Anna Filipova photographs areas that most of us will never set foot in. But she’s not just a photographer, she’s also a researcher. These two disciplines dovetail for Filipova in her specialty, focusing on environmental topics in remote and often inaccessible areas. Previously, In Sight published Filipova’s work in the coal mines in Svalbard, Norway, between continental Norway and the North Pole.

Recently, Filipova set out to document how climate change is affecting a small town in far north Greenland. Filipova told In Sight about her latest project. The following text has been edited for clarity.

“Qaanaaq, in North Greenland, is the world’s northernmost naturally inhabited town, with 656 citizens. It was built in the 1950s, without consideration of climate change, which make Qaanaaq very vulnerable and one of the most affected towns in Greenland by climate change. Many of the locals in Qaanaaq live in permafrost areas, and their homes and other key infrastructures, such as roads and bridges, are built on frozen ground. As the permafrost thaws, the ground becomes weaker and less able to support these structures. This can cause buildings to collapse, roads and pipelines to fail and moisture to seep inside houses, creating unhealthy living conditions. Inhabitants resort to taping the cracks in their homes [to deal with] adverse conditions.

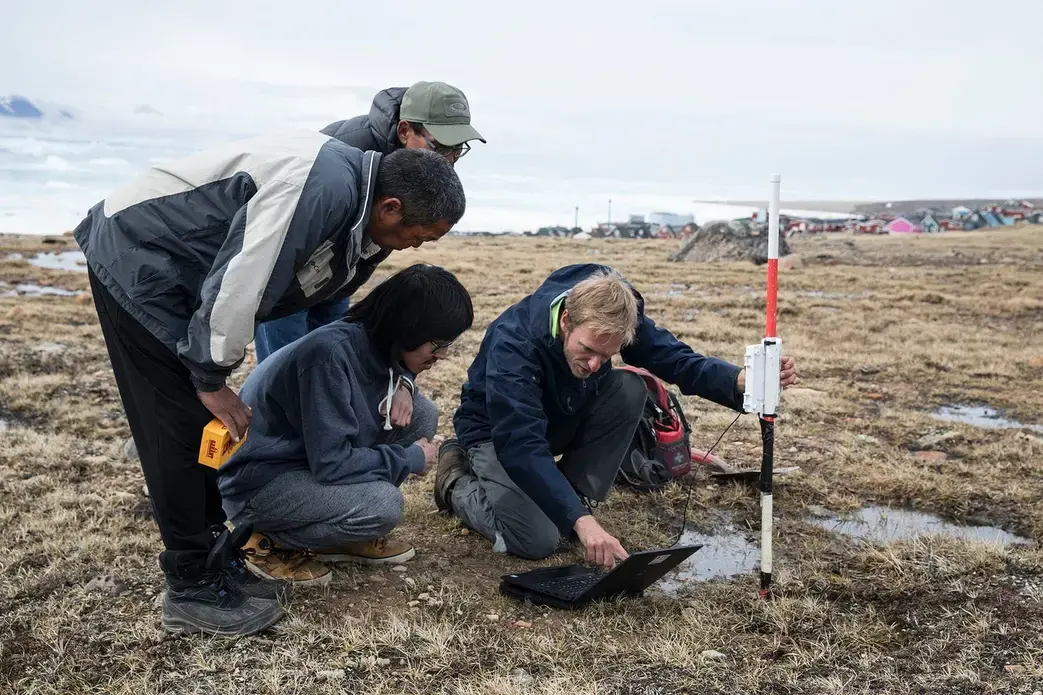

Sebastian Zastruzny has been studying permafrost in the region for the last few years and says that “part of Qaanaaq is built on finer material [clay, silt and sand], which is frost-susceptible. This means that the soil is moving up and down when it freezes, as ice forms a structural part of the soil. If this soil thaws and the foundation of the house does not go deep enough/is wrongly constructed the house begins to sink.” This is what is happening in Qaanaaq.

Qaanaaq is one of the last towns in Greenland that survives predominantly from hunting. In this part of the world delivery of goods happens only twice a year, once when the ice breakes in June and again before the sea ice forms in September. Each year the hunting season gets shorter because of unstable conditions on the sea ice, as climate change disrupts long-held hunting traditions [patterns] and travel routes. Some local hunters say that things are changing by the year and they “can’t be sure of anything.”

During the summer months, residents get their water from a nearby river; however, in winter it is simply too cold for the river to flow. Icebergs from the sea ice are collected and mounted on trucks [and] brought to a special facility where the ice is melted and connected and distributed to all houses in Qaanaaq by a water tanker. As the sea ice starts to break in spring and the conditions become increasingly uncertain and perilous, the simple task of collecting fresh water becomes [more] dangerous. Locals say that the price of water is so expensive that even diesel is less costly.

The Qaanaaq community has a long history of pride, self-reliance and self-sufficiency which has been sustained through generations via hunting and cultural practices. For many, living according to these customary ways of being is an expression of cultural identity, and this identity is at risk of corrosion alongside the shift in climate change.”

You can see more of Filipova’s work on her website, here and follow her on Twitter @Anna_Filip.