Water quality concerns in rural Florida leave some families with groundwater wells dependent on bottled water in one of the most water-rich parts of the United States.

Samantha Kimmel and her husband bought their home in Suwannee County with the dream of creating a homestead. Unlike many other locals, they aren’t trying to farm for a living. But Kimmel’s eyes light up when she talks about her plans: Gardens full of food and cows grazing behind her home. Chickens and hogs and self-sufficiency.

Though their 10-acre homestead is in its early stages, the Kimmels’ dream is beginning to materialize. Two bay horses graze in the field next to the driveway. Sweet Tea is the aptly named Southern belle; she loves everyone. Lucky is a wild mustang, only about a year and a half old.

With just over 1,000 farms, Suwannee County has the charm of a small, close-knit community. Each town is the type of place where many people know each other’s names, their stories, some of them going back seven or more generations. Outside Live Oak — the county seat — old brick buildings sit tucked between new and restored ones, some crumbling on the side of the highway, history half-gone and full of wild-grown foliage.

Just blocks away in historic downtown, colorful signs and shops invite tourists who pile into parks like Ichetucknee Springs, Wes Skiles Peacock Springs and Suwannee Springs. Visitors and locals alike rent kayaks and paddleboards to float and revel in the crystal-clear water.

As a nonprofit journalism organization, we depend on your support to fund our nationwide Connected Coastlines climate reporting. Donate any amount today to become a Pulitzer Center Champion and receive exclusive benefits!

But for some rural residents of Suwannee and nearby counties, the water that makes up the area’s famed springs and rivers is also a source of concern. In a region known for its natural water, some families that rely on private wells are living out of bottles and jugs, filtered pitchers and faucets.

Kimmel and her family settled in Suwannee County a little over a year ago, after roaming the country in an RV. When the pandemic and changes to their work life made traveling less accessible, she and her husband decided it was time to start building their homestead.

Three years on the road in a 42-foot home brought the Kimmels close together. Samantha teaches environmental science online through Florida Virtual School, and her husband, Chad, works from home as an education program coordinator for an online high school. Their three children attend school virtually, too — all of them working from different computers under a shared roof.

When they first toured their new home, it checked all the boxes. They wanted a fixer-upper, something with land and potential. The Kimmels paid for “normal home inspections,” made sure the hurricane tie-downs met legal requirements and had the roof looked over. They were told then the well was only two years old, only to later find out it wasn’t — just the pump was. Still, Samantha ran the faucet to check the water. At the time, it ran clear.

But the home sat for a while during renovations. When they visited, the water would run brown.

Samantha started to do laundry, piling the family’s clothes into the machine only to be startled by brown sludge. They sent their water for testing soon after.

The sample tested positive for total coliform, a category of bacteria present in the digestive tracts of animals, including humans. Although it could be harmless, it could also signal that their water contains E. coli or disease-causing pathogens.

One year after that positive test, the Kimmels got used to living off bottled water. As an environmental science teacher, Kimmel said she dreads buying the single-use plastic.

“We’re looking into different things we can do instead,” she said, “But [there’s still] that bacteria. We need such precise filtration… And then we’re bathing in it, you know? We’re cooking with it.”

In urban areas, utilities such as those run by the cities of Live Oak or Gainesville manage the public water supply, treating water to meet federal standards for drinking. Dirt and dissolved particles are filtered out, then the water is disinfected to kill parasites, bacteria, viruses and germs.

But about 15% of people nationwide, often in rural areas, rely on private or “domestic” wells for drinking water, which is not regulated or tested by government. These homeowners are responsible for testing their own water, and some have no idea they may have to shell out thousands of dollars to deal with the results.

In a study including over 2,100 domestic wells, the U.S. Geological Survey concluded that one out of about five of them contained at least one contaminant “at a concentration greater than a human-health benchmark for drinking water.”

The Kimmels aren’t the only ones in the area who have struggled with water quality. Michael “Mike” Roth and his wife, Cindy Noel, lived in Suwannee County for nearly 12 years. Like many families along the river, their whole life revolved around water.

Recently, they lost trust in it.

When their water quality became visibly poor, Noel stopped drinking it. She and Roth both noticed it was turning brown. Roth believed plant life discolored the water, and he drank from the tap anyway. He quickly became ill.

“[I didn’t think it was] necessarily toxic,” Roth said. “Then last year, I got sick. And I felt like an idiot because I’d been drinking that water.”

The couple would routinely test their private well water to make sure it was safe. Eventually, the water started testing positive for bacteria. But even before then, Noel was concerned with how nearby agriculture and livestock would affect her water.

