidity, wind speeds. They needed to set their feet on those dunes and dust sources, capture what was happening in the skies above these poorly measured places.

“The United States is covered with sensors, but there are just a few in West Africa for 350 million people,” Jenkins said. “How can you have this kind of imbalance?”

In the early 2000s, he returned to Senegal for eight months, working with Amadou Gaye on a campaign to collect key climate data across West Africa. Researchers tracked movements of dust; they monitored the monsoons; more data on dust flowed into climate models, improving their precision. Then more West African researchers published studies in international journals, including Moussa Gueye, who finished his work on the French climate model and spent a year with Jenkins at Penn State.

Said Jenkins, “The voices of scientists in West Africa needed to be heard.”

6. Precision

Today, from Dakar to Saint-Louis to Kaolack, Senegalese scientists have a deep understanding of how their dust-laden storms connect with ours.

They know this connection begins with heat, the blistering sun that bakes the Sahara in Mali, Algeria, Chad and Mauritania. As the air rises from that heat, winds from the north rush in to fill that imbalance, said Moussa Gueye in Kaolack.

When the wind has enough velocity, it scoops up the dust. During the dry season, these winds are called harmattans, a West African word derived from the words “to blow” and “tallow,” animal fat used to keep skin from drying out. When the harmattans reach Senegal, they paint the sky a smoky brown for months.

This dry season typically ends in May and June, added Mamadou Drame, a climate scientist in Dakar who also works with Jenkins. Just before the rains come, storms churn through the Sahara, hoisting enormous amounts of dust. These fierce storms are called haboobs, Arabic for “strong winds.”

As haboobs cross Senegal, they create mile-high walls of brown. Visibility can drop to almost zero. Drame remembered a storm during his childhood that peeled off metal roofs in his village.

“It looks like the end of the world is coming at you,” he said.

The haboobs can be scary, but they often precede the season’s first rains. So fear of the storm is balanced by relief that the dry season is over, Gueye and Drame said.

There’s a second factor at work — the jet stream flowing across Africa. Dust in this westward-moving air current eventually meets the rising winds off the Senegalese and Mauritanian coasts.

Like a springboard, the collision of these winds pushes dust even higher. This is where the Saharan Air Layer takes its shape over the Atlantic. Embedded in the trade winds, the layer becomes “a long local road to America,” Drame said.

The Saharan Air Layer typically has half of the moisture of the air below. This warm and dry air makes it more difficult for clouds to punch through, smothering potential storms, said Abdou Lahat Dieng, another Dakar researcher specializing in the genesis of tropical storms.

If the layer is especially thick with dust, it also blocks some of the sun’s energy. Less sun means less heat going into the ocean, less fuel for developing cyclones.

In other words, Dieng said, the coastal zone off western Africa is often where storms are born or die.

Has climate change affected these forces?

Here, the scientists form a chorus. They said they’ve all seen dramatic changes in West Africa’s climate: More punishing deluges, more frequent droughts, more severe dust events. Disruptions that forced farmers to move to new megacities such as Dakar or cram into pirogues headed toward Europe, ripples of social and atmospheric change that spread far beyond the Sahara.

“You can’t understand what’s happening to the world,” said Amadou Gaye in Dakar, “if you don’t understand what’s happening in Africa.”

7. Warnings

It’s clear that we’re seeing more extreme events now, in Africa and across the planet. But NASA researchers recently asked themselves and their computer models: Will there be more or less dust in the future?

They ran simulations, and the results were surprising — less dust from the Sahara. Much less.

The reasons were nuanced and relate to the many factors West African scientists have experienced and studied — the heat sink that is the Sahara, the westward-flowing African jet stream, the storm nursery off the coast of Senegal, the trade winds that carry dust toward the Carolinas. The NASA models predict these trade winds would weaken, and that a weaker African jet would allow bands of thunderstorms in the tropics to migrate north into the Sahara and its edges. This would dampen the dust as the climate tries to rebalance.

