This story is second in a three-part series supported by the Pulitzer Center about how southwest Louisiana is recovering from Hurricanes Laura and Delta amid the pandemic. Read the first story here.

This story was published with The Hechinger Report.

Every weekday morning, Dr. Lisa Morgan wakes up at 3:45 a.m. at her cousin’s house in Lafayette, La., where she has been staying since Hurricanes Laura and Delta dealt a double blow to her Lake Charles home. The first storm tore a hole in the roof. “You could look up and see the sky,” she said. Mold started to grow on the walls, and then the second storm let more water in.

She drives over an hour each way to teach world history at LaGrange High School in Lake Charles. Her temperature is taken when she arrives, and then she heads to her classroom. She turns on gospel music — a ritual she’s had since she began teaching 28 years ago — and sanitizes all surfaces. When her first class comes through the door, Morgan takes their temperatures and seats them at numbered desks that will allow for easy contact-tracing if a student contracts COVID-19.

Morgan, who has a petite stature and a commanding voice, is over 50 and has underlying health conditions. She worries about being exposed to COVID-19, especially as cases rise across the nation, including in the Calcasieu Parish school system.

The dual crises of the coronavirus pandemic and a highly active hurricane season — five storms hit Louisiana this year — have made Lake Charles teachers’ jobs even more challenging. Every campus in the parish school district sustained damage; internet access has been spotty at best. Many students and teachers are still displaced, living with relatives or in hotels paid for by the state. Residents say the federal government has been slow to respond, and with so much rental housing destroyed, housing options are limited.

When LaGrange opened up for its first day of in-person teaching on October 29 — after a spring of virtual learning due to the pandemic and a delayed fall semester because of the hurricane — a small fraction of its 1100 students attended. The low number was partly because schedules were staggered to allow for social distancing, but hundreds could not make it to campus or opted to continue virtual learning.

“Our numbers are still low in every school,” said Calcasieu Parish School Board superintendent Karl Bruchhaus, in late November. “Some of them, just because those kids are online; some of them, because they’re not back. And we just need more time to figure out which are which.”

Morgan said that many of her students, who are predominantly Black, are scattered across Louisiana and Texas. She’s transparent with them about the struggles they’re facing together. “I wanted to share with them what I was going through, because I didn’t want them to feel that they were alone in that situation,” she said.

As climate change fuels more intense rainfall, hurricanes, and wildfires, the stress teachers and students experience will become more common. But most schools lack funding or capacity for adequate counseling services for students and staff.

“In many ways, teachers are frontline mental health workers,” said Betty Lai, a psychology professor at Boston College who researches the mental health impacts of natural disasters on children. In surveying students after disasters, Lai said she generally finds that up to half report post-traumatic stress symptoms. Depression and anxiety symptoms are also common. And the mental health impacts last: Lai said she has found them as far out as four years later.

When Louisiana schools shut down due to COVID-19 in mid-March, Calcasieu Parish teachers scrambled to transition to online learning. “Everybody sort of struggled through trying to develop a combination of paper packets and online instruction,” said Bruchhaus, the superintendent.

Students faced barriers to virtual learning. “Especially in our rural areas, they didn’t have good internet service at all,” said Teri Johnson, president of the Calcasieu Federation of Teachers and School Employees, a teachers’ union.

About 10% of students had no internet connectivity before the storms, according to Holly Holland, a spokesperson for the parish school board, though they lack specific data on which students. In the spring, the district deployed mobile hotspots to help bridge the gap, but more recently, “internet outages because of the hurricanes have made data collection difficult,” she said.

Despite high numbers of cases, the parish school board planned for in-person instruction for the 2020-2021 school year: All pre-K through sixth graders in person; seventh through 12th graders on staggered days. All students had a virtual option.

Morgan was nervous. She’d lost sorority sisters and church members, as well as a close childhood friend, to COVID-19. But she was also excited to see her students. “I believe in face-to-face-teaching,” she said. “I just don’t feel the internet takes the place of a teacher.”