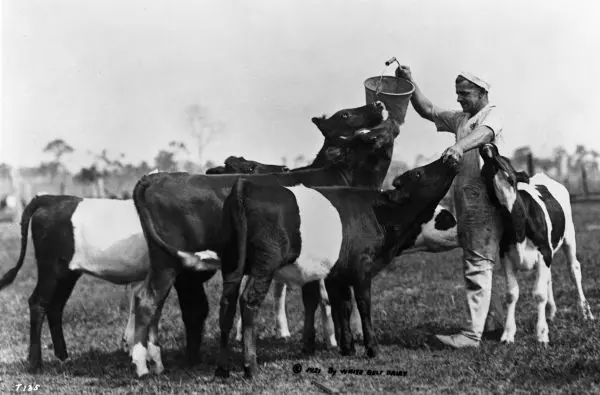

Cows and crops

In neighboring Gilchrist County, metal nozzles spray brown water — a mix of water and manure — across rolling, green fields. The smell of the natural fertilizer bleeds into clean air, causing locals to roll up their car windows. The nutrient pollution can end up in the Floridan Aquifer, the groundwater that flows through it and the springs bubbling up from it. It can make its way into private wells and people’s homes — even in bottles.

One of the most common contaminants found in private groundwater wells in the USGS study was nitrate, associated in rural areas with sources including fertilizers, cow manure, animal-feeding operations and leaky septic tanks. This pollution can wash from farms into local waterways, ultimately making its way into the aquifer. Then, the groundwater is pumped up by private wells, flowing to people’s homes and faucets, then into glasses and pots and bathtubs. If locals aren’t getting their water tested regularly, they may have no idea.

“You can’t smell it or taste [nitrate contamination],” said Bob Knight, director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute. “It’s invisible, and it’s a poison.”

Knight came to Gainesville as a college student and began studying the springs in 1979 with the pioneering ecologist H.T. Odum, one of the first scientists to document the structure and function of Florida springs ecosystems. After watching the blue pools decline for decades, Knight founded the non-profit Springs Institute in 2010 to research threats and solutions and educate the public.

In 2018, the institute released a report on the impact of a dairy in Suwannee on the Floridan Aquifer and nearby springs. Mainly, the report focused on privately owned Troop Spring in Gilchrist County.

Just a mile and a half from Roth and Noel’s home, Troop Spring sits tucked between trees and houses fronting the Santa Fe River. Knight said his research shows that Alliance Branford (formerly American) Dairy has affected groundwater, “moving beneath these dairies [toward] the Santa Fe River and springs in [the] area.”

Alliance Dairy cites sustainability and modern agricultural practices on its website — including efficient irrigation techniques and rotating crops for better nutrient management. Alliance employees did not respond to several requests for an interview or tour earlier this year.

The Springs Institute report also found Troop spring contains nitrate concentrations “well above” both the state of Florida’s spring nutrient limit of 0.35 milligrams per liter and the federal drinking water criteria of 10 milligrams per liter, or 10 mg/L. When monitoring the spring from 2016 to 2018, the nitrate levels consistently tested between 43 and 61 mg/L, an average of 151 times the legal limit for springs.

The federal government set the 10 mg/L limit for nitrate in drinking water in 1992 to protect against what is known as “blue baby syndrome” in infants. The condition occurs when ingesting a high concentration of nitrate leads to oxygen deprivation in a child’s blood, and it can be fatal if left untreated.

Recent epidemiological research suggests the legal limit may not reflect what is safe for public consumption. Studies have found nitrate exposure via drinking water can lead to thyroid cancers and thyroid disease, birth defects and early-term labor — even from water sources below the federal limit.

Nitrates are associated with many types of agricultural runoff, including dairies. Some dairy farmers use brown water in place of chemical fertilizers, citing the reuse of waste as sustainable agriculture. Large metal sprinklers span across the farms’ acreage, spraying the mixture of water and repurposed manure across green fields. But for every ton of manure produced by dairy cows, about 10 pounds of nitrogen can be introduced into the soil.

Locals pass these farms daily, enjoying the sights of historic rural Florida. But the beauty of these farms — with hundred-year-old oak trees and grazing calves — can be soured by the overabundance of manure. Even if passersby adjust to the smell, it’s piled up on farms out near the road. Thousands of pounds of waste sit waiting to be repurposed as fertilizer, composting or simply baking in the sun under a tattered plastic tarp.

But agriculture is a crucial piece of rural Florida. Statewide, agriculture brought over $7.6 billion into Florida’s economy in 2019. In Suwannee, the most recent agricultural census reported that 79% of the county’s farming revenue comes from livestock and associated products including dairy. Dairy operations have shifted to the region especially as development pushed the industry out of urbanizing areas. T.G. Lee, the historic Florida dairy founded in Orlando in 1925, now works with North Florida farmers such as Trenton-based Alliance Dairies Group.

