GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — One shows the prisoner nude and strapped to a crude gurney, his entire body clenched as he is waterboarded by an unseen interrogator. Another shows him with his wrists cuffed to bars so high above his head he is forced on to his tiptoes, with a long wound stitched on his left leg and a howl emerging from his open mouth. Yet another depicts a captor smacking his head against a wall.

They are sketches drawn in captivity by the Guantánamo Bay prisoner known as Abu Zubaydah, self-portraits of the torture he was subjected to during the four years he was held in secret prisons by the C.I.A.

Published here for the first time, they are gritty and highly personal depictions that put flesh, bones and emotion on what until now had sometimes been portrayed in popular culture in sanitized or inaccurate ways: the so-called enhanced interrogations techniques used by the United States in secret overseas prisons during a feverish pursuit of Al Qaeda after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

In each illustration, Mr. Zubaydah — the first person to be subject to the interrogation program approved by President George W. Bush’s administration — portrays the particular techniques as he says they were used on him at a C.I.A. black site in Thailand in August 2002.

They demonstrate how, more than a decade after the Obama administration outlawed the program — and then went on to partly declassify a Senate study that found the C.I.A. lied about both its effectiveness and its brutality — the final chapter of the black sites has yet to be written.

Mr. Zubaydah, 48, drew them this year at Guantánamo for inclusion in a 61-page report, “How America Tortures,” by his lawyer, Mark P. Denbeaux, a professor at the Seton Hall University School of Law in Newark, and some of Mr. Denbeaux’s students.

The report uses firsthand accounts, internal Bush administration memos, prisoners’ memories and the 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report to analyze the interrogation program. The program was initially set up for Mr. Zubaydah, who was mistakenly believed to be a top Qaeda lieutenant.

He was captured in a gun battle in Faisalabad, Pakistan, in March 2002, gravely injured, including a bad wound to his left thigh, and was sent to the C.I.A.’s overseas prison network.

After an internal debate over whether Mr. Zubaydah was forthcoming to F.BI. interrogators, the agency hired two C.I.A. contract psychologists to create the now-outlawed program that would use violence, isolation and sleep deprivation on more than 100 men in secret sites, some described as dungeons, staffed by secret guards and medical officers.

Descriptions of the methods began leaking out more than a decade ago, occasionally in wrenching detail but sometimes with little more than stick-figure depictions of what prisoners went through.

But these newly released drawings depict specific C.I.A. techniques that were approved, described and categorized in memos prepared in 2002 by the Bush administration, and capture the perspective of the person being tortured, Mr. Zubaydah, a Palestinian whose real name is Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn.

He was the first person known to be waterboarded by the C.I.A. — he endured it 83 times — and was the first person known to be crammed into a small confinement box as part of what the Seton Hall study called “a constantly rotating barrage” of methods meant to break what interrogators believed was his resistance.

Subsequent intelligence analysis showed that while Mr. Zubaydah was a jihadist, he had no advance knowledge about the 9/11 attacks, nor was he a member of Al Qaeda.

He has never been charged with a crime, and documents released through the courts show that military prosecutors have no plans to do so.

He is held at the base’s most secretive prison, Camp 7, where he drew these sketches not as artwork, whose release from Guantánamo is now forbidden, but as legal material that was reviewed and cleared — with one redaction — for inclusion in the study. Other drawings he has done of himself during his imprisonment were published last year by ProPublica.

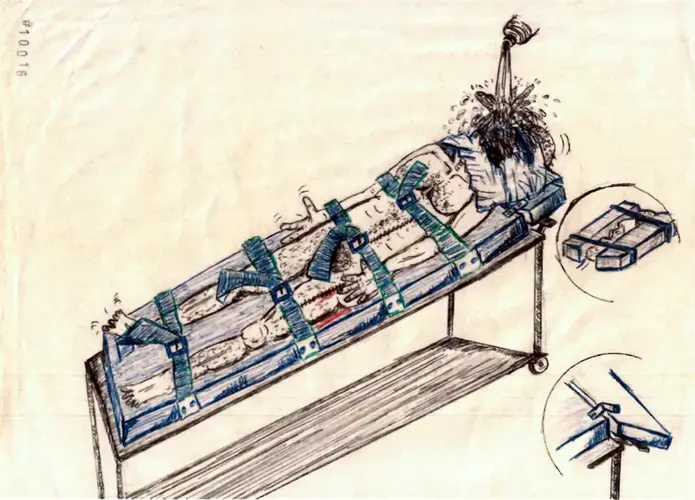

Waterboarding

In this drawing, the prisoner portrays himself as nude on the waterboard, immobilized as water pours down on his hooded head, his right foot contorted in pain. The image contrasts with some others seen in popular culture; an exhibit at the Spy Museum in Washington, for example, shows a guard pouring water onto the face of a prisoner who is neatly clad in what looks like a prison jumpsuit.

Mr. Zubaydah’s self-portrait also shows a design detail not present in most depictions — a drop-down hinge to tilt the prisoner’s head. Restraints hold down his wounded thigh.

