Turkey has welcomed half a million Syrian refugees, but some Turks fear the newcomers may be putting a strain on Turkey's infrastructure and economy.

It's Syrian coffee that Husain Hamdawi and his wife, Jumara Hajirabi, can't live without. They fled Syria with their two children four months ago, leaving their apartment and most of their possessions behind.

But when friends or family visit from Syria, they ask for ground coffee.

They moved to Gaziantep, a city in southern Turkey where so many Syrians have moved recently that people have started calling it "Little Aleppo." Aleppo, Syria's commercial capital was barely two hours away by car before the war, and many of the Syrians who have come to Gaziantep are from that area.

Although they have reconnected with many old friends from Syria, their lives are completely different from before.

"In my kitchen in Aleppo," Hajirabi said, "there was a table and chairs and a TV. That kitchen was like a small house."

The kitchen in their current apartment—which had been built as student housing—is really more like a kitchen corner. It has a cabinet and a sink. The refrigerator is the size of a hotel mini-bar and the stove is a two burner hotplate squeezed onto a bit of counter.

Hamdawi and his wife share the apartment's one bedroom. The children sleep on twin beds in one corner of the living room. They both fell asleep on the couch while we were talking late one evening. I asked if I should go so they could sleep, but their mother said they'd gotten used to sleeping with the lights on, and grown-ups talking—even though they had their own rooms in Syria.

In Syria, their apartment was air-conditioned; here a fan whirs endlessly in front of the open window. The big, 3-D TV they had—Hamdawi loves new technology—has been replaced by a small old-fashioned one.

Still, they feel safe in Turkey, where there are no bombs, no snipers and no random arrests. Their daughter, Lama, is in second grade at a special school for Syrian refugees. Her favorite subject is English—she pulled out her English notebook and read the exercises to me.

Their son, Assad, who just turned two—he was born a few weeks before the uprising began—is a typical toddler, jumping on the couch endlessly, stopping only to admire himself in a video on his father's cell phone.

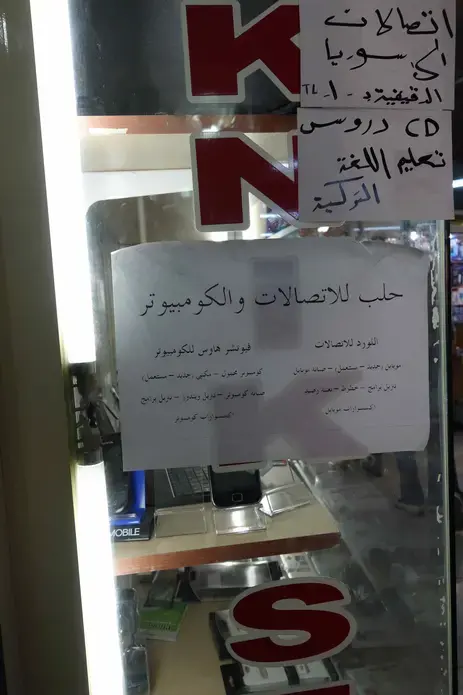

Hamdawi's professional life has been down-sized too. In Syria, he owned two businesses: a sleek computer and TV store, and a pharmaceutical distribution company. A few weeks ago, he and a Syrian friend opened a tiny shop in downtown Gaziantep, where they sell computers and cell phones to a mostly Syrian clientele.

But unlike his big shop in Syria, where he had people working for him, he and his partner do all the work themselves:

"It's like when we first started our businesses in Syria," he said, "when we had small shops and had to fix customers' cell phones and laptops ourselves. We haven't had to do that for years."

Hamdawi says he and his wife are operating on a five year plan; he's already talking about expanding his new business.

But he's also terrified Turkey could change its mind, and ask them to leave. He and his wife would like to go home, eventually, but they know it will be years before that can happen, if it ever does.

"Even if the Syrian regime goes soon," he said, "the Syrian crisis won't."