The statewide industry also shifted in the 1980s, an era of bitter complaints that nutrients were damaging freshwater habitats in South Florida, including Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades. After a state buyout plan in 1986, 32 of the region’s 51 dairies left the area, many of them shutting down for good. Farms that wanted to stay were required to partner with the state to implement more environmentally sound practices.

“If you didn’t do that, basically, you could exit the industry,” said Ray Hodge, executive director of United Dairy Farmers of Florida. “And many farms did … The vast majority of them closed and didn’t get back into the area.”

Losing dairies means losing small businesses, farming families and livelihoods.

Consumers pay more for food and milk products shipped longer distances. But as much as dairies are an asset to the economy, water advocates point out that tourism has grown much bigger, contributing nearly $97 billion to the state’s economy in 2019 alone.

Noel, who lives near Alliance Branford Dairy and Troop Springs, is one of many locals who are hyper-aware of how thousands of cows and their manure might harm local water. Her experience has made her an activist for clean water. In 2017, she was arrested while protesting the Sabal Trail pipeline, a 517-mile interstate natural gas pipeline that now runs through Florida, Georgia and Alabama.

Even then, she said, people were concerned about the dairies.

“Two girls didn’t fit in the paddy wagon with us,” Noel said. “So, they got to ride in a car with another cop… Every time they passed a dairy, [he told them,] ‘that’s what you should be protesting.’”

When best practices aren’t good enough

To protect the fragile Floridan Aquifer from agricultural runoff, the state of Florida relies on “best management practices” for farms, overseen by the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The techniques are intended to manage the amount of nutrients ending up in the soil and groundwater.

“We have a challenging context here,” said UF soil scientist Gabriel Maltais-Landry, who teaches sustainable nutrient management. Weather conditions including heavy rainfall and sandy soils leave Florida vulnerable to nutrient leaching, he said, especially when it comes to nitrogen.

The rainfall — notorious and worsening in Florida due to climate change — drives an estimated third of nitrogen runoff, according to research.

Maltais-Landry also said “maybe 40 to 50 percent” of the nitrogen we apply to crops in the US reaches the actual product. For Florida, it’s a system that’s “almost inherently inefficient.”

Hodge, with the United Dairy Farmers, has lived in rural Florida his entire life. As a lobbyist for the dairy industry and a seventh generation Floridian, he understands the unique challenges the state faces when it comes to nitrate management.

“You can do everything right,” said Hodge. “You can… put your fertilizers out perfect. You’re following your [best management practices] … You do everything right, but you’re in Florida — you can’t control the weather.”

Another problem is that the best practices essentially rely on an honor system. Farmers in the Sunshine State operate under the “presumption of compliance,” meaning regulators trust them to implement these practices. Once they sign a statement of intent, farmers get credit for agreeing to reduce pollution. They are not, however, required to produce hard data to show they did so.

Lawmakers, environmentalists and farmers here and across the state butt heads on a lot of issues, but they do agree on this: Even if best practices are perfectly executed, they’re not a catch-all. Data from the Springs Institute shows that, even as farms like Alliance employ best management practices and practice sustainable agriculture, springs and groundwater are still suffering. And some lawmakers are more committed to protecting industry than to protecting water.

Merrillee Malwitz-Jipson, who owns a home and business in neighboring Columbia County, has probably spent more time in front of lawmakers and water managers than behind her cash register at Rum 138, her outfitter on the Santa Fe River. She and her husband moved to the area roughly 20 years ago when they bought property on the river with the intention of passing on a love for nature to their children.

Shortly after moving in, Malwitz-Jipson saw a contractor walking along the riverbank, spraying clouds of an unknown chemical.

“Don’t look at me,” he told her. “Go to the DEP.”

That was her first-ever call to the Department of Environmental Protection. Since then, she estimates she’s made hundreds.

But Malwitz-Jipson’s activism goes far beyond phone calls. It takes more than that to advocate for clean water. She organizes protests and events, circulates petitions and literature, and works to bridge gaps between farmers and environmentalists. She also educates her customers, which she considers a crucial role for water-based tourism businesses in Florida.

Visitors pile into the Rum 138 van in flip-flops, swim shorts or wetsuits, ready to kayak or paddleboard on the river. Malwitz-Jipson takes a detour, guiding them through her neck of the woods. En route to the river, she passes the dairies and the local hot spots, offering names and stories and science while the van bounces along unpaved county roads.

“They don’t come expecting an education,” she said. “They get one anyway.”

Yet in her years of Florida activism, Malwitz-Jipson has never had a clear-cut victory. The losses that sting the most are the ones in front of legislators and water managers, where leaders who could make change look her in the eye before signing off on a new pipeline, another bottled-water permit, fewer trees.

