GILGIT, Pakistan—On a July morning, Saqlain Abbas, 26 years old, stood before rows of students, Mandarin textbook in hand, while a Pakistani soldier sat silently at the back of the classroom with a gun at his side. Hanging on the wall was a collection of idyllic Chinese landscapes—the reddish-orange mountains of Gansu, the placid waters of a lake in Xinjiang. Here, at Karakoram International University, in a remote, rugged terrain that is still contested territory between India and Pakistan, the Pakistani military has been sponsoring free Mandarin courses for indigent students.

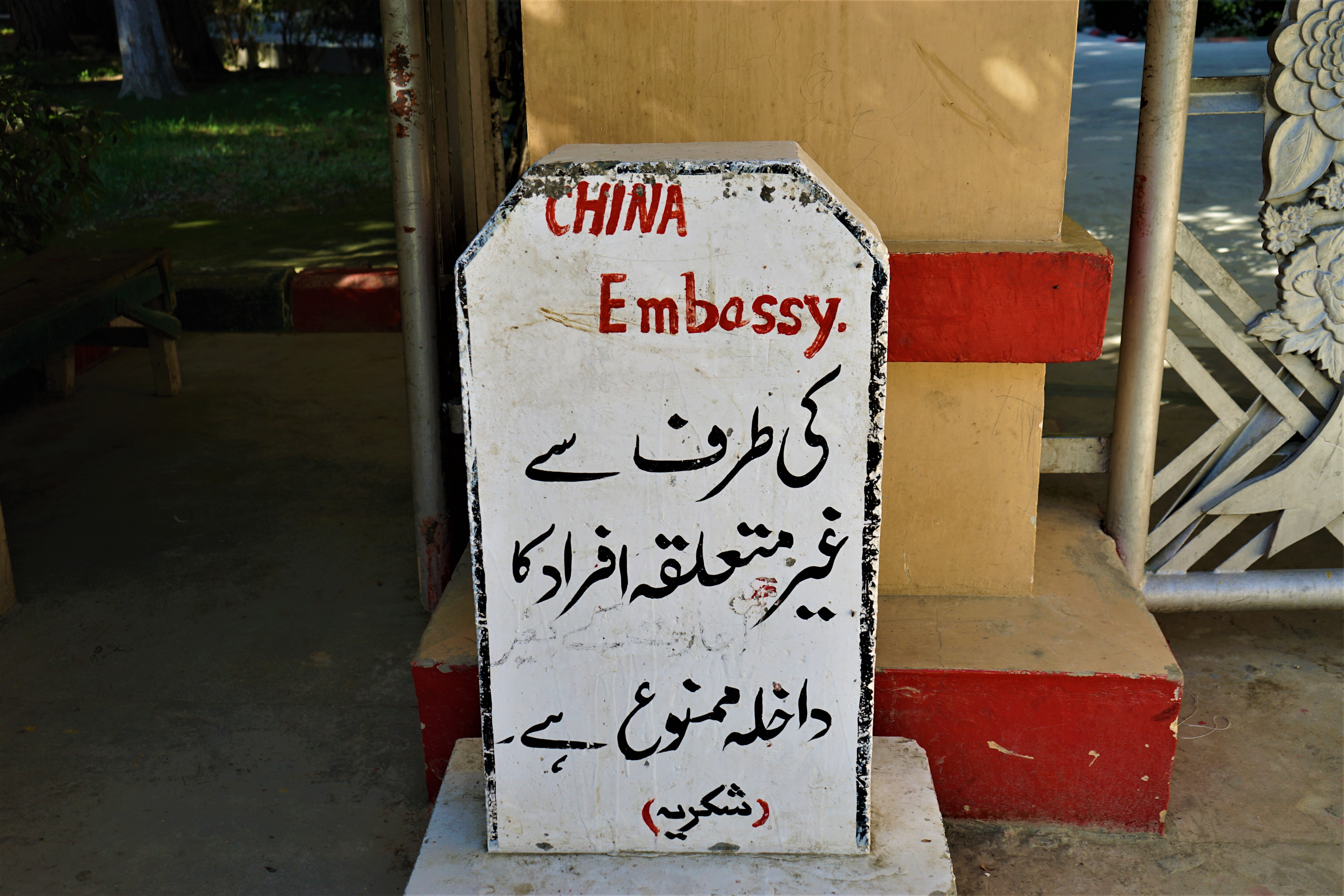

“Previously, students were more inclined toward English,” Muhammad Ilyas, the director for the university’s Institute of Professional Development, told me. Today, that’s changing, as young Pakistanis increasingly gravitate toward Mandarin in search of jobs and degrees. As part of an infrastructure development plan inked with Pakistan in 2013, China has pledged $60 billion to build what’s known as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)—a network of roads, pipelines, power plants, industrial parks, and a port along the Arabian sea. Intended to increase regional connectivity and trade between the two countries, CPEC is part of Beijing’s trillion-dollar Belt & Road Initiative (BRI). BRI aims to create land and maritime trade routes integrating 70-odd countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe, including politically turbulent states like Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

In many ways, CPEC is a bellwether for this broader global initiative. Prior to Prime Minister Imran Khan’s trip to China this month, the Chinese ambassador to Pakistan, Yao Jing, boasted that the program had already generated 75,000 jobs for Pakistanis. The Karachi-based Applied Economics Research Center and Pakistan’s Planning Commission say that in the next 15 years, 700,000 to 800,000 jobs may be created under CPEC, largely in the infrastructure, energy, and transportation sectors. It’s a hope the country desperately needs to pan out: As many as 40 percent of youth are unemployed, and Khan’s trip to Beijing hinged on the hope that the Chinese might inject more cash into Pakistan’s battered economy. The South Asian country is currently seeking a bailout package from the International Monetary Fund, an organization which previously said it will review the extent of Pakistan’s debt to Beijing.