The first day, parish officials recommended a voluntary evacuation for Hurricane Laura. “We never actually started school,” said Bruchhaus. The storm caused widespread power outages and major damage; all district schools closed for a month. A handful reopened in late September and early October, only to shut down days later when Hurricane Delta hit. Bruchhaus said damage from both storms has cost the district an estimated $300 million in rebuilding efforts.

The school board is conserving its budget because of all the unknowns remaining with storms and COVID-19, Holland said, adding that more funding could help with devices and connectivity issues.

Prolonged school closures of any kind result in significant learning losses for students. It’s still difficult to know how much progress students across the country lost as a result of school closures due to the pandemic, partly because state tests were canceled. Some researchers project that students began this school year having lost nearly a third of a year in reading and half of a year in math; others predict that by next fall, students may have lost three months to a year of learning.

“Those losses are tending to be more pronounced for children of color, or children living in poverty, than for white children or children living in greater privilege,” said Katherine Prince, vice president of strategic foresight at KnowledgeWorks, a national education policy organization.

There is also a significant social and emotional toll, especially when students are experiencing trauma. “A lot of children rely on their time in a school building for relative stability, for food, for a relatively safe environment,” Prince said. “The kind of social support fabric that schools provide has been opened up.” Holland, from the school board, said a district program provides weekly meals for students enrolled in virtual learning, and will offer meals to all families during the holiday break.

After Thanksgiving, the parish schools switched to in-person learning, though a virtual option is still available. For weeks, the school board has been debating how to make up lost days. In November, they decided to eliminate break days around holidays, and this month, they amended the calendar again, giving back holiday time but adding minutes to class time to make up some of the difference. The plan has yet to be approved by the state.

With few resources at their disposal, teachers are trying to bring back a sense of stability. Morgan has a background in social work and encourages her students to open up to her. “They want that normalcy back. I can see that in their eyes,” she said. “I want that normalcy back for them, too.”

As FEMA aid trickles in slowly, and insurance companies delay payments — many people in southwest Louisiana say aid came faster after Hurricane Rita 15 years ago — teachers face a mountain of logistical hurdles. Many are scheduling meetings with contractors or insurance adjusters for their damaged homes around school hours. An unknown number are commuting from other towns, due in part to the low number of rentals in Lake Charles.

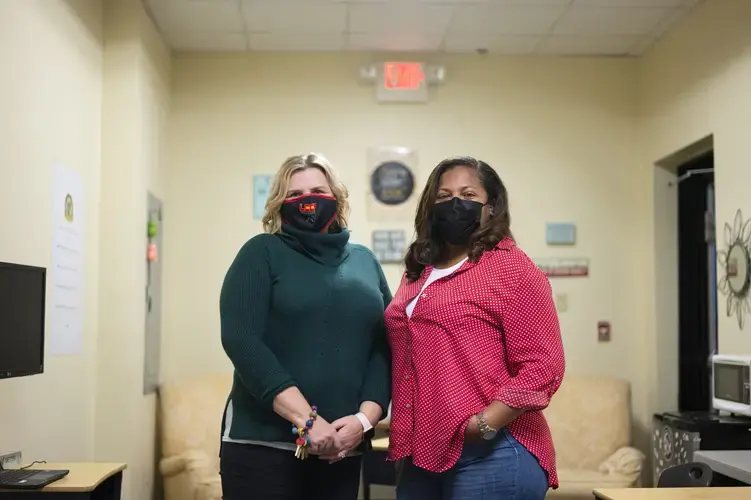

The district offers school employees three free sessions at Solutions Counseling, a mental health service provider in Lake Charles. Despite Hurricane Laura destroying its office, Solutions was offering tele-health services a week after the storm, according to office manager Destini Doucet. She said they are seeing a higher volume of teachers than normal.

The parish also put out a “Keep Calm Line” to connect residents with mental health resources. “Most everybody that I’ve talked to has made that phone call,” Johnson said. “Just to talk to somebody. Because they’re so weary, and they know that their friends and family are weary also. So they need to talk to somebody who maybe isn’t as weary.”

Johnson said at least 150 of her 1300 union members have left since June: “They’ve retired, they’ve had enough, they’ve quit teaching, or they’ve moved.” Morgan, who is a union representative, said other teachers have told her they could use more time to get their lives back on track.