Recently, water advocates worry about a new law the Legislature passed this spring. The statute now allows citrus growers to apply fertilizer above the maximum rates recommended by industry professionals, including UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. If they hire a “certified crop advisor” to authorize the new amounts of fertilizer, the farmers’ practices will continue to fall under the presumption of compliance.

The law also requires UF IFAS to analyze site-specific nutrient management for crops other than citrus and develop research plans and recommendations for nutrient management. IFAS will also be required to submit an annual report to lawmakers.

But, over the next four years, citrus growers will essentially be free of any restriction of the amount of fertilizer they can apply, according to executive director of the Florida Springs Council Ryan Smart.

“The law sets a dangerous precedent,” said Smart. “[It] would have disastrous water quality impacts if applied to all Florida agriculture.”

Governor Ron DeSantis signed the bill into law in June.

Knight said the answer is not less regulation for agriculture, but more accountability for corporations. He believes part of the answer is limits on agriculture atop the most vulnerable parts of the Floridan Aquifer, including cutting down on the number of cows per farm. He and other environmentalists agree that, ideally, Florida should be managing what ends up in the water before it enters the soil instead of managing the pollution after the fact.

“All these things are solvable,” Knight said. “A few people — corporations – are creating the majority of the problem.”

Stewardship and solutions

In California, Huntington Farms grows produce including head and leaf lettuce, carrots, strawberries and celery on nearly 5,000 acres of land. At one point, the nitrate levels on the property were testing high. Manager Mark Mason said he had a few reasons for wanting to fix the issue.

First, he said he wanted to prioritize being a steward of the land.

“[Realizing] there is a better way to do things than what’s been done over years in the past,” he said, “that’s a big motivator.”

Mason also believes regulation is coming, and he wanted to be ahead of the curve to keep the farm running smoothly. But one of his biggest incentives has always been the consumer.

Though he doesn’t often hear it from the stores buying Huntington’s produce, Mason noticed a trend toward consumers demanding more ethically sourced food — including products that cause less harm to their environment.

A big part of this is managing nitrate levels, for which Huntington Farms uses a high-tech management strategy called precision agriculture. An app tracks water consumption, waste, nutrient loading in the soil and crop cycles to optimize the way Mason and his team water and otherwise tend to their crops.

But Mason knows precision agriculture isn’t necessarily a solution for smaller farms. Even though the app is free, farmers earning smaller margins may not be able to afford the extra staffing. He also said, for farmers, overapplication of water and fertilizer is essentially “insurance.” It’s a huge risk for smaller farming operations to change anything about their growing when they rely on maximum yields to pay the bills. And the average farm size in Suwannee is 47 acres. In Gilchrist, 146.

In Florida, private soil and water engineer Adelbert “Del” Bottcher says given the unknowns surrounding best management practices, high-tech solutions will likely be part of the answer to nutrient reduction in both urban and agricultural areas of Florida. The options include artificial wetlands; methane digesters that could use waste to generate biogas; chemical-treatment systems; vermiculture systems that use worms to break down organic solids; and shallow “interceptor” wells that treat nitrate-laden water before it is returned to the aquifer.

But technological solutions can be costly. And unless such solutions are required or subsidized, environmentalists and farmers agree they won’t likely be used.

Knight said the state’s Department of Environmental Protection has a responsibility to enforce surface water and groundwater nitrate standards. But regulators fail to do so, he said, and the responsibility is left up to individuals to police what comes up from the ground and out through their faucets.

When the Kimmels first discovered dangerous bacteria in the well on their dream homestead up near Live Oak, the family used bottled water to wet their toothbrushes. The kids, all under the age of 10 at the time, struggled to conserve while doing so — but they knew better than to use the tap water.

Now, they are using water from the tap again. The privilege comes with a new routine.

“Don’t wet your toothbrush first,” their mother taught them. “Then rinse it in the sink. And don’t use your toothbrush until it’s completely dry.”

“So far,” she said, “We haven’t gotten sick.”

The toothbrush victory is a small one. But families like the Kimmels are spending $50-plus a month on bottled water, hundreds of dollars to test their water, and potentially $1,000 to $8,000 for whole-house filtration systems. It’s not easy, especially for residents in an area where the median income is just over $23,000.

Last month, the Kimmels sent a sample of their water for additional testing. The coliform bacteria are gone, and they have no idea why. Samantha Kimmel believes the issue may reoccur seasonally, since they hadn’t changed anything or treated their water. For now, they plan to install a UV filter for about $800.

“We’re in a position where we can take care of this problem,” Kimmel said. “I just feel for the people who can’t… There’s a lot of people around here that just have to deal with what they have.”