The Senate Intelligence Committee study of the C.I.A. program concluded that waterboarding and other techniques were “brutal and far worse than the C.I.A. represented.” Its use induced convulsions, vomiting and left Mr. Zubaydah “completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth.”

In a now declassified account he provided his lawyer in 2008, Mr. Zubaydah described the first of what would be 83 waterboarding sessions this way: “They kept pouring water and concentrating on my nose and my mouth until I really felt I was drowning and my chest was just about to explode from the lack of oxygen.”

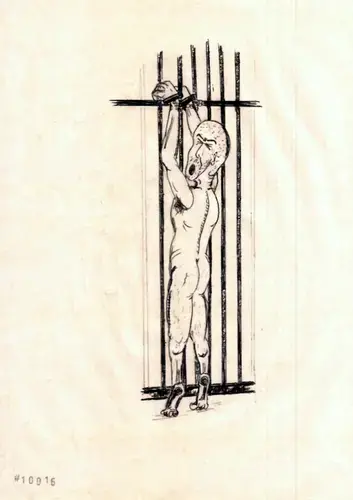

Stress Positions

Accounts by detainees in different black sites have differed on how this method was used. In his illustration, Mr. Zubaydah shows himself nude and shackled at the wrists to a bar above his head, forced to stand on tiptoe.

In his account, as reported by his lawyers, he was still recovering from what the C.I.A. had described as a large wound in his thigh, and he tried to balance his weight on the other leg.

“Long hours went by while I was standing in that position,” he told his lawyers. “My hands were tight to the upper bars.”

Some guards, he said, “noticed the color of my hands,” moved him to a chair “and the interrogation vertigo resumed — the cold, the hunger, the little sleep and the intense vomiting, which I didn’t know whether it was caused by the cold, the ‘Ensure’ or the noise.” (The C.I.A. put its prisoners on liquid diets in its program of so-called learned helplessness.)

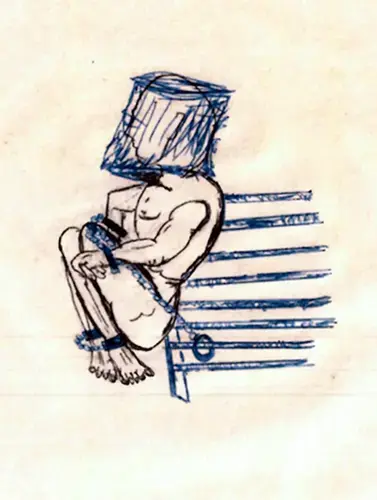

Short Shackling

Mr. Zubaydah, who is not known to have formal art training, drew himself in a hood, shackled in the fetal position and tethered by a chain to a cell bar to constrict his movement. In granting the C.I.A. approval to use a technique similar to this, Jay S. Bybee, a former assistant attorney general, noted in an 18-page memo dated Aug. 1, 2002, that “through observing Zubaydah in captivity, you have noted that he appears to be quite flexible despite his wound.”

He also noted in the authorization, addressed to the C.I.A.’s acting general counsel at the time, John A. Rizzo, that the agency asserted that “these positions are not designed to produce the pain associated with contortions or twisting of the body.”

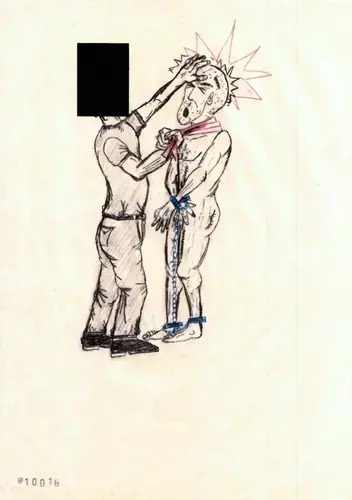

Walling

This image emerged from Guantánamo with a black redaction box over Mr. Zubaydah’s depiction of the face of his interrogator.

It shows the prisoner’s captor tightly winding a towel around his neck as he smashes the back of his head against what Mr. Zubaydah recalled was a wooden wall covering a cement wall.

“He kept banging me against the wall,” he said of the experience, which he described as leaving him blind “for a few instants.” With each bang, he said, he would fall to the floor, be dragged by the plastic-tape-wrapped towel “which caused bleeding in my neck,” and then receive a slap on his face.

In a 2017 deposition as part of a lawsuit that was eventually settled, James E. Mitchell, a former C.I.A. contract psychologist who devised the techniques with a colleague, John Bruce Jessen, said walling was “discombobulating” and meant to stir up a prisoner’s inner ears. “If it’s painful, you’re doing it wrong,” he said.