Less dust in the air means the ocean will absorb more of the sun’s heat, creating a feedback loop that accelerates the overall warming trend. The models predicted a 30 percent decrease in the amount of dust over the next 20 to 50 years. Less dust means fewer nutrients going into the oceans that fertilize our oxygen-producing phytoplankton.

Less dust to snuff out our hurricanes.

At the same time, Gregory Jenkins and Moussa Gueye see evidence in the models that point to a different horizon — that a warming planet will make the Sahara even hotter, generating more dust. Their new unpublished research suggests there will be bigger blasts of Saharan dust over the next 30 years.

“I personally don’t think the dust will decrease,” Jenkins said. “But the truth is, we don’t know for sure. That’s why we need more data.”

The stakes are as high as the dust clouds that smother our storms and beautify our sunsets. If NASA is right, less dust and weaker trade winds could allow the Atlantic’s worst hurricanes to grow even more destructive.

But if there’s more dust, as Jenkins’ and Gueye’s preliminary work suggests, some of those storms could lose their punch. Lives and billions of dollars in property hang in the balance.

You could see the stakes play out last summer, when the Saharan Air Layer grew especially dense. In Charleston, the beginning of hurricane season is a time of warnings and pleas to prepare. Like humidity, anxiety settles in for the summer.

But beginning in June, the dust switched off South Carolina’s hurricane season. Then the dust cleared in September, and the switch flipped back on. The hurricane nursery off West Africa grew busier. Four cyclones soon formed, including Hurricane Ian, which sideswiped Charleston later that month before landing in Georgetown as a Category 1 storm.

Forecasters predict a “near normal” hurricane season in 2023, thanks in part to El Nino, a warming in the Pacific that tends to reduce hurricanes in the Atlantic. But the Sahara’s dust remains an unknown variable, a switch yet to be flipped.

•••

It’s this uncertainty that fuels Moussa Gueye’s search for answers. It’s why one morning in May he wanted to show the place that first incubated that quest.

After teaching a class, he drove out of Kaolack on a hot and dusty two-lane road. Along the way, he passed groves of baobab trees, plump but without leaves because it was still the dry season. He arrived in Mbour and walked the sandy streets of his old neighborhood.

The sun was bright and the skies clear. Not much dust in recent weeks, especially compared to last year. He walked to the beach where his uncle’s family used to live. Goats wandered between the pirogues as the surf washed toward the ruins of the house.

The night the waves came generated so many questions.

“Many years later, I had the answer: climate change,” he said.

Rising waters stole land and homes here, as these waves have done all along the West African coast. It can feel overwhelming, the rising seas, the rising temperatures, the accelerating pace of it all.

But there’s something we can do, he said, glancing toward the western horizon, toward the Atlantic hurricane nursery.

We can take more measurements, document more dust events. With this information, we can improve our computer models, he said. With more precise models, we’ll have better predictions about those forces of nature. We’ll have more time to adapt. Those waves of change? They won’t come as surprises in the night, he said. We’ll know they’re coming.

Borso Tall, a freelance journalist in Senegal, contributed to this report.

Acknowledgments and About the Story

Michael Kaplan, professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the Desert Research Institute in Nevada, provided important background and guidance, as did Joseph Prospero, professor emeritus at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School's Department of Atmospheric Sciences. Prospero was quick to note the early and under-recognized Saharan Air Layer discoveries of other scientists, such as Guillermo Luloaga of Venezuela and Christian Junge.

Jason Dunion, a researcher with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hurricane Research Division, also discussed his important dust transport work.

For this story, we traveled into Mauritania to set our eyes on the Sahara itself, a potentially perilous journey in a pirogue across the Senegal River to a country that doesn’t see many foreign journalists. Borso Tall, a journalist based in Senegal, was instrumental in making that happen, as well as acting as a French and Wolof translator for many of our interviews.

Senegal has had one of the most stable democracies in West Africa, but just before our visit and near the end, the country had deadly protests and riots. Add political instability to the already daunting number of hurdles West African scientists face in getting their research done and distributed.

Almamy Badiane, a guide and translator in Dakar, also helped us gain a deeper understanding of Senegalese culture.