Tiffany Guillory was a student at McNeese State University in Lake Charles when Hurricane Rita hit in 2005. She didn’t have the wherewithal to complete all her classes that fall; dropping one put her back a semester. Now a middle school technology teacher at S.P. Arnett, a public school in nearby Westlake, she can relate to her students. “They’re behind,” she said. “And you can’t do anything about it.”

Trauma from natural disasters can make concentrating and learning more difficult, contributing to lower standardized test scores. A study of North Carolina schools impacted by Hurricane Floyd in 1999 found that scores were lowered by 5% to 15%. Students often still have to take tests that determine whether they can advance to the next grade, even after missing days or weeks of school.

In the U.S., testing and grading systems often lack flexibility for these situations, said Prince, from KnowledgeWorks. “The pandemic and other disruptions, such as climate-related ones like Lake Charles has been experiencing, underscores the need that many in the education field have been advocating for for some time now: to shift our foundational approach to understanding student achievement to be mastery-based,” she said. That means using more personal evaluations of competency in different subject areas for students, especially in times of crisis.

Kelly Hawkins, an English teacher at the charter school Lake Charles College Prep (LCCP), has a difficult time figuring out how her students are faring through a computer screen. “It’s quite hard to do what I feel like is my purpose in molding minds and in having some type of positive effect, so that they will want to learn for the rest of their lives,” she said. Many of her students “haven’t been able to log on at all,” she said in October. Several lost their homes and were living with family in other states; others were in town, but lacked internet. The school resumed in-person classes after Thanksgiving.

Mental health coursework is generally not a requirement for teacher licensure, yet teachers are often the first people outside the home to encounter a child experiencing trauma after a disaster. “We are depending a lot on teachers who have not been trained to really respond to children’s mental health needs,” Lai said.

School counselors are supposed to be one of the stopgaps. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students to each school counselor, but only two states meet that mark. Louisiana averaged 441 students per counselor during the 2018-2019 school year.

LCCP’s behavior interventionist, Pam Strobel, is working with staff to locate displaced students and offer them counseling. “Situational depression has really taken a toll on students and families,” she said. More students than usual have reached out to her after the hurricanes, which she believes is in part because of the anonymity of virtual school. “It’s really not cool, especially in high school, to go to the counselor,” she said. Some students text her personal phone; other times, she visits parents and students in their driveway if there are issues among family members.

Teachers have been reaching out to Strobel, too. “They’re displaced, but they’re still teaching, and they’re still doing their best to stay connected and stay positive,” she said. “I don’t know how they do that, day in and day out.”

Guillory, the middle school teacher, wakes up an hour earlier to exercise and ground herself before work. “There’s times I have to slow myself down because I have trouble remembering things, just kind of from the trauma of, you know, seeing what happened to your town,” she said.

School districts across the U.S. are struggling during the pandemic, and have asked Congress for more funding. According to Holland, from the Calcasieu Parish school board, funding from the state will be determined in the spring of 2021 based on student counts on Feb. 1 — meaning that if many are still displaced and not showing up, schools could receive less money.

Every school system, especially in places vulnerable to climate-driven emergencies, needs adequate funding for counselors, Lai said. “Helping students understand how to deal with and cope with extreme stress is really important,” she said, “and the people in schools who are positioned to know how to help children prepare in advance are school counselors.”

Usually, this time of year, Morgan would stay after school to work the concession stand at basketball games. Now, though, she hits the road back to Lafayette when she’s done teaching. Her vision is bad at night, so she likes to get home before dark. “It really makes me sad,” she said. “I really want to be there. And I just can’t because housing is not here.”

Morgan grew up attending Calcasieu Parish public schools. When she returned home to care for her elderly father a few years ago, she “fell in love with Lake Charles all over again.” She, and many other teachers, want to stay there, serving their students. And they want to get adequate support from the parish, the state, and the nation to do so.

“We love where we are. And we love what we do. We love Calcasieu Parish,” she said. “But we want them to love us too. We want some love back.”