On the ground, young Pakistanis are already investing in the language skills to capitalize on future job opportunities with the Chinese. “Chinese has become as important as English to learn,” Sherullah Baig, a student in Gilgit, told me. The military provided him free accommodation and tuition to attend three levels of Mandarin classes. Almost everyone in his course joined because of CPEC; Baig’s classmates are a mix of engineers, teachers, retired army officials, and fresh college graduates.

In the past, English was the sole language of upward mobility in Pakistan, both a relic of British colonial rule and a means of accessing Western markets, educational institutions, and jobs. Now, Mandarin has become the “hot new trend,” said Abbas, the Mandarin instructor in Gilgit.

In many countries along the BRI, China’s rising economic influence has provided it with an opportunity to exercise soft power through the dissemination of Chinese language and culture. In Thailand, Mandarin language education has seeped into universities, vocational institutes, the Royal Palace Secretariat, and even the immigration bureau. In Pakistan, the growth in Mandarin-language learning has been fueled by direct funding from the Chinese and Pakistani governments, as well as a mushrooming cottage industry of private teachers and institutes claiming to provide “the Chinese edge.”

In Pakistan, CPEC has been built upon historically high levels of partnership between the two nations. Both Pakistani and Chinese officials have characterized Sino-Pakistan ties as an “all-weather friendship” that’s “higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the ocean, and sweeter than honey.” In 2014, a Pew Research Center survey found that nearly 80 percent of Pakistani respondents had a favorable view of China—the highest public opinion rating of China in the world. While cultural and linguistic exchange have not traditionally been a centerpiece of the relationship, many young Pakistanis are now increasingly looking toward China for education and employment, necessitating learning Mandarin.

In May, Pakistan hosted the first CPEC Chinese Job Fair on Punjab University’s sprawling campus in Lahore, the country’s second-largest city. More than 30 Chinese businesses interviewed students for jobs as interpreters, tax assistants, and more. “CPEC has created enormous jobs,” Aisha Noor, a 25-year-old engineer waiting in line to submit her resume to a construction company, told me. Noor had completed a free Mandarin course sponsored by the Punjab government, and in front of her several Pakistanis were being interviewed in the language. “I would give the job to the person who speaks my language,” she said, as we watched another Pakistani student introduce himself to the company in Mandarin.