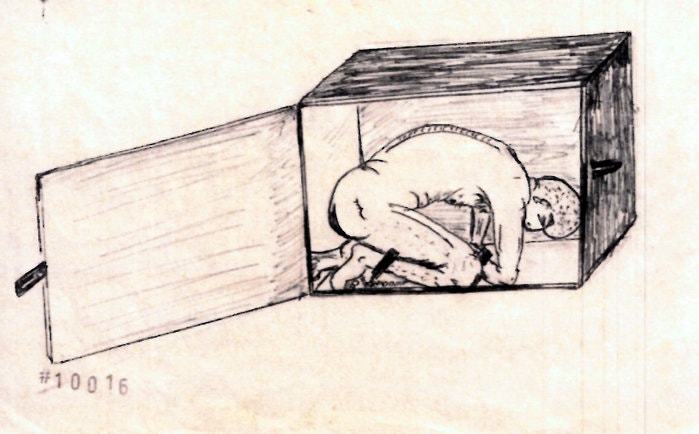

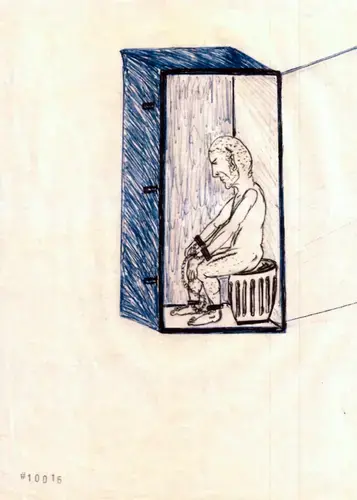

Large Confinement Box

In this drawing, Mr. Zubaydah is shaved, nude, shackled in such a way he cannot stand up and, by his account, is sitting on a bucket meant to serve as a toilet.

“I found myself in total darkness,” he said. “The only spot I could sit in was on top of the bucket, for the place was very tight.”

In his account, Mr. Zubaydah describes being confined in “a large wooden box that looked like a wooden casket.” The first time he saw it, guards were turning it vertical and a man in black clothes and a military jacket announced, “From now on, this is going to be your home.”

Mr. Zubaydah portrays himself in the drawings with both eyes. A photograph of him early during his time at Guantánamo shows him wearing an eye patch after the removal of an injured eye.

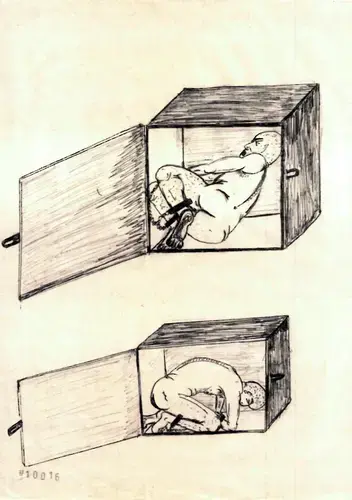

Small Confinment Box

The small box is similar to the one on display at the Spy Museum where, during a visit, children could be seen crawling inside.

In his account, included in the Seton Hall report, Mr. Zubaydah describes his time in what he called “the dog box” as “so painful.” He adds: “As soon as they locked me up inside the box, I tried my best to sit up, but in vain, for the box was too short. I tried to take a curled position but to no vain, for it was too tight.” He was immobilized and shackled in the fetal position, as he described it, for “countless hours,” experiencing muscle contractions.

“The very strong pain,” he said, “made me scream unconsciously.”

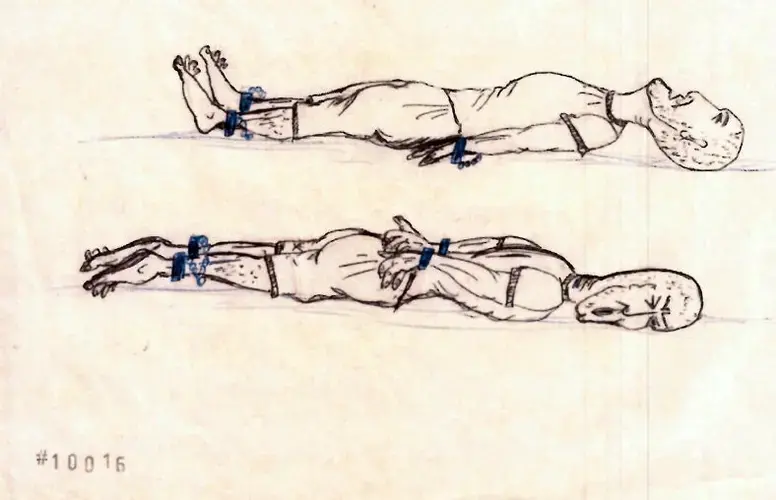

Sleep Deprivation

Mr. Zubaydah recalled that agents used a method of “horizontal sleep deprivation” that involved shackling him flat on the ground in such a painful position that it made it impossible to sleep.

The C.I.A. justified sleep deprivation by saying it “focuses the detainee’s attention on his current situation rather than ideological goals.” In approving this and other techniques in August 2002, Mr. Bybee said the C.I.A. had said it would not deprive Mr. Zubaydah of sleep for “more than 11 days at a time.”

In the Seton Hall study, Mr. Zubaydah recounted being deprived of sleep for “maybe two or three weeks or even more.”

“It felt like an eternity,” he added, “to the point that I found myself falling asleep despite the water being thrown at me by the guard.”

In this drawing, the prisoner portrays himself as lightly clothed.