Pakistanis have long been aware of the differential opportunities afforded to a person based on language. Under British rule, the colonial administration was heavily reliant on native manpower, and English-language missionary schools became surprisingly popular—although their administrators were disappointed by a general lack of Christian converts. Today, the country’s education system is splintered along two parallel language tracks, English and Urdu. The languages lead to vastly different economic opportunities, with many students in Urdu-speaking classrooms feeling they suffer disadvantages in the job market. Fearing what might happen if China dominates the global economy, many Pakistanis are embracing Mandarin to have a head start in the so-called “Chinese Century,” said Rana Ahmad, the host director of the Confucius Institute at Punjab University.

Nonetheless, Pakistan’s extravagant borrowing from China has drawn some concern. China’s economic promises to Pakistan have not always come to fruition. Between 2001 and 2014, China pledged $135 billion to Pakistan, only 4 percent of which materialized, according to Eric Warner, an adjunct policy researcher at the RAND Corporation who has been tracking China’s foreign aid. Today China accounts for nearly half of Pakistan’s trade deficit, and Pakistan is among the countries most vulnerable to debt distress on China’s new Silk Road.

A lack of transparency regarding the terms of CPEC loans and investments still worries many Pakistanis, and some express skepticism about bullish job creation figures. “The jobs are an illusion,” Ahmad said. “People believe they can get a job, so maybe they should learn the Chinese language. And I always ask them, ‘If that’s so, why are there still unemployed Chinese? They have to first give jobs to themselves, and then they will give them to you.’”

Along the BRI, similar anxieties are playing out, with Malaysia recently pulling out of Chinese projects, citing fears that repaying the loans could plunge Malaysia into bankruptcy and leave it perilously indebted to the Chinese government. In Sri Lanka, a failure to pay Chinese loans spurred the Chinese government to seize Hambantota Port under a 99-year lease last year. In August, in its annual report to Congress, the U.S. Department of Defense warned that BRI might simply turn into a tool for advancing China’s own political or military agenda: “Countries participating in BRI could develop economic dependence on Chinese capital, which China could leverage to achieve its interests.”

Still, Ahmad is optimistic that China’s deals with Pakistan will receive more transparency and review under the tenure of Prime Minister Imran Khan, who previously called for placing CPEC’s financial details before parliament. His party’s election manifesto said it was imperative for domestic industries and laborers to benefit from CPEC as much as Chinese businesses, even saying that China should work toward knowledge transfer to allow Pakistani businesses to thrive on their own soil. “If the Chinese are thinking they can dictate anything to Pakistan with respect to CPEC, they are living in a fool’s paradise,” Ahmad told me.

Today, over 30,000 Chinese work in Pakistan, and Chinese companies have had to contend with the cultural challenges of operating in a new milieu, including Pakistani requests for religious accommodation.

Some Pakistanis also question why the onus to learn a new language falls on them, rather than the Chinese. However, the Confucius Institute’s Ahmad understands why the Chinese are not rushing to learn local languages. “They don’t need us,” he said. “If you find anything in the market, it says ‘Made in China.’ That means our markets need Chinese goods, not that their markets need Pakistani goods.”

The exchange has not been entirely one-sided, however; China has also offered scholarships and other benefits to young Pakistanis. “Students are going where they can easily advance their education and seize economic opportunities,” Abbas said. While the U.S. and Europe may loom large as attractive destinations, obtaining visas is difficult even if one learns the language. China, on the other hand, is making itself open to young Pakistanis by offering scholarships and jobs.

In 2016, Abbas himself received a scholarship to spend two years at the Beijing Language and Culture University in China. On the streets of Beijing, he was struck by the city’s development and the diversity of the students, some of whom were also on scholarships. As his Mandarin improved, Abbas was excited to engage locals in conversation. However, when he told young Beijingers where he was from, he was taken aback by how little they knew about Pakistan. From their childhoods, Pakistanis are taught about their ironclad friendship with China, he told me. “The friendship is very strong.” On the other hand, he said, the youth in Beijing have a dim awareness of China’s role in Pakistan. “They don’t even know a country exists called Pakistan.”